Featured Articles

How I Became a Boxing Writer

In 2010, I wanted to get back into boxing.

After enjoying the unforgettable 80’s and 90’s, my rooting interest in the cruelest sport waned in the wake of the 9/11 attack on America. When Lennox Lewis retired and the thrilling Gatti-Ward trilogy was history, I moved on. I didn’t watch much boxing in the first decade of the new millenium. I just wasn’t into the lumbering Klitschko brothers or the lighter-weight fighters.

That Christmas, my brother-in-law gifted me a subscription to The Ring Magazine, a print publication I had not enjoyed in many years. This awakened my interest in the Sweet Science. Soon I was commenting on boxing websites and dreaming of how to get more involved.

A childhood friend of mine from Brockton, Mass (the late Edwin Ayala) provided ultimate inspiration; getting hired a few years prior by Pedro Fernandez of “Ring Talk” to write up results from New England shows. Ayala, afflicted with a rare and incurable disease, inspired me. Soon, we were covering cards together and later, Ed left Pedro’s website to write and report for me.

Ayala, an Honorable Army Veteran, was 50 when he passed away on June 17, 2020. Ed suffered from a condition called Chorea-acanthocytosis. Despite this curse, my friend authored two short books, one a boxing fiction story entitled A Puncher’s Chance and the other an autobiography, Up Before The Count. He is survived by wife Loita and daughter Rosangela.

Rest in peace Ed.

HARD KNOCKS

I never went to journalism school.

My degree is in Criminal Justice from the University of Massachusetts. Later employed by Detective Joe Moura’s National Investigation Bureau (NIB) as a special investigator, I learned to gather hard to obtain facts and write detailed reports for clients. Some years after I left the field, Joe was hired by Arturo Gatti’s manager Pat Lynch to “prove” Gatti’s death was not a suicide.

In 2011, I was contacted by the administrator of a boxing website called Knockout Digest. A young Pinoy fellow named Bert Narvales asked me if I wanted to write articles and cover shows in New England. There was no pay but I jumped at the chance to live a dream, to find a way.

The first fight I was asked to cover was an HBO aired WBC welterweight title fight between Victor Ortiz and Andre Berto at Foxwoods Casino in Connecticut. This was my introduction to auxiliary media seating. Naive as I was, I expected to be sitting at ringside. Instead, Ed and I sat in the last row of the venue surrounded by loud and drunken fans. Ed was 5’7’’ while I’m 6’11’’.

My height helped me see the ring.

At an unforgettable post-fight presser, I questioned Ortiz about the close unanimous decision scores and whether he was certain of the victory. “In my mind and in my heart a fighter always knows if he won or if he lost or if it was close and I didn’t see it as close,” the beaming victor told me of beating Berto.

Theirs turned out to be the Fight of the Year.

DIGEST THIS

Bert’s boxing website wasn’t very well received. It was put together with press releases and other low-quality content. I wrote a few forgettable articles before figuring out I could do better myself. So, I left and created my own boxing blog. I used the experience and industry contacts I’d quickly picked up to join media conference calls, apply for press passes—and crash press row!

It was here (working at ringside) that I met Full Court Press publicist Bob Trieger. One of the few nice guys in boxing, Bob mentored me and shared his experiences with me. Though we don’t always see eye to eye, Bob remains a friend. I am grateful to him for showing me the ropes.

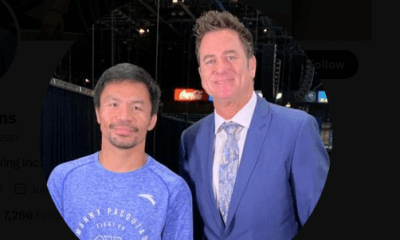

At an Edwin Rodriguez fight in 2012, Bob introduced me to Boston sports writer Ron Borges (pictured on my right) and later I got to work side-by-side with “KO JO” Jack Obermayer before Jack succumbed to liver cancer in 2016. Before he gave up the ghost, I carpooled with Obermayer (and fight writer Jeff Jowett) to cover the professional debut of Brandon “The Cannon” Berry in Skowhegan, Maine.

The media credentials piled up. My handheld tape recorder filled with boxing media content and fighter quotes. I wrote stories. I collaborated with two ringside photographers, Pattee Mak and Emily Harney. I became “an island of common sense in a sea of hysteria” or so said one reader.

I earned the respect of fans and fighters. Don Halpin, a Lowell journeyman who shared a ring with a young Mike Tyson in 1985, told me I did a great job of “keeping faithful readers up on what’s next, what’s gone down, and embracing the spirit of a sport that has given so many young men and women the means to reach for a dream.”

It was a special time in my life.

(Interesting thing about Halpin: Tyson hit him with an awfully late punch, a vicious uppercut, when Don was already down. Halpin endured arguably the worst of Tyson’s many fouls. It encapsulated the reality of Tyson early on in his career and the many blind-eyes turned to his flagrant acts of violence. Don told me he bears no ill-will towards Tyson despite acknowledging that Iron Mike was “trying to end a man’s life in the ring” at that point and that he’s glad Tyson was not successful with him—but not for lack of trying.)

