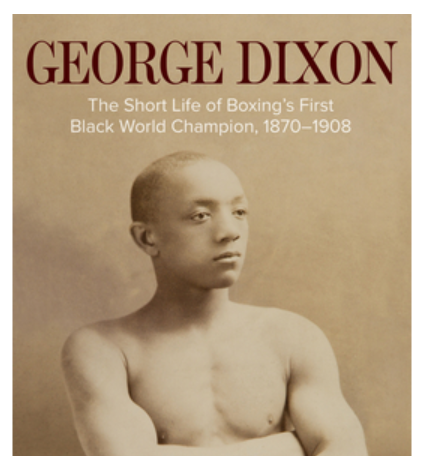

Book Review

Literary Notes: “George Dixon” by Jason Winders

BOOK REVIEW by THOMAS HAUSER — George Dixon was boxing’s first Black world champion.

“For a decade leading into the twentieth century,” Jason Winders writes, “few Black men were as wealthy and none were more famous. To a Black culture cementing its first national heroes, Dixon was the single-most significant athlete of nineteenth-century America. He fought constantly as a professional – maybe against a thousand opponents in his lifetime. While most were exhibitions against rather faceless foes, a hundred or so of those bouts were chronicled by both Black and white presses. A half dozen came to define an era.”

In George Dixon: The Short Life of Boxing’s First Black World Champion, 1870-1908 (University of Arkansas Press), Winders gives readers a well-researched, well-written, entertaining account of this remarkable man.

Dixon was born on the outskirts of Halifax, Nova Scotia, on July 29, 1870. Quite possibly, one of his grandfathers was white. Sometime in the 1880s, the Dixon family moved to Boston.

Dixon fought his first fight at age sixteen. Writing about him one year later, Winder notes, “He was just a kid. Thin lead weights slid into his shoes between his bare feet and leather soles so he could climb above one hundred pounds and legally be allowed to compete. He had the body of a boy – thin, gangly, with arms slightly longer than his diminutive frame should have allowed. At first, he fought at 108 pounds. As the years went by, he developed into a genuine bantamweight and fought at 112 pounds. Then he went up to 116 pounds, then to 118, and then to 122, all apparently without suffering any loss of skill.”

There are few visual images of Dixon in combat. Contemporaneous written accounts suggest that, at his peak, he had remarkable defensive skills, excellent timing, superb footwork, an uncommon ability to judge distance, and an educated left hand. He was blessed with courage, patience, the ability to endure punishment, and an iron will. His training regimen was sophisticated for its time.

A handful of fights were of particular importance in Dixon’s storied ring career. On June 27, 1890, having journeyed across the Atlantic Ocean, he knocked out British bantamweight and featherweight champion Nunc Wallace in Soho, England. That raised his profile exponentially. Nine months later in upstate New York, Dixon knocked out Cal McCarthy in a rematch of an 1890 draw to claim to the American portion of the featherweight crown. Then, on July 28, 1891, in San Francisco, he knocked out Australian bantamweight champion Abe Willis.

“His bout against Willis,” Winders writes, “would solidify Dixon as the greatest fighter – not just Black fighter – of his division in the world. With this victory over Willis, George Dixon became the undisputed world bantamweight champion, the first Black man to earn a world boxing title. And it all happened before his twenty-first birthday.”

Then, for good measure, Dixon knocked out the newly-crowned British featherweight champion Fred Johnson in Brooklyn on June 27, 1892. That further solidified his kingdom.

These triumphs came at a time when boxing was becoming ingrained in America’s national consciousness. The Police Gazette, with a weekly circulation that ran as high as 400,000 copies, was America’s most popular tabloid magazine. Editor Richard K. Fox relied heavily on the sweet science to sell the publication. In 1889, roughly sixty percent of its headlines dealt with boxing. Now, with Dixon at his fighting peak, the Police Gazette called him “the greatest fighter – big or little – the prize ring has ever known.”

