Featured Articles

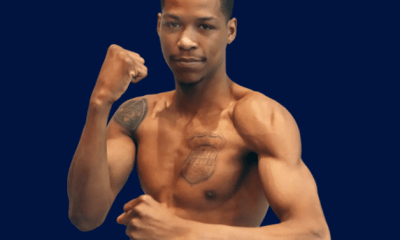

Art of Boxing Series: Paulie Ayala (Part Two)

It was like a duel between two Old West gunslingers as Paulie Ayala a little-known Texas southpaw stood poised to greet New Mexico’s Johnny Tapia, the mercurial world champion from Albuquerque.

When the bell rang that Las Vegas night on June 26, 1999, the tightly wound bantamweights delivered the most riveting battle of the year. Showtime will replay the 1999 Fight of the Year on Friday, April 17 as part of their “Rivalries” series.

Their battle proved so captivating they did it again a year later.

Ayala grew up in a town famous for producing world champions in the 1980s. And though his amateur career fell short, it allowed him to realize he could compete with the best. It also allowed him to sharpen his fighting style to hair-splitting accuracy that still goes unnoticed.

As a youth, he served as a sparring partner for world champions like Freddie Norwood and Stevie Cruz. Norwood would defeat Juan Manuel Marquez and Cruz would hang a loss on Barry McGuigan. Those victories by his stablemates opened up his eyes to his own possibilities.

“Freddie Norwood beat Marquez. And to me he didn’t train 110 percent and to be able to do what he was able to do and fight the way he fought, he was really a goofy guy,” said Ayala thinking back on helping Norwood prepare for Marquez in 1999. “So, when he beat Marquez I wondered how long he trained for that. Probably nothing. He beat Juan Manuel Marquez; that’s crazy.”

Ayala toiled away sparring against some of the most talented fighters in the world in hopes of getting his own world title shot.

“I was never really concerned who I was going to fight because my sparring was better than anybody I was going to face at that point of my career until I fought for a title. I sparred Freddie Norwood, Robert Quiroga, and John Michael Johnson when he was getting ready for Junior Jones. I sparred a lot of top guys during that time,” said Ayala of his battles in Fort Worth. “Sparring in those days was like war every day.”

After three years of mowing down the competition, Ayala captured the NABF bantamweight title with a third-round knockout of Miguel Espinoza on March 1995. He held it for more than three years, wondering when he would get a world title shot.

Yokohama, Japan and La Vida Loca

Sometimes when you lose you win. That proved true when Paulie Ayala arrived on the shores of Japan to challenge for the WBC bantamweight world title against Joichiro Tatsuyoshi.

Despite starting strong, an accidental clash of heads resulted in a technical decision loss after six rounds in front of 22,000 fans in Yokohama Arena on August 1998.

“I thought I was in control. He was a boxer and had a little charisma in his boxing and little flamboyance. In the first round I caught him and he buckled so I started boxing him and tried to see if I could catch him again. He had a little cut in his left eye so I started working on that, so the next thing you know I went to the body and we crashed heads. The referee deducted two points from me. They said I intentionally did it. It ended in the sixth round,” said Ayala. “It was one of my biggest disappointments because I wanted that green belt.”

After waiting six years to get a world title opportunity he worried that another might not come around for another six years. He was wrong.

“I immediately went back to the gym when I got home and took a couple of quick fights. And next thing you know I got a phone call from Top Rank and they said we got another title shot for you. This time it’s in the states and that’s when it was with Johnny Tapia,” said Ayala. “To me, I know they accepted the fight because my fight in Japan was not televised here. So, no one got to see it. That’s why I thought I even got that opportunity anyway. They didn’t see the fight. They just know I went to fight for the world title and I lost. I think it was a blessing in disguise.”

Tapia was undefeated and perhaps the most charismatic bantamweight in the history of prizefighting. His “Mi Vida Loca” tattoo said all you needed to know about his lifestyle but fans loved the bad boy from Albuquerque who spent several years in jail. When he returned to boxing his popularity soared once again.

In 1994 Tapia won the WBO super flyweight world title by knockout against Henry Martinez and held on to it for 11 title defenses. Then on July 1997 he engaged in a battle to unify the super flyweight division against crosstown rival Danny Romero who held the IBF version. Tapia won the bloody rivalry by unanimous decision after 12 rounds in Las Vegas.