THE SWEET SCIENTIST

Through the unfolding decade, I was fortunate enough to speak with and directly question many Hall of Fame fighters on media conference calls. I talked to Mike Tyson on one of these calls. George Foreman on another. Sometimes promoters would get testy with tough questions and rebuke a reporter. I’m pretty sure I got “yelled at” at least once by Bob Arum or Lou DiBella.

On my first such conference call, I somehow spoke with Lennox Lewis and Vitali Klitschko, asking both champions to recollect on their bloody 2003 heavyweight title fight in Los Angeles.

Lewis was humble but it was Klitschko who really gave me something, confessing: “I never met an opponent as strong as Lennox. I never took so many punches. I never looked so horrible.”

“Lennox Lewis was the hardest fight of my career.”

By 2013, I had put together a small team of contributors to meet the growing demand of my new readers. I used social media to promote our work—and it worked. I’m forever grateful to the eager writers who joined me and helped to make our website what it was—a success. They were David McLeod, Joel Sebastianelli, Derek Bonnett, Mark Jones, and Terence Strawson.

David still writes boxing (for photographer Ed Diller) in NYC, Joel is an Indy Car pit reporter who interviewed World Heavyweight Champion Wladimir Klitschko for KO Digest in 2014, Derek is a Dad, Mark is still expert in the world of women’s boxing, and Terry went on to promote shows.

Around this time, I was made an offer by experienced beat writer Lem Satterfield. Lem had heard me on conference calls and occasionally used quotes from my exchanges in his stories.

Lem wanted to know if I’d be interested in joining his “Ask The Experts” panel on RingTV. This was a group of reporters and insiders who penned predictions for upcoming big fights. Those predictions were then made into an article by Lem and published on the magazine’s website.

I built a reputation for prognostication.

That lasted nearly four years. British boxing writer Anson Wainwright later took over the popular column when Lem left and it was retitled as Fight Picks. I continued to contribute until 2017 when I was told the column would now only feature Ring magazine staff. Regardless, I’m truly grateful for the opportunity I was given by Lem to grow as a writer and expand my readership.

Though I was still writing for free, I was proving to anyone who might have been reading that I could actually do this boxing writing thing if given half a chance. I’d been published in boxing programs (Lowell’s Finest) and on the pages of Beyond The Badge, a law enforcement print periodical. KO was climbing the ranks in the small but competitive world of boxing media.

One of my earliest goals was to obtain a media credential for a big fight at Madison Square Garden in New York City. In 2013, I applied to cover Fury-Cunnigham and “KO Digest” was approved. Unfortunately, I didn’t make it to MSG to cover Tyson’s dramatic comeback when the Boston Marathon bombing caused all Amtrak trains out of Massachusetts to be suspended.

Incredibly, the bomber was a local amateur boxer. Because I closely covered the 2012 Lowell Golden Gloves and made basement contacts there, I was one of the first people in the boxing media to make the connection and report on it. How? Gloveboy Ryan Lones messaged me during the manhunt with a photo of an old boutsheet bearing the name Tammy Tamlor.

Such was the misspelling of Tamerlan Tsarnaev.

I continued to work hard. I improved as a writer. I grew as a journalist. Every day was something new to write and report about. Articles, ratings, interviews, predictions, live shows. KO Digest was running regularly scheduled features. Keeping up with all that was a full-time job for me.

One that still didn’t pay. (To Be Continued…)

Part 2: Pressrow at Madison Square Garden, Breaking Heavyweight News, Hired by The Sweet Science, Auxiliary Acceptance by the Boxing Writers Association of America, On The Beat in Boston, Winning My First Bernie, Boxing Writers Breakfast of Champions.

—

Boxing Writer Jeffrey Freeman grew up in the City of Champions, Brockton, Massachusetts from 1973 to 1987, during the Marvelous career of Marvin Hagler. JFree then lived in Lowell, Mass during the best years of Irish Micky Ward’s illustrious career. A new member of the Boxing Writers Association of America and a Bernie Award Winner in the Category of Feature Under 1500 Words, Freeman covers boxing for The Sweet Science in New England.

Check out more boxing news on video at the Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoVito Mielnicki Jr Whitewashes Kamil Gardzielik Before the Home Folks in Newark

-

Featured Articles7 days ago

Featured Articles7 days agoResults and Recaps from New York Where Taylor Edged Serrano Once Again

-

Featured Articles6 days ago

Featured Articles6 days agoResults and Recaps from NYC where Hamzah Sheeraz was Spectacular

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoFrom a Sympathetic Figure to a Pariah: The Travails of Julio Cesar Chavez Jr

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoCatterall vs Eubank Ends Prematurely; Catterall Wins a Technical Decision

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoPhiladelphia Welterweight Gil Turner, a Phenom, Now Rests in an Unmarked Grave

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoMore Medals for Hawaii’s Patricio Family at the USA Boxing Summer Festival

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoCallum Walsh, Umar Dzambekov and Cain Sandoval Remain Unbeaten at Santa Ynez