Featured Articles

Forged by Longtime Coach Al Mitchell, Mikaela Mayer Seems Destined for Stardom

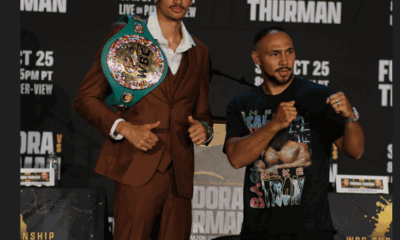

Mikaela Mayer makes the first defense of her WBO 130-pound world title on Saturday at the Virgin Hotels in Las Vegas against her toughest opponent yet in Argentine veteran Erica Anabella Farias. A win by Mayer would be another feather in the cap of her 77-year-old trainer Al Mitchell who is one of boxing’s most interesting personalities.

One of the bedrocks of amateur boxing in America, Al Mitchell grew up in Philadelphia in one of the city’s toughest neighborhoods. “Most of the kids on my block would eventually go to prison,” says Mitchell.

Some of them spent time in prison with Mitchell who got caught up in the street life as a teenager and was remanded to the city’s Holmesburg Prison whose alumni would come to include Bernard Hopkins. When he got out, he went back to the recreation center where he had learned to box but rather than resuming his amateur career, he found coaching more to his liking.

In 1988, Mitchell took a team of boxers to a Junior Olympics tournament at the Olympic Education Center in Marquette, Michigan. Founded in 1985, the center was designed for the purpose of allowing elite athletes to continue their education while providing them with the resources to maximize their athletic potential. Athletes of college age attend classes tuition-free at Northern Michigan University and reside with their younger cohorts in the school’s dorms. For many years, NMU was home to the National Junior Olympics Tournament.

In an oft-told story, when Mitchell was returning with his team to Philadelphia, he came across a 15-year-old boxer from Georgia who was stranded at the airport. Mitchell called the kid’s mother and promised her that he would see that her son got home safely and let his Philadelphia team go on ahead without him.

The 15-year-old boxer was Vernon Forrest who would turn pro under Mitchell’s tutelage and go on to win world titles in two weight classes.

The honchos at the training center were impressed with Mitchell’s compassion and with the tools displayed by the young boxers he brought there. The coaching position was vacant and they induced Mitchell to take the job. He arrived in Marquette in the summer of 1989. He reckoned that he would only be there for a few months.

From a ‘hood in Philadelphia to a sleepy college town in Michigan’s Northern Peninsula is quite a transition. Marquette is white; not predominantly white, just white. And then there’s the weather. Arriving in the summer, Mitchell didn’t appreciate how cold it would get when winter set in. In December, January, and February, the average daily HIGH temperature in Marquette is below freezing.

Mitchell acknowledges that he almost left several times. His boxers, notably Vernon Forrest and Ricky Ray Taylor, a Golden Gloves champion from the Mississippi Gulf Coast who never turned pro and currently trains boxers in New York, talked him out of it. In time, however, Mitchell settled in. When the weather is nice, he says, Marquette is the most beautiful town in the world. And the locals were more than welcoming.

After three years in the NIU dorm where he lived on the same floor as his boxers, Mitchell, who is divorced, purchased a home. It’s four blocks from the shoreline of Lake Superior and one-and-a-half blocks from the college. When he is gone for any length of time, he can count on his neighbors to mow his lawn.

“My neighbors all have the keys to my house,” he says. “In Philadelphia that would never happen. Around here, if I hear bang, bang, bang, I know that it’s just a car backfiring.”

Mitchell was never shot, but he was brutally attacked by robbers during the time that he owned a North Philadelphia bodega, a place where most walk-ins came to turn in their numbers, i.e., their selections in the daily lottery-type game that was once a staple of community life in America’s ghettos.

The assailants got him when he was closing up for the day and left him in such bad shape that he spent five days in a coma during a lengthy hospital stay. He bears a souvenir of the incident, a plate in his head.

Mitchell was named the head coach of the 1996 U.S. Olympic team that included Floyd Mayweather, David Reid, Fernando Vargas, and Antonio Tarver, and was a consultant to the 2004 and 2012 squads, the latter of which was the first to include women.

The greatest U.S. Olympic team was the 1976 edition that won seven medals (five gold) in Montreal. They set the benchmark against which future squads would be unfairly compared.

There were 11 weight divisions in 1976, a number that would grow to 12 and currently sits at eight for boxers with male chromosomes. A boxer faces more hurdles today as there are more boxing federations which has given rise to more international qualification tournaments. Back in the days of Sugar Ray Leonard and the Spinks brothers, notes Mitchell, a U.S. Olympic boxer who made it all the way to the finals wouldn’t have faced more than one Russian. “Today he may face three.”