After two more defenses of the WBO and IBF super flyweight titles, Tapia moved up a weight division and captured the WBA bantamweight world title by majority decision over Nana Yaw Konadu in Atlantic City. After one more fight Tapia was ready to defend the bantamweight title and Ayala was the chosen opponent.

“He was a super popular guy,” said Ayala. “Definitely I was the underdog. I was going to take the back seat. Johnny Tapia was the fan favorite, media favorite, I mean everybody loved him.”

The first press conference took place in Beverly Hills, California and the media showed up in full force at the Friars Club on Santa Monica Boulevard. Tapia was surrounded by reporters with cameras, microphones and handheld recording devices.

Near the entrance to the Friars Club sitting on a metal chair next to his trainer was Ayala who calmly watched the media frenzy around Tapia. It was the only time Tapia would enjoy dominance.

“When you start the press conferences and the press tours everything is cordial. Then there is camp and you come back and it’s time to fight. When we first saw each other at the first press conference, we made eye contact and I could see, not concern but he knew I was focused,” said Ayala.

Mandalay Bay

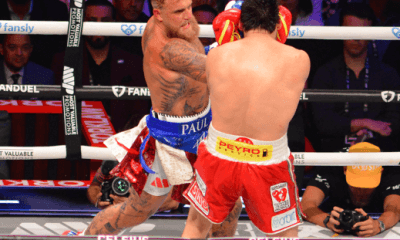

Just three months earlier the Mandalay Bay Resort and Casino had opened its doors for the first time. As a boxing venue, it was still brand new when Paulie Ayala and Johnny Tapia met for the WBA bantamweight title on June 26, 1999.

It would soon become home to a bevy of epic prize fights starting with the bantamweight clash. There’s a particular reason why casinos in Las Vegas love boxing. It has a seductive allure to gamblers, real sports fans and boxing fanatics.

Prizefighters are a different breed.

Outside of a boxing ring many prizefighters are congenial, and eager to talk to fans and media. But once the weigh-ins take place their faces and demeanor change drastically like Jekyll and Hyde.

“I feel that’s another part of the fight, It’s a mental fight,” Ayala said about the drama involved at weigh-ins and pre-fight press conferences days before the fight.

When the two bantamweights stepped in the middle of the ring to hear instructions Tapia was hyper and eager to unload. Ayala quickly noticed as referee Joe Cortez gave his instructions.

“I could see in his eyes he had a totally different demeanor. His eyes were like gone. He was into the fight. I already knew he was angry. And to me, that’s better. The more angry he is the less he is going to listen to Freddie (Roach),” said Ayala remembering their face-to-face moment seconds before the fight. “He kept looking at me (during instructions) and he kind of jumped to the side and I jumped to the side. But I didn’t know he was going to come and push me.”

Tapia shoved Ayala seconds before the actual fight.

“Joe Cortez said specifically to me ‘Paulie if you do anything and don’t let me do my job I’m going to disqualify you.’ And I already lost my first world title (bid) I wasn’t going to risk something stupid to lose the fight like that again,” said Ayala.

Tapia was an excellent boxer and could be difficult to hit. But his main weakness was his machismo inside the boxing ring. Ayala figured it out quickly.

“I kept catching him, I would kind of go whew! Every time I hit him with a good shot I’d go whew. And he hated that,” said Ayala explaining that the verbal taunts set off Tapia to engage more. “The main thing is I got him out of his fight game for one, of course Freddie Roach was trying to get him to box, and turn, then counter. But he wasn’t listening.”

Suddenly the tactical skirmish turned into an all-out war. Neither was willing to move backward and the two 118-pounders were blasting each other relentlessly daring each other to match power shots. It was exciting stuff for the fans who roared and reacted every time a big blow landed.

Early on Ayala thought Tapia was tiring. But he was mistaken.

“I thought he was already tired the way Johnny would suck up all the air after a round. So, I thought it was already downhill for him. So, we’re getting into the 10th round he is still doing the same thing. But his work ethic in the later rounds was even more intense. So, I was like ‘man, this is what championship boxing is all about,’” Ayala said.

