Featured Articles

The 12 Greatest Middleweights of All Time

For the middleweights, world-conquering monsters arrived early. Of the three divisions I’ve studied so far, middleweight is by far the most dangerous territory. The top 12 that this division has whittled down through 130 years of competition is a thing of real beauty.

All styles and types are represented from furnace-bought killing pressure to the slick stylings of the defensive genius. Between them, these 12 men scored over 1,200 wins and more than 700 knockouts. Between them, they were stopped on just 16 occasions, incredible given some of the blind alleys even these giants groped their way into at the dark end of their careers.

My 12 will not be met with universal agreement. Accord is impossible. What I can tell you is that the Fifty has been thoroughly researched and the 12 that sits within it has been agonized over. In the end, I am happy with my top nine and for all that I consider 10, 11 and 12 to be interchangeable, which is something I had hoped to avoid, that top twelve is also, I hope, solid.

So listen.

#12 – JAKE LAMOTTA (83-19-4)

Jake LaMotta, the Bronx Bull, is the first man we encounter who has, at some point, ranked among the top ten in an earlier draft on this list. We have been knee deep in true greatness for some time now, but LaMotta represents a new height; he is a gatekeeper, at the very least, for the very greatest of the great middleweights.

“Jake never stopped coming, never stopped throwing punches and never stopped talking,” offered Sugar Ray Robinson, who defeated him 5-1 in perhaps the most celebrated middleweight series in boxing history. “You hit the guy with everything and he would just act like you were crazy.”

It’s as succinct and complete a description of LaMotta as a man and a fighter as you are likely to read. The Italian-American was a monster of durability, stopped just once in a long middleweight career by Robinson, who was in absolute top gear in forcing the referee’s intervention in the thirteenth round of their masterpiece from 1951, their LaMotta surged inexorably forwards, the ultimate middleweight tank, not devoid of skill (his jab is his best punch), but his real strength lay in the hellish pressure he brought to bear upon a generation of middleweights, most of whom folded to him in one way or another. Key among them are Robinson, Holman Williams, Robert Villemain, Marcel Cerdan and Laurent Dauthuille.

What kept him that bare smidge from the top ten are the asterisks that are scattered among those key results. Holman Williams was still dangerous when LaMotta edged him in 1946 but was unquestionably slipping and although probably sound, the decision was booed by some sections of the crowd. His determination to meet Williams and the other inhabitants of the Murderers’ Row marked him out as special but rarely went according to plan; he was soundly beaten by Lloyd Marshall and probably very fortunate to take a decision versus a green Bert Lytell.

Robert Villemain, a superb contender but certainly not a fighter under consideration for this list, split a pair with LaMotta and Jake’s winning effort seems to have been anything but with ringsiders almost unanimous in seeing Villemain as having been robbed. Villemain’s fellow Frenchman Laurent Dauthuile also went 1-1 with LaMotta, meeting first him over ten in 1949 in a thrilling fight that saw both cut and Dauthuile triumph on the cards. He came within seconds of taking the title in their 1950 rematch, ahead on points when LaMotta staged the most incredible rally in the history of the division to score a fifteenth round knockout and protect his championship.

Cerdan was the man LaMotta took the title from and he is fully credited for that thrilling victory – but it should be noted that Cerdan was injured in the course of the fight and certainly entitled to the rematch that fate interceded to prevent.

Nevertheless, LaMotta butchered numerous contenders in an action style. Had he a punch to match his chin, he would likely inhabit a spot in the top five.

#11 – FREDDIE STEELE (123-5-11)

Freddie Steele, possibly the most underrated middleweight ever to draw breath, moved up to the division in 1934 and spent the next three years and slightly less than fifty contests undefeated. Consider in the light of that fact the media cacophony that has accompanied Floyd Mayweather’s similar undefeated streak.

Not as storied as Mayweather in term of titles (he held a strap but never the lineal crown), nor is it likely that Steele defeated competition as excellent as Mayweather but he certainly did severe damage to the middleweight division from his Washington stronghold. Of his early middleweight displays (Steele had already done damage down at welterweight in his youth), his destruction of the creaking Vince Dundee is probably the most impressive. Feinting Dundee out of position, he was brutal in his aggressive rushing of the older fighter and very nearly destroyed him in the first with a flashing left hook that left Dundee sagging on the ropes; he barely beat the count and perhaps should not have bothered as Steele proceeded to batter him around the ring for three rounds until he was quite rightly rescued from his own diamond-cut determination.

