Featured Articles

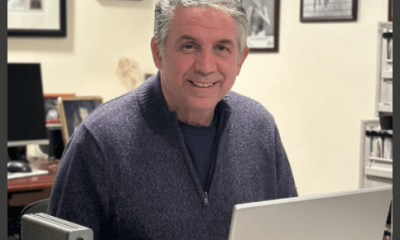

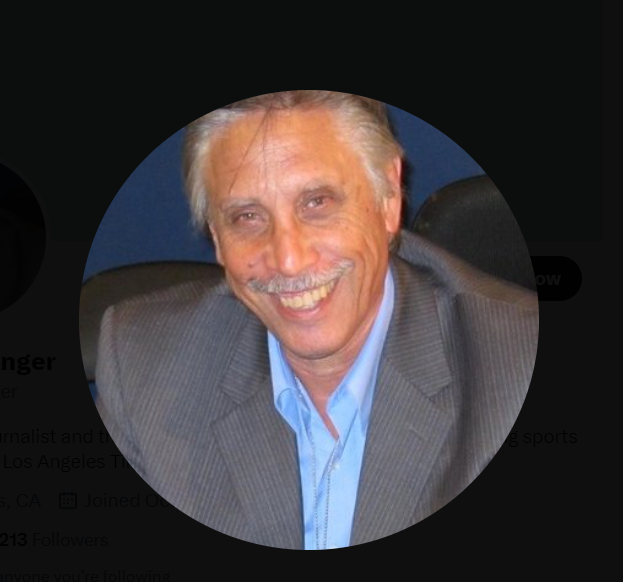

Former LA Times Scribe Steve Springer Reflects on His Days on the Boxing Beat

Nestled in Southern California’s San Fernando Valley, Steve Springer, a former sportswriter who for nearly 35 years covered several sports including the world of boxing, is at peace.

Springer, who spent 25 years at the Los Angeles Times, is definitely thankful for the opportunity to be ringside, which he was for 23 years, but doesn’t miss those days when he covered boxing.

“I really don’t keep up with it like I used to. I don’t find many of today’s fighters interesting or exciting and I don’t have any interest in MMA or WrestleMania,” he said. “Yes, I know, I’m just an old guy living in the past, but it was a glorious past.”

In what way is boxing different for Springer, who wrote 14 books including three bestsellers?

“It’s changed, but not for the better. A century ago, the top sports columnists basically covered only four sports: boxing, baseball, horse racing and college football. Boxing’s popularity had faded by the time I covered the sport (1985 to 2008), but was still relevant,” he offered. “Today, however, it ranks third in popularity among combat sports behind MMA and WrestleMania. Back when I covered boxing, Butterbean, an overweight four-round fighter, was a novelty act, comic relief before the big matches. Today, Jake Paul, another gimmick, wannabe boxer, is a main attraction. Sad, but true.”

Springer didn’t intend to become a sportswriter. Instead he hoped to be the second coming of Vin Scully, the legendary Dodgers announcer who for 67 years was the voice of the team.

Springer did play-by-play for basketball, football and baseball at California State University Northridge, where he graduated in 1968 with a broadcasting degree and later did play-by-play for high school football in El Centro from 1969 through 1972.

Springer kicked off his writing career in 1974 at the Thousand Oaks News Chronicle where he later became sports editor and won various awards, then left in 1979 when he joined the Orange County Register where he worked until 1983, covering the Lakers before being hired by the Times that same year.

Once assigned to boxing, what was the attraction for Springer?

“The opportunity to cover dramatic life-and-death events and write about colorful, fascinating people who have often had to battle all their lives just to survive,” he said of what made boxing exciting. “Every fighter has a story and no one in boxing ever refuses to tell it to you unless it’s because they have just been knocked out.”

Interviewing some of the legends was for Springer the whipped cream on the ice cream sundae.

“Given an opportunity to talk to Muhammad Ali, Don King, Mike Tyson, Bob Arum, Floyd Mayweather Jr., George Foreman and Joe Frazier, to name just a few, there’s no chance you’ll walk away without a dozen or more new stories floating around in your head,” he said.