Ayala was in his element as Tapia attacked with his unrelenting assault. The Texas southpaw caught many of the blows off his gloves and slipped and countered with perfect timing. It was memorable stuff as the pair of pocket-sized destroyers traded bombs over 12 rounds.

“He was boxing good but he wasn’t landing any hard shots and I was landing way better shots than he was landing. That’s why he decided to stop boxing and moving and he decided to trade with me. I’m not saying he made it easier but he made it better, by far for me. Because I was having to cut off the ring and it was a lot more work than for him to just stay there in the pocket and we could just fight it out right there.”

It was the type of warfare that Ayala preferred: in-the-pocket exchanges. The kind he had perfected for years in Fort Worth sparring sessions against world champions.

When the final bell sounded Ayala slumped to the ground.

“Right when the bell rang to complete the final round I fell down in the middle of the ring, not only because of the excitement but I was exhausted. I used everything I had,” recalled Ayala.

Ayala knew he was not the favorite and Tapia had never been beaten. But he hoped the judges saw what he felt was his victory.

“All I was waiting for is when they said ‘and the new champion of the world!” That was an experience that I will never forget,” said Ayala who won by unanimous decision 116-113 twice and 115-114.

Bedlam ensued and some booed and others cheered. According to CompuBox, an unofficial group that tabulates punches for the television fans, Tapia landed more blows. But Ayala had a style that wasn’t easy to tabulate correctly.

All in all, it was a spectacular fight and one that would later be voted Fight of the Year by Ring Magazine. For the impressive win, Ayala was also selected Fighter of the Year in 1999 by the same publication. Think of it. He was voted over Oscar De La Hoya, Felix Trinidad, Roy Jones Jr. and Lennox Lewis.

Ayala was the last fighter to win that honor in the 20th century.

“That was the greatest feeling. Look at all the champions around. You had everybody. You had the Klitschkos, De La Hoya, Vargas, you had all these guys. Erik Morales, you had Johnny Tapia all these guys that are in the Hall of Fame. I beat all them for Fighter of the Year award. That was in 1999. I mean everybody was fighting. Floyd Mayweather, Manny Pacquiao those guys were all fighting back then too. People don’t take that into consideration. I was going against the top guys so for them to even consider me that was so awesome,” said Ayala.

Ayala in the 21st Century

Ayala and Tapia would fight again 16 months later but at the MGM Grand. Once again Ayala would defeat the New Mexican fighter but at a catchweight of 124 pounds. Just like their first encounter the pair of sluggers let the punches fly.

The Texas southpaw would defend the WBA title successfully three times then move up a weight division and defeat Clarence “Bones” Adams for the IBO super bantamweight title twice. And just like the Tapia clashes the wars with Adams proved scintillating too.

Ayala tried the featherweight division too and was denied by Erik Morales and Marco Antonio Barrera. He finally retired after the loss to Barrera in Los Angeles.

“In boxing you have to have that killer instinct. You are training for war. It’s not a sport where you are in there to win on points. You are in there to hurt that guy, to take his will,” said Ayala. “It doesn’t matter what a fighter says after the fight. Sometimes you know you took his soul.”

Ayala still lives in Fort Worth, Texas with his wife Letitia. They have two grown offspring and maintain a boxing gym called the University of Hard Knocks Gym. They provide classes for those suffering from Parkinson’s Disease called Punching Out Parkinsons. They also provide boxing therapy classes for At Risk, suicidal and autistic youth.

They have an Instagram account called Paulie Ayala’s UHK and can be found on Twitter.com too.

Don’t forget to watch Ayala vs. Tapia 1 and 2 on Showtime’s boxing series on Friday April 17.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

To comment in this story in The Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 330: Matchroom in New York plus the Latest on Canelo-Crawford

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoVito Mielnicki Jr Whitewashes Kamil Gardzielik Before the Home Folks in Newark

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap 329: Pacquiao is Back, Fabio in England and More

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoOpetaia and Nakatani Crush Overmatched Foes, Capping Off a Wild Boxing Weekend

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoCatching Up with Clay Moyle Who Talks About His Massive Collection of Boxing Books

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoFabio Wardley Comes from Behind to KO Justis Huni

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoMore Medals for Hawaii’s Patricio Family at the USA Boxing Summer Festival

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoDelving into ‘Hoopla’ with Notes on Books by George Plimpton and Joyce Carol Oates