Featured Articles

Avila Perspective, Chap. 94: Eddie “Animal” Lopez and the Power of Boxing

Most people around the world like boxing. It’s a fact that goes unnoticed by American newspapers and television outlets that cover sports, but not in other countries.

Team sports have the upper hand when it comes to media coverage. But the sweet science has its devout followers too.

Years ago I accidentally discovered that boxing, especially prizefighting, had a somewhat secret following even in UCLA’s prestigious halls of academic learning.

Back before the Internet was publicly known, newspapers were a primary source for information and several student newspapers provided me with opportunities to learn the craft of writing and news gathering.

As students we would gather inside the office reading major newspapers like the Los Angeles Herald-Examiner, looking for possible stories to adapt or follow up. On one particular day I came across a story that involved a heavyweight fighter named Eddie “the Animal” Lopez. He was quoted saying that he would fight Muhammad Ali for $1 dollar.

That caught my attention and when I mentioned it the others laughed. I asked the editor-in-chief of the La Gente newspaper if it would be OK to pursue the story. He thought it was a great idea and another writer asked to go with me.

We made some calls and found a day that we could drive to downtown Los Angeles to the historic Main Street Gym. It was during the early 1980s; it could have been 1980 when we walked into the second story gym with a camera in my hand and a note pad.

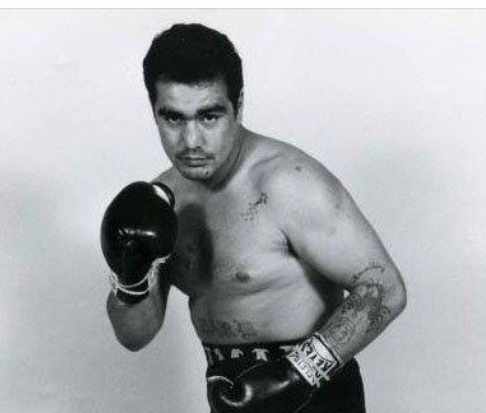

It wasn’t my first time visiting the gym but it had been years since I had been there. At the top of the stairs we were greeted, or to be more accurate, acknowledged by someone who asked for the person we were trying to find. After we told this person, he yelled out something and a few minutes later Eddie “The Animal” Lopez arrived like magic. He wasn’t a very tall heavyweight and you wouldn’t describe him as physically cut like Ken Norton. But his ability to work his way inside against taller fighters and his mental toughness were things you could not teach.

Lopez was a unique character. He was raised in East L.A. near the Ramona Projects and despite having a hard edge was one of the most affable prizefighters I ever met. He showed us around and was eager to introduce us to Alberto Davila who he called a great boxer. A few years later Davila would win the bantamweight world title.

We asked Lopez about his encounter with Ali at the Beverly Hills press conference and he was kind of impressed that we knew about it. He mentioned the name of the sportswriter who penned the story and said that he was looking for a fight and would love to fight the great Muhammad Ali.

After about 20 minutes of interviewing we asked permission to take photos of Lopez while training. The gym wasn’t really conducive for photographs but we managed to obtain a few decent photos.

One week after the interview we published the story in La Gente newspaper and it was circulated throughout the UCLA campus and in a few news stalls in the nearby areas like Santa Monica, West L.A. and Beverly Hills. We drove to the Main Street Gym and dropped off a few copies for the gym and Lopez.

Later that week we drove through the streets of East L.A. and dropped off more copies to various restaurants like Manuel’s El Tepeyac, Ciros, Andy’s Super Burger, Chronis and Troy’s Burgers. We made a habit of delivering newspapers to news stands on Whittier Boulevard in East L.A. My family lived about four blocks from Garfield High School in East L.A. It’s a school I attended for a semester before getting booted out.

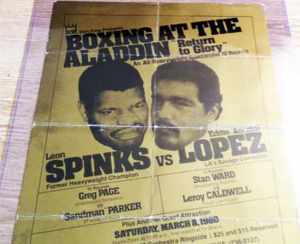

Lopez would soon fight former world champion Leon Spinks to a split draw after 10 back and forth rounds in a heavyweight fight at The Aladdin in Las Vegas. His last fight was against the very tough Tony Tucker in 1984 and he would lose by knockout in the ninth round. If you knew anything about Lopez it was that he could take a punch.

The rugged East L.A. heavyweight passed away nearly three years ago. I saw him one time after a fight at the Olympic Auditorium. He was a very popular fighter and fans loved him.

Power of Boxing

Students enjoyed the story and made me realize that boxing’s appeal was universal, even with university students. I kept that knowledge handy so when big fights emerged we invited fellow students to our large three-bedroom apartment in Palms near the MGM Studios in Culver City, California. We packed the apartment with students on the night that Thomas Hearns fought Sugar Ray Leonard on September 16, 1981.

