Featured Articles

The KIMBALL CHRONICLES: Bidding Adieu to John Ruiz, The Quiet Man

A TSS CLASSIC: I wasn’t even in Atlantic City on the night of March 15, 1996. Mike Tyson was fighting Frank Bruno in Las Vegas the following evening, and Don King had dressed up the undercard with four other world title fights (plus Christy Martin-Dierdre Gogarty), so even though I worked for a Boston newspaper and Johnny Ruiz, who lived across the river in Chelsea, was one of ours, there was never any question in my mind where I should be that weekend.

But a bunch of us did get together to watch Friday night’s HBO show, a unique event the network’s then-vice president Lou DiBella had cooked up called “Night of the Young Heavyweights. Not many of the 16 guys who fought that night were especially well known then, though several of them would be later. There were heavyweights from six different countries, and while six of these unknowns would eventually fight for world titles, only two would actually win one – and they both lost that night. Shannon Briggs got stretched in three rounds by Darroll Wilson, and Ruiz was counted out by Tony Perez exactly nineteen seconds into his fight against David Tua.

It was about as devastating a one-punch knockout as you’ll ever see. Nobody, or at least nobody in Boston, was exactly gloating about it, but the long-range implications were obvious. Even though Ruiz and his manager Norman Stone were saying “he just got caught; it could have happened to anybody, anyone who’d spent much time around boxing could have told you that a knockout like this one usually turns out to be the first of many.”

As an amateur Ruiz had been the best light-heavyweight in New England, but never quite made it to the top in national competition. In the 1992 USA Boxing Championships he lost to Montell Griffin. In the Olympic Trials in Worcester that year he lost to Jeremy Williams. You wouldn’t term either loss a disgrace – those two met in the final of the Trials, which Williams won, but then Griffin came back to beat him twice in the Box-off and earned the trip to Barcelona – but it did sort of define Ruiz’ place in the amateur pecking order.

As a pro Ruiz had already lost twice. Both were split decisions (to the late Sergei Kobozev in ’92 and to Dannell Nicholson a year later) and controversial enough that Stone could scream “We wuz robbed!” on both occasions, but now they, coupled with the Tua result, appeared to have defined his place in the heavyweight picture as well.

* * *

Three months later at the Roxy in Boston, Ruiz TKO’d Doug Davis in six. Davis was 7-17-1 going into that one and lost 16 of the 17 fights he had afterward. Davis was a career Opponent from Allentown, Pa., a little guy built like a fireplug who lost to nearly every mid-level heavyweight of his era, so the only real significance to this one was that back then he usually tried very hard to finish on his feet so that he’d be available the next time the phone rang.

To watch Stoney’s reaction, you’d have thought Ruiz had just knocked out Lennox Lewis at the Roxy.

As soon as the main event was over, I’d glanced at my watch and realized there was an edition I could still make if I filed my story in the next 20 minutes. I was already pounding away at my laptop before the fighters cleared the ring.

Next thing I knew, a red-faced Norman Stone was directly above me, bent over and shouting through the ropes, which was about as close as he could come to getting in my face without falling out of the ring.

The invective consisted for the most part of a stream of disconnected expletives, but from the few decipherable words in between I gathered that he hadn’t much enjoyed my interpretation of what the Tua loss might portend for Ruiz’ future.

Since I was on deadline, I just ignored him and kept writing. Trainer Gabe LaMarca and Tony Cardinale, Ruiz’ lawyer, finally dragged him away.

Seated next to me was a young boxing writer named Michael Woods, now the editor of The Sweet Science.

“What, asked Woodsy, “was that all about?

“Nothing, I shrugged without looking up. “He’s just a f—— psychopath, is all.

I finished my story and filed it, and then raced to Ruiz’ dressing room. Stone was still there.

“I don’t come up in the corner and interrupt you between rounds,” I told him. “If you want to act like a jerk (though I don’t think ‘jerk’ was actually the word I used), fine, but don’t try and drag me into it when I’m working.”

Having gotten that off my chest, I added “Now. Is there something you want to talk about?”

Actually, there wasn’t. He’d just been blowing off steam. The point of the exercise had been to remind Ruiz that he was standing up for him.

But I’ll have to admit two things. One was that John Ruiz had 27 fights after the Tua debacle, and he didn’t get knocked out in any of them. (Even when he was stopped in what turned out to be the final bout of his career, it was Miguel Diaz’ white towel and not David Haye’s fists that ended it.)

