Featured Articles

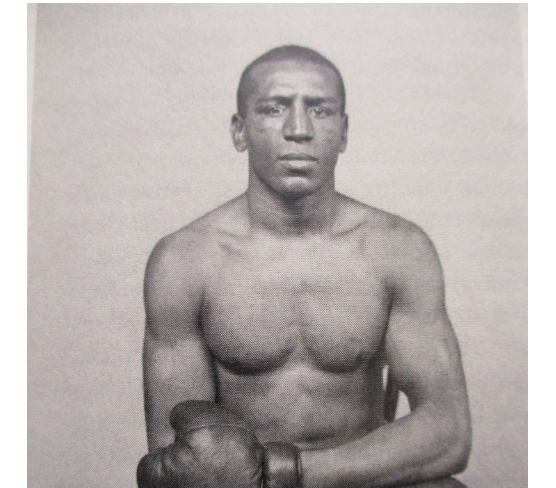

Every Joe Gans Lightweight Title Fight – Part 6: Charley Sieger and Gus Gardner

Where did you get this fellow? – Joe Gans, November 14 1902.

I have embarked upon some difficult projects over the past thirteen years writing about boxing but nothing as challenging as this. Joe Gans was popular in his own time but sourcing information about him is difficult. He was, after all, a sportsman and not a president and he stopped boxing well over a hundred years ago.

Fortunately, Sergei Yurchenko has done a great deal of good work in the area of making understanding Joe Gans less difficult. Sergei isn’t my writing partner in any traditional sense and English is not even his first language, but I am very happy to say that there is no Russian anywhere who knows more about Joe Gans than he. It might be that there is nobody of any nationality than knows more about Joe Gans than he.

If I have questions, he has been able to answer them, and then I have done my best to bring those answers to you. Any failure to do so is mine and not his. So, give his website a click here; this is a site aimed directly at boxing obsessives with an interest in the history, and if you are reading part six of this series, you are that.

So let me take you back once more, this time to Autumn of 1902. Theodore Roosevelt had just become the first American President to ride in a car; Mount Pelée again erupts in Martinique, killing a thousand people; the first ever science-fiction film was released to stunned audiences in Paris, France; and Joe Gans took a month off.

When he returned to the ring it was to defend his title against contender Charley “The Iron Man” Sieger. Prior to October of 1902, Sieger would have been a fighter with no right to occupy a ring holding Joe Gans for any reason other than to provide sparring, but on the third of that month, Sieger beat out a fading George McFadden over twenty rounds and in Baltimore no less, where Gans still made his base. McFadden, perhaps still reeling from the three-round pasting he received at the hands of Gans, started so slowly as to cede the first five rounds and clawing the deficit back was clearly beyond him. Repeatedly slashes to the neck and upper torso left McFadden’s skin red-raw and although Sieger lacked power, he appeared quick-handed and accurate.

More than this he was at that time known for durability and although McFadden made the occasional impression upon him with uppercuts and right hands, he was never turned away.

Sieger stated his intention at the outset to make a match with Joe Gans should he beat McFadden and although Buddy King, a lightweight who was making waves out in Denver seemed to be in the frame, it was soon clear that it would be Sieger. McFadden tried to insert himself into the conversation with talk of a bad training camp and the poor climate disagreeing with him, but his time as a contender was over.

Gans began his training in Baltimore with Herman Miller and Raymond Coates, arriving at the gym in fair shape, impressing when he performed before an audience in the Eureka Athletic Club and finished his training in Leiperville, Pennsylvania where no less a figure than Young Peter Jackson arrived to provide serious opposition in sparring. No detailed account of their spars seems to have survived, such occurrences commonplace to those who witnessed them, such nonchalance almost beyond belief to those with an interest in such things now – suffice to say there was as much skill and guile on display in those spars as would be present in most fight-rings for the first half of the twentieth century. Jackson would meet the immortal Joe Walcott twice after these spars and lost neither contest.

Gans believed he would win, according to The Baltimore Sun, “but as usual, he did not boast.” Sieger, meanwhile, was training in Baltimore’s Maryland Gym aided by several fighters including featherweight Tommy Daly. “[He] is working hard,” reported The Baltimore American, “as he realizes that this is the chance of his life.”

Sieger has the appearance, now, of an unsatisfactory defence, but this was not so in the moment. New Yorkers began hunting tickets, some of them through the Broadway Athletic Club, which took notice. A short piece in The Baltimore Morning Herald described Sieger’s status in New York that of a valid contender. He was regarded in New York as “the coming lightweight champion”. New York letters began to arrive in Baltimore seeking odds. Sieger was himself was reportedly confident, although early in fight week he spoke only of “lasting the distance” a target that he perhaps felt might afford him opportunities to score the knockout blow as the fight came down the straight.

