Featured Articles

Oleksandr Usyk from a Historical Perspective

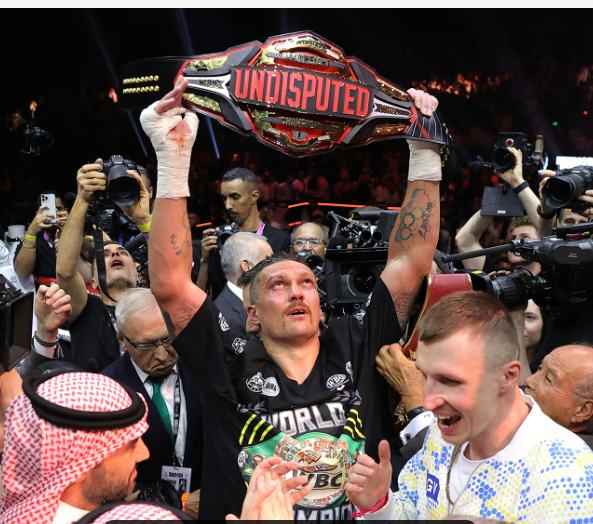

Oleksandr Usyk flipped the heavyweight division onto its head this past Saturday night in the Kingdom Arena, Riyadh, travelling a long way from home to seal his greatest victory. Usyk, small by modern heavyweight standards, towers over most men at 6’3″ and 220lbs and sporting a reach that lineal champions Ezzard Charles or Joe Walcott would have killed for. Things have changed though, and in the middle rounds of his war with Tyson Fury, Usyk suddenly appeared tiny. Fury, a giant at around 6’8” and over 260lbs seems a heavyweight for this century. Usyk, a journeyman in the most ancient sense of the word, feels like a throwback to a more savage time. His greatest achievements have taken place on foreign soil. The last time he boxed at home was almost a decade ago and given the situation in Ukraine and given Usyk’s 37 years, it is unlikely he will ever box there again.

Usyk took chances in the seventh and especially the eighth to take charge of a fight that seemed to be slipping away from him. In the vertigo inducing ninth, it was he, not Fury who appeared the giant. Usyk draped the Englishman over the ropes like so much fresh meat and tenderised him to within an inch of unconsciousness, the sheer hugeness of Fury perhaps preventing a referee’s intervention on behalf of his opponent, and not for the first time. Against both Deontay Wilder (the first fight) and Otto Wallin, a more squeamish official would have stepped in and stopped the fight, and here, too, there was a case. If Usyk seems a throwback, then Fury has been refereed like one, spared stoppages likely to be inflicted upon his peers, he was allowed once again to continue boxing, as Joe Louis was against Max Schmeling, or Jack Dempsey was against Luis Pirpo. But with Fury buckled at the knees, Usyk seemed the true heavy man in the ring.

In historical terms, Usyk is not a small heavyweight. He would have dwarfed “The Galveston Giant” Jack Johnson in the ring and loomed large over “Big” George Foreman. Usyk has every attribute necessary to make an unpleasant evening for Joe Louis, but it should be noted that while his footwork and speed and technical excellence would be the source of the discomfort, his excess of height and reach are the wildcards. Usyk would seem two to three weight classes bigger than Rocky Marciano, mainly because he is, and the towering Sonny Liston would look up. Circus strongman Jess Willard and the mob-sponsored Primo Carnera would both look down on Usyk – but not by that much. Usyk would stand eye to eye with Muhammad Ali but prime-for-prime he would outweigh him by ten pounds, as he would Larry Holmes. We must skip Mike Tyson and Evander Holyfield and reach all the way into the Lennox Lewis era before we find men from history that truly out-size Usyk on a consistent basis.

Size, as Usyk has proven, is far from everything. Big by historical standards, he is small by modern standards. What else is now true in the wake of the seismic fistic events of Saturday night? Firstly, Usyk is unquestionably ranked the #1 heavyweight in the world. Of this, there can be no dispute. Accounting for his two wonderful defeats of another “super” heavyweight, Anthony Joshua, he is 3-0 against the rest of the top five and sitting unassailably at the head of the heavyweight table. More, and I have been surprised to see it disputed in some corners, Usyk is now almost as equally unassailably the pound-for-pound number one. The only fighter breathing the same air as Usyk right now is Naoya Inoue. Inoue has been operating at or near the highest level for longer, but the level of his opposition has not been as rarefied. Comparing the first phase opposition defeated by Naoya to the murderer’s row of cruiserweights that Usyk ran into during the Super Six series can lead to only one conclusion. Although Naoya’s busy, weight-class-bursting style has topped him out for most of the past two to three years, only one of these men has consistently been beating bigger, taller, longer opposition at the highest level, and that is Usyk. It is not a matter of opinion – he is the smallest man in my heavyweight top ten.

01 – Oleksandr Usyk

02 – Anthony Joshua

03 – Joseph Parker

04 – Tyson Fury

05 – Filip Hrgovic

06 – Zhilei Zhang

07 – Agit Kabayel

08 – Daneil Dubois

09 – Martin Bakole

10 – Joe Joyce

Usyk lives among giants now and where there is parity of height (Kabayel) he is the lighter man by 15 pounds. This is not true of Naoya, who despite his weight-hopping, still manages to run into fighters of the same height and of shorter reach. The opposition argument is narrow, but the relative size opposition is not and there is no pound-for-pound credential more significant than that of consistently out-fighting bigger men. Usyk has done so and will continue to do so for as long as he fights. There is simply no smaller man in his class.