The other is that if somebody had tried to tell me that night that John Ruiz would eventually fight for the heavyweight championship of the world, let alone do it dozen times, I’d have laughed in his face, so on that count maybe Stoney got the last laugh after all.

* * *

No boxer ever had a more loyal manager. Stone was a hard-drinking Vietnam veteran who eventually kicked the booze and replaced it with another obsession. He had enough faith in Ruiz’ future that he twice mortgaged his house to keep the boxer’s career afloat, and was so protective that he eventually convinced himself, if not Ruiz, that it was the two of them against the world.

At that point in his career Ruiz was still vaguely aligned with London-based Panix Promotions, the same people who were guiding the fortunes of Lewis. It is unclear exactly how beneficial this might have been to Ruiz, who between 1993 and 1996 flew across the ocean to knock out obscure opponents in some fairly obscure UK cards, other than giving him the opportunity to boast that he knocked out Julius Francis a good four years before Mike Tyson got paid a fortune to do the same thing.

Working with Panix’ other heavyweight client was also supposed to be part of the arrangement, but Ruiz’ actual time in the ring with Lewis was brief. Ask Stoney and he’ll say that Lennox wanted no part of him after “Johnny kicked his ass.” Ask Lewis and he’ll laugh and point out that sparring with Ruiz was pretty much a waste of time anyway unless you were getting ready to fight a circus bear.

In any case, a few fights later Cardinal and Stone made what turned out to be a pivotal career move by enlisting Ruiz under Don King’s banner. (Panos Eliades seemed utterly shocked that a fellow promoter would poach a fighter from under his nose. “Ruiz isn’t Don’s boxer, he’s my boxer,” exclaimed Eliades.)

If Cardinale and Stone get full marks for aligning Ruiz with King, matchmaker Bobby Goodman deserves credit for the next critical phase of Ruiz’ career.

In January of 1998 Ruiz fought former IBF champion Tony Tucker in Tampa, and stopped him in 11 rounds. For his next three outings, Goodman was able to deliver opponents who each had but a single loss on their records, and, moreover, to strategically place the bouts on high-profile cards which provided national exposure to The Quiet Man.

In September 1998, on the Holyfield-Vaughn Bean card at the Georgia Dome, Ruiz fought 19-1-1 Jerry Ballard and stopped him in four.

In March of ’99 on the Lewis-Holyfield I card at Madison Square Garden, he scored a fourth-round TKO over 21-1 Mario Crawley.

In June of ’99, on a Showtime telecast topped by two title bouts in an out-of-the-way Massachusetts venue, Ruiz was matched against 16-1 Fernely Feliz, and scored a 7th-round TKO.

Ruiz at this point had been working his way up the ladder of contenders, and by the time Lewis beat Holyfield in their rematch that November, Ruiz was now rated No 1 and the champion’s mandatory by both the WBC and WBA. Ruiz, who at that point hadn’t fought in five months while he waited for the title picture to sort itself out, needed to beat an opponent with a winning record to maintain his position.

Enter Thomas “Top Dawg Williams of South Carolina (20-6). Ruiz knocked him out a minute into the second round.

Was it on the level? Hey, I was ten feet away that night in Mississippi, and I couldn’t swear to it, but I can tell you this much: three months later Williams went to Denmark, where he was knocked out by Brian Nielsen, and then when Ruiz fought Holyfield at the Paris in Las Vegas in June of 2000, Williams and Richie Melito engaged in an in camera fight before the doors to the arena had even opened, with Melito scoring a first-round knockout that was the subject of whispers before it even happened.

Having cut a deal and been flipped into a cooperating witness, Williams’ agent Robert Mittleman later testified under oath that he had arranged for Top Dawg to throw both the Nielsen and Melito fights.

The government had extensively prepped its witness before putting him on the stand. If the Ruiz fight had been in the bag, isn’t it reasonable to suppose that Mittleman would have been asked about that, too?

In any case, when Lewis ducked the mandatory, the WBA vacated its championship and matched Ruiz and Holyfield for the title. Holyfield won a unanimous decision, but under circumstances so questionable that Cardinale successfully petitioned for a rematch.

The return bout, at the Mandalay Bay in March of ’01, produced Ruiz’ first championship, along with another career highlight moment. Like so many of the Quiet Man’s other highlights, this one also involved Stone.