This was arguably valid strategy and a notion explored by too few Gans opponents at this time. A strange tussle at the halfway point of his first fight with Frank Erne had seen Gans quit; he had been stopped very late in a twenty-five-round contest with McFadden; Gans certainly had his successes over the longer distance, but he had two longform draws, too. Extending him may have seemed a reasonable strategic choice in late 1902.

Gans appeared ready when he arrived in Baltimore from his camp in Leiperville on the very day of the contest. Sieger met him at three that afternoon for the weigh-in where they both hit the 133lb mark whereupon Sieger decamped for the Germania Maennerchor Hall where he set out to survive for the distance of twenty rounds with the new championship edition of Joe Gans.

It was a fool’s errand; but such was the bravery and determination with which he set himself forth to achieve the unachievable that he emerged with his reputation enhanced. “In Sieger’s dictionary,” reported The Baltimore American, “there is not written the word quit.” The same paper noted that for Gans, Sieger represented little more than “an animated punching bag.”

Gans did take the first two rounds to feel Sieger out but in the third he let loose with a violent attack and in essence, he never let up. “These blows seemed to take all the steam out of Sieger,” according to The New York Evening World, “for he weakened fast after that and was merely a punching ball for Gans.”

Keep in mind Sieger’s defeat of McFadden, just five weeks before.

“In the fourth round,” continued The American, “Gans made Seiger’s mouth bleed, and the hemorrhage [sic] was profuse for the balance of the fight, giving the scene that lurid glare of blood that adds to the aspect of the terrible.”

After the fourth, the fight took on the character of a mere slaughter as Gans battered Sieger around the ring mercilessly upon learning what would be the key characteristic of the fight: Sieger could not hurt him. He was gamely throwing punches but even the ones that breached the Gans defence did no harm. Gans was able to go about his work with a bloodless cool that is rarely seen in the prize ring, sure in his invincibility, able to bring forward his killing offence earlier than may otherwise have been the case. Keeping track of the knockdowns is not possible as the frequency with which Sieger was dropped confused eyewitnesses. Even Gans was astonished by Sieger’s performance, turning to Sieger’s manager Billy Roche and asking, “where did you get this fellow?”

“Gans sent his opponent to the mat a dozen times, landed over two-score of terrific right-hand blows on the jaw, yet Sieger always came to his feet ready and eager for the fray,” reported The Baltimore Morning Herald. “In fact, Gans became disgusted with himself several times. Once, when a right-hand hook on the jaw failed to send Sieger down, he scrutinized his glove as if to see if something was the matter.”

Gans set out showing a preference for the short left-hook that had got work done for him in so many fights but soon he added a long, lashing right-hand, his usual fondness for bodywork departed. In the tenth, Gans sent Sieger to the canvas three times and in the eleventh, the Kansas City Star counted “fourteen right swings on Sieger’s jaw.” The brutality of the assault almost beggared belief but Sieger, to his enormous credit, managed to mount some offence in the twelfth and thirteenth, for all that he was soundly beaten in both. Gans finally put him out of his misery in the fourteenth.

“His face smeared with blood,” testified The American, “trembling with faintness and yet the very personification of brute courage and pluck” Sieger finally found himself crawling upon his hands and knees, “feebly waving his arms and trying desperately to stagger to his feet to meet that awful mauling that Gans was giving him.”

Sieger’s corner belatedly threw up the sponge, protecting their charge from himself. Gans, as impressed as he had been during his short time as champion, “rushed” to Sieger’s corner and named him the gamest man he had ever met. Storied referee Charley White named Sieger the gamest fighter he had ever seen; a series of men with neither the courage nor the sufferance to draw the best from Gans had been supplanted by a challenger with neither the power nor the skill to compete, but the heart and the jaw and the sheer bloody-mindedness to force Gans to work.

Gans mercilessness impressed, but in truth Sieger’s gameness impressed more and as it was so shall it ever be. More than anything, his astonishing effort was a foil for Joe’s next title defence.

Game, too, was his next non-title opponent, Howard Wilson, who pulled himself repeatedly from the canvas before being rescued by his seconds in the third, just one month later. On New Year’s Eve Gans met Sieger again, over ten rounds and for the most part left him alone until the final third of the fight when he tried once more to put him away and failed, Sieger as determined in December as he had been a few weeks before. Gans had to settle for a draw, as agreed in the event of Sieger reaching the end. He leaves our story now; it is fitting that he does so having heard the final bell he had dreamed of, even if it was not in his one and only title-fight.