Winders puts the importance of those words in context: “Perhaps today we read over words like ‘slave’ and ‘master’ too easily. But the mindset that fueled centuries of this thinking did not die with the stroke of the Great Emancipator’s pen. It was deeply embedded in American culture. Just a generation before the Dixons arrived in the United States, the Black body was nothing more than a tool of labor, an expensive shovel or plow horse used and abused by a white master. Now a Black man was asserting his manhood by way of sport, beating white men with his near-bare hands, rising to heights higher than any man his size no matter what color. Dixon stood as champion, inspiration, among the wealthiest and best-known men in the country. More than a fighter, Dixon came to represent hope.”

That said; in truth, Dixon regarded his celebrity standing as belonging more to himself than to Black America. “In the ring,” Winders writes, “he was a hero to the Black man. But he lived in a white world rather contentedly.” Dixon’s manager, Tom O’Rourke (who took half of Dixon’s earnings) was white. Dixon was married to O’Rourke’s sister. Dixon was widely admired for his ring skills. But equally important to the narrative, he was not regarded as a threat. “Much of his widespread acceptance,” Winders notes, “hinged on his smaller-than-normal stature.” And despite being married to a white woman, he had always “known his place” in society. Tom O’Rourke, Winder recounts, was often “quick to make mention of that in the press.”

In all his research, Winders was able to find only one instance in which Dixon was reported as speaking publicly about his meaning to Black America.

On May 22, 1891, Dixon was honored at the Full Moon Club in Boston’s West End, the center of the city’s Black community. Speaking to an audience of mostly young Black men, he declared, “I have always tried to do my duty. I have never yet entered the ring but that I was conscious that I was not only fighting the battle for myself alone, but also for the race. I felt that, if I won, not only credit would be given to me, but that my race would also rise in the estimation of the public.”

“This moment,” Winders observes, “among the thousands of mentions of Dixon in the press of the day, is an outlier. Never again in the reporting did he speak about a ‘duty’ to his race. Certainly, his actions in the years that followed were not in line with what Black America expected – or needed – from him. Never political or bombastic, rarely confrontational or rebel-rousing, Dixon never embraced his race duty more publicly than this moment.”

In September 1892, Dixon further solidified his importance when he participated in a historic three-day fight festival called The Carnival of Champions at The Olympic Club in New Orleans.

On September 5, Jack McAuliffe knocked out Billy Myer to retain the world lightweight crown. More famously, on September 7, James J. Corbett dethroned John L. Sullivan to claim the heavyweight championship of the world. In between these two fights – On September 6 – Dixon defended his world featherweight crown against Jack Skelly.

Prior to the Civil War, New Orleans had been the slave trading capital of the United States. Now, a Black man and a white man were exchanging blows there. And the battle was waged before spectators of both colors.

“Among the earliest arrivals for the Skelly-Dixon bout,” Winders writes, “were Black spectators for whom a large section on one of the upper general admissions stands had been set apart. It was a first for the club – an amazing sight in the heart of the former Confederacy. Among the crowd of two hundred Black men were prominent politicians and regular men lucky enough to snag a ticket. Five thousand people had filled the arena. City councilman Charles Dickson, a prominent member of the Olympic Club, welcomed Dixon into the ring and then warned the crowd that the upcoming contest was between a Black man and a white man in which fair play would govern and the best man win.”

Dixon knocked out Skelly in eight rounds. His fame and the adulation for him would never peak that high again.

The Carnival of Champions showcased Dixon in a way that he hadn’t been showcased before. “Until that moment in New Orleans in September 1892,” Winders observes, “Dixon was an insulated fighter. Then he landed in the middle of forces already in motion, forces still lingering from the after-effects of slavery and the Civil War. All of those forces would gain strength that summer and continue through Dixon’s lifetime as societal forces shifted to a more aggressive approach toward limiting Black opportunity. Shielded from those forces for years, Dixon would soon experience them head-on without the protection of the white world in which he inhabited. The Carnival of Champions was not a moment when George Dixon changed the world. It was the moment when Dixon left his sheltered existence and became part of it.”

“Immediately after the Dixon-Skelly bout,” Winders reports, “Olympic Club members regretted pairing the two.” Olympic Club president Charles Noel publicly stated, “The fight has shown one thing, however, that events in which colored men figure are distasteful to the membership of the club. After the fight, so many of the members took a stand against the admission of colored men into the ring as contestants against white pugilists that we have pretty well arrived at the conclusion not to give any more such battles. No, there will be no more colored men fighting before our club. That is a settled fact.”