Steele was a little over-exuberant once he had Dundee hurt and this caused him to miss often, rather compromising his excellent power, wonderful boxing and superb footwork (watch him repeatedly spin a bewildered Dundee off the ropes) but by 1936 he was in possession of a belt and had evolved into a much more deadly beast. Matching top fifty all-time light-heavyweight Gus Lesnevich he again he dropped his man with a pulverizing left-hook in the first, but this time he did not forget his boxing as he closed and Lesnevich was brutalized, horrifically, pulled before the end of the second.

Fred Apostoli, Solly Kreiger, Ken Overline and Babe Risko were among the other top men to fall to him and while readily available film is limited, he looks, to me, as good in the ring as just about any middleweight that ever boxed.

So why no higher? After all, when he finally began to lose it was only after having his breastbone broken, past-prime, against top-drawer opposition. Well, to my eye, Steele, also not unlike Mayweather, was often a little lucky in the timing of his fights with some of the big names he dispatched. Apostoli was a raw-green 6-0 when Steele defeated him; Solly Krieger was highly ranked at the time of their meeting but had just been beaten by the three-fight losing streak Glen Lee; Babe Risko was 3-3 in his last six; even Lesnevich was a number of years from his best wins. Ken Overlin may be his best victory, but even his form was a little patchy going in.

Steele has an argument for the top ten but it doesn’t quite find purchase here. He heralds monsters.

#10 – HOLMAN WILLIAMS (145-30-11)

Holman Williams washed up in Akron, Ohio, working as a janitor in the Wonder Club, a private establishment which in his final weeks was in the news due to a shooting on the premises. Whether connected or unconnected to the shooting, in the summer of 1967 someone crept into the Wonder Club and set it ablaze. Williams, who slept upstairs, woke to an inferno and “was overcome trying to escape.” He was fifty-two years old.

In his prime, he would have escaped that fire. He escaped, from as early as 1939, when he moved up from welterweight, an astonishing range of middleweight talent, duelling the leading lights of the black Murderer’s Row and others in a grotesquely under-celebrated run that lasted from 1939 until 1946 when the inevitable drop-off occurred. It was only in this late year that Jake LaMotta, certainly not reticent in his determination to meet the best, and the shyer Marcel Cerdan both crossed the street to meet the era’s best defensive specialist; even still, against a veteran of 170 fights, LaMotta struggled and his decision victory was booed by sections of the crowd. If LaMotta was in a nip-and-tuck affair that could have gone either way, Cerdan was outright lucky to bag a win as the bedraggled but still dangerous Williams injured his right in the fourth, boxing one-handed, and his leg in the eighth, unable to utilise his economic and confounding mobility for the ninth and tenth; still, the Associated Press card had the fight a draw.

It seems likely that had he matched these two legends even one year earlier, he would have emerged with two prized victories.

As it is we must judge him upon what he did in his frightening prime. This includes two victories over Lloyd Marshall, victories over Aaron Wade, Steve Belloise and Eddie Booker (who did manage to beat Williams but only at a poundage that rates it a light-heavyweight win), an astonishing four victories over Jack Chase and an epic series against Charley Burley which ended 3-3 with one no contest.

A middling puncher in his youth, Williams, who reportedly had a very relaxed attitude to training, had desperately fragile hands, a heinous disadvantage for a black 1940s middleweight who needed to box fifteen times and more in a year in order to make the ends meet. Williams adapted his style in order that he might survive the maelstrom of brilliance that surrounded him and the regularity with which he entered it, pulling his punches and playing for points. He became a poisonous shadow, hard to hit, lethal in his counters.

A brilliant boxer, he was capable, when necessary, of closing the distance and making war; that said, nothing he did successfully neutralised Cocoa Kid, a fellow Murderer’s Row contender who he met thirteen times and with whom he always struggled. That struggle was played out, for the most part, at welterweight; up at middle it was a closer affair and although the Kid still won their series at the weight, his margin of victory was narrower and it doesn’t form the limiting factor at 160lbs that it will at 147lbs.

Kid Tunero, Bert Lytell, Antonio Fernandez and Joe Carter were the other men to achieve rankings that were out-thought or out-fought by Williams. Some inconsistency dogged him and arguably a slot below Steele and LaMotta is a more reasonable one; that he three times bested Charley Burley was enough for me to nose him over the line and into the ten.

