Featured Articles

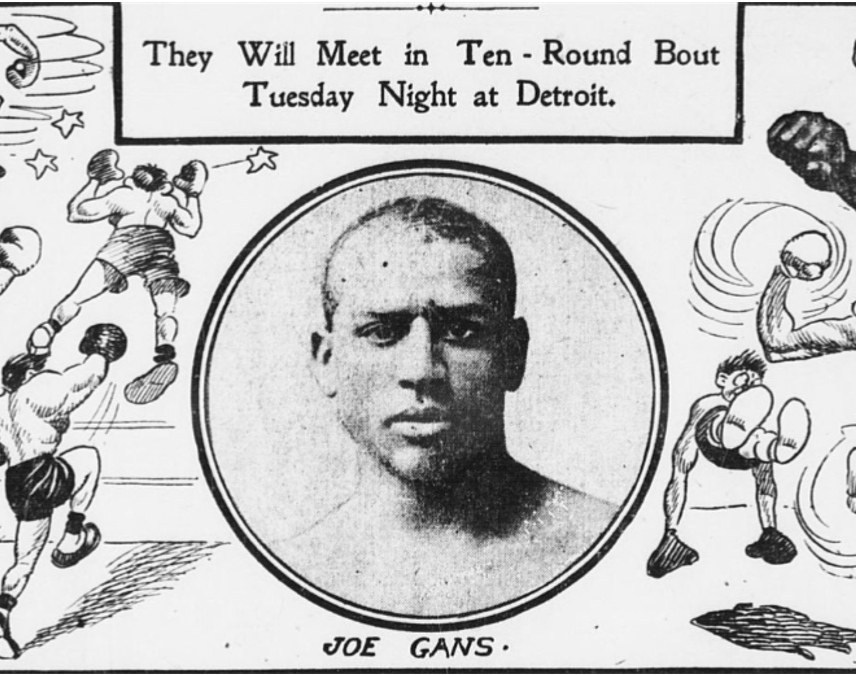

Every Joe Gans Lightweight Title Fight – Part 8: Willie Fitzgerald

Gans is a wonderful fighter, but his showing in his fights during the last five months indicates that he has gone back to some extent. – The New York Evening World, January 9th, 1904.

A fighter’s prime is a thing of tentative certainty. Whether or not a fighter remains “prime” is a debate that rages on internet messaging boards, twitter and among gamblers in perpetuity – whether a fighter remains within the range of his very best as a boxer is among the most important factors in determining both the future and the past in all matters fistic.

This is because it is not just a matter of predicting the fight or remaining a gambler in the black, but a matter of proper historical contextualisation. Instinctively, we understand that this matters, this is why you never hear people shouting about the ease with which Larry Holmes defeated Muhammad Ali, or with which Rocky Marciano defeated Joe Louis.

Each fighter is different, and each fighter’s prime is different, which is why deciphering it can be so difficult, but if we take a modern great like Manny Pacquiao, we probably see his very best years as being from 2006 when he legitimately got his weaker hand working, to his desperately close fight with Juan Manuel Marquez in 2008 when his calves started to bother him. Boxing is complex. It took eleven years for Pacquiao to reach his technical summit and when he did, he had but twenty-seven short months in which to enjoy it before his body began to betray him.

Every fighter is different, because every fighter relies upon technical acumen, physical capability and experience to a different degree. Bernard Hopkins at his best knows angles, distance and timing as well as any fighter of the last fifty years, and so his prime landed late, as he took advantage of experience to season his expertise. Roy Jones, on the other hand, peaked earlier and dipped off more dramatically because the fountain of his greatness was speed. Pacquiao required a glorious blend. What of Joe Gans?

Gans is not unusual in that he became his best self the day he picked up his title. In the past seven instalments, I hope I have managed to trace Gans from incomplete contender to dominant world-champion, a man whose experience bought him generalship to match his physical gifts and technical acumen. For Gans, make no mistake, was as much Bernard Hopkins as Roy Jones and in this, more like Manny Pacquiao in arc than either. The difference: Gans fought more often and over longer distances than any of them. In the first year of his prime, Pacquiao managed twenty-nine rounds, a lot for an elite fighter this century; Gans, despite winning mostly by knockout, fought a hundred in his. The wear and tear on even a genius like Gans was significant.

It is little wonder then that in the winter of 1903, talk began to turn to Joe Gans having “gone back.” He had by this time been in his prime nearly as many months as Manny Pacquiao would remain in his more than a hundred years later.

So, when he emerged from the breakneck barnburning tour which followed his longest break since he became champion, having suffered indifferent results and even a defeat, questions manifested for the first time since he ended Frank Erne’s championship reign. His next title opponent, in early January 1904, was to be Willie Fitzgerald, an Irishman who had relocated to New York City in pursuit of the riches the new pugilism enjoyed.