In the same vein, following Dixon-Skelly, the New Orleans States editorialized that there was “inherent sinfulness” to interracial fights and complained that “thousands of vicious and ignorant negroes regard the victory of Dixon over Skelly as ample proof that the negro is equal and superior to the white man.”

Meanwhile, as the forces of repression were pushing back against gains made by Black Americans during the Reconstruction Era following the Civil War, Dixon’s ring skills were eroding. In addition to competing in official bouts, he was fighting in hundreds upon hundreds of exhibitions as part of traveling vaudeville shows.

“In advance of the troupe arriving in town,” Winders recounts, “a notice was posted that fifty dollars would be given to any person who could stand up before Dixon for four rounds. During these engagements, Dixon met all comers and often fought fifteen men irrespective of size in the same night – an immeasurable toll on his small frame.” A newspaper in West Virginia noted, “Dixon is meeting too many lads in his variety show act. His hands cannot certainly be kept in good condition with such work. He has used them so much in these four-round bouts that they are no longer the weapons they were.”

As for official fights, Winders reports, “Noticeable cracks in Dixon’s once spotless technique were developing. Dixon’s speed was waning. His punches were no longer beating his opponent’s attempts to block. His grunts were louder and more emphatic as blows that would once find empty space were now landing squarely on his face.”

Lifestyle issues were also becoming a problem. Again, Winders sets the scene:

“When it came to New York City at the turn of the twentieth century, Manhattan’s Black Bohemia embodied the newer and more daring phases of Negro life. On these streets, visitors found a lively mix of vice and vitality with clubs packed nightly with free-spending sporting and theatrical people, as well as those hoping to catch a glimpse of those famous patrons. The area had become a national symbol of urban depravity, noted mainly for its gambling houses, saloons, brothels, shady hotels, and dance halls that stayed open all night. And while few boxers of this period were residents of New York City, they all found their way to Black Bohemia. Dixon began to frequent Black Bohemia and, by the time he became a regular, he was bleeding money into the district’s many establishments. The ponies got some; George couldn’t resist craps; and then there was booze to be bought at high prices for everybody. And he drank. Dixon would tear off $5,000 as his share of a win and it would disappear, one way or another, in a few days.”

“Dixon got rid of his money faster than any fighter I ever knew, except myself,” John L. Sullivan noted.

Dixon lost his featherweight title to Solly Smith in 1897 but regained it the following year. Then, on January 9, 1900, he fought Terry McGovern at the Broadway Athletic Club in New York. McGovern administered a brutal beating. The fight was stopped by Dixon’s corner in the eighth round.

“I was outfought by McGovern from the end of the third round,” Dixon acknowledged afterward. “The blows to my stomach and over my kidneys were harder than any I ever received. I entered the ring as confident as ever, but after going a short distance, I discovered that I was not the Dixon of old. My blows, although landing flush on my opponent, had no effect.”

After Dixon-McGovern, The Plaindealer (a Black newspaper in Topeka, Kansas) editorialized, ” The race has no gladiator now to represent it. We are in darkness, for Dixon’s light has been put out.”

On March 30, 1900, less than three months after losing to McGovern, Dixon opened a saloon called the White Elephant in the heart of the Tenderloin District. He was a poor business manager and his own best customer. Prior to fighting McGovern, he’d said that the McGovern fight would be his last. It wasn’t.

The White Elephant failed and Dixon kept fighting. Over the next six years, he engaged in 77 official bouts, the last of them on December 10, 1906. According to BoxRec.com, he won only thirteen of these encounters. Overall, BoxRec.com credits him with having participated in 155 recognized boxing matches with a final ring record of 68 wins, 30 losses, and 57 draws. In Dixon’s era, when a fight went the distance, there was often no declaration of a winner.

Meanwhile, Dixon began drinking more heavily. As Winders writes, “He increasingly celebrated his victories with or drowned his troubles in alcohol. That led to numerous confrontations with police. His personal demons were clashing with public sentiment toward Blacks in the wider society. His celebrity no longer shielded him. In public, he was prone to violent outbursts and fits of rage. In private, he was beholden to his own dark vices. Few Black men were as pitied, and none named more frequently from public square and pulpit as a cautionary tale of modern excesses.”

