Featured Articles

Every Joe Gans Lightweight Title Fight – Part 7: Steve Crosby

Color ought not to cut any figure in the ring so long as a man is willing to do his best. – Joe Gans

As 1903 got underway, Joe Gans showed the type of restlessness that only manifests itself in true pound-for-pound greats. The lightweight champion decided to pursue Philadelphia Jack O’Brien, who had recently scored a victory over future heavyweight champion of the world Marvin Hart, very nearly knocking him out. Gans proposed that in order to take the winner’s share of the purse he would only have to survive the distance but assured the press that he would seek to knock the bigger man out.

At first, from O’Brien, silence, then he cried off with an injured hand although he was well enough to be matched in late February and throughout March, including against Joe Choynski who had recently knocked out Jack Johnson. Joe Gans had been ducked by a man mixing it with elite heavyweights.

Frank Erne made some noises over a trilogy fight but did not back himself to the extent of placing a $1,000 side bet on the line, as Al Herford insisted. Herford, manager and general mouthpiece for Gans, insisted loudly that Joe would meet the “white lightweight champion” Jimmy Britt over twenty rounds and that in order to be named the world champion, all Britt had to do was hear the final bell.

“When I became a pugilist,” Britt responded, “I made a resolution not to meet colored men and I don’t intend to go back on it now.”

Gans was insistent.

“Britt has been saying that he could beat me and all that sort of thing…I am willing to make any concession he may desire. I am willing to let him name the date, weight, place of meeting and conditions as well as the percentage into which the purse will be split.”

From a champion, these are astonishing remarks.

This left a frustrated Gans without a big money fight. In the first decade of the twentieth century, however, there was always a serious contender to the lightweight crown to be repulsed. Gans, for his part, certainly was not about to draw any colour line.

Steve Crosby was a member of an African-American murderer’s row that duked it out for the role of foremost black lightweight contender through the late 1800s. He and Gans were no stranger to one another. They met for the first time in 1898, the winner to find himself in line for a shot at the era’s top fighters – the top white fighters. Gans controlled the fight with a flash of what would be his primed generalship, boxing left-handed and at distance, pumping his jab into Crosby’s gut. The Kentuckian was sickened by these shots and his seconds spared him the knockout blow, pulling him after six. The two fought a tame short-form fight in 1899 but for the main, Gans probably believed he had finished with Crosby, only for his rival to go eighteen fights unbeaten to force a third fight between the two.

This third fight, fought over twenty rounds, was key to their series and to Crosby’s plans for resisting Gans. Essentially, this involved his fighting like he was in a shorter fight, throwing caution windward and punches with it, trying to outland Gans in the early stages. This, he did but only with moderate success; Gans blocked, countered and chipped away at his opponent who by the tenth had begun a grim vigil of his own faculties, hanging on to Gans for dear life, trying to clinch his way to the final bell. Essentially Crosby was one of the last to take advantage of Joe’s one-time weakness, his inability to put away fighters bent only upon survival. Why this mattered so much more in 1901 than it does in 2021 is illustrated by this third fight. Crosby split the early part of the fight with Gans by modern eyes, but from the perspective of a good judge in this era, Crosby was amply rewarded for “forcing the fight.” When he erupted in the nineteenth and twentieth rounds in a savage attempt to rest the “colored” lightweight championship from Gans, Crosby probably had not won a round since the eighth or ninth, but the referee and sole arbiter was impressed enough to render a draw; Crosby had earned a rematch.

“Crosby showed,” noted a Washington newspaper in previewing that rematch “that he belonged in the first class of fighters.”

Gans won this fourth fight, fetching Crosby up against the ropes and shipping punishment into him when the police interfered to stop the prize-fight, not an uncommon occurrence at this time. In control at the time of the stoppage, Gans had been forced to wrest the fight from Crosby once again as he staged a repeat of his early attack. The result then, was unsatisfying. Crosby was not the first choice for a Gans defence, nor a second, nor a third, but he was a natural choice. As was his first defence against Elbows McFadden, Crosby represented unfinished business.

Gans arrived in Hot Springs, Arkansas, a whole week before the fight, unusual for him, and set straight to work. In this matter, Gans demonstrated a respect he did not replicate in his preparations for George McFadden, for example, illustrative perhaps of his sense that Crosby, in his heart and strength, might represent a potential banana-skin. Herford did not share this trepidation and loudly pursued wagers of $4,000 at odds and even money that Gans would dispose of Crosby within twelve rounds.

