Featured Articles

Every Joe Gans Lightweight Title Fight – Part 2: Frank Erne II

The lightninglike character of the defeat struck consternation into the hearts of the thousand Erne men at the ringside. They were dumfounded. Their champion had met defeat before he had fairly begun to fight. – The Brooklyn Eagle, May 13, 1902.

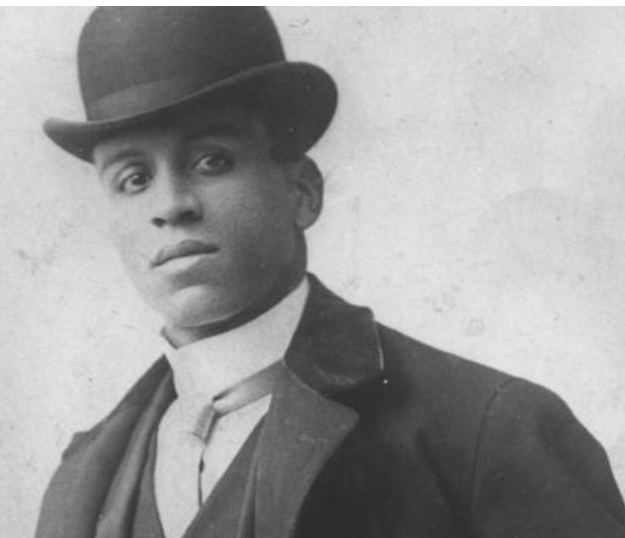

At the end of Part 1, we left Joe Gans with a career it tatters. By quitting to Frank Erne in a world title fight and then colluding in an apparent fix against Terry McGovern, Gans had committed the two mortal sins of the ring. Months after the McGovern debacle The Waterbury Democrat ran a speculative piece under the headline “Is Gans Chicken Hearted?” More than a year after the first Gans-Erne fight, the St.Paul Globe reported on Joe’s attempts to break into the San Francisco fight scene: “Fortunately Gans’ evil reputation has preceded him and the ‘Frisco sports are consequently forewarned and forearmed against the threatened coming of that most undesirable negro pugilist.”

His name was mud.

Erne, for his part, was clear: he would take “no notice of challenges directed” by, or on behalf of, Joe Gans. Ahead at the time of the stoppage, Gans was twice disgraced, and a fighter Erne needed no part of. Gans, though, had been a professional for eight years before he tempted Erne into the ring and knew the two-part equation for forcing a champion’s hand: kick ass and take names.

This work started in earnest in the May of 1901, some months having elapsed since his miserable hippodrome against McGovern. His opponent that day was the wonderful Bobby Dobbs, the old-time “colored” lightweight champion, too vulnerable, perhaps, to be compared directly to Gans but a boxer of some brilliance. His career spanned five decades and during it he took to the ring more than two-hundred times. Suffice to say, he was no pushover, a veteran of the ring who had a decade and more of fighting before him. Gans “made a chopping block” of the wily Dobbs who did not land a meaningful blow according to the wire report. Gans was back in earnest.

That said, nothing more underlined his being drawn back into the chasing pack of lightweights than the fact that he was now once more battling for the “colored” lightweight championship. This title is viewed in modern times, rightly, as something of an ignominy but in fact various “colored” titles were fought for as late as the 1940s and often by men as good as or better than the reigning “world” (and by implication, white) champion. This title worked as a chokepoint for black contenders, a way of thinning out the ranks of African-American fighters who sought championship fights. Black fighters first had to prove themselves the best black fighter, and then they might be allowed to fight for the real title. Gans then, sought to prove himself once more.

He hit a bump in the road against the excellent Steve Crosby in August, boxing a twenty-round draw in a fight he dominated, his soon-to-be-legendary blocking bedrocking an inspired generalship that kept Gans in control throughout. But Crosby, too, was a fighter of no small talent and in the nineteenth, he rushed Gans and was not turned away. The pattern of the fight had seen Gans pin Crosby to the ropes at the end of exchanges, here, instead, Crobsy held his ground and a tired Gans was outhustled in both the nineteenth and twentieth rounds.