Other Top Fifty Middleweights Beaten: Cocoa Kid (#49), Jack Chase (#47), Lloyd Marshall (#31), Berty Lytell (#27), Charley Burley (Top Ten).

#09 – TOMMY RYAN (84-2-11; Newspaper Decisions 5-1-1)

Count them: three losses in more than a hundred fights. It is a true rarity to see so few losses in any centurion but Tommy Ryan was likely as brilliant and dominant a fighter as has ever lived.

The first of those losses came against the great Kid McCoy in 1896. Ryan was in his prime, but he was in his welterweight prime, and he weighed just 148lbs. Although he was crushed by McCoy it needs to be remembered that the Kid would go on to become a significant force at both light-heavyweight and heavyweight and that he carried a significant size advantage into their fight.

The second was suffered via a disqualification against George Green, the foul blow reported alternatively as “a light blow struck on Green’s shoulder” when he was down and a knee delivered to the face as Green crumpled before Ryan’s assault. Finally, he was beaten by heavyweight Denver Ed Martin in his final fight. He dropped a six round newspaper-decision to the big man having come out of retirement after a four year hiatus. He was forty-one years old.

Other than that, it’s just glory and greatness and the only factor that determines how highly he rates in the divisions he graced is identifying when he should be credited as a welterweight and when he should be credited as a middleweight.

For me, Ryan’s middleweight prime stretches from 1897 through to 1904 and his draw with Philadelphia Jack O’Brien; most primes are barracked by losses but Ryan was all but invincible at middleweight, and seemed literally so during his middleweight prime.

Perhaps his era’s definitive technical genius, he is said to have schooled both Jim Jeffries and, more surprisingly, the supposed “Grandfather of Boxing” James J Corbett on the finer points of boxing technique, but he was also one of the toughest middleweights in history. An orphan, the story goes that he wound up in Michigan scrapping his fellow newsboys for territory in semi-professional contests that morphed into a boxing career. Skin gloves and cobbles wrought a fighter carved of stone as he proved in defeating Tommy West in perhaps the bloodiest fight in boxing history. As well as innate toughness, he proved himself a wilting puncher scoring knockouts, some of them early, in the majority of his title defenses. A shot Jack Dempsey, the legendarily filthy “Mysterious” Billy Smith, West and Kid Carter were among the best to fall to him during the eight years during which he was almost universally recognized as the middleweight champion.

His was not an era of great strength but his consistent and extended dominance over it brings him in here just ahead of the mercurial Williams.

Other Top Fifty Middleweights Beaten: Jack Dempsey (#15)

#08 – CHARLEY BURLEY (83-12-2)

For boxing fans of a certain kind, the high regard in which the great Archie Moore holds the legendary Charley Burley is well known. Moore, who Burley thrashed, called Burley “inhuman” and “a human riveting gun,” striving, even with his dazzling lexicon, to make himself understood on the subject of the man he named “the best fighter I ever met” and a fighter who would have “beaten Ray Robinson”.

Less well known is the admiration of Burley by Moore’s on and off trainer, a man named Hiawatha Gray. Gray reportedly saw not only the greats of the 1940s and intimately knew both Moore and his incredible list of top drawer opposition, but also the greats of boxing’s infancy, men like Sam Langford, Jack Johnson, Joe Gans and Stanley Ketchel. Gray, like Moore, named Burley the best fighter he had ever seen according to Burley biographer Allen Rosenfeld. Ray Arcel, too, ranked Burley among the very greatest he saw. Eddie Futch named him one of the very best and introduced him to Larry Holmes as “the greatest fighter Pittsburgh has ever produced” without apologies to either Harry Greb or Billy Conn. Angelo Dundee was firm about refusing to name the greatest fighter of all time, claiming that opinions were “all about the time you come from” but when pressed, he named a handful of contenders that included Charley Burley.

For boxing geeks the opinion in which both peers and greats held Burley has become something of a cliché, but make no bones about it: those that saw him were enchanted beyond the norm.

I, too, am enchanted by Burley. The grainy highlights of him outclassing a light-heavyweight named Billy Smith is perhaps my favorite fight film. Smith, who was as prestigious a right-hand puncher as ever fought at light-heavyweight, comes charging across the ring and tries to nail Burley straight up with the same punch he used to obliterate Harold Johnson; he would have been as well trying to pick off a humming bird with a canon. Burley sidesteps neatly and then begins ten solid rounds of literally toying with the best puncher of the weight division fifteen pounds above his own, spinning him, feinting him into knots, countering him into a shambles. Most of all he muscles him in the clinches, matching the larger, more powerful man with ease.