Stone had been foaming at the mouth since the fourth, when a Holyfield head-butt had ripped open a cut to Ruiz’ forehead. Then, in the sixth, Holyfield felled Ruiz with what seemed to be a borderline low blow that left Ruiz rolling around on the canvas. Referee Joe Cortez called time, deducted a point from Holyfield, and gave Ruiz his allotted five minutes to recover.

No sooner had action resumed than Norman Stone, loudly enough to be heard in the cheap seats, shouted from the corner, “Hit him in the balls, Johnny!

So Johnny did. And at that moment, not only the fight and the championship, but the course John Ruiz’ life would take for the next ten years were immutably altered.

The punch caught Holyfield squarely in the protective cup. Holyfield howled in agony, but didn’t go down. He looked at Cortez (who had to have heard Stone’s directive from the corner), but the referee simply motioned for him to keep fighting.

But Ruiz had taken the fight out of Evander Holyfield, at least on this night. The next round he crushed him with a right hand that left him teetering in place for a moment before he crashed to the floor, and once he got up, Holyfield spent the rest of the night in such desperate retreat that he may not have thrown another punch.

Inevitably, the WBA ordered a rubber match. The only people happier than Holyfield himself were Chinese promoters who had been waiting in the wings after the second fight. They seemed to be only vaguely aware, if they were at all, that Holyfield was no longer the champion, but when King announced the August fight in Beijing, they seemed to have gotten their wish after all.

This particular Ruiz highlight doesn’t include Stoney, nor, for that matter, does it include the Quiet Man himself.

Despite sluggish ticket sales, the boxers were both already in China, as was King, that July. I had already secured a visa from the Chinese embassy in Dublin a few weeks earlier, and then after July’s British Open at Royal Lytham driven up to Scotland for a few days of golf.

St. Andrews caddies can often astonish you with the depth of their knowledge, but I guess if a man spends a lifetime toting clubs for the movers and shakers of the world he’s going to pick up a lot through sheer osmosis. And on this occasion I’d come across one who was a boxing buff as well. We’d repaired to the Dunvegan Pub for a post-round pint to continue our chat, and when the subject of Ruiz-Holyfield III came up, I told him I’d be on my way to China myself in a few days.

“Oh, I wouldn’t count on that,” he said ominously. I asked him why.

“Ticket sales are crap,” he said. “Ruiz is going to hurt his hand tomorrow. The fight’s not going to happen.”

The next day I got an emergency e-mail from Don King’s office announcing that John Ruiz had incurred a debilitating back injury and would be sidelined for several weeks. The Beijing fight was indefinitely “postponed.”

At least the paper didn’t make me fly home via Beijing.

* * *

The third bout between Ruiz and Holyfield took place at Foxwoods that December. When the judges split three ways, Ruiz kept the championship on a draw. He then beat Kirk Johnson, who got himself DQd in a fight he was well on the way to losing anyway, and then decided to cash in, agreeing to defend his title against Roy Jones for a lot more money than he could have made fighting any heavyweight on earth.

It was as clear beforehand as it is now that if Jones just kept his wits about him and fought a disciplined fight, there was no way in the world John Ruiz could have outpointed him. The only chance Ruiz had at all was a pretty slim one – that of doing something that would so enrage Jones that he took complete leave of his senses and succumbed to a war, where Ruiz would at least have a puncher’s chance.

The trouble was, Ruiz’ basic decency would never have allowed him to stoop to something like that. But Stone gave it his best shot.

The Jones-Ruiz fight took on such a monotony that it’s difficult to even remember one round from the next, but Stone’s weigh-in battle with Alton Merkerson was pretty unforgettable. Merkerson is big enough, and agile enough, to crush almost any trainer you can think of, and even in his old age I’d pick him over some heavyweights I could name. He’s quiet and reflective and so imperturbable that I’ve never, before or since, seen him lose his temper, and it’s fair to say that’s not what happened that day, either. When he saw Stoney flying at him, he thought he was being attacked (albeit by a madman), and reacted in self-defense.

Stone was in fact so overmatched that even he must have expected this one to be broken up quickly. Instead, boxers, seconds, undercard fighters, and Nevada officials fled in terror for the twenty seconds or so it took for Merkerson to hit Stone at least that many times. It was a scene so ugly that even Ruiz seemed disgusted. It wasn’t the end of their relationship, but it was surely the beginning of the end.