The very next day, in an arrangement we can scarcely believe in more modern times, Joe Gans was scheduled for a second fight, this one over the longer distance of twenty rounds against one Gus Gardner. Gardner, you may remember, was guilty of fighting scared in a confusion of a fight for which he weighed in at 138lbs. Fearful, and a failure in that he was blasted out in five, six round wins over the likes of Erne and McFadden helped keep him in position for a title shot against a Gans, who was bound to be at least slightly fatigued after ten rounds of tough sparring the day before. The draw, the dollar was everything in this era. If Gans could spin some quick cash matching a fighter who was chanceless in his ring, he would unashamedly take it, and somewhere there were trainers, managers and seconds who believed Gardner could somehow get the job done.

He could not get the job done.

“Gardner,” reported The New York World, “resorted to almost every foul trick he knew, except biting.” The Philadelphia man fought with no more bravery than he had in 1902, less, if that was possible. Gans, who was aided in his corner by Herford and by old foe Jack McCue, was clinched by Gardner “at every opportunity” and drew repeated warnings from the referee. By the eighth he was throwing himself to the canvas to avoid punishment. In the eleventh, having three times driven his knee into the lightweight champion, Gardner perpetrated upon Gans what can only be described as a rugby tackle, seizing him around the waist and throwing him forcibly to the floor. The thoroughly disgusted referee immediately awarded the fight to Gans.

“Cool and self-contained as an oyster the lightweight champion defended his title with the masterly skill of a champion ring general,” summarised the Baltimore Morning Herald. “There was no round of his battle with Gardner, in which Gans took the lesser honors, although he did not get strongly under way till after the fourth round…during the last four rounds Gardner took the count five times and landed barely a blow.”

Despite this miserable showing, Gardner was actually given an ovation as the tenth round ended and the eleventh began. Gardner was overwhelmingly expected to capitulate before the tenth was over and despite the fact that he tripped, pushed, grabbed and ran from Gans without trying to mount any offence, he was admired for making the eleventh. He was, at least, hissed and booed by the sixteen hundred in attendance as his clear plan to get himself disqualified once the eleventh was sighted was revealed.

Such were the trials and travails of the lightweight champion as 1903 dawned. In November of the previous year, Frank Erne had finally been eliminated by Jimmy Britt and all talk of a third fight between he and Gans was forestalled. Britt, meanwhile, in a strange and perverse twist, named himself the first “White Lightweight Champion.”

This was troublesome for Gans. First, Britt had stated publicly that he would not break the colour line under any circumstances, that he would not find occasion to match a fighter of African descent regardless of which title he might hold. This meant that he had a top contender who was not only actively avoiding him but who was also naming himself “champion.” Gans would have been only too aware that America of the early 1900s might find Britt the more palatable of the two champions, resulting in dollars being siphoned away from Gans and towards Britt as the two staged “defences.” As modern fans beguiled by as many as six champions in each division, we can sympathise.

In a wider sense though, Gans was on the rise-and-rise. Terry McGovern, with whom Gans had created so much confusion in 1900, was on the slide and for company at the very top of the fistic tree, Gans had only James J Jeffries, the rampant heavyweight champion who was approaching the peak of his powers and had eliminated pound-for-pound Mount Rushmore candidate Bob Fitzsimmons; the wonderful middleweight champion Tommy Ryan, who had suffered but one loss in the past six years, and that by disqualification; and The Barbados Demon Joe Walcott, who had started to lose but only to much larger men.

It was Gans though who stood atop what had been the best division at the end of the nineteenth century. While James Jeffries was every bit as imperious as Gans, he showed but a sliver of the skill the lightweight champion commanded, little of the defensive genius or gliding grace and while Jeffries was a superb general in the sense that he was able to impress himself and his fight upon almost any opponent, he did not have Joe’s brilliance in strategy.

My fondness for Gans may be causing me to call it early and those arguing for Jeffries or Ryan will get no strong opposition from me, but my guess is that in the same way Pernell Whitaker was considered pound-for-pound number one in 1993 and Roy Jones was considered pound-for-pound number one in 1996, Gans should be considered pound-for-pound number one in 1903. His genius in talent and thought gets him over the line.

Soon, welterweight and certain proof of his pound-for-pound credentials would call him, but for the moment Joe Gans remained a lightweight.

Check out more boxing news on video at the Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Book Review4 days ago

Book Review4 days agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoOleksandr Usyk Continues to Amaze; KOs Daniel Dubois in 5 One-Sided Rounds