Fitzgerald was real. His career had brought him victories over Mike Sullivan, Charley Seiger and Gus Gardner; in April of 1903, he had been matched with the uncomfortably titled “white” lightweight champion and perpetual drawer of the colour-line, Jimmy Britt.

Fitzgerald seemed for a moment on the verge of a genuine upset when he dropped Britt in the final minute of the very first round. Appearing both bigger and stronger, Fitzgerald cut a figure standing over his more prestigious foe; in truth though, Britt was for the most part unharmed. Fitzgerald put a minor hurting on the world’s number one lightweight contender in the twentieth and final round, but in between, Britt was the man in control. He consistently targeted Fitzgerald’s gut and torso with what amounted to lightweight’s finest body attack. Fitzgerald dropped an uncontroversial points loss but Britt was impressed.

“He is a better man than Frank Erne,” he claimed. “He can take a punch and go the pace at a greater speed.”

Now things complicate themselves a little so I’m going to restate the timeline:

In April of 1903, Jimmy Britt defeated Fitzgerald over twenty rounds. Just before this, Gans had fought a title-fight with Steve Crosby, winning in eleven. The rest of 1903 was relatively quiet for Gans and included that three-month layoff before boxing that barnburning tour that included his most indifferent work post his title win. In January of 1904 he was to be matched with Fitzgerald.

However, before his three-month break but after he defeated Crosby, before he dropped points losses to welterweights Jack Blackburn and Sam Langford, Gans met Fitzgerald for a first time.

This is an intriguing move on the part of Joe Gans. As we discussed in Part 6, Britt’s anointing himself the “white lightweight champion” was problematic for Gans. It offered the public a choice in champions, and it was very possible that the public might conclude that Britt was to be preferred. Further muddying the waters was Britt’s outright refusal to meet the true champion on the grounds of his race. So just four weeks after the Britt fight, Gans met Fitzgerald on a clear mission to do what the white champion had been unable to do: stop him inside the distance.

On May 29th, 1903 on Britt’s turf in San Francisco, Gans did just that, taking Fitzgerald out in ten rounds having failed to make weight for what was billed in some quarters as a title fight. No titles were going to change hands with the champion weighing in at just under 140lbs though, and the first real sign of indiscipline on the part of the champion manifested. Not in the ring though. He took the unsporting advantage and turned it into perhaps the most beautiful knockout of his career.

The San Francisco Call described “A jolty left which travelled but a few inches…Gans landed [the short left] then a right to the jaw with the precision and power of a steam hammer, turning Fitzgerald completely around.”

Fitzgerald then “sank slowly to his knees and then lay prone on the matt” while ten was intoned over his still form.

The press were besides themselves in praise for this performance. Gans was a “wonder” who fought “aggressively throughout” although “all styles of going seemed to suit him.”

Gans had the result he wanted, and it was straight up reported that Fitzgerald had been less impressive against Gans than he had been against Britt. Britt was piqued. Surrounded by pressmen he repeatedly stated that he felt Gans would not be able to land upon him as he had Fitzgerald and, eventually, yes, he would meet the champion but only if Gans would agree to make 133lbs.

Gans then, had succeeded in baiting Britt into a commitment, for all that it called for Gans to make a weight he did not favour. Furthermore, he had proven himself ahead of Britt insofar as the wider lightweight field went; referee Eddie Graney named Gans “in a class of his own.” This opinion was echoed behind this fight.

It is worth noting down Joe’s own opinion on the fight, summarised here from several different accounts:

“There was never a time in the fight I thought I would lose…He can hit hard with either glove and I was there to prevent his glove landing on my jaw…He did not hurt me at any stage of the battle…I did not find him hard to hit.”

This then, was the problem Gans had when it came to his first defence of 1904: he had already proven himself the direct superior to his challenger. Not three years before – months before. It underlined the problem a fighter of Joe’s class was faced with, how to find challenges on a landscape he had scorched free of all resistance. It was little wonder, perhaps, that his interest had begun to wane.

The fight was made at 135lbs at the Light Guard Armory, Detroit, on January 12th, 1904. To the satisfaction of nobody, the fight was to be staged over ten rounds which was all that the law then permitted in these parts.

Gans stalked into Detroit on the 4th; he seemed in no mood, maintaining silence while eager Detroit pressmen peppered him with questions. “He says little,” reported The Detroit Free Press, “leaving his manager to do the talking…in street attire Gans does not look like a lightweight. On close inspection, however, one can note his strong build.” The following day, Gans was in training, sparring a local middleweight at the Media Baths. Fitzgerald, meanwhile, set up at Cameron Cottage, accompanied by the famed Italian Iron Man Joe Grim who appeared to be coaching him as well as feeding him copious servings of spaghetti which he insisted reduced his chances of being knocked out. Harry Tuthill, who trained Young Corbett, arrived a few days later to finish up his training.

