Featured Articles

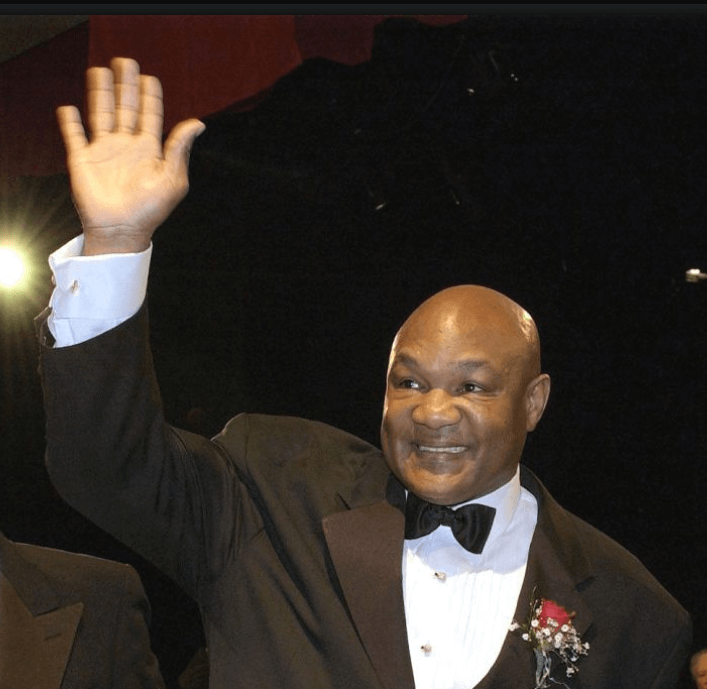

A Paean to George Foreman (1949-2025), Architect of an Amazing Second Act

George Foreman had two careers as a prizefighter. He finished his first career with a record of 45-2 and his second career with a record of 31-3.

The two careers were interrupted by a 10-year intermission. During the lacuna, George morphed seamlessly into a different person. The first George Foreman was menacing and the second George Foreman was cuddly. But in both incarnations, Foreman was larger than life. It seemed as if he would be with us forever.

George Foreman, born in 1949 in Marshall, Texas, a suburb of Houston, learned to box in the Job Corps, a federally-funded vocational training program central to President Lyndon Johnson’s anti-poverty initiative. He was already well-known when he made his pro debut in 1969 on a card at Madison Square Garden topped by an alluring contest between Joe Frazier and Jerry Quarry.

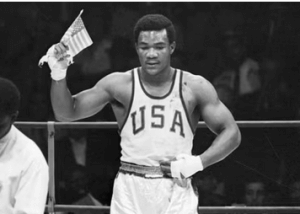

The previous year, at the Olympic Summer Games in Mexico City, George endeared himself to the vast majority of white Americans (and many African-Americans too) by parading around the ring clutching a tiny American flag in his right hand after winning his gold medal match with a second-round stoppage of his Russian opponent. The scene was viewed by millions on television and the picture of it graced the front page of many large-circulation American papers.

The image would not have resonated as strongly if not for the actions of medal-winning American sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos. Ten days earlier, at the same Summer Games, Smith and Carlos stood on the podium with their black-gloved fists clenched high in a black power salute during the playing of the National Anthem. Big George, although only 19 years old, was hailed as a patriot, an antidote to those that would tear apart (or further rent) the fabric of American society.

Foreman squandered the admiration that flowed his way with his disposition. He didn’t handle the demands of celebrityhood very well. Reporters found him stand-offish if not downright surly. But he kept winning.

Foreman was never better than on the night of Jan. 22, 1973, when he conquered defending heavyweight champion Joe Frazier in less than two rounds at Kingston, Jamaica. Frazier, like Foreman, unbeaten and a former Olympic gold medalist, was as high as a 5/1 favorite in U.S. precincts, but George demolished him. Frazier was up and down like a yo-yo, six times in all, during the brief encounter.