Part cobra, part mongoose, Burley’s style was one of enormous complexity. He was a puncher, a defensive specialist, enormously strong physically and was equipped with a long reach and every punch in the book. Archie Moore describes a war machine and heavyweight slugger Elmer Ray, who ran afoul of the diminutive Burley in sparring, claimed that no man he ever faced from Ezzard Charles and Jersey Joe Walcott to the murderous Turkey Thompson hit as hard as he. But he will not be remembered as a puncher or a pirouetting dervish; he will be remembered first and foremost as a defensive genius and slickster.

He was all of those things. He was more.

Other Top Fifty Middleweights Beaten: Cocoa Kid (#49), Jack Chase (#47), Berty Lytell (#27), Holman Williams (Top Ten).

#07 – BERNARD HOPKINS (55-7-2)

The Executioner has very little company for contenders matched and dispatched. Lineal champion for only six defenses between his 2001 deconstruction of Felix Trinidad through to his questionable, though not unreasonable, decision loss on points to a motivated and primed Jermain Taylor in 2005, Hopkins was clearly the best middleweight in the world from as early as 1996, resulting in a near decade at the top of a division, a total of nine years. A moment’s pause for each of those years might reveal to the considered soul the level of commitment and the strength of character necessary to remaining the best fighter at a given weight for that length of time, regardless of the level of the competition.

He has named himself “biologically different than anyone else who walks the planet earth” but it is more likely that the difference is mental. Hopkins has eschewed chocolate for decades; the use of alcohol as a relaxant or stimulant is an alien concept. He visits the gym on Christmas day.

He is “different” alright.

But yes, that level of competition. Hopkins bested numerous contenders but he never beat a fighter in contention for this list. Trinidad is the closest he came to taking such a scalp and Trinidad was found to be something of a mirage at 160lbs, for all that he went into his fight with Hopkins as a favorite.

So Hopkins appears here as the ultimate realization of middleweight discipline. His style, too, was underpinned with determination, in fact I have never seen a fighter who boxed without slugging or swarming so married to domination as a concept. Initially aggressive and pressing (though always intelligent), Hopkins evolved into a fighter who dominated by surgery. He always knew the angle. If his opponent had a great jab he circled a half step outside the range and knew when to offer that step up to draw the punch. People say Hopkins “takes away his opponent’s best punch” but that’s not true, or it’s only half true. He turns his opponent’s best punch into a weakness.

This was very much the case against Trinidad. He kept his right hand high, his chin down, moved exclusively in quarter-steps or rushes and remained busy at that range which made a serious advantage of his reach, which forced Trinidad to consider straight punches first and foremost. In the end, Hopkins so entirely neutralized the lethal Tito hook that he was able to block and counter it for the knockout. That he had the presence of mind and physical cohesion to perform both actions with his right hand after twelve rounds is a testimony to both his technical ability and the gym-rat work-ethic that kept his mind free from cobwebs in the final round of a busy fight.

He was a cerebral alpha dog, the thinking man’s prison tough.

Hopkins probably fought defenses against more top five contenders than any other middleweight champion and nobody, until his razor-thin combats with Jermain Taylor, really troubled him. He was as dominant a champion as appears on this list. One can say what one likes about his competition, but in the departments of dominance, consistency and longevity, Hopkins is off the scale. The #7 spot is his due.

Other Top Fifty Middleweights Beaten: None

#06 – MIKE GIBBONS (65-3-4; Newspaper Decisions 48-8-4)

Mike Gibbons is a total anomaly, a white fighter who was clearly the best in the world in his weight division for a concerted spell who never became the champion. He laid claim to the title, like so many others in the wake of Stanley Ketchel’s death, but his claim was never recognized as full.

Mike was able to tempt three of the men who held the lineal title during his career into the ring at one stage or another. George Chip was the legitimate world champion in 1913 and 1914; Mike met and outclassed him on three separate occasions between 1917 and 1919. Al McCoy was the man who took the title from Chip. Three months before he did so, McCoy faced Mike. According to The Pittsburgh Press, McCoy landed “three or four punches” in ten uneventful but one-sided rounds which were hissed and booed by those in attendance. This may have been a part of Mike’s problem: he was a defensive specialist, the “St. Paul Phantom,” a fighter almost impossible to hit and given to taking protracted breaks even against world-class opposition, especially in no contests where no official decision was being rendered.