It snowed that week, the temperature dropping as far as fourteen degrees below zero; Gans took to the road, putting in five miles every day, not excessive but enough to keep him well in sight of 135lbs. For his part, and despite the preponderance of pasta in his diet, Fitzgerald curtailed his training on the seventh, finding himself below the required weight and a little sore from apparent over-training. Gans trained publicly that same day, impressing onlookers with the quickness of his work. There seemed indecision as to whether his “eastern critics” were off the mark in suggesting his decline was at hand, but it is equally clear that many of the Detroit newspapermen were seeing the champion in the flesh for the first time.

Both training camps proceeded efficiently and both men impressed the locals so the line was unmoved by fight night with Joe Gans a 2-1 favourite. This sent Al Herford charging about town offering to bet five-hundred dollars that Gans would win and five hundred dollars that he would do so within the ten scheduled rounds. It is strange to hear of a fighter’s organisation barrelling around during fight week looking for takers but not only was this normal but it was also freely reported by a cheerful press, whose offices were sometimes even the site of large-stake exchanges. Whether or not Herford found a home for his money is unrecorded, but it is known that if he made his bet on Gans inside the distance, he lost that money.

Gans, who hit his mark at the 6pm weigh in with ease, took control of the fight early in a way that must have seemed familiar to both he and Fitzgerald. His specific method was a short left jab to the face, a punch that must have looked dangerous to Fitzgerald given what happened to him in San Francisco, followed by a right hand to the body. It sounds simple, like something an experienced pugilist like Fitzgerald should have been able to solve, but these two punches worked as counters to almost any shot Fitzgerald could muster. “Confidently the aggressor,” reported The Free Press, “he followed the Brooklyn boy about the ring, the latter showing that he feared Gans in every exchange and frequently covering up and allowing the champion to punch at him at will.”

These words will now be familiar to readers of this series, another Gans opponent, another man passive with fear, another easy evening for the great champion. Surely this suggests to all that Gans remained in his prime? It certainly is possible. After flashing Fitzgerald to the canvas in the first with a left hook, Gans spent most of the first half of the fight in complete control. The fight was slow, but in every exchange Gans had the last word, sometimes doubling up with rights to the body. Fitzgerald was criticised for underusing his right hand in the early going, but it is a fact that Gans countered this punch mercilessly, dropping him off a right hand in the fourth.

At the bell to end the fifth though, the two were “swinging wild at the gong” according to The Philadelphia Inquirer, which had Fitzgerald frantically giving way after sucking up a Gans right-uppercut but continuing to fight even as he broke ground. Fitzgerald was dropped again in the eighth, either by a left-hand to the jaw or bundled over underneath that punch in something more akin to a slip; after eight he had yet to win a round on most ringside cards, but in the ninth, something changed.

The round started as any other, Fitzgerald landing meaningless, light punches, Gans landing hurtful ones, staggering his man with one chopping right, but instead of moving back, Fitzgerald closed and landed either three or four hard left hands to the body and a left hand to the jaw. Gans, caught out by an unexpected charge, shipped these punches and immediately began showing signs of distress. The bell spared him further punishment.

According to the Detroit Free Press, Gans returned to his corner “vomiting.” This was reported elsewhere, The Washington Times claiming “Gans went to his corner vomiting and to a certain extent in distress.” This then was the greatest crisis Joe’s ring career had suffered since Erne opened the finishing cut upon him in his very first title fight; he toed the line for the tenth with gritted teeth.

Champions are champions and despite the heavy punches he absorbed in the ninth, Gans contested the tenth. My sense though is that Fitzgerald took it away from him at the bell, The Free Press reporting a “straight left to Gans’s face and right to head and left to body and crosses right to jaw” to punctuate the round.

The Chicago Tribune was unimpressed with Gans, noting that “the champion is backing up” and was “in distress at the final gong, and had the contest been fifteen rounds instead of ten, he would have left the ring a beaten man.”

This is debatable, obviously, and based on the punishment Gans had dished out and the closeness of the tenth my suspicion is that he would have re-emerged as the general, but it is not possible to find this type of criticism of Gans in a title fight before the Fitzgerald rematch.

This was inconvenient for the champion. His greatest challenges, and the fights that would come to define him, still lay ahead, including the fight he most wanted. Joe’s next title defence would be against Jimmy Britt.

Check out more boxing news on video at the Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Book Review2 weeks ago

Book Review2 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles6 days ago

Featured Articles6 days agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRahaman Ali (1943-2025)

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoTop Rank Boxing is in Limbo, but that Hasn’t Benched Robert Garcia’s Up-and-Comers