And if you’re lucky, you might speak with someone not entirely famous but still worthy of your time.

“Actually, everybody in the sport has a tale worth telling, from the trainers and corner men to the promoters and managers,” Springer said. “There was a little-known member of King’s organization who once gave me a line that kind of summed up the richness of the material generated by those in the fight game. “I was in boxing for 40 years,” he said. “The first three years were about boxing. The last 37 were about revenge.”

Sometimes what happens inside the ring during the course of a career has debilitating results.

This wasn’t pleasant for Springer, who was inducted into the Southern California Jewish Hall of Fame and was the recipient of the Nat Fleischer Award given by the Boxing Writers Association of America.

“I didn’t like the results of the brutality in the ring. I covered two fights that ended with one of the boxers dying,” he pointed out. “I wrote a story about a fighter named Bobby Chacon who had to carry a map of his neighborhood in his shirt pocket because he couldn’t remember how to find his way home. He was 44 years old at the time. And, of course, there was the sadness of watching Ali in his final years. Very few boxing stories end happily.”

A featherweight and super featherweight champion, Chacon passed away in 2016 at the age of 64.

Springer covered the entirety of Oscar De La Hoya’s epic career and co-wrote a biography with the 1992 Olympic gold medalist titled “American Son: My Story.”

De La Hoya is a complex person and one Springer knows fairly well.

“Oscar has two passions outside of boxing: golf and singing. He often insisted that he was going to try to join the Senior PGA golf tour when he qualified by reaching the age of 50. He hit that milestone several months ago, but there are no signs yet that he’s seriously considering trying to take that big leap,” he said.

“Oscar has a great sense of humor on the golf course. Playing with him one time, I hit my tee shot into a ravine so far down that I couldn’t see the flag on the green. With Oscar waiting for me on that green, I hit a blind shot that somehow landed in the cup. From then on, Oscar always called me Mr. Hole-In-Two.”

Springer spoke about De La Hoya’s fondness for music.

“His love of music came from his mother, Cecilia, who died of cancer at 39. He still remembers the day he got into his mother’s car to join her in a loud duet in the driveway of their family home,” he said. “Oscar went on to sing a song that was nominated for a Grammy for Best Latin Pop Performance.”

Springer quoted De La Hoya. “If I boxed because of my father,” he said, “why not sing because of my mother?”

When Mike Tyson was the heavyweight kingpin, noted Springer, anything could happen inside or outside the ring.

“The obvious choice [for the most bizarre fight that I covered] had nothing to do with the skills of the fighters. It was because of the jarring end of the fight after Tyson bit off part of Evander Holyfield’s right ear and spit it out on the canvas in the third round, then bit Holyfield’s left ear before the round was over,” he said of that eventful evening at the MGM Grand Garden Arena in 1997.

Springer was also there at Tyson’s hearing on the matter.

“At a hearing later held by the Nevada State Athletic Commission to decide if Tyson should be stripped of his license, he was asked if he wished to say anything before a vote was taken,” Springer said. “All I have to say,” Tyson said, “is, I’m not Mother Teresa, but I’m not Charles Manson either.”

Springer added: “I was also present five years later at a New York press conference for a Tyson-Lennox Lewis match that turned into a brawl which ended with Tyson sinking his teeth into one of Lewis’ legs,” he recalled. “Tyson was definitely the Hannibal Lecter of the ring.”

Springer’s coverage and storylines included numerous all-time greats, whom he admired for different reasons.

“Manny Pacquiao for his ability to stretch his talent all the way from flyweight to junior middleweight, while winning the lineal championship in five weight divisions (flyweight, featherweight, super featherweight, light welterweight and welterweight) in a career that spanned four decades,” he said, “George Foreman and Bernard Hopkins for their longevity, each fighting for 28 years with Foreman becoming the oldest heavyweight champion at 45, then retiring at 48, Hopkins at 51, and Floyd Mayweather for going 50-0, beating the record of the legendary Rocky Marciano.”

Boxers have a vested interest in speaking with the press according to Springer.

