Featured Articles

Before ‘Bud’ Crawford, there was Ace Hudkins: A Look Back at the ‘Nebraska Wildcat’

Before ‘Bud’ Crawford, there was Ace Hudkins: A Look Back at the ‘Nebraska Wildcat’

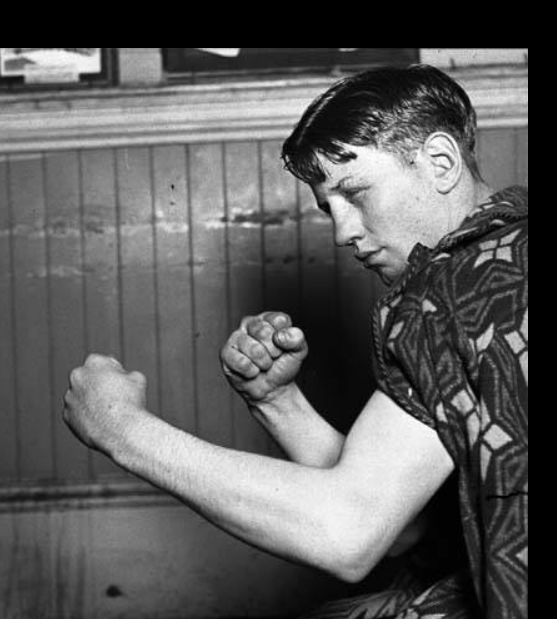

During his career, Ace Hudkins was recognized as the California state champion in two weight classes – lightweight and heavyweight. He fought before crowds of 30,000-plus at baseball parks in New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago and he came within a shade of wresting the world middleweight title from the great Mickey Walker, losing a decision widely assailed as a heist.

In light of Terence “Bud” Crawford’s brilliant performance last Saturday against Errol Spence, now would seem to be a good time to dust off the Ace Hudkins omnibus. Before Crawford, there was little argument that Hudkins was the best fighter ever born and raised in Nebraska.

Asa “Ace” Hudkins was born in 1905 in Valparaiso, a little farming town where his father owned a livery stable. His father died young and the family moved to Lincoln where Ace took up boxing at age 16 after first attracting notice as a wrestler with the Lincoln, Nebraska YMCA. He fought exclusively in and around the Cornhusker State before turning up in Los Angeles in December of 1924.

Los Angeles in 1924 was a boomtown. The population of LA County soared from 936,000 to 2.2 million during the decade of the 1920s. In December of 1924, boxing in the Golden State was on the cusp of a renaissance, the result of the new state law that took effect that month that overturned the law in effect since 1914 that had restricted matches to four rounds. A new arena for boxing was rising from the dirt on South Grand Avenue, the Olympic Auditorium, offering an alternative to Hollywood Legion Stadium, which itself was fairly new.

Having two venues for boxing in close proximity in a large and rapidly growing city was bound to drive up purses and Ace Hudkins was one of many leather-pushers who followed the scent of fresh money to Southern California in the mid-1920s.

In Hudkins’ second fight in California, on Jan. 9, 1925, he was thrust against California lightweight champion Tommy Carter. A capacity crowd was on hand for an event that was somewhat historic, marking the first “long fight” (i.e., 10-rounder) at Hollywood Legion Stadium.

The fight, by all accounts, was a doozy. Carter had the Nebraskan almost out on his feet in the third round, but Hudkins roared back and almost finished Carter in the sixth. The bout went the full distance and there was scarcely a dull moment. The referee awarded the match to Hudkins, a foregone conclusion as “the gawky, freckled kid from Nebraska,” as reporter Ed Frayne phrased it, “won conclusively.”

By then, Ace Hudkins had 45 pro fights under his belt although he was yet only 19 years old. Reporters took to referencing him as the Nebraska Wildcat and predicted that he would go far if he tightened up his defense.

Hudkins had 11 more fights before the year was out, all but one in Los Angeles. The exception was a 10-round contest in East Chicago, Indiana, against Sid Terris. The lightweight title was then in dispute – the great Benny Leonard had retired – and the winner would claim the title, notwithstanding the fact that the New York Commission recognized Buffalo’s Jimmy Goodrich.

The bout was a thriller climaxed by a breathtaking final round that had the crowd on its feet the whole while. Ace never took a backward step, but the consensus of ringside reporters was that he was out-boxed. This was no disgrace. Terris, a clever New Yorker with a magnificent record (66-4-2 heading in, per boxrec) would be inducted posthumously into the International Boxing Hall of Fame.

During the bout, Ace was warned several times by referee Dave Barry (he of “long count” fame) for low blows and general roughhousing and this became part of his persona. Retrospectives of Ace Hudkins invariably touch upon his penchant for flouting the Queensberry code. “Whatever it takes (to win),” was his mantra.

Coney Island

Ace had better success against Terris’s landsman Ruby Goldstein. A baby-faced knockout artist from New York’s Lower East Side who would go on to become a prominent referee, Goldstein, nicknamed the Jewel of the Ghetto, was 23-0 when he was pitted against Hudkins on June 25, 1926, in the outdoor arena at Coney Island.