By that he means that in the old days, fighters from such countries as Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan would have been classified as Russians. Following the break-up of the Soviet Union, those countries became separate entities. And they have mirrored the Russians and Cubans by investing heavily in their amateur athletes with stipends and other perks that encourage their boxers to delay or forego their entrance into the professional ranks.

Mitchell has proposed moving the Olympic boxing competition from the summer to the winter. With a less cluttered cast of athletes, dispersed over fewer sports, there would theoretically be room for the International Olympic Committee to reinstate the discarded weight divisions. In the United States, this would inevitably translate into more ink for the boxing team, raising the profile of a sport that many no longer consider mainstream.

Mitchell’s proposal fell on deaf ears.

As for the U.S. delegation in Tokyo — five male and four female – Mitchell says it’s a solid team with the women likely to out-perform the men because they have stayed in the program longer. Two of the four women – Ginny Fuchs and Naomi Graham – are in their thirties. On the men’s side, Duke Ragan is the granddaddy at age 24.

The last American to win a gold medal was Andre Ward who accomplished the feat at the 2004 Games in Athens. Ward has morphed into a color commentator for ESPN Boxing where he has impressed knowledgeable fans with his insightfulness.

Al Mitchell, who worked extensively with Ward before he turned pro, isn’t surprised. “Ward and Floyd Mayweather, who was on my 1976 team, had the highest ring IQs of all the boxers that I have coached. When I first worked with Andre, I thought this kid doesn’t punch hard enough to go very far. But he had great anticipation and no one was better at processing what his opponent had and making the right adjustments. I had no doubt that he would perform better against Kovalev in their second meeting than he did in their first.”

Mitchell notes that Andre Ward’s sidekick Tim Bradley is also one of his former students. “He also does a great job and I couldn’t be happier for him.”

Mitchell’s style of coaching has been likened to that of a drill sergeant. He would roust his boxers out of bed at 5 am to go running and it made no difference what the weather was like outside. His gruff demeanor when putting his boxers through their paces may have been inherited from his father, a staff sergeant during the Korean War who returned home with PTSD symptoms and died when Al was 16.

Needless to say, many of the boxers who come to Marquette don’t have the fortitude to stay there very long and who can blame them? It’s no picnic, to put it mildly. When Mikaela Mayer first turned up, Mitchell assumed that she would hang around for a few weeks, at most. She fooled him. Asked to identify her chief asset, Mitchell cited her work ethic. The two have been together now for 11 years.

Mitchell had no interest in teaching women how to be better boxers – “My father would turn over in his grave,” he told ESPN’s Mark Kriegel – but with women now eligible to fight in the Olympics, he felt he had little choice. And Mayer owes her success to more than just a good work ethic. Mitchell and his top assistant Kay Koroma have crafted her into a very formidable fighter who, at age 30, perhaps has yet to reach her peak. (And by the way, she’s a lot more attractive than the photo of her that appears in boxrec, whoever that may be; it certainly doesn’t look like her.)

Back in Philadelphia before boxing became all-consuming, Mitchell concedes that he was a hustler. In addition to having his fingers in the illegal numbers game, he ran a speakeasy. He must have been a hard-boiled guy in those days but one wouldn’t know it if meeting him for the first time today. He comes across as a gentle soul although one suspects it wouldn’t be a smart idea to give him any lip.

For her fight with Erica Farias, Mikaela Mayer spent four weeks at Mitchell’s gym in Marquette (which is no longer formally attached to the university which currently supports athletes in only two Olympic summer sports; Greco-Roman wrestling and weightlifting), then three weeks at the Olympic and Paralympic Training Center in Colorado Springs, finishing up with a week at the Top Rank Gym in Las Vegas.

Her bout with Farias will be the co-feature of a show headlined by the WBA/IBF bantamweight title fight between Japan’s baby-faced assassin Naoya Inoue and Filipino challenger Michael Dasmarinas. The bouts, and a third fight between Adam Lopez and Isaac Dogboe, air free on ESPN with a start time of 7 pm ET. Undercard action commences at 5 pm ET on ESPN+.

Check out more boxing news on video at the Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Book Review4 weeks ago

Book Review4 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Debunking Two Myths and Other Notes

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoNikita Tszyu and Australia’s Short-Lived Boxing Renaissance

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoKotari and Urakawa – Two Fatalities on the Same Card in Japan: Boxing’s Darkest Day

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoIs Moses Itauma the Next Mike Tyson?

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRamirez and Cuello Score KOs in Libya; Fonseca Upsets Oumiha

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoBoxing Odds and Ends: Paul vs ‘Tank,’ Big Trouble for Marselles Brown and More