Featured Articles

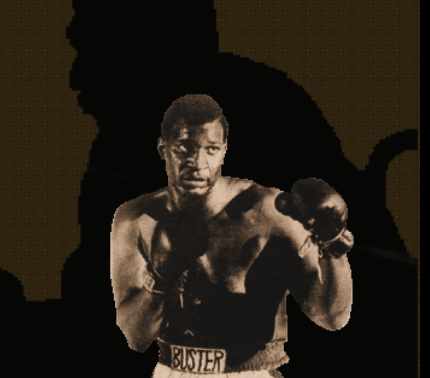

25 Years Ago Today, Buster Mathis, the Dancing Bear, Took His Earthly 10-Count

Sept. 6 marks the 25th anniversary of the death of former heavyweight contender Buster Mathis, who was 51 when he took his earthly 10-count in 1995. Although he never was a world champion, Buster, the dancing bear of a contender who came closer to making it all the way to the top than anyone of his overstuffed dimensions had any reasonable right to expect, may have already been dethroned in the court of public opinion in the one area where he once was thought to forever reign supreme.

By virtue of his shocking, seventh-round stoppage of IBF/WBA/WBO heavyweight titlist Anthony Joshua on June 1, 2019, in Madison Square Garden, Andy Ruiz Jr., another noticeably plump practitioner of the pugilistic arts, likely laid claim to the unofficial designation of “patron saint of fat heavyweights” that long before had been conferred upon Mathis, a legendary chow hound who once had dubbed himself a “world champion eater.”

It was an apt description, too, although the 6’3½” Mathis, whose one shot at a somewhat less legitimate world title (the vacant New York State Athletic Commission version, also recognized in Pennsylvania, Illinois, Maine and Massachusetts) had ended in an 11th-round knockout loss to his personal boogeyman, Joe Frazier, on March 24, 1968, weighed as much as 300 pounds only once as a pro, for his debut against Bob Maynard. But even when he tipped the scale in the high 220s and low 230s, Buster always appeared to be much heavier than he should have been. Try as he might to transform himself into a more presentable physical specimen, the Grand Rapids, Mich. product never could completely rid himself of the love handles that lapped over the waistband of his trunks like ocean waves breaking across a reef.

“I remember getting down as low as 229 pounds for one fight (in 1968, against Jim Beattie),” recalled Buster in May 1989, when I first interviewed him. “I looked pretty good, but I didn’t feel good. I felt really, really weak. I was so weak, I couldn’t break an egg.

“Man, did I have to work hard to get down to 230, 235 pounds. It wasn’t natural for me. I’d been over 300 pounds most of my life, so that’s the weight at which I felt most comfortable.”

The same might be said of Ruiz, who also apparently has given up on the notion that the aesthetics of appearance are as important to a fighter as genetics. If nature has decreed that an aspiring boxer is never going to snag a Calvin Klein underwear commercial, so be it. It is still possible to succeed, love handles or not, if one if fortunate enough to have been bestowed with surprisingly nimble footwork, quick hands, and a fundamental mastery of the nuances of a sport in which what you see isn’t always indicative of what you get.

In retrospect, it might be said that Buster Mathis – his son, Buster Mathis Jr., who prefers to be called “Bus,” also went on to become a heavyweight of some note – is at least a hard-luck figure, and possibly a tragic one given the myriad physical ailments his high-caloric lifestyle imposed upon him once he hung up his gloves and his weight continued to rise like a soufflé in the oven. Not that the elder Mathis’ 30-4 record, with 21 victories inside the distance, with more than a few of those bouts against elite-level opponents, is anything to casually dismiss, but had he emerged victorious in any of his three pivotal bouts – against Muhammad Ali (UD12) and Jerry Quarry (UD12), in addition to Frazier – it would have certified Buster as one of the best big men in an exceptionally deep era for heavyweights.

“I used to be really, really good. I think the record shows that,” Mathis told me for a story I did for the Philadelphia Daily News when he was training Buster Jr. for a run at the sort of ring glory that had always seemed to be just beyond the father’s grasp.

“Nobody my size ever moved like I did. In my neighborhood, if you wasn’t fast you’d be last. So I made myself fast. I might have been big, but I learned how to run on my toes. I even thought fast. When people called me names and told me I couldn’t do this or couldn’t do that, it only made me more determined to prove them wrong.”

But it is the loss to Frazier that rankled Mathis more than any other, in part because their clash was for a bejeweled belt but also because of the fact that it was Frazier, not Mathis, who was the United States’ heavyweight representative at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. Mathis actually had earned a spot on the USA team, but he broke a hand in training and was replaced by Frazier, the alternate, who went on to win the gold medal and enjoy the kind of Hall of Fame pro career that Buster, at best, only got to sniff.

Maybe it all had been preordained by fate, with the first tumbling domino of disappointment being Mathis’ unwise decision to part company with trainer Cus D’Amato, who had previously taken Floyd Patterson to the heavyweight championship and would later do so with Mike Tyson.

“I regret leaving Cus D’Amato,” Mathis said, whose son’s full name is Buster D’Amato Mathis. “There were people around me who kept saying that Cus would ruin my life, that I should be more independent. All Cus ever did was look out for me. He was one of the best things that ever happened to me in boxing.

“And the ’64 Olympics, that’s another big regret. I guess I’ve thought about that two million times. I had made the team, I was going to Tokyo. But then I broke my hand in training, and they replaced me with Joe Frazier. So what happens? Frazier wins the gold medal and goes on to become world champion. Would it have happened for me if I had gone instead? Man, I don’t know. But I can’t help but wonder.”