Joe clinching his way through the late stages looked bad; the referee, according to the wire report, “could only call the match a draw.”

Gans was no longer a young man and I think this was the last major lesson he learned in the ring. As Jack Blackburn would tell Joe Louis three decades later, “let your fist be your judges, Chappie.” Gans was the best technician of his generation, more, the best technician in history up until that point. Like every technician he hIn January of 1901 he stopped Bobby Dobbs for a second time and what had been clear once before was clear again: Joe Gans was far and away the best of the African-American lightweights and deserved another chance at the champion.ad a question to answer, and that question was more urgent in the early 1900s, with fights often scored on the general impressions of the referee: when to cut loose. Gans wasn’t quite given the chance to answer in the immediate rematch, which was stopped by police interference while Gans battered Crosby about the ring, but it is no coincidence that Gans scored four quick knockouts in his next four fights. These included a one round stoppage of Joe Handler, a man who had never been stopped and was himself coming off a win over the excellent Spike Sullivan. Gans, perhaps, had a redeveloped a mindset, one fixated on stoppage victories even over class opponents he had tended to seek to outgeneral.

Erne, for his own part, was not without problems. Not least among them was the same Terry McGovern with whom Gans had performed his disastrous charade; McGovern had put a much more legitimate hurting upon Erne at a catchweight. A sojourn to 147lbs in search of a second championship had also seen him hurt. There were those that saw the champion slipping just as they saw Gans beginning to surge.

Surge, and surge irresistibly, for around January a rematch was planned for February. A six-round no -decision whereby Gans would have to win by stoppage to take the title, it seemed little more than an exhibition and very much in keeping with the Philadelphia law of the time. It was also the first step on the road to a legitimate second fight for the world’s lightweight title.

The Buffalo Courier, which watched Buffalo resident Frank Erne’s every move, speculated as to the significant financial rewards which must have been on offer to induce Frank to face a man he had sworn off fighting before noting that Erne’s title was for the most part protected by the ruleset. Gans’ compliance in boxing six was all but implied and there seemed little chance, anyway, of Erne succumbing in six to a technician like Gans. Nevertheless, the paper reported on January 19th that the contest “will be worth going a distance to see. While they fought at long distance [in their first fight], Gans damaged the Buffalo boy considerably.”

Both things were true, and people did indeed go a distance to see the Philadelphia fight that February – only for Erne to no-show.

This was not a carefully considered withdrawal, either, but a panicked last-minute dereliction of duty leaving an angry crowd disappointed at the gate – not quite the equal to the sins perpetrated by Joe Gans, but only a single magnitude lower.

Erne spoke freely of a plan to “do him”, that Gans, clearly in superb condition, plotted to attempt to knock Erne out, an accusation denied vociferously by Gans. This sounds strange to modern ears – why would Erne be upset at the notion that Gans would try to knock him out? And why would Gans deny it? They were fighting, weren’t they? They were, but laws differed by state in America at the time and there were perceived differences in different types of fighting. Erne’s expectations of an exhibition rather than a prizefight were not unusual; there were even stories that Gans had posted a thousand-dollar bond against his winning by stoppage.

That this would not be considered a fix where the Gans-McGovern fight was very much in the shades of grey associated with the era. In fact, Erne only disgraced himself by the lateness of his withdrawal – the accusation of a double-cross was otherwise taken seriously.

Still, having won all but one of his previous eight contests by stoppage – including a Philadelphian six-rounder with Joe Youngs, who he beat into retirement in just four – Gans cast a shadow so menacing as to intimidate even Erne. Erne wanted time, time to improve his shape and perhaps to reclaim his confidence. Softer fights were made for the champion at lightweight while negotiations began in earnest to make the championship match Erne had probably now doomed himself to fight. If Erne had given the impression of handling Gans over six, he could perhaps postpone meeting him in a title fight indefinitely; now it seemed only a question of where and when.