In his next two fights, Foreman knocked out veteran Puerto Rican campaigner Joe Roman in the opening round and took out Ken Norton in the second frame, the same Ken Norton who had fought 24 rounds with Muhammad Ali, winning and losing split decisions.

Then came the iconic Rumble in the Jungle and we know what happened there. Riding a skein of 24 wins inside the distance, Foreman entered that contest with a record of 40-0 and the prevailing sentiment among the cognoscenti was that he would horizontalize Muhammad Ali in the same fashion as he had starched most of his other victims.

Following this setback, Foreman sat out all of 1976. He would have six more fights before his goodbye starting with a bout at Caesars Palace with Ron Lyle.

Foreman bombed out Lyle in the fifth frame of a back-and-forth slugfest that would be named The Ring magazine Fight of the Year. Four more knockouts would follow beginning with a fifth-round stoppage of Joe Frazier in their second and final meeting and then came a date in San Juan with Jimmy Young, a cutie from Philadelphia.

Foreman and Young met on a sultry afternoon in March of 1977 at the Roberto Clemente Coliseum, a building with no air-conditioning. Foreman nearly took Young out in the seventh round of the 12-round contest but ran out of gas and lost a unanimous decision.

In his dressing room after the fight, Foreman experienced an epiphany and became a born-again Christian. His trainer Gil Glancy rationalized the voices that Foreman heard in his head as a hallucination born of heat prostration, but George was having none of it. He returned to Houston where he could be found evangelizing on street corners or preaching as a guest pastor in storefront churches. His Rolls Royce was gone, replaced by a Volkswagen, and he found coveralls more to his liking than the fancy silk suits he had once purchased in bulk. He eventually established his own church, the Church of Lord Jesus Christ, and became an ordained minister.

ACT TWO

F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote, “There are no second acts in American lives,” but Fitzgerald never met Reverend George Foreman.

Foreman’s second act began on March 9, 1987, before an announced crowd of 5,555 at Arco Arena in Sacramento with a fourth-round stoppage of journeyman Steve Zouski. He told reporters in attendance that he would use his purse, reportedly $24,000, to build a youth center but the cynics were of the opinion that every penny would go into his coffers as expensive divorces and other burdens had exhausted his savings. When George passed the collection plate at his church, wisecracked the wiseguys, all that came back was lint.

Although Foreman had been out of action for a decade, it seemed much longer. By then, Muhammad Ali had fallen into decrepitude, dating an entire generation of heavyweights as relics. In appearance and in fighting style, Foreman scarcely resembled his former self which had the sensory effect of elongating the gap in his timeline. The new George Foreman shaved his head bald and his torso was more massive. When he sallied out of his dressing room, Hall of Fame boxing writer Graham Houston likened the impression to that of an ancient battleship coming out of the mist.

This reporter was ringside for Foreman’s second comeback fight at the Oakland Coliseum where he was paired against Charles Hostetter, a smallish heavyweight packaged as the heavyweight champion of Texas. Hostetter folded his tent in the third round, taking a knee like a quarterback running out the clock at the end of a football game. Foreman carried 247 pounds, 20 pounds less than what he had carried for Zouski but nearly 30 pounds more than what he had carried in his first meeting with Joe Frazier.

The Hostetter fight was a set-up, as were many of Foreman’s fights in the first two years of his comeback, but Big George never cheated himself. Away from the probing eye of reporters, he always went the extra mile in his workouts.

Foreman stayed busy, but his comeback proceeded in fits and starts. In his eighth comeback fight, he stopped Dwight Muhammad Qawi in the seventh round (more exactly, Qawi quit, turning his back on the referee to signal that he was finished) at Caesars Palace, but it was a lackluster performance by George whose punches were slow and often missed the mark. This was the same Dwight Muhammad Qawi who had given Evander Holyfield a tough tussle in a 15-round barnburner when both were cruiserweights, but against Foreman the “Camden Buzzsaw” was a bloated butterball, carrying 222 pounds on his five-foot-seven frame.