McCoy reigned for three years and despite his clear superiority over the new champion, Mike was never rewarded with a title fight. “I will meet McCoy any time,” was the line he parroted throughout that reign but it would be Mike O’Dowd who ended the McCoy title-run. Against O’Dowd, Mike enjoyed less dominance, dropping a twelve round decision in the twilight of the career and swapping newspapers decisions with the brutal champion prior to that. Against fellow uncrowned champion Harry Greb he managed a laudable 1-1, although it should be noted that Greb, while far from green, improved considerably after the first meeting between the two, a six-rounder fought in February of 1917.

Two newspaper decisions rendered over Jack Dillon and three over Jeff Smith in what appear to have been fascinating if sometimes slow encounters nail him down as great but his resume has enormous depth to go with these quality wins. Willie Brennan, Gus Christie, Bob Moha, Jimmy Clabby, Eddie McGoorty and Leo Houck, among others, fell to his stylings at some time or other.

A veteran of more than 130 fights, he was never stopped, a granite jaw barracking that legendary defense. Had he been champion he would have cracked the top five.

Other Top Fifty Middleweights Beaten: Jeff Smith (#41), Mike O’Dowd (#25), Jack Dillon (#19), Harry Greb (Top Ten).

#05 – STANLEY KETCHEL (53-5-5)

The definitive monster draws a veil across the top five.

By astonishing coincidence Stanley Ketchel shared an era with perhaps the only middleweight that could have rivaled him for the position of Chief Monster, Billy Papke. They fought wars, savage even for their savage era.

Papke exalted in suffering to an even greater extent than Ketchel, and was delivered to exaltation by his nemesis in June of 1908. Ketchel boxed Papke carefully, “he was not in a hurry” but rather “the coolest man in the house.” He used footwork and a shifting, “sideways” style that reads as almost spiderlike, to keep the brutal Papke off balance and under control; the result was a beating one-sided and impressive, so impressive it led the great Abe Attell to name Ketchel “the greatest fighter that ever lived.”

The rematch, too, provoked admiration. Jim Jeffries, the legendary heavyweight champion, labelled him “the gamest fighter I have ever seen” as Ketchel absorbed perhaps the most hellish beating of an era accustomed to such; so devastating was the punishment that Papke inflicted that by the eighth the crowd, accustomed to the brutalities of boxing in this era, called for the fight to be stopped. Jeffries, a fighter who made his bones soaking up violence, allowed the blood bath to continue into the twelfth. Ketchel’s face “was battered out of shape, as if Papke had knocked him about with a baseball bat as opposed to two fists”. Distracted by talk of a match with world heavyweight champion Tommy Burns, comforted by his one-sided drubbing of Papke on points, Ketchel, perhaps, had not applied himself in the usual way. “His face crooked, his mouth a mere gash,” he vanished into the desert, even his manager apparently unaware of his whereabouts.

When he re-emerged it was with a silent confidence that impressed even the newspapermen who had deemed him damaged goods. At the bell for their rubber, he told Papke, in a steady voice, that he would knock him out one round earlier than Papke had inflicted that ignominy upon him and then proceeded to do so. When he defeated Papke for a third time over twenty rounds some months later he was made Papke’s master for all time.

Ketchel had been an underdog to the much bigger Joe Thomas when he stumbled out of the brush all those years earlier but he crushed Thomas. Hugo Kelly had boxed fifty rounds with Jack Sullivan, thirty rounds with Burns and twenty rounds with Papke without incident; Ketchel dusted him in three. Sullivan, a defensive specialist more accustomed to boxing heavyweights than middleweights, dropped down in poundage to face Ketchel and was destroyed. In fact, while he was beaten by a light-heavyweight Sam Langford and a heavyweight Jack Johnson – no shame in either case – Ketchel was beaten just once at middleweight, by Papke, a defeat he three times avenged.

A lethal pressure fighter with off-scale power, an iron jaw, huge work-rate and limitless stamina, Ketchel dominated a superb era of middleweights during a career that saw him reign twice as the champion of the world.

Other Top Fifty Middleweights Beaten: Hugo Kelly (#50), Billy Papke (#23).

#04 – SUGAR RAY ROBINSON (173-19-6)

Sugar Ray Robinson should always herald something special when it comes to boxing history, and such is the case here; Robinson is the first man on this list to have been considered at some point for the #1 slot.