The public reaction to Jones’ win was an almost unanimous outpouring of gratitude. At least, they were saying, “we’ll never have to watch another John Ruiz fight.” But they were wrong.

He beat Hasim Rahman in an interim title fight that was promoted to the Full Monty when Jones affirmed that he had no intention of defending it. (Referee Randy Neumann, exasperated after having had to pry Ruiz and Rahman apart all night, likened them to “two crabs in a pot.) He stopped Fres Oquendo at the Garden six years ago, and then in November of 2004 came back from two knockdowns to outpoint Andrew Golota.

The Golota fight produced yet another Ruiz moment when Neumann, wearied of the stream of abuse coming from the corner, halted the action late in the eighth round and ordered Stone ejected from the building.

Most everyone found the episode amusing, Ruiz and Cardinale did not. LaMarca had retired, and while Stone was now the chief second, he was also the only experienced cut man in the corner. Having forced the referee’s hand, Stone had placed Ruiz in an the extremely vulnerable position of fighting four rounds – against Andrew Golota – without a cut man. Strike two.

Ruiz was reprieved when his 2005 loss to James Toney was changed to No Contest after Toney’s positive steroid test, but he bid adieu to the title – and to Stoney, it turned out – for the last time that December, when he lost a majority decision to the 7-foot Russian Nikolai Valuev in Berlin.

Already on a short leash, Stone had openly bickered with Cardinale the week of the fight, but his performance in its immediate aftermath sealed his fate. When Valuev was presented with the championship belt after the controversial decision, he draped it over his shoulder in triumph. Stone tore out of the corner and snatched it away, initiating a fight with an enemy cornermen. With Russians and Germans pouring into the ring bent on mayhem, Stone had to be rescued by Jameel McCline, who may have saved his life, but couldn’t save his job.

Four days later it was announced that Stone was retiring. Ruiz seemed bittersweet about the decision, but the two have not spoken since.

All of Ruiz’ significant fights over the past four and a half years took place overseas, and while he was well compensated for all of them, they might as well have taken place in a vacuum. Few American newspapers covered them.

I didn’t cover them either, but Ruiz and I did get together for a few days last fall out in Kansas, where we appeared with Victor Ortiz and Robert Rodriguez at a University boxing symposium. He’d brought along his new wife Maribel and his young son Joaquin, and the morning we were to part company we got together again for coffee and reminisced a bit more.

Neither one of us had seen Stoney, though I would hear from him, indirectly, soon enough. Newspapermen don’t write their own headlines, and a few months ago the lead item in my Sunday notebook for the Herald reflected on Ruiz’ upcoming title fight against David Haye in England representing this country’s last best chance at regaining the championship for what could be years to come.

When somebody at the desk put a headline on it that described Ruiz as an “American Soldier, word came back that Stoney – who had, remember, been an American soldier – was ready to dig his M-16 out of mothballs to use on me, Ruiz, or both.

Few Americans watched the telecast of Ruiz’ fight against Haye earlier this month, which is a pity in a way, because his performance in his final losing cause was actually an admirable one. In his retirement announcement he thanked trainers Miguel Diaz and Richie Sandoval “for teaching an old dog new tricks, and while the strategic clinch hadn’t entirely disappeared from his repertoire, it was not the jab-and-grab approach that may be recalled as his legacy.

And while Haye was credited with four knockdowns in the fight, three of them came on punches to the back of the head that would have given Bernard Hopkins occasion to roll around on the floor for a while. If somebody had decked Ruiz with three rabbit punches back in the old days with Stoney in the corner, the city of Manchester might be a smoldering ruin today.

* * *

When Ruiz officially hung up his gloves on Monday he did so with a reflective grace rarely seen in a sport where almost nobody retires voluntarily.

“I’ve had a great career but it’s time for me to turn the page and start a new chapter of my life, he said. “It’s sad that my final fight didn’t work out the way I wanted, but, hey, that’s boxing. I’m proud of what I’ve accomplished with two world titles, 12 championship fights, and being the first Latino Heavyweight Champion of the World. I fought anybody who got in the ring with me and never ducked anyone. Now, I’m looking forward to spending more time with my family.

In his announcement he thanked his fans, Diaz and Sandoval, Cardinale, his brother Eddie Ruiz, and his conditioning coach. He thanked everybody, in other words, except you-know-who.