By late March, all was known. The fight had found its way north of the border and into Canada. It made no difference to Erne, nor Gans, natural-born road-warriors both, where the fight might be fought; the Athletic Club at Fort Erie on May 12th was as good a spot as any, three thousand dollars guaranteed ending the argument. Gans celebrated by dusting Jack Bennett in three; Erne, who had stopped Curley Supples (better known for wrestling) and then exercised himself over the six-round distance against Gus Gardner earlier in the month, eschewed further combat and settled into training.

Some of that training took place at his father’s Lewiston farm where his mother once more took control of training camp logistics. His final training base was planned for Niagara, but the improvised camp did not agree with Erne; he returned to Buffalo and the Rose Street gym he called home. He trained before pressmen who were suitably impressed.

“I feel a hundred percent, better than I ever did before,” Erne replied in questions to his condition.

Erne sparred three rounds with chief second Frank Zimpfer, then shadowboxed. “To say that Erne is faster on his feet than ever before,” reported The Courier, “is only giving him partial credit. Erne’s puzzling and wonderful footwork, if nothing else, is bound to give Gans trouble.”

“They tell me Joe is working like a Trojan,” offered Erne. “Well he can’t be in better shape than he was the night we clashed in New York…I think Gans will play a rushing game. I rather expect him to fight fast from the gong.”

Gans was indeed “working like a Trojan” down in Leiperville, Pennsylvania; Terry McGovern, clearly bearing no grudges over the considerable fallout from their contest, had done some sparring with Gans and then loudly picked him to defeat Erne. Gans always sought out serious sparring partners and much of his work had been done with the wonderful Young Peter Jackson and Herman Miller, who had himself boxed a pair of draws with Dobbs. Al Herford, Joe’s manager, expressed his satisfaction at the condition of his charge and that all their claims upon Erne and the title would evaporate with a loss. For Gans, it was to be now or not at all.

He arrived in Fort Erie forty-eight hours before bell, around the same time as professional gamblers began pouring into town. Odds were in his favour, barely, though they had been fluctuating since the fight was made and would continue to do so until first bell: Gans, evens, Erne, and back, though never was the difference vast.

“A bet on me will get the money,” Gans told The Courier. “I will lick Erne sure. He beat me once, but it was an unfortunate accident. He couldn’t do it again in twenty years.”

Erne disagreed. “I’ll still be lightweight champion of the world Tuesday morning,” he said. “I will knock out Gans in ten rounds or win the decision at the end of twenty.”

There was some concern in print over the moral certitude of the combatants. Between them they had a quit job, a fake and a no-show in just two short years; overwhelmingly though there was excitement, the type that only a true superfight can engender. The Courier was enthusiastic concerning their hometown fighter’s condition to the point of sycophancy:

“That Erne is in the best of physical condition is a foregone conclusion. He is in better shape at present than he ever was before. Erne of tomorrow night will not be the same Erne of two months ago. He is down to weight, fast as a colt, his skin is rugged, his eyes are bright, and flash like a panther’s. His wind is perfect, his hands are sounder than ever before, and, in general, he is the same Erne who won the championship from “Kid” Lavigne some three years ago. Erne is hitting harder and faster now than he ever did in his life.”

And even where past transgressions were to the fore, as they were in The Chicago Inter Ocean, Gans may have remained a “despicable human being” but was nevertheless an “ugly and dangerous ring partner…it behooves you to watch him closely.”

Gans was first to the ring, “as lean as a wolf hound” according to The Buffalo Review; Erne did not make him wait, arriving only minutes later appearing “trained to the hour.” The crowd stood in preference of Erne but Gans not without his backers. One by one, Kid Parker, Kid McPartland, Art Sims and George McFadden presented themselves and their challenges – more fighters issued challenges to one another. The weights of the two principals were announced, Gans just under 134lbs, Erne just under 133lbs. At 9:49pm the two shook hands. At 9:41pm Frank Erne writhed on the canvas in a futile attempt to beat the count.

“After knocking at the door for ten years,” wrote The Brooklyn Eagle, “Joe Gans, the Baltimore lightweight colored pugilist, at last is the lightweight champion of the world.”

“The knockout punch was so clever,” continued The Washington Post, “so sudden, so unexpected and so quick that even Gans and referee Charley White stood motionless for an instant, staring at the form of Erne as he lay on his stomach, apparently unconscious.”