In due course, Joe Gans succeeded Dixon as the most famous and successful Black boxer in the world. After defeating Battling Nelson on September 3, 1906, Gans made a show of publicly offering Dixon a job as head bartender at a hotel that he owned in Baltimore. But the job never materialized.

“I never heard anything from Joe about going to Baltimore,” Dixon said later. “I guess he was advertising his show when he said that. But his hotel would sure look good to me right now”

“It isn’t what you used to be,” Dixon told an interviewer. “It’s what you are today. The men who followed me in the days of prosperity can’t see me when I am close enough to speak to them.”

On January 4, 1908, Dixon was admitted to Bellevue Hospital in New York.

“He was wasted and worn,” Winders writes. “To the doctors, he famously said he had ‘fought his last fight with John Barleycorn and had been beaten.’ His condition became worse and continued sinking. He died at 2 p.m. on January 6, 1908. He was thirty-seven years old. His funeral service in Boston was the largest funeral gathering for a Black man in the history of the city.”

Winders has done an admirable job of recounting George Dixon’s life. He places people and events within the context of their times and brings names in dusty old record books to life. He writes well, which is a prerequisite for any good book; does his best to separate fact from fiction; and is sensitive to the nuances of his subject. He also avoids the pitfall of describing fight after fight after fight, focusing instead on the ones that mattered most. Readers are transported back in time to the Olympic Club in New Orleans for the three-day Carnival of Champions in 1992. Dixon’s sad beating at the hands of Terry McGovern in New York in 1900 is particularly well told.

Winders also performs a service by stripping away the myth of Nat Fleischer as a reliable boxing historian.

“Much of Dixon’s story,” Winders writes, “has been left in the hands of Fleischer. Although he is an icon to many, not all are enamored by Fleischer’s ability to recount the past. His research and record keeping leave much to be desired. His biographies and record books are rife with errors.”

Winders then approvingly quotes historian Kevin R. Smith, who labeled Fleischer’s best-known writing about Black boxers (the five-volume Black Dynamite series) as “heavily flawed,” called some of his other offerings “downright ludicrous,” and declared that Fleischer was “unabashed in his use of poetic license, making up sources and fictionalizing events when unable to unearth the true facts.”

Less than a year after Dixon died, Jack Johnson journeyed to Australia and dethroned Tommy Burns to become the first Black man universally recognized as heavyweight champion of the world. “Historians want to start with Johnson,” Winders writes, looking back on that moment. “But why not Dixon? By ignoring him, we have lost the point where the story of the modern Black athlete in America begins.”

One reason many chroniclers start with Johnson is that so little about Dixon is known. “Historians,” Winders acknowledges, “have placed Dixon at the forefront of boxing pioneers, but they often don’t seem to know why beyond a few lines related to his ring resume. Outside of some isolated examples, sport history – indeed, Black history – rarely celebrates his accomplishments. There is an odd silence in his isolation. Dixon sits tantalizingly, even frustratingly, close to us – just over a century ago. Surely, his life should be too recent to be lost to time.”

Winders has done his part – and then some – to save us from that loss. George Dixon: The Short Life of Boxing’s First Black World Champion, 1870-1908 is as good a biography of Dixon and portrait of boxing in that era as one is likely to find.

Thomas Hauser’s email address is thomashauserwriter@gmail.com. His next book – Broken Dreams: Another Year Inside Boxing – will be published this autumn by the University of Arkansas Press. In 2004, the Boxing Writers Association of America honored Hauser with the Nat Fleischer Award for career excellence in boxing journalism. In 2019, he was selected for boxing’s highest honor – induction into the International Boxing Hall of Fame.

Check out more boxing news on video at the Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Book Review3 weeks ago

Book Review3 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoThe Hauser Report: Debunking Two Myths and Other Notes

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRahaman Ali (1943-2025)

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoTop Rank Boxing is in Limbo, but that Hasn’t Benched Robert Garcia’s Up-and-Comers

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoKotari and Urakawa – Two Fatalities on the Same Card in Japan: Boxing’s Darkest Day