So, it was perhaps with a need to get some payback when Mathis, reasonably fit by his relaxed standards, came in at 243½ pounds for his matchup with Smokin’ Joe, four years after a still-raw Frazier had slid into the Olympic vacancy created by Buster’s busted hand. But Frazier, more polished than he’d been in 1964 and always a lights-out puncher, stopped his much larger opponent in 11 rounds.

“In the quiet hours, when I’m in my chair, lights out, everybody in bed, I think about Joe Frazier,” Mathis told me in a subsequent interview in 1994, the year before he died. “I bet I’ve fought Joe Frazier a million times in my mind. And you know what? I always beat him.

“But you can’t change the facts. You can cry over them when they don’t turn out your way, but you can’t change them. The fact is that when I did fight Joe Frazier, I lost. Got knocked out. I’m not complaining. I’ve had a pretty good life. I was never champion, but I guess everybody can’t get to be champion. I was fortunate enough to get close. That’s more than a lot of people in this business can say.”

Mathis was just 29 when he stepped away in 1972, after his final bout, a second-round knockout loss to Ron Lyle that may have convinced him that being nearly good enough was never really going to be good enough. Also, at 263 pounds for that fight, his ongoing war with weight appeared to be a battle he was destined from birth to lose, and, well, lose big. When he worked on the loading dock of the Interstate Trucking Company after his retirement from boxing, Mathis was known as the “Human Forklift” because of his size and strength. He reluctantly gave up that job when his doctors warned him of the dangers of overexertion.

In 1989, when he was 45, Mathis – who had ballooned to 500-plus pounds a few years earlier – had pared down to 330, primarily because of a diet free of saturated fats and the soft drinks he used to consume by the case. But he suffered from diabetes, hypertension and heart disease, and his already precarious health would continue to worsen; two strokes left him with limited motor control on his left side and forced him to use a walker. He suffered kidney failure in 1992 and had a pacemaker installed after a 1993 heart attack.

Although he continued to work with Buster Jr., who had taken up boxing as a means of avoiding the ongoing physical deterioration that seemed to be killing his father in stages, Buster Sr. no longer could demonstrate what he wanted his son to do in the ring. It was all he could do to sit in a chair at the Pride Boxing Club in Grand Rapids and tell Bus, by then the United States Boxing Association heavyweight champ, what to do, and even then on those increasingly rare occasions when he could summon enough energy to make it to the gym.

“I can’t show Bus what to do,” Mathis said. “My health isn’t good enough to allow me to do that.”

Medical bills, and maybe grocery bills, by then had so depleted the nest egg he had socked away from boxing that Mathis’ family, which included wife Joan and daughter Antonia, mostly subsisted on disability payments.

“I wasn’t dealt a good hand, but I’m doing OK,” he told me. “I’m not starving.” That last comment quickly elicited an ironic smile.

“I’m not starving, get it?” he said with a chuckle. “But then nobody ever could say that Buster Mathis was starving. Food is my weakness, my downfall. For some people it’s booze or drugs. For me, it’s always been food.”

It had been Buster Sr.’s dream to stick around long enough to help guide his son to a place higher on the heavyweight ladder than he’d been able to attain. It was not to be; Mathis was found unconscious by his wife at the family home in Wyoming, Mich., a Grand Rapids suburb. Family members and emergency workers tried to revive him, but he was pronounced dead upon arrival at Butterworth Hospital in Grand Rapids.

Brian Lee, Buster Jr.’s manager, said the father’s passing was not unexpected, but “it’s a blessing he went so peacefully after so many struggles, so many ailments. He was not afraid to die. He was comfortable with it.

“Not many people know this, but he was starting to lose his eyesight, too. He put on a brave front for the kids (in addition to Buster Jr., Mathis was working with 20 or so other young fighters). The gym kind of kept him going.”

Buster Jr., now 50, posted a 21-2 record with just seven wins inside the distance, an indication that, like his father, he was more a technician than a big blaster. Also like his father, he was acutely aware of his genetic predisposition to pack on pounds at an alarming rate. He was 325 pounds at 14, and his taking up of his dad’s profession was less a nod to his legacy than an acknowledgment that there really can be too much of a good thing.

“I just wanted to change my life,” Bus said in the lead-up to his Aug. 13, 1994, bout with Riddick Bowe in Atlantic City, which ended as a no-contest when Bowe, who was winning easily, made the mistake of hitting his opponent when he was down on one knee. “You know how it is in high school. The jocks wear the letter jackets and get all the girls. When you’re my size, though, you don’t have all that stuff. I didn’t have a girlfriend, and it was hard to shop for clothes. People don’t accept you when you are fat.

“But it’s not only that. I’ve seen what being too big for too long has done to my father. His health isn’t what it should be. For a long time I didn’t think about being big, because there are a lot of big people on my dad’s side of the family. I figured I was going to be big, too, because that’s just the way it is.

“Now I know it doesn’t necessarily have to be that way. Everybody has a choice.”

Check out more boxing news on video at the Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 330: Matchroom in New York plus the Latest on Canelo-Crawford

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoVito Mielnicki Jr Whitewashes Kamil Gardzielik Before the Home Folks in Newark

-

Featured Articles13 hours ago

Featured Articles13 hours agoResults and Recaps from New York Where Taylor Edged Serrano Once Again

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoCatching Up with Clay Moyle Who Talks About His Massive Collection of Boxing Books

-

Featured Articles5 days ago

Featured Articles5 days agoFrom a Sympathetic Figure to a Pariah: The Travails of Julio Cesar Chavez Jr

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoMore Medals for Hawaii’s Patricio Family at the USA Boxing Summer Festival

-

Featured Articles7 days ago

Featured Articles7 days agoCatterall vs Eubank Ends Prematurely; Catterall Wins a Technical Decision

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRichardson Hitchins Batters and Stops George Kambosos at Madison Square Garden