Crosby had already been in town for a month, and in fact had boxed a pair of slow draws with the former Gans victim Kid Ash in Hot Springs while waiting for the champion to arrive. These fights were only interesting in how uninteresting they were. Crosby, who might have expected to test himself in the early going for his presumed Gans strategy, instead clinched from the first, and throughout, before finishing each fight in a blazing attack.

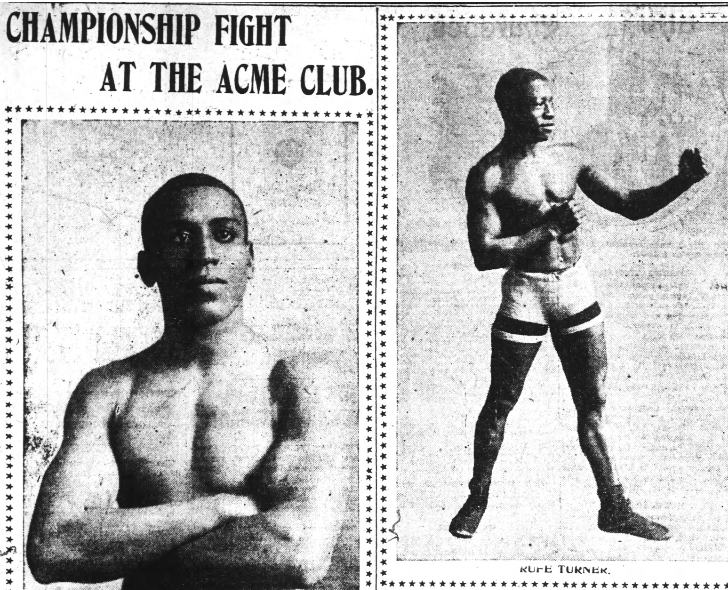

Previews concentrated on Crosby’s innate toughness and proven bravery in the ring, some reports perhaps continuing to aim barbs at Gans in naming Crosby “without doubt the toughest colored lightweight in the business.” He was not expected to beat Gans, but the papers, like the champion, expected a good show from the challenger.

Both men hit their mark upon the scales at 3pm and around six hours later made their way to a ring stuffed with intrigue.

The referee was none other than Tommy Ryan. Gans would share the ring with the middleweight champion and perhaps the only man in the world that could rival him for skill. Seconding Crosby was a figure from Joe’s future, the most significant foe from the second half of his title reign, Oscar Nielsen, ring name “Battling Nelson.” Even the timekeeper was a person of interest, superfan and professional gambler “Honest” John Kelly responsible for sounding the gong. Before the largest crowd ever assembled at Hot Springs Athletic Club, Crosby greeted the gong with a clinch.

Despite having had some success against Gans early in two fights, his whole outlook had changed. Whether he was intimidated, whether he felt something he didn’t like in the first exchanges or whether his dramatic change of strategy was part of some bold plan to stop Gans late, Crosby was warned by Ryan as early as the second round. Gans, who had begun with a certain caution, perhaps expecting the traditional rush from Crosby, stuck his left in his challenger’s face repeatedly but waited; when it became apparent that there would be no rush, but rather a persistent commitment to single right hands, Gans began to impose himself.

Crosby “seemed afraid to mix it up” according to the St. Louis Republic, the Richmond Times Dispatch adding that his “hugging tactics” were what “saved him from early defeat” although the audience joined Tommy Ryan in loudly objecting. There is something a little unfair about this. Crosby did not deliver on an early attack, and his constant clinching obviously frustrated the crowd, but he crossed the ring to meet Gans at every bell. He did not run; but upon closing the distance he did everything he could to avoid being hit, at the expense of his own offence.

“In the third, fourth, fifth and sixth rounds,” reported the Daily Northwestern, “Gans did most of the fighting, Crosby continually clinching and hugging in a manner that disgusted the spectators.”

I will spare the reader a detailed description of what occurred in these turgid rounds, but I suspect that Gans was more than satisfied with what transpired. There was none of the hot fighting seen in their earlier contests and he was being allowed to chip away at Crosby’s resistance at almost no cost to himself. Crosby was gifting the type of control that Gans often had to fight for, though he had learned to consistently achieve it.

In the seventh, Crosby’s clinching failed as Gans went to work on him as he tried to close and clinch, Gans risking more for a higher return against an opponent who had been punished. In the eighth, Gans stepped in with a long left uppercut, using Crosby’s own momentum against him, driving him not just off his feet, but through the ropes, “a distance of some four feet” as observed by the Louisville Courier-Journal.