Oh, yeah, one more thing. Ruiz, who has lived in Las Vegas for the past decade, now plans to move back to Chelsea. He hopes to open a gym for inner-city kids. “With my experiences in boxing, I want to go home and open a gym where kids will have a place to go, keeping them off of the streets, so they can learn how to box and build character.

I guess the question is: is Metropolitan Boston big enough for Ruiz and Stoney?

EDITOR’S NOTE: George Kimball, who spent most of his work life with the Boston Herald, passed away on July 6, 2011 at age sixty-seven. In his later years he authored the widely acclaimed “Four Kings: Leonard, Hagler, Hearns, Duran, and the Last Great Era of Boxing” and co-edited two boxing anthologies with award-winning sports journalist turned screenwriter John Schulian. This story appeared on these pages on April 27, 2010.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in The Fight Forum CLICK HERE

Featured Articles

David Allen Bursts Johnny Fisher’s Bubble at the Copper Box

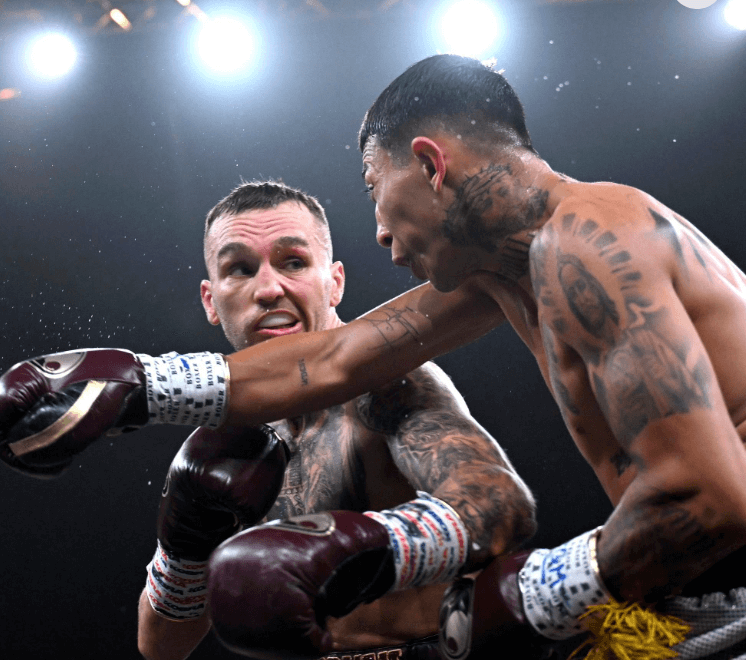

The first meeting between Johnny Fisher, the Romford Bull, and David Allen, the White Rhino, was an inelegant affair that produced an unpopular decision. Allen put Fisher on the canvas in the fifth frame and dominated the second half of the fight, but two of the judges thought that Fisher nicked it, allowing the “Bull” to keep his undefeated record. That match was staged last December in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, underneath Usyk-Fury II.

The 26-year-old Fisher, who has a fervent following, was chalked a 13/5 favorite for the sequel today at London’s Copper Box Arena. At the weigh-in, Allen, who carried 265 pounds, looked as if he had been training at the neighborhood pub.

Through the first four rounds, Fisher fought cautiously, holding tight to his game plan. He worked his jab effectively and it appeared as if the match would go the full “10” with the Romford man winning a comfortable decision. However, in the waning moments of round five, he was a goner, left splattered on the canvas.

This was Fisher’s second trip to the mat. With 30 seconds remaining in the fifth, Allen put him on the deck with a clubbing right hand. Fisher got up swaying on unsteady legs, but referee Marcus McDonnell let the match continue. The coup-de-gras was a crunching left hook.

Fisher, who was 13-0 with 11 KOs heading in, went down face first with his arms extended. The towel flew in from his corner, but that was superfluous. He was out before he hit the canvas.

A high-class journeyman, the 33-year-old David Allen improved to 24-7-2 with his 16th knockout. He promised fireworks – “going toe-to-toe, that’s just the way I’m wired” – and delivered the goods.

Other Bouts of Note

Northampton middleweight Kieron Conway added the BBBofC strap to his existing Commonwealth belt with a fourth-round stoppage of Welsh southpaw Gerome Warburton. It was the third win inside the distance in his last four outings for Conway who improved to 23-3-1 (7 KOs).