What caused him to tumble to #4 is his inconsistency at the weight. His incredible longevity in winning the middleweight title an astonishing five times is an achievement that makes it almost impossible to leave him out of the top six, but it must be quantified. Randy Turpin, Gene Fullmer and Carmen Basilio, all champions from whom he ripped the title, were only champions because he lost to them – in other words, it was his ability to win and lose with these men that enhances his standing whereas the likelihood is that Marvin Hagler and Carlos Monzon would have dominated all three twice. Additionally, if list-making is an art that is perfected with practice, I have learned to become wary of fighters who let many other fighters into the argument. Robinson was a champion when he lost to Turpin, Fullmer and Basilio and for all that only Turpin got to him in anything like his prime, those defeats chip away at the gold of his glory. If Robinson were ranked #1, say, then the chips of gold bagged by these wonderful middleweights become even more valuable and this leads to an artificial inflation of their standing. Here, then, is the signal I have heeded in ranking Robinson the least of the faces of middleweight’s Mount Rushmore.

Not that a higher berth would flatter him. Ray Robinson’s famous destruction of Jake LaMotta on Valentine’s Day 1951 is the single greatest performance by any fighter on film in my opinion.

That’s probably worth reiterating: I have never seen boxing done better than Robinson at his middleweight best, not by any fighter in any division. His great weakness at middle, his lack of physicality, he made a strength, crouching and landing booming right hands to the body around the corner of LaMotta’s fearsome tunnel vision, making space and digging with those famous short blows, a tactic he perfected against the granite-chinned Fullmer for the knock-out of the century in their 1957 rematch.

His domination of another champion, Bobo Olson, is also impressive, almost as impressive as his defeat in 1961 of Denny Moyer, not in and of itself a great achievement but a win by which he came to own victories over middleweight contenders from three different decades, something neither Monzon nor Hagler could achieve.

These observations are drier than those I might have made on the incredible gift the man had for moving and punching, of the most fluid yet devastating combinations ever to be performed in a boxing ring, but they are the pertinent ones when it comes to understanding his place in middleweight history.

Other Top Fifty Middleweights Beaten: Bobo Olson (45), Georgie Abrams (39) Randy Turpin (37), Gene Fullmer (24), Jake LaMotta (12).

#03 – MARVIN HAGLER (62-3-2)

Marvelous Marvin Hagler may be the most mis-understood great fighter in history.

Most famous of all his fights was the amazing 1985 showdown with Tommy Hearns in which he swarmed forwards and inside the deadly Hearns jab for an aggressive and brutal face-first assault, the result a third round knockout. Notorious, too, is his final fight, his controversial 1987 loss to Ray Leonard a fight in which, again, he adopted the role of aggressor as Leonard slipped and jived his way to a decision win. But that is not Hagler’s natural style. A stalker, yes, he was that, but more a pressure-stalker than an aggressive, pushy one as he appeared in those two contests. To put it simply, Hagler was a much better boxer than he was a brawler, and he was one of the better brawler’s in the division’s history.

That said, his careful methodology probably cost him the decision against Leonard and let the genius Duran come perilously close to taking a decision from him in 1982; but for the most part, Hagler’s legacy is perhaps the definitive alter to the savagery of the deliberate. The best examples of his true style are likely his two dominations of the direct Mustafa Hamsho. Hamsho, who convinced both media and public that he, of all the ranked contenders, was the best equipped to test Hagler, was in fact the perfect foil for this pragmatic puncher’s style, and in the first fight Hagler slipped, blocked and rode Hamsho’s attack all the while counter-punching him to pieces, remaining always just beyond his opponent’s most tender attentions. The ending was brutal.

But it was less brutal than the rematch, conjured by Hamsho in the wake of some moderate difficulties Hagler had had against the not dissimilar Juan Domingo Roldan. These difficulties were not recreated by Hamsho who once again was dismantled, this time in just three. This fight, in conjunction with the Hearns war, demonstrates the absurd difficulty born in matching Hagler. He had an iron jaw, a world class defense, really good punching power (of his twelve successful title defenses he won eleven by stoppage), was a good mover and a wonderful counter-puncher; but when Hamsho and Hearns plant their feet they get destroyed, are out-thundered by a fighter armed to the teeth and in possession of the accuracy to find all but the most elusive targets with sickening regularity. The surgical precision of the massive variety of right hands he used to butcher Hamsho in the third also special; the uppercuts he used in part to soften him some of the best you will see. This is not a head-to-head list as I have been at pains to stress, but I will say this: any fight in which Hagler be allowed to find those uppercuts is a fight he would win.

