Featured Articles

Lloyd Price, Music, and Boxing (1933-2021)

Music was the lifeblood of the youth culture when I was young. I came of age during the “Golden Age of Rock and Roll” and expanded my appreciation to other eras. I’ve been fortunate in that the profession I’ve chosen has enabled me to spend time with some of the icons of my youth. Muhammad Ali heads the list. But there have been many others, including some from the world of music.

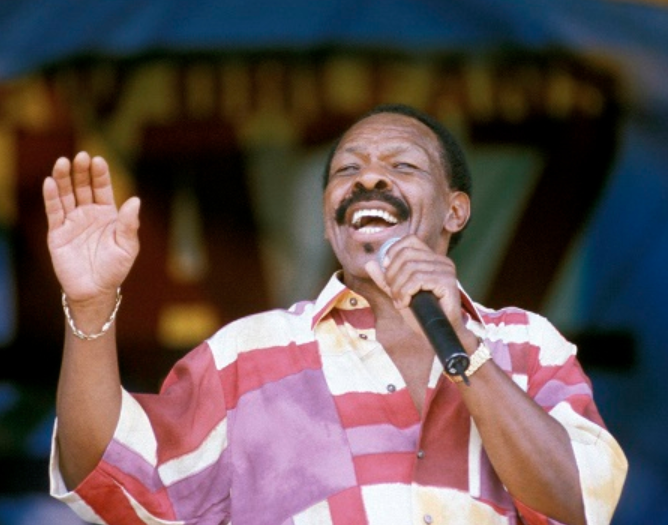

Over the years, I’ve been privileged to meet Ella Fitzgerald, Harry Belafonte, Little Richard, Chubby Checker, Glen Campbell, Mary Travers, Ramsey Lewis, and others. I also spent time with Lloyd Price. Lloyd died in a longterm care facility in suburban New York on May 3 at age 88. A word of remembrance is in order.

Price was born in Louisiana in 1933 and grew up in the segregated American south. He was one of the early pioneers of rock and roll at a time when major radio stations in the United States wouldn’t play rock and roll by Black recording artists. Nat King Cole and Johnny Mathis were given airtime. But “race music” was forbidden. That gave rise to a phenomenon known as the “white cover” version. A Black artist like Little Richard would write and record a song like Tutti Frutti that received limited exposure. Then Pat Boone or another white singer would release a “socially acceptable” version that might sell a million copies.

In the mid-1950s, a white disk jockey in New York named Alan Freed began playing “race music”. The time was right. The Civil Rights Movement was gathering steam. In February 1959, for the first time ever, a rock and roll song sung by a Black recording artist became the best-selling “pop 45” in the nation. The singer was Lloyd Price.

In 1952 at age 19, Price had written and recorded a song called “Lawdy Miss Clawdy.” In 1958, he updated and recorded a song called Stagger Lee that dated back to 1911. Stagger Lee rocketed to #1 on the Billboard charts in the United States. One year later, Price wrote and recorded Personality which became an international hit.

What does this have to do with boxing?

Price had appeared in small clubs after the release of Lawdy Miss Clawdy. As Stagger Lee rose to the top of the charts, he was booked into the Top Hat Lounge in Louisville, Kentucky. When he arrived at the club, a tall good-looking teenager was waiting outside for him.

“I was on tour,” Price told me years later. “Ali was sixteen years old, sitting outside because he was underage and they wouldn’t let him in. When I got to the lounge, this crazy kid rushed over, saying, ‘Mr. Price, I’m Cassius Marcellus Clay; I’m the Golden Gloves Champion of Louisville, Kentucky; someday I’m gonna be heavyweight champion of the world; I love your music; and I’m gonna be famous like you.’ I just looked at him, and said, ‘Kid, you’re dreaming.’ But we got along. You couldn’t help but like him. The Top Hat Lounge was a popular place, and each time I played there, I saw him. After a while, I started looking for him and bringing him in with me. He had all sorts of questions – about music and traveling, but mostly he wanted to know about girls. There were a lot of things he didn’t know, and he asked me how to make out with girls. He was very sincere about it. I told him, ‘Just be yourself, and the girls will like you.’ Although as part of the lesson, I gave him a couple of dollars and said, ‘Always have some money. That’s the beginning of hanging out with the foxes.’”

Thus began a lifelong friendship.

“You have to remember what America was like at that time,” Price explained later. “In parts of the country, I’m being booked into white clubs. I’m being booked to do white dances. But I can’t stay at the white hotel and I have to go around to the back door if I want a sandwich. I went to some [Nation of Islam] meetings with Ali. For the first time in my life – as a grown man who was a star who had sold millions of records – I heard somebody saying, ‘You are somebody.’ The language gave you such a lift. You left feeling good about yourself. In the end, it wasn’t my thing. But I can understand how Ali got hooked.

“That’s how our friendship started,” Lloyd continued. “Then, after he turned pro, he came to New York and stayed with me at my apartment several times. Right before he fought Doug Jones, I drove him around town to publicize the fight. That was my red Cadillac he was in.”

Price was a savvy businessman. He kept the copyright to most of the songs he wrote and founded several record labels. He’s also the man who introduced Ali to Don King.