Conway trapped Warburton (15-2-2) in a corner, hurt him with a body punch, and followed up with a barrage that forced the referee to intervene as Warburton’s corner tossed in the white flag of surrender. The official time was 1:26 of round four. Warburton’s previous fight was a 6-rounder vs. an opponent who was 8-72-4.

In the penultimate fight on the card, George Liddard, the so-called “Billericay Bomber,” earned a date with Kieron Conway by dismantling Bristol’s Aaron Sutton who was on the canvas three times before his corner pulled him out in the final minute of the fifth frame.

The 22-year-old Liddard (12-0, 7 KOs) was a consensus 12/1 favorite over Sutton who brought a 19-1 record but against tepid opposition. His last three opponents were a combined 16-50-5 at the time that he fought them.

Also

In a bout that wasn’t part of the ESPN slate, Johnny Fisher stablemate John Hedges, a tall cruiserweight, won a comprehensive 10-round decision over Liverpool’s Nathan Quarless. The scores were 99-92, 98-92, and 97-93.

Purportedly 40-4 as an amateur, Hedges advanced his pro ledger to 11-0 (3). It was the second loss in 15 starts for the feather-fisted Quarless, a nephew of 1980s heavyweight gatekeeper Noel Quarless.

Photo credit: Mark Robinson / Matchroom

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

Featured Articles

Avila Perspective, Chap. 326: A Hectic Boxing Week in L.A.

The Los Angeles area is packed with boxing.

Japan’s Mizuki “Mimi” Hiruta, Ukraine’s Serhii Bohachuk, and the indefatigable Jake Paul are all in the Los Angeles area this week.

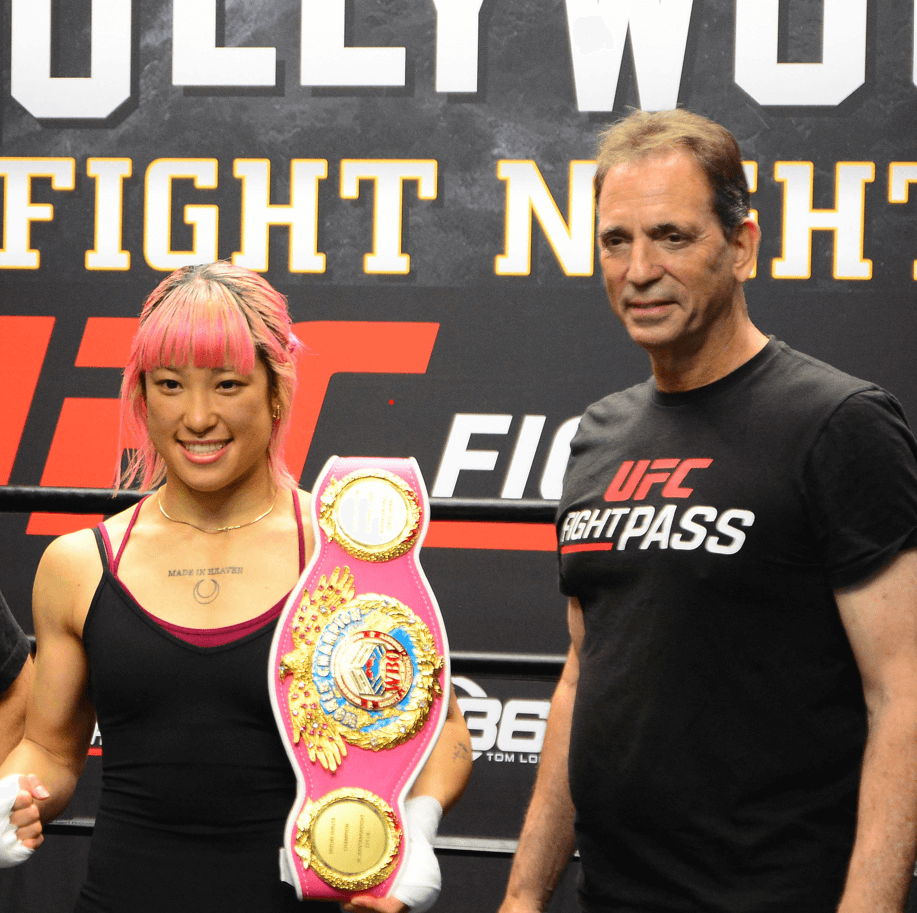

First, Hiruta (7-0, 2 KOs) defends the WBO super flyweight title against Argentina’s Carla Merino on Saturday May 17, at Commerce Casino. The 360 Boxing Promotions card will be streamed on UFC Fight Pass.

