Featured Articles

Every Joe Gans Lightweight Title Fight – Part 3: George “Elbows” McFadden

This was the seventh meeting of the rival lightweights. In all previous ones McFadden held his own, making a brave stand against the colored wonder. Since then, Joe Gans has been on the upgrade. – San Francisco Call, June 28, 1902.

Joe Gans celebrated winning the lightweight championship of the world by fighting. It was how he made money. As a rule, the bigger the fighter got and the whiter the fighter got, the more he might find himself making easy money in theatre and foregoing the ring. The likes of John Sullivan spent literally years milking the title in theatre productions that caused for little more in physical exertions than a pulled punch thrown at an over-awed actor. For an African-American champion in a lighter weight class, such opportunities were less common.

To see Joe Gans in the ring, though, the public would always pay.

Gans took four fights in two days back in Baltimore, all slated for four rounds, all victories inside the distance. One might sneer at the soft opposition but in fairness, they all managed to do more minutes than Frank Erne.

Real work was to begin though, and it came in a familiar form.

George “Elbows” McFadden, “a champion in any other era” according to Nat Fleischer, was a white lightweight who charged himself with a near impossible task in 1899: he set out to outfight not just Joe Gans, but Frank Erne and Kid Lavigne, too. He went 9-2-2 that year, and 2-2-1 against the trinity of Erne, Lavigne and Gans. He met Gans three times.

No lightweight has ever engaged a higher level of competition in a single year and although the likes of Harry Greb and Henry Armstrong probably had harder years overall, even in that company, McFadden’s 1899 is welcome.

Most extraordinary was his relative inexperience, remarked upon in the days before his first match with Gans. Boxrec sees him at 20-3-12; by contrast Gans had already amassed a record of at least 68-4-8. Most of all, McFadden was stepping up not by a single class, but by three, by five, out of the pack and into a ring that would birth a legitimate title contender.

“McFadden gave the most remarkable display of blocking ever seen in a local ring,” reported the Saint Paul Globe the morning following the fight. “Gans tried in every way to get in on the New-Yorker but was invariably stopped. If McFadden blocked with his left he sent his right to the body and sent the left to the face.”

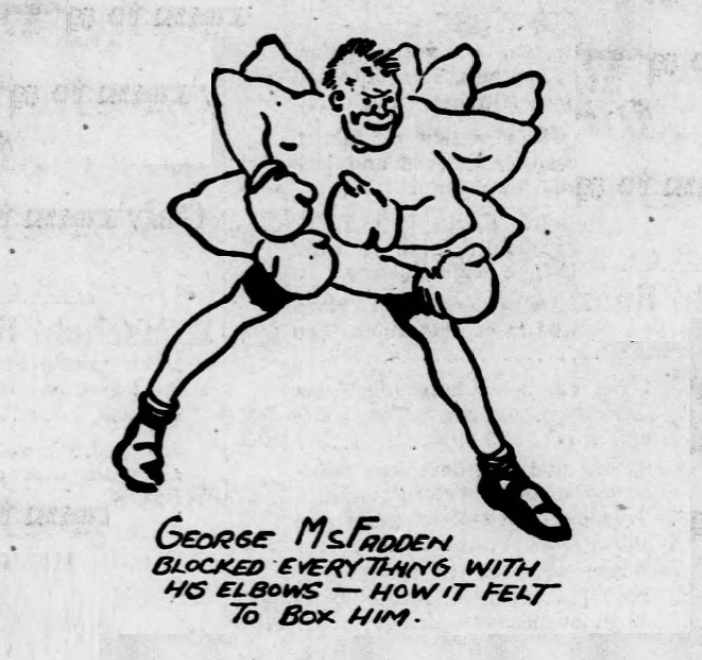

McFadden, a defensive specialist, earned his nickname not for throwing his elbows, as might be expected, but rather as one who used them to pick off punches, a mobile guard that he used to protect his body, like a pioneering Winky Wright, but also his head, perhaps in an early incarnation of the cross-arm guard. “My elbows ensured their fists stayed away from my chin” was how McFadden himself put it. As an in-fighter and a counterpuncher, a fluid cross-arm guard deployed out of a crouch at close quarters makes sense, as ably demonstrated by Archie Moore some decades later. Whatever the specifics, McFadden relied heavily upon his defence in beating Joe Gans in their first meeting, on April 4th 1899.