The bout’s promoter, Bob Arum, exhorted Foreman go back to the bushes to freshen-up and when George returned to the ring nine weeks later it was in Alaska in an off-TV fight against an opponent with a losing record.

But Foreman’s confidence never wavered and when he finally lured a big-name opponent into the ring, Gerry Cooney, he was more than ready. They met on Jan. 16, 1990, at Boardwalk Hall in Atlantic City.

At age 33, Cooney was also on the comeback trail. He hadn’t fought in two-and-half years, not since being stopped in the fifth round by Michael Spinks in this same ring. Since his mega-fight with Larry Holmes in mid-1982, he had answered the bell for only 12 rounds. But, rusty or not, Cooney still possessed a sledgehammer of a left hook.

Cooney landed the harder punches in the first round and won the round on all three cards, but Big George was just warming up. In the second stanza, he decked Cooney twice. The second knockdown was so harsh that referee Joe Cortez waived the fight off without starting a count.

“He smote him,” wrote Phil Berger for his story in the New York Times. “The Punching Preacher gained a flock of converts,” said Bernard Fernandez in the Philadelphia Daily News.

Foreman called out Mike Tyson after the fight. The wheels were set in motion when they shared top billing on a card at Caesars Palace in June of 1990 (Tyson knocked out former amateur rival Henry Tillman in the opening round; Foreman dismissed the Brazilian, Adilson Rodrigues, in round two), but the match never did come to fruition and Foreman, tired of waiting, set his sights on Evander Holyfield who owned two of the three meaningful pieces of the world heavyweight title.

An Adonis-physiqued gladiator renowned for his vitality, Holyfield, 28, figured to be too good and too fast for Foreman. If Evander set a fast pace, Foreman, it seemed, would eventually crumble from exhaustion. “Hopefully Holyfield will take it easy on him,” wrote the sports editor of the Tennessean. “There’s no glory to be gained in mugging a senior citizen.”

Holyfield won the fight, but Foreman – the oldest man to challenge for a world title in any weight division to that point in time — won the hearts of America with his buoyant performance. On several occasions Holyfield rattled him, but Big George kept coming back for more and at the finish it was he, improbably, who seemed to have more fuel in his tank. After trouncing Gerry Cooney, casual fans, at least most of them, finally took him seriously and with his gallant performance against Holyfield, he graduated into a full-fledged American folk hero. One would be hard-pressed to find an example of a boxer elevating his stature to such an extent in a match that he lost.

There was more to George Foreman’s growing popularity. He proved to be a great salesman, leavening his fistic fearsomeness with self-effacing humor. He developed an amusing shtick that played off his fondness for cheeseburgers and he became a popular guest on the talk show circuit. “Is this Adilson Rodrigues a good fighter?” inquired Johnny Carson. “I sure hope not,” deadpanned Foreman.

History would show that Big George wasn’t done making miracles, but there were potholes in his path. He had ended the Holyfield fight with a puffy face and with swelling around both of his eyes, but he looked a lot worse following his 10-round match with Alex Stewart in April of 1992. At the final bell, his face was a bloody mess and both of his eyes were swollen nearly shut. Fortunately, he scored two knockdowns in the second stanza, without which he would have been on the wrong side of a split decision.

Two fights later, he was out-pointed by Tommy Morrison in a bout sanctioned as a world title fight by the fledgling and lightly-regarded World Boxing Organization (WBO). Purportedly a distant relative of John Wayne, “Tommy the Duke” had the equalizer, a Cooney-ish left hook, but there were holes in his defense. A slugfest on paper, this bout played out like a chess match. Go figure.

Eighteen months after his lackluster showing against Morrison, Foreman got another shot at the world heavyweight title, thrust against Michael Moorer who had upset Holyfield to win the WBA and IBF (and lineal) titles. (The WBC version was held by Lennox Lewis; Mike Tyson was in prison.) A former light heavyweight champion who had successfully defended that diadem nine times, Moorer, not quite 27 years old, was undefeated in 35 fights with 30 knockouts.