“I’ve never had a boxer say, “No comment.” In other sports, athletes are exposed to the media for months at a time through a long season,” he said. “They get tired of talking to reporters, especially when they are in a slump. There is no pressure on them to talk because, if they duck reporters, they are still assured of their playing time as long as they produce.”

This isn’t true for boxers. “Fighters, on the other hand, have no guarantees about future bouts. If they are ambitious young fighters, they need to make a name for themselves. If they are serious contenders, they need a title-holder to agree to fight them. Even if they themselves hold a title, they need publicity to beef up interest in their next fight, thus beefing up the size of their purse,” he said. “The more time they can get their face on TV or their name in the papers or on the Internet, the more opportunities they will have for fame and fortune. ‘No comment’ doesn’t cut it.”

There were some negatives covering the manly sport according to Springer.

“I never felt conflicted. I certainly didn’t like seeing fighters sadly losing their lives or, even if they survived, losing their minds, suffering from pugilistic dementia, a condition often referred to as punch drunk,” he said. “It’s the risk they all knowingly take because, in so many cases, it’s the best path open to them to escape the poverty and despair that plagues so many of them and their families.”

What does Springer believe will make boxing more palatable for the viewer?

“The biggest problem facing boxing is the sanctioning bodies, the WBC, WBA, IBF, WBO and several smaller organizations,” he said. “This alphabet soup spells disaster for the sport. While the WBC is the biggest and most authentic of the group, even though it too has flaws, the others often have their own designated champions. Every titleholder is forced to pay exorbitant sanctioning fees in order to keep their championship belts.”

Springer does reference the good old days when he was on the boxing beat.

“Long gone and never to return are the days when there was only one recognized champ in each weight division and many qualified contenders,” he said. “Back then, every sports fan, a follower of boxing or not, knew the name of the one and only heavyweight champion.”

The offshoot is that there are additional hurdles for everyone involved.

“As a result of this mishmash system, the best fights often never happen because of disputes over money, rankings of the fighters and other issues,” Springer said. “If there was a national boxing commissioner and he or she had the power to establish national rankings and order fights between champions of various sanctioning bodies, boxing itself would be the winner. Imagine if the Dodgers refused to play the Giants or the Lakers wouldn’t schedule the Celtics for whatever reason. It wouldn’t take long for fans of MLB or the NBA to start looking elsewhere to spend their dollars.”

Springer concluded his thought: “I can’t foresee this radical change to ever happen in boxing,” he said. “Too much money and too much power would be lost by the powers that be. The biggest losers with the status quo are the boxing fans.”

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoThomas Hauser’s Literary Notes: Johnny Greaves Tells a Sad Tale

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoBoxing Notes and Nuggets from Thomas Hauser

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRolly Romero Upsets Ryan Garcia in the Finale of a Times Square Tripleheader

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

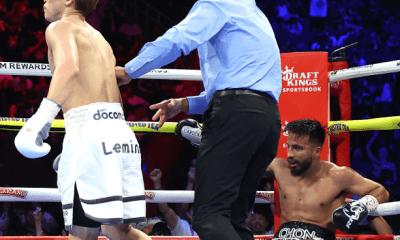

Featured Articles4 weeks agoUndercard Results and Recaps from the Inoue-Cardenas Show in Las Vegas

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoCanelo Alvarez Upends Dancing Machine William Scull in Saudi Arabia

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoBombs Away in Las Vegas where Inoue and Espinoza Scored Smashing Triumphs

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: The Good, the Bad, and the (Mostly) Ugly; a Weekend Boxing Recap and More

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

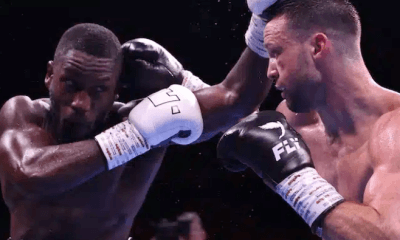

Featured Articles1 week agoEkow Essuman Upsets Josh Taylor and Moses Itauma Blasts Out Mike Balogun in Glasgow