McFadden was a slow starter. He never troubled Gans, really, in their six-round contests. Every time they contended over a longer distance though, McFadden made Gans miserable and never more so than in the first of their three New York contests. Once he achieved for himself a lead in the contest, he rarely let it slip. McFadden’s strategy was essentially to keep Gans physically close to him, buying his way in with his elite blocking and parrying, then being economical with his leads, minimising opportunities for Gans to punish him. It is an intimidating strategy and it worked for McFadden, forcing Gans to move continually. By the close of the 18th round of their first fight, Gans appeared tired to ringsiders. In the twenty-third, McFadden opened with two rights to the body and a left to face which visibly distressed Gans; McFadden then leapt upon him and delivered a right to the jaw followed by a hooked left to the chin and Gans was out.

McFadden, in his first fight at boxing’s highest level, had done what no man had done before and arguably what no man would ever legitimately do again until the very twilight of Joe’s career: he had knocked Joe Gans out.

Retrospectively, the enormity of this achievement cannot be overstated. Arguably, this is the best result under Marquis of Queensberry rules from the nineteenth century.

McFadden dropped a razor-thin decision to Frank Erne a month later and then met Gans in a rematch; this fight was close and not decisive. Gans worked left-handed, jabbing and hooking, McFadden pressured him and threw bodypunches. As the rounds progressed, Gans began the painful process of uncovering McFadden’s great weakness – an excessive reliance upon specific punches on offence. When he jabbed, it tended to be to the body; left-handed headshots seemed his shot of choice in clinches. Right-handed bodyshots, too, were expressly favoured, at least against Gans. The list of punches that required neutralisation was short. Having perhaps been unlucky not to be awarded a draw against Erne, in his second fight with Gans McFadden seems lucky to have received one, although he did pull out all the stops in an astonishing last round, fighting a stunned Gans “to a standstill” after being dropped himself in the twenty-fourth.

Gans finished the job he started in that second fight almost exactly three months later in the pair’s third meeting of the year, finally out-pointing McFadden over the twenty-five-round distance, but only after a difficult, bruising tussle. McFadden fought one of his most aggressive fights but despite great success to the body he was firmly outboxed by Gans who repeatedly tagged McFadden flush. “Elbows” confirmed his defensive prowess and punch resistance in seeing out the distance, but Gans had finally solved the McFadden problem. McFadden would manage another draw with Gans, over ten rounds in 1900, but he would never again defeat him.

McFadden’s 1899 performance, though, was astonishing. As well as defeating Gans and dropping the narrowest of decisions to Erne, he beat former champion Kid Lavigne, by knockout. Since, he had lost two six-round fights to Gans and one to Gus Gardner. He almost immediately rematched Gardner over a longer distance and won by disqualification. That his 1902 title shot against Gans was to be his only fight for a title is a testimony to the strength of the era. His continued absence from the Hall of Fame is an absurdity.

Although it would seem to make sense that the contender who most troubled Gans pre-title should be his first defence, the fight came about almost accidentally.

McFadden had a fight scheduled for San Francisco, but prospective opponent Jimmy Britt injured his hand; McFadden’s manager, Billy Roche, received a telegram inviting his charge instead to fight the newly crowned Joe Gans.

Although there are some stories that he was unhappy with the notion of yet another fight with Gans, McFadden accepted. He would fight anyone, and in the days of the colour-line appeared never once to have thought about it. Whatever the race or size of the prospective opponent, McFadden’s reply only ever concerned remuneration, although it should be admitted that McFadden may have preferred Britt. For his own part, Gans had “established a precedent for American pugilists to ponder” in meeting McFadden, according to the San Francisco Chronicle, “one of the hardest propositions of his weight now in the game. Gans is not an actor, nor does not care to shine in any place but the ring.”

Both men were primarily motivated by money, but their willingness should not be overlooked. Gans-McGovern VII was on.