New York then had a rule that mandated that a fighter had to be at least 21 years old to compete in a 10-rounder. Both Hudkins and Goldstein were under the limit and their match was slated for six frames. Despite this encumbrance, a crowd estimated as high as 18,000 swarmed into Coney Island Stadium to see the Jewish phenom perform against the mysterious “wildcat” from out west who was making his Big Apple debut.

Things started swimmingly for Goldstein. Midway through the first round, he put Hudkins on the deck with a straight right hand. “At this stage,” wrote the ringside reporter for the Brooklyn Standard Union, “the buttonhole makers who wagered their shekels on Ruby were counting the profits.” But Hudkins was up at the count of six and bobbed and weaved and clinched to last out the round.

Goldstein won the second round also, but Ace landed a big right hand just before the bell and from that point it was all Hudkins who ended the match in the fourth with a paralyzing left hook that put Goldstein down for the count. A physician clambered into the ring and stayed with him until he regained his senses and young Ruby would leave the ring in tears.

Hudkins had three more fights in New York before returning to Los Angeles where he racked up five straight wins, outpointing such notables as Mexican-American trailblazer Bert Colima and future Hall of Famer Lew Tendler.

Welterweight

When Ace returned to New York in the summer of 1927, he was a full-fledged welterweight. He carried 146 pounds for his June 15 date with Sergeant Sammy Baker at the Polo Grounds on a card studded with leading lightweight contenders.

The guest of honor was Col. Charles Lindbergh who had flown solo from New York to Paris the preceding month, a feat that made him a national hero. Lindbergh came there at the behest of Ace Hudkins. It turned out that they were old friends who met when Lindbergh, three years older than Ace, was in Lincoln attending flight school.

The motorcade that transported Lindbergh and his host Mayor Jimmy Walker to the fight ran into traffic and Lindbergh missed the first two rounds. When he finally took his seat, Hudkins’ right eye was already purplish and swollen. The cut over the eye burst wide open in round seven and the referee waived the fight off.

Hudkins got his revenge the following month in a fight for the ages at LA’s Wrigley Field, home to the city’s Triple-A baseball teams.

Hudkins-Baker II was a gory spectacle. At the finish, said a ringside scribe, “both fighters were covered with blood and many ringside spectators wished they had come equipped with umbrellas.” Harry Grayson, soon to be one of America’s highest-paid newspaper writers as the sports editor of the Newspaper Enterprise Association, could not contain his enthusiasm. “Veterans declared it to be the most savage contest their tired old eyes ever gazed upon,” said Grayson. “This writer never saw a more bitterly contested duel between great fighters.”

The fourth round ended with Sergeant Baker flat on his back, unconscious. But the bell sounded when the referee reached the count of nine and Baker recovered during the one-minute respite and fought his way back into the fight. The turnout, at least 30,000, was said to be the largest in LA boxing history and the gate receipts exceeded the previous high by a good margin.

A fighter of Sicilian extraction from Baltimore, Joe Dundee, then had the strongest claim to the welterweight title. Hudkins signed to meet him at Wrigley Field on Nov. 4. 1927. What ensued was one of the nastiest riots in California boxing history.

Dundee refused to come out of his dressing room when the promoter failed to make good on his guaranteed $60,000 fee. When that became obvious, fistfights erupted like wildfires in every section of the enclosure. Some of the belligerents managed to make their way into the ring. The battle royal collapsed the ropes on one side of the ring and a score of men landed on press row, crushing typewriters and telegraph equipment. Every available policeman in the city was dispatched to the ballpark where they “wielded their nightsticks with vigor” to quell the conflagration.

Middleweight

Hudkins then set his sights on middleweight champion Mickey Walker, the Toy Bulldog, a former welterweight title-holder who would go on to defeat some of the leading heavyweight contenders before his career had wended its course. While he was waiting, he engaged in several more fights, notably a rubber match with Sergeant Sammy Baker at Madison Square Garden. This bout wasn’t as gory as their second fight, but was every bit as robust. The decision went to the “wildcat” who struck the reporter from the New York Daily News as a throwback to the Stone Age.

Ace Hudkins and Mickey Walker collided on June 21, 1928, at Chicago’s Comiskey Park. It was 10-rounder, the limit then in effect in Chicago for any prizefight, whether for a world title or otherwise. The turnout, purportedly 30,000, was impressive considering the ominous skies, a portent of the torrential downpour that larruped the crowd in the final two rounds.

It was a bloody, tightly-contested affair and, at the conclusion, most of the reporters were in accord with the referee who deemed Ace Hudkins the winner. But both judges dissented (their scorecards were not made public) and Walker retained his crown.

Despite the drenching from the cloudburst, many in the crowd lingered long after the fight to vent their displeasure, holding up the walk-out fight. “It was one of the wildest demonstrations of disapproval any championship fight has witnessed in recent years, lasting fifteen minutes in full volume and a half-hour in more sporadic form,” said the correspondent for the Associated Press.