They played a part in victories over ranked men such as Mike Colbert, Bennie Briscoe, Alan Minter (the ruthlessly deposed champion), Fulgencio Obelmejias, Vito Antuofermo, Don Lee, Tony Sibson, John Mugabi and others; he was a king who brooked no authority.

Having said that, Hagler had as difficult apprenticeship as any fighter in the Top Ten and although there is no room to explore it here I think it is fair to say that it bore a fighter with a chip on his shoulder and one, too, in need of tactical direction – he could be confused, perhaps, by a vacuum. So few are his weakness though that we are reduced to groping for such quasi-psychological chinks in some of boxing history’s greatest armaments. A colossus of a fighter, Hagler would have made a worthy number one.

Other Top Fifty Middleweights Beaten: None

#02 – CARLOS MONZON (87-3-9)

Inscrutable, impermeable and perhaps unstoppable, Carlos Monzon went an astounding, record-breaking 15-0 in world title fights and went unbeaten despite excellent competition for an astounding twelve years. He was a horror to face and may have been the single best middleweight ever to pull on the gloves.

Why? That’s the question that tortured me; what made him the best, if that is what he was?

I have given up recounting the training regimes and commitment of the great ones – they are all similar in that they call for either Spartan commitment to training, or enormous activity that precluded the need for such training; Monzon trained hard, but he also smoked heavily, reportedly sucking down up to 100 a day, although I can hardly believe this. Smoking, supposedly, even while completing training runs, here was a fighter that was more impressive in the late rounds of championship fights than almost any other. Sparring with an increasing number of statuesque models and South American movie stars as his fame increased, Monzon seems to have actually been what rumor-mongers tried to make Harry Greb: a playboy who trained on pleasure while simultaneously becoming perhaps the greatest fighter of his era. Latterly, his philandering bought him a bullet in the arm which he happily took to the ring lodged in his flesh. It made no difference to his thumping dominance.

If not, then, extraordinary commitment to training, could it be speed and power, the cornerstone of many great title reigns? Frankly, no. Monzon was a consistently hurtful puncher, especially before arthritis began to affect his hands, and he had good functional speed, but he was not fast in the sense that Robinson or Burley were.

I think what made him so difficult to beat was that supernatural engine, perhaps the definitive one for the modern middleweight division despite the abuses he heaped upon it, a machismo unparalleled and, most of all, a strategic deployment that came as close to solving boxing as anything I have ever seen.

In a nutshell, Monzon insisted upon one of two things in the ring: either that you put yourself somewhere where you would be available to be hit for three minutes of every round, (with pressure, say, or aggression), or he would put you there himself. From there, he would rely on work-rate and a consistent and resounding accuracy exemplified by one of the most dangerous jab double-right-hand combinations in history (check out his rematch with Jean Claude Bouttier for a particularly withering example).

If this sounds too simple to work, consider Monzon’s record. He didn’t pick up as many ranked scalps as Hagler, but this may be more to do with cultural bias than anything else. Perhaps the likes of Andres Selpa and Jorge Hernandez did not deserve Ring rankings but their records stood at 119-42-27 and 109-6-1 respectively when Monzon beat them during a savage apprenticeship fought in the figurative bandit-country of South America’s wild-west. And when he hit the heights of Ring’s top ten with his domination of Nino Benvenuti, foes fell to the wayside regardless of what number was propping them up at bell. He probably made Colombian puncher Rodrigo Valdes wait too long but when they met not once but twice, Monzon dropped him and bettered him. His title reign is as close to unimpeachable as it was long.

As close as his crushing excellence brought him to the #1 spot.

Other Top Fifty Middleweights Beaten: Emile Griffith (29), Nino Benvenuti (22).

#01 – HARRY GREB (107-8-3; Newspaper Decisions 155-9-15)

At first I thought Robinson would be #1. Then, when a detailed look started to make me feel that perhaps Robinson’s latter inconsistencies might hamper him, I began to favor Monzon – the greatest of the middleweight champions, after all.