McFadden arrived in San Francisco on the 9th of June 1902; Gans was just a few days behind him. Gans was remarkably confident for a man who had previously been knocked out by his opponent, although as was almost always the case pre-fight, much of his talking was done by manager Al Herford.

If talk was cheap then the public were buying; Gans was made a significant favourite in the betting, which would nevertheless remain light. Herford was disgusted at the odds. “I think Gans will win sure,” he told pressmen, “but I have been at the ringside every one of the six times they have come together before and I know it is not a 2 to 1 bet that my man will win.”

As far as I can tell, the two-thousand dollars he wished to wager remained in his pocket.

“The fight will take place at Woodward’s Pavilion,” reported the San Francisco Examiner. “Both men are reported to be in splendid shape and should the contest be honestly fought those who attend will doubtless be treated to a boxing exhibition of the highest order.”

As we saw in Part Two, however, Chicago cast a long shadow.

“Unfortunately,” continued the Examiner, “…the remembrance of shady transactions in the career of Joe Gans have incurred a feeling of doubt in the minds of ring patrons that is difficult to remove. Of his several notorious fakes, the one with Terry McGovern in Chicago, on December 13, 1900, stands out from all the rest, and is still fresh in the memory of those familiar with his record.”

McFadden declared himself in the finest of condition; the Examiner agreed “his general appearance denotes the truth of his words.”

His general appearance, perhaps, was deceptive; then again, perhaps Gans really had improved beyond measure between 1899, when these two were marked as equals, and 1902 when Gans made himself forever McFadden’s superior. The fight was neither close nor difficult, but it nevertheless divided onlookers: was it real, or had Gans once again been involved in a fixed fight?

The wire report was both succinct and in essence tells the reader all they needed to know about the action as it occurred:

“The fight was an unsatisfactory one. In the first two rounds McFadden was slow and did nothing but block. In the third, Gans landed a stiff left on the jaw, following it with a right in the same place, putting McFadden out.”

The devil though, as always, is in the detail. First and foremost, it must be noted that McFadden often started slowly and with an emphasis on defence and this was not uncommon when he met Gans. McFadden appeared to feel his way into fights in order to achieve his best results, which is why he had given Gans such terrible trouble over the longer distance. McFadden waiting and blocking was not unusual but drew ire in the light of the early stoppage.

The Chronicle saw a legitimate fight, but a deeply unsatisfying one.

“Gans was declared the winner of the whatever the bout may be called,” ran the story on page four the day after the match, “certainly not a fight, for it takes two men to fight; perhaps assault would fit the case better.”

The Call, too, called it above board but below par:

“There is not the slightest possibility of the fight being a “fake” in the sense of being prearranged. It was simply an unfortunate match, which looked well on paper, only to prove a fizzle when the men faced one another in the ring.”

But the Examiner saw a different fight.

Under the headline “Sporting Public Swindled by Another Fake Fight” it printed that “The farce was kept up for three rounds…[t]here was not at any stage of the game enough pretence of fighting to delude the spectators. Before the first round was half over they began crying, “Fake! Fake!” These cries increased as the exhibition progressed, McFadden never letting go a blow that was intended to hurt and Gans declining to punch his opponent’s waiting jaw when it was held up to him.”

In the following days, the Examiner worked hard to source proof of a fake but to no end. They pushed referee Phil Wand right to the edge of agreement; he claimed calling the fight a farce would be “charitable” but saw no evidence of collusion. The Examiner is a minority report and although it cannot be dismissed, it should be noted that Gans had his enemies in San Francisco, not necessarily without reason but perhaps neither without bias.

Herford, concerned with the accusations against his charge, astonished the Examiner into begrudging retreat when he appeared at the newspaper’s offices with a thousand dollars in cash, the equivalent of thirty thousand today, offering it as a forfeit should anyone produce evidence of a fake. “It is not likely that anyone will accept Herford’s offer” concluded the Examiner.

Nevertheless, the stink was such that Hayes Valley Athletic Club announced that it would be withholding the fighter’s purses “until it was clearly shown that the fight was not a fake.”