The damage was starting to take its toll on the Nebraska Wildcat, a glutton for punishment. He lured Mickey Walker to LA for a rematch, but their contest, on Oct. 6, 1929, was a pale imitation of their first encounter. The reporter for the Los Angeles Record scored the bout 6-1-3 for the Toy Bulldog while conceding that his tally may have been a bit generous to Hudkins. This may, however, have been Hudkins’ best payday. The turnout, 21,370, including many Hollywood stars, shattered the California record for gate receipts.

Light Heavyweight

Undeterred by his second failed bid at Walker’s middleweight title, Hudkins set his sights on the light heavyweight diadem. To this end, he challenged the leading contender and future title-holder Maxie Rosebloom.

Their match at Madison Square Garden on Feb. 14, 1930, although a predictably foul-filled tussle, was an entertaining affair. Ace won the first three rounds, but then faded. In reaching for a stab at the light heavyweight title, he had reached too far.

Hudkins, clearly past his prime although only 25 years old, would have only seven more fights before calling it quits. In the fifth of those seven fights, however, he turned back the clock, winning the California heavyweight title from Dynamite Jackson. Hudkins upended Jackson before a packed house at the Olympic Auditorium on Sept. 15, 1931, in a match pushed back three weeks after Ace suffered a bad case of poison ivy.

Heavyweight

In his customary slashing and mauling style, Hudkins wore down his 205-pound adversary and coasted home after building an insurmountable lead. “The spectacle of the 173-pounder moving his heavier foe around the ring, much as husky gentlemen shove pianos, gave the crowd many a chuckle,” said the reporter for the Los Angeles Evening Express.

Ace had previously defeated Chicago heavyweight hopeful King Levinsky and his triumph over Jackson sparked talk of a match between him and rising heavyweight star Max Baer. That would have been an interesting match-up, if only because it would have paired two native Nebraskans. Baer was born in Omaha but spent his formative years in Colorado and Northern California.

That match never materialized and Ace’s win over Dynamite Jackson proved to be his last hurrah. He surrendered the title to Lee Ramage in his first defense and his performance in his swan song fight with Utah journeyman Wesley Ketchell was desultory. The best that could be said is that he lasted the distance in both matches. The only man that ever stopped him was Sergeant Sammy Baker and Ace avenged that setback twice.

After the Fall

In retirement, Hudkins became an alcoholic which led to numerous brushes with the law resulting from bar brawls, drunk driving, and such, and a near-fatal incident in 1933 when he was shot in the chest by the proprietor of a nightclub. But he kicked the habit and became a successful businessman. With his three brothers – Clyde, Art, and Ode – he opened a ranch that rented horses and related equipment to Hollywood filmmakers and TV studios in an era when Westerns were the backbone of the industry. Roy Rogers’ famous “Trigger” and the original “Silver” of Lone Ranger fame were boarded and trained at the Hudkins Brothers North Hollywood facility. Ace appeared with some of his horses in a few movies where he was an uncredited stunt rider. He was battling Parkinson’s disease when he passed away at age 67 in 1973.

You won’t find a plaque for Ace Hudkins at the International Boxing Hall of Fame, but that may yet happen. In this reporter’s opinion, he is no less qualified than Tiger Jack Fox, the most recent inductee in the Old Timer category, and Hudkins created much more of a stir during his brief but tumultuous career.

As to whether Ace could hold his own with Bud Crawford, that’s a rhetorical question. Crawford is a special talent. There are many dimensions to his game, whereas Hudkins, although tough as nails, had only one gear. A reporter seeking the right adjective to describe his technique, came up with the word longshoreman. But despite his limitations, it would be hard to argue with former LA Times scribe Paul Lowry who called Hudkins the best near-champion of his era.

Paul Gallico referenced Ace Hudkins in his classic memoir, “Farewell to Sport.” We’ll give Gallico the last word, er, words: “[He] was tough, hard, mean, cantankerous, combative, foul, nasty, courageous, acrimonious, and filled at all times with bitter and flaming lust for battle.”

—

Editor’s Note: Kristine Sader, a distant relative who had access to Ace Hudkins’ scrapbooks, wrote a biography of the boxer that was published in 2018. “Ace Hudkins: Boxing with the Nebraska Wildcat,” a $25 paperback, can be found at Amazon.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 330: Matchroom in New York plus the Latest on Canelo-Crawford

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoVito Mielnicki Jr Whitewashes Kamil Gardzielik Before the Home Folks in Newark

-

Featured Articles8 hours ago

Featured Articles8 hours agoResults and Recaps from New York Where Taylor Edged Serrano Once Again

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoCatching Up with Clay Moyle Who Talks About His Massive Collection of Boxing Books

-

Featured Articles5 days ago

Featured Articles5 days agoFrom a Sympathetic Figure to a Pariah: The Travails of Julio Cesar Chavez Jr

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoMore Medals for Hawaii’s Patricio Family at the USA Boxing Summer Festival

-

Featured Articles7 days ago

Featured Articles7 days agoCatterall vs Eubank Ends Prematurely; Catterall Wins a Technical Decision

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRichardson Hitchins Batters and Stops George Kambosos at Madison Square Garden