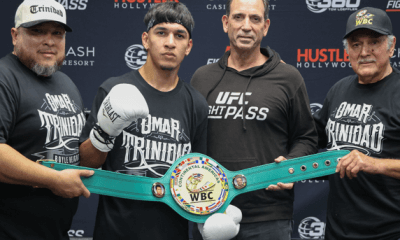

The reason I never figured Harry Greb for #1 is the same reason Mickey Walker didn’t make the top ten. Like Walker, Greb (pictured) did so much of his fighting against heavier men, victories for which he cannot be credited here. If that sounds harsh, consider that I have already credited him for them; he ranked #3 all time at light-heavyweight; he ranked #47 all-time at heavyweight; and ranked #2 all-time pound-for-pound, a ranking that may require urgent review.

So Greb, having received heaped praise for his contribution at these other weights, would, I presumed, come up short, spread too thin.

But here he is.

A key aspect in researching this series of articles has been to try to establish which fighters were ranked at the relevant poundage at or around the time they were dispatched by the subject. This is not possible for Greb as rankings as we know them were not available for most of his career. Fortunately when we research Greb, rather than measuring ranked men, we can measure all-time greats and we can measure champions. He dominated many including, incredibly, almost every man to reign as middleweight champion of the world between 1914 and 1931, from the short reign of George Chip to the abdication of Mickey Walker, excluding only himself and Mike O’Dowd with whom he boxed a draw.

His own stint started late after a round up of underwhelming title-holder Johnny Wilson in 1923 followed by a successful defense against the underrated Brian Downey. Downey is the type of fighter who is key to unlocking the Greb legacy specific to middleweight. Hardly a household name, even in his own era, he nevertheless dropped and defeated the great Mike O’Dowd, boxed a draw with the then champion Wilson after being cheated out of a win against him in their first match, received a newspaper decision over George Chip and dropped and defeated the legendary Jack Britton. Greb utterly thrashed him over ten.

Despite the distraction of wars with the likes of Gene Tunney and Kid Norfolk up at 175lbs, he nevertheless found time to defend against the deposed Wilson, another of the era’s underrated contenders Ted Moore, the monstrous Mickey Walker who he handled with absurd ease, before being unseated by Tiger Flowers in a sloppy, confused fight that reads as both close and difficult to score.

Prior to coming to the title he bested Jeff Smith in a difficult series, twice bested the great Jack Dillon, twice bested champion Al McCoy, twice bested future light-heavyweight champion Mike McTigue, and beat fellow top-ten lock Mike Gibbons.

Tempering his astonishing achievement at middleweight are the defeats he suffered to Flowers at the end of his career and a certain overlapping of series with men like Tommy Gibbons where he avenged defeat at middleweight up at light-heavyweight. Secondly, it is true that Greb, probably due to a lack of knockout punching-power and an “odd” style (think of the initial reaction to the emergence of Muhammad Ali for another example), seemed to impress the era’s boxing men less completely than the likes of Stanley Ketchel and Bob Fitzsimmons.

Those that shared the ring with him, however, are fulsome in their praise. Jack Dillon went to the astonishing lengths of questioning if there were any point in even trying against Greb while naming him so fast that “he didn’t even give me time to spit the blood out of my mouth.” Clay Turner named him “the next best man to Jack Dempsey in the world” – keep in mind that Greb was primarily weighing in at around 160lbs at this time. Gene Tunney named him the best middleweight ever to have lived and Jack O’Brien, who met both Ketchel and Fitzsimmons, named him “the greatest specimen of physical manhood in modern history.”

Nat Fleischer and Charley Rose both ranked Ketchel above Greb; but the 2005 IBRO list went for Greb as their #1. We need to be careful – as the men who saw him fade from view we need to keep an open mind as to who and what Greb was in the ring because the heart-breaking absence of footage makes interpretation a more pointed and questionable tool applied to paper history than it is when applied to film. But I welcome Greb’s new status among history buffs in this new century; welcome and embrace it as my own judgement.

Other Top Fifty Middleweights Beaten: Jeff Smith (41), Jack Dillon (19), Mickey Walker (18), Mike Gibbons (6).

For those of you who have taken the time to read this and all the other installments of my Top Fifty series, I thank you.

EDITOR’S NOTE: This article was extracted from a story that ran on this site on Oct. 21, 2015 (CLICK HERE TO VIEW IT), and then welded, with slight modifications, to the final installment of Matt McGrain’s middleweight series which appeared on Nov. 6, 2015. If you were expecting to find GGG and/or Canelo on this list, keep in mind that the list was compiled nearly five years ago. Matt McGrain writes from Scotland.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in The Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Book Review4 days ago

Book Review4 days agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoOleksandr Usyk Continues to Amaze; KOs Daniel Dubois in 5 One-Sided Rounds