The popularity of our fight party for UCLA students got me thinking the next time a big fight arrived – we could charge for admission. Not that we were making money for profit, but enough to buy pizza, beer, soda and rent a room at a nearby hotel that carried a new cable network HBO. Nobody at UCLA had HBO.

On November, 1982, the next mega fight arrived and matched two legendary fighters in the fearsome Aaron Pryor and Nicaragua’s Alexis Arguello. Their first encounter took place at the Orange Bowl in Miami, Florida.

As part of a UCLA Latino student newspaper La Gente we shared an office with the Afro-American student newspaper Nommo and became very close friends. When Pryor met Arguello it was a perfect opportunity to have another fight party and we organized a good one.

Of course most of the Latinos cheered for Arguello and most of the Black students cheered for Pryor and when it was over we all agreed we saw one heck of a fight. It would happen again 10 months later and we organized another party.

The memory of all of us students cheering and enjoying two great prize fights remains one of my fondest memories. Many of those students are still good friends of mine. We’ve lost a few over the years, but man, we had some good times.

Everywhere life would take me I discovered the power of boxing. When I took a part-time job at an outdoor news stand near Beverly Hills called Robertson News and Magazines on Robertson Avenue and Pico Boulevard, I met many customers there that shared my love for boxing. Some of the patrons were famous actors, musicians, dancers and writers and all had immense interest in prizefighting like Michael Jackson, Bubba Smith, Gene Simmons, Milton Berle and many others.

Strangely, because I was working at a news stand, I would glance through various newspapers from around the country. I noticed that almost all were void of boxing news. I remembered this information when I later was hired as a journalist for weekly throw-away newspapers and later still as a writer for daily newspapers. I would use this information much later when I pursued a career in journalism.

Fans

What Americans fail to realize – especially news media outlets – is the popularity of boxing worldwide. It’s an ignorance that has continued for three decades. But the arrival of streaming has made boxing’s universal appeal more obvious to even the most ignorant. Boxing will always be around even when team sports disappear.

Fans of boxing don’t wear t-shirts with emblems of their favorite fighters or display pennants in their bedroom. Some may have a photo or poster of their favorite fighter but the lack of boxing coverage keeps prizefighting in somewhat darkness. But then a big fight comes along and suddenly the mania begins.

Can the sport survive today with this pandemic? Will fans watch a prize fight that has no fans in the audience?

I would not bet against boxing.

Even though most gyms have closed, two boxing compounds remain functioning but keep outsiders from coming in. Abel Sanchez has the Summit Gym in Big Bear, California and despite only having two boxers in residence at the moment, they are both still training and ready to battle like Navy Seals.

Cecilia Braekhus the unified welterweight champion of the world has been in Big Bear since the beginning of the year. She has a tentative date against Chicago’s Jessica McCaskill who also remains in training.

In Riverside, several boxers remain on a training compound including Vergil Ortiz Jr. and WBC super lightweight titlist Jose Carlos Ramirez. Both stay and reside at the Robert Garcia Boxing Academy compound and have not stepped off the property. Both have kept training despite the lack of a fight date. But they are ready to go.

“We won’t really have a problem as all the guys are living, eating and training together so it’s not going to affect us too much. Jose Ramirez always wants to spar Vergil Ortiz, because he gets the best work from him,” said Robert Garcia to Matchroom Boxing’s Anthony Leaver.

But fighting without fans present has become an important factor to survive at the moment.

“Having millions of people watching on TV is just not the same as having the live crowd cheering your name, or against you which can motivate you, it’s something boxing needs but we’re going to have to deal with it and teach our fighters how to handle it,” Garcia said.

Most fans have never been to a live boxing event. When you consider this fact, you realize that boxing will continue to thrive, but not in the normal capacity for a short while. Still, watching on television or through streaming devices carries immense appeal.

For decades my huge family always gathered around for the big fights. Whether in East L.A., San Antonio, or even Las Vegas you know that other families look forward to boxing events. Today, any individual with a smart phone can watch live boxing at the click of an app.

It’s the power of boxing.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in The Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 330: Matchroom in New York plus the Latest on Canelo-Crawford

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoVito Mielnicki Jr Whitewashes Kamil Gardzielik Before the Home Folks in Newark

-

Featured Articles21 hours ago

Featured Articles21 hours agoResults and Recaps from New York Where Taylor Edged Serrano Once Again

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoCatching Up with Clay Moyle Who Talks About His Massive Collection of Boxing Books

-

Featured Articles5 days ago

Featured Articles5 days agoFrom a Sympathetic Figure to a Pariah: The Travails of Julio Cesar Chavez Jr

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoMore Medals for Hawaii’s Patricio Family at the USA Boxing Summer Festival

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoCatterall vs Eubank Ends Prematurely; Catterall Wins a Technical Decision

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRichardson Hitchins Batters and Stops George Kambosos at Madison Square Garden