“I used to go to Cleveland because my song-writing partner, Harold Logan, lived there,” Lloyd reminisced. “I knew all the people Harold knew and, through him, I got friendly with Don. One day, I was over at Don’s place in the kitchen talking about Muhammad. Don’s daughter Debbie said, ‘I want to meet him.’ It was her birthday. She was about five. So I telephoned Muhammad and he sang Happy Birthday to her over the phone. Then Don got on and started talking. He was strictly a Cleveland man at the time. He didn’t know anything about New York or Chicago or Los Angeles. And he was into numbers, not boxing. But that was the introduction. He and Ali got together – once I think it was – and then Don went to prison. But when he got out, you could see the wheels turning in his mind.”

After King was released from prison, he prevailed upon Price to call Ali and ask if Muhammad would box in a charity exhibition to benefit the Forest City Hospital in Cleveland. Ali did it for free. History suggests that the primary financial beneficiary of the event was King, not the hospital. Later, Price was a key figure in orchestrating the Zaire 74 music festival in Kinshasa held in conjunction with the historic “Rumble in the Jungle” between Ali and George Foreman. And in 1980, he tried his best to talk Ali out of coming out of retirement to fight Larry Holmes.

“I kept thinking about a day I’d spent in New York with Ali and Joe Louis maybe ten years earlier,” Price told me. “Joe had been with me because there was a little bird singing in my band who he liked a lot, and Ali and I had been friends for years. Somehow or other, we got together and they were talking, mostly about boxing. I was listening. They got along well that day, no tension of any kind between them. Ali asked, ‘Joe, tell me something. What happens in the ring when you get old?’ He was asking about Joe’s fight against Rocky Marciano, when Joe was 37 years old with that bald spot in the middle of his head, when he got knocked through the ropes and was counted out. Joe said, ‘Ali, let me tell you something. When I was young and wanted to throw a punch, I could throw it as fast as I wanted. But when I got old, my brain would tell me to do something and my arms just wouldn’t do it.'”

“Don’t fight Holmes,” Price told Ali. “It’s over. Father Time is calling. You’ve got to hear the bell.”

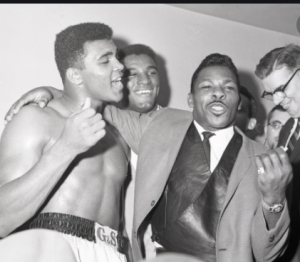

Price with Ali and Ali’s brother Rahman Ali

“You don’t know nothing about boxing and getting old,” Ali retorted. “You’re a singer, not a fighter.”

Then Price told Ali a story about going out on a national tour in 1963. As a favor to a friend who was trying to break into the music business, he agreed to let one of the friend’s groups open for him. The arrangement lasted until Price realized that the warm-up act was getting more applause than he was. So being a showman, he sent them packing with the request that his friend send him a different opening group.

“Who did you get rid of?” Ali asked.

“Some guys I’d never heard of before,” Price told him. “Smokey Robinson and the Miracles. And the next opening act made me look even worse. The first night they were on, when they finished their set, there was such pandemonium that I told the band to take a ten-minute break before I went out so the audience could calm down and I wouldn’t look bad by comparison.”

“Who were they?”

“Three Black chicks called the Supremes.”

Price then called his friend (who, of course, was Berry Gordy in the process of launching Motown records) and told him to stuff his groups where the sun didn’t shine. “Just send me one guy to open,” he instructed.

Whereupon Berry Gordy sent Marvin Gaye.

“And that was it,” Price told Ali. “I said to myself, ‘I don’t know what these folks have. But whatever it is, I don’t have it.’ So I took myself off the road, bought a club in New York [that he called Turntable], and signed a fifteen-year contract to promote concerts for Motown in Manhattan. I heard the bell.”

Over the years, I saw Lloyd maybe a dozen times. The most memorable of these occasions was a night when he and Ali were guests for dinner at my apartment. After dinner, I put an old LP of Lloyd Price’s Greatest Hits on the turntable and we sang along. There were seven of us. Ali was beginning to have trouble speaking at that time in his life. But that night he sang louder than the rest of us.

The last time I saw Lloyd, he was well into his eighties, thinner than before and walking with a cane. But his voice was clear. There was a gleam in his eye. And his contagious laugh still filled the room. I’m grateful that I had the opportunity to know him.

Thomas Hauser’s email address is thomashauserwriter@gmail.com. His most recent book – Staredown: Another Year Inside Boxing – was published by the University of Arkansas Press. In 2004, the Boxing Writers Association of America honored Hauser with the Nat Fleischer Award for career excellence in boxing journalism. In 2019, Hauser was selected for boxing’s highest honor – induction into the International Boxing Hall of Fame.

Check out more boxing news on video at the Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 330: Matchroom in New York plus the Latest on Canelo-Crawford

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoVito Mielnicki Jr Whitewashes Kamil Gardzielik Before the Home Folks in Newark

-

Featured Articles17 hours ago

Featured Articles17 hours agoResults and Recaps from New York Where Taylor Edged Serrano Once Again

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoCatching Up with Clay Moyle Who Talks About His Massive Collection of Boxing Books

-

Featured Articles5 days ago

Featured Articles5 days agoFrom a Sympathetic Figure to a Pariah: The Travails of Julio Cesar Chavez Jr

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoMore Medals for Hawaii’s Patricio Family at the USA Boxing Summer Festival

-

Featured Articles7 days ago

Featured Articles7 days agoCatterall vs Eubank Ends Prematurely; Catterall Wins a Technical Decision

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRichardson Hitchins Batters and Stops George Kambosos at Madison Square Garden