Not since the heyday of Mike Tyson and Evander Holyfield has a lineal heavyweight champion consistently fought bigger men and not since Mike’s hype-infused prime has a heavyweight menaced the number one pound-for-pound spot. Usyk has not enjoyed anything like the same machine support as Mike did; indeed, he has laboured in the shadow of more prominent men until such time as he thrashed them. He is a true manifestation of pound-for-pound glory in the unlimited class. Where does this leave him in terms of all-time standing?

I am reluctant to rate active fighters for reasons that are obvious enough; Usyk could be pole-axed in three by an irate Fury in a December rematch and all this ink is for naught. But what I am willing to do is play let’s pretend and imagine Usyk as retired and consider his place in heavyweight history now.

Usyk’s raw numbers are low-grade at just 22-0 with 14 knockouts. Worse, most of this was built in the cruiserweight division and not the heavyweight division. Against men weighing in as heavyweights, Uysk is essentially 7-0, and only 3-0 against ranked opposition. On the other hand, one of these victories came against Daniel Dubois, now ranked, and the 3-0 was posted against Tyson Fury, generally held to be the best or second-best heavyweight in the world, and Anthony Joshua, ranked behind only Fury at the time of his first fight with Usyk. So, when he stepped up, he stepped up to tackle the best in the world and has become lineal as a result. It’s a hard ledger to wrestle with, but fortunately we have a career that is comparable in the shape of Gene Tunney.

Tunney, a career light-heavyweight, earned a heavyweight legacy built of essentially one man: Jack Dempsey. Past-prime and inactive, Dempsey was ripped apart by Tunney in their legendary first fight and did better in a losing effort against the genius “Fighting Marine” in a rematch, much like Joshua did against Usyk. Tunney then boxed the limited but game Tom Heeney and retired. The rest of his heavyweight career was spent beating great middleweights like Harry Greb and limited losing-streak gatekeepers like Charley Weinert and Martin Burke. One thing that must be noted is that Tunney is matching men who are smaller than Usyk’s cruiserweight opposition to his heavyweight credit. Men like Mairis Briedis and Murat Gassiev would have been big men in Tunney’s era, but they aren’t counted towards heavyweight legacy for the Ukrainian – either would constitute Tunney’s second-best heavyweight scalp, I think. Tunney’s wider resume does not necessarily include fighters who compare that favourably even to Dereck Chisora or Chaz Witherspoon, the men who make up Usyk’s second layer of opposition.

The point is, Tunney was made a legend for defeating a champion. Both Fury and Joshua were active, physically enormous fighters that Usyk simply unmanned with a type of genius Gene Tunney would have stood to applaud. Tunney appended to his light-heavyweight career the important part of a heavyweight career – the part where you fight and beat the champion, and it has made him a stalwart of heavyweight history. This, Usyk too has achieved, but I have been more impressed with Usyk’s summit than Tunney’s. To be direct: Usyk should rate higher at heavyweight than Tunney.

What that means is that the top twenty at heavyweight is the minimum Usyk can expect from history’s eye should he retire undefeated. In such a case, I would place Usyk in this sort of company:

18 – Ezzard Charles

19 – Oleksandr Usyk

20 – Jersey Joe Walcott

21 – James J Corbett

22 – Peter Jackson

23 – Ken Norton

24 – Max Schmeling

25 – Vitali Klitschko

26 – Riddick Bowe

27 – Gene Tunney

Also illustrative of a point is Tunney’s career pre-heavyweight. Tunney, every bit as brilliant as Usyk in the ring (although notably smaller, and successful against notably smaller opposition), laced up his gloves on close to ninety occasions and his level of competition dwarfs that of Usyk. That is no indictment. All it really means is that Usyk isn’t among the thirty greatest fighters ever to have drawn breath, like Tunney is. He can join an enormous and star-studded cast that includes Mike Tyson, Bernard Hopkins and Carlos Monzon in that. I do think, though, that Oleksandr Usyk’s career, were it to end tomorrow, could be readily compared to that of Evander Holyfield and that means that an unbeaten Usyk, lineal cruiserweight and heavyweight champion of the world, current pound-for-pound king, is within spitting distance of a list that captures the fifty greatest fighters in history.

56 – Ruben Olivares

57 – Wilfredo Gomez

58 – Vicente Saldivar

59 – Oleksandr Usyk

60 – Evander Holyfield

61 – Ted Kid Lewis

62 – Lou Ambers

63 – Rocky Marciano

64 – Abe Attell

65 – Manuel Ortiz

A retired Naoya Inoue would join him in the top seventy, I think, and a retired Bud Crawford the top ninety.

Boxing is dead, haven’t you heard?

Photo credit: Mikey Williams / Top Rank

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 330: Matchroom in New York plus the Latest on Canelo-Crawford

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoVito Mielnicki Jr Whitewashes Kamil Gardzielik Before the Home Folks in Newark

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

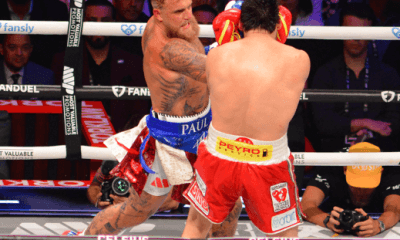

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap 329: Pacquiao is Back, Fabio in England and More

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoOpetaia and Nakatani Crush Overmatched Foes, Capping Off a Wild Boxing Weekend

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoCatching Up with Clay Moyle Who Talks About His Massive Collection of Boxing Books

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoFabio Wardley Comes from Behind to KO Justis Huni

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoMore Medals for Hawaii’s Patricio Family at the USA Boxing Summer Festival

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoDelving into ‘Hoopla’ with Notes on Books by George Plimpton and Joyce Carol Oates