“The blow was hard enough to have defeated the average heavyweight,” continued the paper, “but Steve quickly arose, vaulted over the ropes, and rushed Gans to his corner.”

The Courier-Journal was perhaps alone in admiring Crosby’s performance so completely, and in fact it led them to name him “outside of Gans” no less than the “toughest proposition in the lightweight division.” This is quite a claim. Still, they found column inches too to describe Joe’s brilliant footwork and consistent control of distance which prevented the development of whatever plan Crosby and his people had concocted. After being ditched to the auditorium floor in the eighth, Crosby’s shot at the title was essentially over.

The Gans jabs “were too much for Crosby, and [he] began to show signs of weakening in the ninth round” according to the New York Evening World, while the St. Louis Republic went a little farther; for them, Crosby was now looking for a way out. That seems spurious; if Crosby wanted to quit, there were ample opportunities in the eleventh. Gans, as he so often looked to do once his opponent was under control, feinted with the left and looked for the right. Crosby bought the feint and kissed the right, dropped clean, but he fought his way to his feet rather than sit out the count.

The Evening World: “[Crosby] got up and was sent down again by a similar blow. Crosby was weak, but at the count of nine managed to stagger to his feet. Gans nailed him again on the jaw with his right and he went to the floor in a heap.”

Still, Crosby would not quit but as he wrestled with the count, and with himself, his corner tossed up the sponge. There is some disagreement as to whether or not Ryan “accepted” the corner’s instructions and that he had rather ignored it and waved for the two to fight on as Crosby tottered to his feet. This does make some sense, as Ryan was involved in some of the most vicious encounters in ring history, but either way, Crosby never made it out of the eleventh. Gans had successfully defended his title once more, tricking, trapping and out-fighting Crosby on the inside, the only man up until that point who had stopped the heart-fuelled Crosby with punches.

Gans returned to Baltimore, where local papers reported him “unscratched” and a little piqued that he had taken so long to stop Crosby. Gans had not appreciated Crosby’s clinching. Herford, pleased to have won his bet that the fight would be settled before the end of the twelfth but put out that he had been able to lay only hundreds rather than thousands, went east to prepare the way for Joe’s next match, a non-title fight with two-time victim Jack Bennett, a talented fighter with a soft chin. Gans blasted Bennett out in five on this occasion.

But the same old problem persisted. Gans could not make big fights. Spike Robson made noises but could not deliver in the ring; he was eliminated from contention not once but several times. Yet again, the prospect of a third fight with Frank Erne emerged, but to no end. After dusting Australian welterweight Tom Tracey, Gans made it clear that he was bound for the division above where perhaps the big fights could be made. Even at the higher poundage, expectations were that Gans would dominate the opposition, a task that “ought not to be particularly hard” for him according to The Republic.

After crushing the popular Willie Fitzgerald in ten – more about this fight next time – and a hapless Buddy King in July, Gans went quiet for three months, something that had not happened since his 1899 knockout by Elbows McFadden. There was talk of a trip to England, talk of a bout with Willie Lewis, or welterweight Martin Duffy; instead there was nothing. It seemed Jimmy Britt might finally dare to break the colour line, but only if the champion Joe Gans would agree to make 133lbs at ringside.

When Gans returned it was in an old-fashioned barn-burning tour, six fights in fifty days, all but one over a short distance. Results were poor. These were six-round, no-contest results and in truth, were of little import insofar as Gans wasn’t knocked out; but when he lost over fifteen rounds to a teenager named Sam Langford, it was clear that Gans had over-reached. This was not a close fight: Langford, arguably the greatest fighter in history in full bloom, was then barely a novice. He out-thought and out-fought Gans, a disturbing way for a great general to lose.

But what was Gans doing fighting Langford just hours and three-hundred miles after he had fought no less a figure than Dave Holly? This was 1903; the schedule that saw him fight in Philadelphia on the seventh of December and Boston on the eight was an absurdity. Gans, the ultimate professional, seemed to have contracted a dose of cowboy. Unchallenged as a lightweight since he crushed Erne in one, he sought challenges perhaps no man could have met. Carrying a stomach injury to the ring against Langford and finding himself soundly beaten, when Gans took to the ring to defend his title just thirty-five days later he seemed something he had not been since the 1800s.

Vulnerable.

Check out more boxing news on video at the Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Book Review2 weeks ago

Book Review2 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles6 days ago

Featured Articles6 days agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRahaman Ali (1943-2025)

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoTop Rank Boxing is in Limbo, but that Hasn’t Benched Robert Garcia’s Up-and-Comers