Voted Japan’s best female fighter, Hiruta faces a stiff challenge from Merino who traveled thousands of miles from Cordoba.

360 Promotions is one of the top promotions especially when it comes to presenting female prizefighting. Two of their other female fighters, Lupe Medina and Jocelyn Camarillo, will also be fighting on Saturday.

They are not only promoting female fighters. They have several top male champions including Bohachuk and Omar “Trinidad performing this Saturday.

Don’t miss this show at Commerce Casino.

“This card is one of the deepest cards we’ve promoted in Southern California which has been proven by the rush for tickets and the wealth of media interest. Serhii, Omar and Mizuki are three of the top fighters in their respective weight classes and it’s a great opportunity for fans to see a full night of action,” said Tom Loeffler of 360 Promotions.

Jake and Chavez Jr. in L.A.

Jake Paul took time off from training in Puerto Rico to visit Los Angeles to hype his upcoming fight against former world champion Julio Cesar Chavez Jr. next month.

“The fans have wanted to see this, and I want to continue to elevate and raise the level of my opponents,” said Paul, 28. “This is a former world champion, and he has an amazing resume following in his dad’s footsteps.”

Paul, who co-owns Most Valuable Promotions with Nakisa Bidarian, last staged a wildly successful boxing card that included Amanda Serrano versus Katie Taylor and of course his own fight with Mike Tyson.

It set records for viewing according to Netflix with an estimated 108 million views.

Paul (11-1, 7 KOs) is set to face Chavez (54-6-1, 34 KOs) in a cruiserweight battle at the Honda Center in Anaheim, Calif. on June 28. DAZN pay-per-view will stream the Golden Boy Promotions and MVP fight card that includes the return of Holly Holm to the boxing world after years in MMA.

No one should underestimate Paul who does have crackling power in his fists. He is for real and at 28, is in the prime of his boxing career.

Yes, he is a social influencer who got into boxing with no amateur background, but since he engaged fully into the sport, Paul has shown remarkable improvement in all areas.

Is he perfect? Of course not.

But power is the one attribute that can neutralize any faults and Paul does have real power. I witnessed it when I first saw him in the prize ring in Los Angeles many years ago.

Chavez, 39, the son of Mexico’s great Julio Cesar Chavez, is not as good as his father but was talented enough to win a world title and hold it until 2012 when he was edged by Sergio Martinez.

The son of Chavez last fought this past July when he defeated former UFC fighter Uriah Hall in a boxing match held in Florida. He has been seeking a match with Paul for years and finally he got it.

“I need to prepare 100%. This is an interesting fight. It might not be easy, but I’m going to do the best I can to be the best person I am, but I think I’m going to take him,” said Chavez.

Paul was not shy about Chavez’s talent.

“This is his toughest fight to date, and I’m going to embarrass him and make him quit like he always does,” said Paul about Chavez Jr. “I’m going to expose and embarrass him. He’s the embarrassment of Mexico. Mexico doesn’t even claim him, and he’s going to get exposed on June 28.”

Also on the same fight card is unified cruiserweight champion Gilberto “Zurdo” Ramirez (47-1, 30 KOs) who defends the WBA and WBO titles against Yuniel Dorticos (27-2, 25 KOs).

In a surprising addition, former boxing champion Holm returns to the boxing ring after 12 years away from the sport. Can she still fight?

Holm (33-2-3, 9 KOs) meets Mexico’s Yolanda Vega (10-0, 1 KO) in a lightweight fight scheduled for 10 rounds. Holm is 43 and Vega is 29. Many eyes will be looking to see the return of Holm who was recently voted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame.

Wild Card Honored by L.A. City

A formal presentation by the Los Angeles City Council to honor the 30th anniversary of the Wild Card Boxing Club takes place on Sunday May 18, at 1:30 p.m. The ceremony takes place in front of the Wild Card located at 1123 Vine Street, Hollywood 90038.

Along with city councilmembers will be a number of the top first responder officials.

Championing Mental Health

A star-studded broadcast team comprised of Al Bernstein, Corey Erdman and Lupe Contreras will announce the boxing event called “Championing Mental Health” card on Thursday May 22, at the Avalon Theater. DAZN will stream the Bash Boxing card live.