The two had emerged cautiously, sparring, each man trying to induce the lead, as they had in the first fight, a competition Gans had won. Here Erne seemed more determined, shifting, while Gans danced at the very edge of reach. Erne finally reached Gans with a right-hand punch, but it was at the very end of his reach and did no harm. If there was a warning shot for Erne this was it, a punch not thrown by Gans but by himself: at the full extent of his reach, he was both powerless and vulnerable. He needed to either commit to attack or commit to remaining at safe distance, he could not do both.

The first seriously landed punch was a Gans left, but a jab, as if in portent though it drew blood from Erne’s nose. Both men were trying to feint each other out of position but Gans, just as he had been in the first fight, was the man controlling the distance. It was Erne that had to take action to close that distance, to change the pattern of the fight, and here he did so, stepping in with a punch.

“Erne feinted with his right,” saw The New York Evening World, “and as he did so Gans also feinted with the same hand. Erne, evidently thinking that Gans was going to swing for his jaw, ducked, and as he did so Gans sent in a short but terrific right jolt under Erne’s left guard. The blow landed with terrible force on Erne’s nose, mouth and chin.”

The punch was an uppercut, whipped straight through the Erne guard. He collapsed face-first to the canvas, some descriptions having him tangle with Gans as he fell.

The Washington Times takes up the story:

“The six thousand or more men in the arena were simply petrified with amazement. For the first three seconds not a single person moved or spoke. Then of a sudden a mighty cheer burst forth. Men jumped to their feet and surged towards the ring.”

The Inter Ocean provided the tragic details of Erne’s desperate struggle:

“One, two, three, and Erne’s quivering body stretched out. Four, five, and he partly raised himself on one arm, only to roll over on his face at the count of six. Seven, and Erne, with a game effort, worked his hands under him. Eight, nine and out.”

Gans had won in a hundred seconds.

“Did he knock me out?” demanded Erne as he was carried to his corner by his seconds and then began to weep. Gans was hoisted into the air and carried from the ring.

There was some bad feeling associated with the result. Some talk of a “lucky punch” reached the ears of Al Herford who marched his charge out of town early the following day, resulting in Frank Erne, this time, being stood up, as he arrived in town for a meeting with Herford the following morning to discuss a potential rematch. Herford claimed Gans was keen to be reunited with his wife, “his fourth” sniffed a clearly pained writer for The Buffalo Evening News.

Those seeing a lucky punch included Terry McGovern who was ringside but a lightweight named Joe Leonard, the instructor at the Buffalo boxing gym, was also ringside, and gave a more thoughtful perspective:

“I was close to the ring,” said Leonard, “and I had a good view of the doings. I also noticed that Gans, in stepping in with his final punch, pivoted partly around on his knee – just as I have seen Kid McCoy do. That put additional force in the blow. I have seen a good many fights, but never before did I see anyone show such fine generalship as did Gans in feinting Frank into that angle where he had him dead to rights. Erne fell into the trap easily and Gans was there with one of the cleverest punches I ever saw delivered.”

Whether a lucky punch or a masterful trap, there was no doubting the result, nor the winner. Erne would never fight for the world title again – though he did fight for something called the “white” world title. Gans, the first man of colour to lift the lightweight championship was about to become the fightingist champion of any weight in the short history of boxing.

His first defence would see the end of a war fought in numerous chapters, stretching back to the summer of 1899.

This series was written with the support of boxing historian Sergei Yurchenko. His work can be found here.

Check out more boxing news on video at the Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoResults and Recaps from New York Where Taylor Edged Serrano Once Again

-

Featured Articles7 days ago

Featured Articles7 days agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoResults and Recaps from NYC where Hamzah Sheeraz was Spectacular

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoFrom a Sympathetic Figure to a Pariah: The Travails of Julio Cesar Chavez Jr

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoPhiladelphia Welterweight Gil Turner, a Phenom, Now Rests in an Unmarked Grave

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoCatterall vs Eubank Ends Prematurely; Catterall Wins a Technical Decision