Little more than a week later, George Siler, writing in the Chicago Sunday Tribune, reported an end to the matter:

“After a thorough investigation, in which every known angle was gone over carefully, the managers of the Hayes Valley athletic club, under whose auspices Joe Gans and George McFadden recently battled, concluded the above-named fight was strictly on the level. The cry of “fake” which went floating over the country immediately after the fight was caused by two reasons: One because McFadden was supposed to give Gans a terrific battle, and the other because the colored champion had been engaged in shady ring transactions.”

This, it seems to me, is exactly what happened. McFadden always gave Gans a fight and his shocking capitulation in combination with the controversy connected to the McGovern fight led to a response in fight fans that will not be unfamiliar to modern followers of the game. The simple truth was that the champion had improved since 1899, had gone from a fighter losing in a disorganised headclash in twelve to Frank Erne, to one who had destroyed the reigning champion in just seconds. McFadden was being crushed as a part of the same ghost-wave that had drowned Erne.

“Gans,” stated the Call, “with his marvellous ability as a boxer, was all over McFadden from the first moment.”

“It seemed the fight would not last one round when Gans sent a right and left to the head, followed by another right that seemed capable of felling an ox,” the report continued. “He kept this rapid fire up for nearly a minute and it was a miracle McFadden did not succumb to it. At times it seemed Gans did not take advantage of all his chances.”

The Call was on hand, and we, unfortunately, were not, to see what reads like a seminal performance from one of the ten greatest fighters ever to draw breath. Therefore, we must take seriously the diagnosis of a failure in Gans to take advantage of all his opportunities. Nevertheless, it must be remembered what McFadden was, however one-sided the fight: a defensive specialist with years of experience, including nearly one-hundred rounds against Gans himself.

The Chronicle was near despairing in describing round two:

“Gans hit his man at will and without return. Twice the white man hit the floor. Neither time did he take the count. In fact, he seemed as though in a trance, and, when he arose, made no effort to protect himself.”

To a modern eye it wills seem clear that McFadden had been concussed by the vicious attack in the first. Even after the fight, McFadden remained alarmingly non-responsive.

“McFadden could hardly speak,” ran one report of his condition in his dressing room. “He had to be shaken roughly to get a word out of him.”

It may not be an exaggeration to say that his life was in danger as prime Joe Gans, as terrifying a pound-for-pound incarnation as had been seen in the ring, stalked him throughout the third, showing little in the way of mercy.

“Gans punished McFadden terribly,” wrote the Call of the third and final round. “He knocked him clean off his feet with a right to the jaw. McFadden was no sooner up than he was knocked down again. He was up again and staggered to the center of the ring. He tried to hang on, but the elusive Gans seemed never where he expected to find him. McFadden was knocked down twice before the end of the round.”

As the final seconds of the third round approached, McFadden second George Tuthill perched himself ringside and prepared to throw the sponge. As McFadden was battered around the ring. he tossed it, signalling the end of the massacre and of McFadden’s time as a contender to the title. In his future, still, there were impressive performances against the likes of Mike Sullivan and Patsy Sweeney, but never again would he reach the heights he displayed in achieving the result of KO23 Joe Gans.

Some years later, after his forty-two-round battle with Battling Nelson in Goldfield, someone asked Joe Gans if this had been his toughest fight. “No sir,” he replied. “Bat is tough, but I met a tougher fellow than him. That fellow was George McFadden.”

As an epitaph, it is far from displeasing.

The noise surrounding the purported fix was such that what Gans had achieved was obscured. Six weeks apart, he had smashed Frank Erne, champion, out of title honours in a round and then destroyed a chief contender and his chief rival from his pre-title days in three. Neither man had lain a meaningful glove upon him. My position is that Joe Gans boxed the greatest championship reign in all of boxing built primarily of dominance and over exceptional opposition, opposition better than that of other, numerically comparable reigns.

I will prove that to you over the coming weeks.

This series was written with the support of boxing historian Sergei Yurchenko. His work can be found here.

Check out more boxing news on video at the Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Book Review2 weeks ago

Book Review2 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles7 days ago

Featured Articles7 days agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRahaman Ali (1943-2025)

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoTop Rank Boxing is in Limbo, but that Hasn’t Benched Robert Garcia’s Up-and-Comers