Among those fighting are Vic Pasillas, Jessie Mandapat and Ricardo Ruvalcaba.

For more information including tickets go to www.555media.com/tickets.

Fights to Watch

Sat. UFC Fight Pass 7 p.m. Mizuki Hiruta (7-0) vs Carla Merina (16-2).

Thurs. DAZN 7 p.m. Vic Pasillas (17-1) vs Carlos Jackson (20-2).

Mimi Hiruta / Tom Loeffler photo credit: Al Applerose

Featured Articles

Sam Goodman and Eccentric Harry Garside Score Wins on a Wednesday Card in Sydney

Australian junior featherweight Sam Goodman, ranked #1 by the IBF and #2 by the WBO, returned to the ring today in Sydney, NSW, and advanced his record to 20-0 (8) with a unanimous 10-round decision over Mexican import Cesar Vaca (19-2). This was Goodman’s first fight since July of last year. In the interim, he twice lost out on lucrative dates with Japanese superstar Naoya Inoue. Both fell out because of cuts that Goodman suffered in sparring.

Goodman was cut again today and in two places – below his left eye in the eighth and above his right eye in the ninth, the latter the result of an accidental head butt – but by then he had the bout firmly in control, albeit the match wasn’t quite as one-sided as the scores (100-90, 99-91, 99-92) suggested. Vaca, from Guadalajara, was making his first start outside his native country.

Goodman, whose signature win was a split decision over the previously undefeated American fighter Ra’eese Aleem, is handled by the Rose brothers — George, Trent, and Matt — who also handle the Tszyu brothers, Tim and Nikita, and two-time Olympian (and 2021 bronze medalist) Harry Garside who appeared in the semi-wind-up.

Harry Garside

Harry Garside

A junior welterweight from a suburb of Melbourne, Garside, 27, is an interesting character. A plumber by trade who has studied ballet, he occasionally shows up at formal gatherings wearing a dress.

Garside improved to 4-0 (3 KOs) as a pro when the referee stopped his contest with countryman Charlie Bell after five frames, deciding that Bell had taken enough punishment. It was a controversial call although Garside — who fought the last four rounds with a cut over his left eye from a clash of heads in the opening frame – was comfortably ahead on the cards.

Heavyweights

In a slobberknocker being hailed as a shoo-in for the Australian domestic Fight of the Year, 34-year-old bruisers Stevan Ivic and Toese Vousiutu took turns battering each other for 10 brutal rounds. It was a miracle that both were still standing at the final bell. A Brisbane firefighter recognized as the heavyweight champion of Australia, Ivic (7-0-1, 2 KOs) prevailed on scores of 96-94 and 96-93 twice. Melbourne’s Vousiuto falls to 8-2.

Tim Tsyzu.

The oddsmakers have installed Tim Tszyu a small favorite (minus-135ish) to avenge his loss to Sebastian Fundora when they tangle on Sunday, July 20, at the MGM Grand in Las Vegas.

Their first meeting took place in this same ring on March 30 of last year. Fundora, subbing for Keith Thurman, saddled Tszyu with his first defeat, taking away the Aussie’s WBO 154-pound world title while adding the vacant WBC belt to his dossier. The verdict was split but fair. Tszyu fought the last 11 rounds with a deep cut on his hairline that bled profusely, the result of an errant elbow.

Since that encounter, Tszyu was demolished in three rounds by Bakhram Murtazaliev in Orlando and rebounded with a fourth-round stoppage of Joey Spencer in Newcastle, NSW. Fundora has been to post one time, successfully defending his belts with a dominant fourth-round stoppage of Chordale Booker.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 322: Super Welterweight Week in SoCal

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks ago‘Krusher’ Kovalev Exits on a Winning Note: TKOs Artur Mann in his ‘Farewell Fight’

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoGabriela Fundora KOs Marilyn Badillo and Perez Upsets Conwell in Oceanside

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoFloyd Mayweather has Another Phenom and his name is Curmel Moton

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: The First Boxing Writers Assoc. of America Dinner Was Quite the Shindig

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 323: Benn vs Eubank Family Feud and More

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoChris Eubank Jr Outlasts Conor Benn at Tottenham Hotspur Stadium

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoJorge Garcia is the TSS Fighter of the Month for April