The match-up was widely disparaged because of the alphabet soup nonsense and because Foreman was coming off a loss. “Big George has been good for the game, but has outstayed his welcome,” wrote Harry Mullen. The noted British scribe, who had been ringside for Larry Holmes’ beatdown of Muhammad Ali, told his readers that he wouldn’t be going to Las Vegas to see the fight because he just couldn’t stomach yet another dispiriting spectacle. “The most likely outcome,” he said, “is a prolonged and painful beating.”

At this juncture of his life, Foreman didn’t need the money. Although his TV sitcom “George” had been cancelled after only eight episodes (George played a retired boxer who starts an after-school program for inner-city kids), he had money rolling in from a slew of endorsements. McDonald’s, KFC, Frito-Lay, Oscar Meyer – you name it – and Big George was a “brand ambassador.” With his purse of no great importance in the big picture, George’s only incentive for defeating Moorer was his pride.

Through nine rounds, Moorer vs. Foreman was a tedious affair. Moorer was ahead by a commanding 5 points on two of the scorecards while the third judge had Moorer ahead by only 1. Foreman, who scored 68 knockouts over the course of his pro career, always had a puncher’s chance, no matter the opponent, but there was no inkling of the thunderclap that would come. This was shaping up as the sort of fight that would have the patrons streaming to the exits before the final bell.

The thunderclap arrived in the final minute of the 10th frame. It was a classic British punch in execution, a stiff right hand delivered straight from the shoulder. The punch didn’t travel far, but landed smack on Moorer’s jaw. His face went blank and he fell to the canvas where he lay prone as the referee counted him out. Before the stupefied crowd had a chance to soak it all in, Foreman dropped to his knees in prayer. Many were misty-eyed as ring announcer Michael Buffer made it formal, orating the particulars.

Six days after the 20th anniversary of the Rumble in the Jungle, Big George Foreman had rolled back the clock, recapturing the world heavyweight title, or at least pieces of it, capping the most astonishing comeback in the history of human endurance sports.

Foreman would have four more fights before leaving the sport for good two months shy of his 49th birthday. We won’t delve into those bouts other than noting that he was fortunate to get the nod over Axel Schulz and unfortunate to lose to Shannon Briggs in his farewell fight, a narrow decision widely assailed as a heist.

And the money kept rolling in. In 1994, the year that Foreman conquered Michael Moorer, a portable indoor grill that came to be called the George Foreman Lean Mean Fat Reducing Grilling Machine was introduced to the public. The contraption proved so popular that Foreman, the TV pitchman and the face of it, reaped a reported $200 million in royalties, more money than he had earned in all of his prizefights combined.

They say you can never go home again, to which Big George replied , “bah, humbug.”

Foreman’s heroics during his Second Act put a spring my step and had the same effect on many others. In the words of the inimitable Jim Murray, he was a hero to every middle-aged man and older who looked in the mirror and saw some stranger looking back at him.

Thank you, George, thanks for the memories. Rest in peace

***

Note: TSS editor-in-chief Arne K. Lang is the author of five books including “Prizefighting: An American History,” released by McFarland in 2016 and re-released in a paperback edition in 2020. Several of the passages in this story were extracted from that book.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 330: Matchroom in New York plus the Latest on Canelo-Crawford

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoVito Mielnicki Jr Whitewashes Kamil Gardzielik Before the Home Folks in Newark

-

Featured Articles23 hours ago

Featured Articles23 hours agoResults and Recaps from New York Where Taylor Edged Serrano Once Again

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoCatching Up with Clay Moyle Who Talks About His Massive Collection of Boxing Books

-

Featured Articles5 days ago

Featured Articles5 days agoFrom a Sympathetic Figure to a Pariah: The Travails of Julio Cesar Chavez Jr

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoMore Medals for Hawaii’s Patricio Family at the USA Boxing Summer Festival

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoCatterall vs Eubank Ends Prematurely; Catterall Wins a Technical Decision

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRichardson Hitchins Batters and Stops George Kambosos at Madison Square Garden