Featured Articles

Is Kosei Tanaka the World’s Brightest Prospect?

By my reckoning Naoya Inoue was the prospect of the year in January 2013 and the fighter of the year by January 2015; that is an astonishing rate of development. The temptation when a major force of boxing potential is born outside the United States is to ask, “He looks good, but will he travel well?”

But like the top British fighters, top Japanese don’t have to travel at all. They can make a lifetime of money boxing on their own shores. Where the Japanese differ from the British is in their ability to buy in the very best fighters from the rest of the world to provide the sternest tests for their potential conquistadors at home. Bringing the world’s #1 minimumweight Adrian Hernandez and the #1 junior bantamweight Omar Narvaez to Japan in order that they may suffer Naoya’s tender attentions has made him one of the feared fighters in the world with his professional record just 8-0 and at the age of just twenty-one. A Japanese prospect with world-class potential is not “held back”, is not allowed to “gain experience” and is not permitted to “get rounds under their belt.” Instead, they fight the best their fledging abilities allow.

Nineteen years of age with a professional record of just 4-0, Kosei Tanaka will probably fight a ranked opponent for an alphabet strap in 2015. A minimumweight, he has already been scheduled for twelve rounds in a fight that went ten, and he has never indulged in the traditional four round encounters that buoy prospects concerned about fitness and stamina. Even compared to Naoya he is ahead of the absurd learning curve set for the best Japanese prospects, so much so that if we don’t take a detailed look at him now, at just four fights, we will likely be looking at a contender or strapholder rather than a prospect. So here is a tentative breakdown of how good this teenager is – and just how good he might become.

Style

Tanaka is a box-mover in the truest sense, a methodology designed to embrace to the greatest extent his natural gifts. In danger of becoming a national style in Japan, it works well for any fighter with the necessary speed, stamina and temperament, and it forms the first line of defence for a fighter capable of its execution. Tanaka’s default style is one of retreat, but he is moving away in narrow circles, moving the opponent into range rather than moving himself out of it. While it forms a natural barrier to opposition forages, it also calls for a high degree of judgment and discipline and an ability to recognise viable openings in accordance with the fighter’s own physical abilities. Fortunately, Tanaka is naturally aggressive. Married to this mobile style is a spiteful determination to fight which happily bridges the gap between not enough and too much.

An accomplished amateur without being storied or draped in gold, he bested the much-hyped younger Inoue brother, Takuma, overall in their several unpaid encounters – but little of the amateur remains. Perhaps lacking a little in the fluidity and improvisational skill he now displays, it is nevertheless clear that despite the pillows and the headgear, Takuma’s brief stay in the amateurs was used not as a springboard to an Olympic gold medal but in the old fashioned way: to hone a professional.

Balance and Footwork

It is not a particularly interesting nor an insightful thing to say, but Tanaka’s balance is already elite. In his first fight he was matched with Oscar Raknafa, a fighter who moved up to flyweight and embraced a sad fate as a professional loser, but at minimumweight had never been stopped and had been the national champion of Indonesia for a year before gaining a regional strap. He was far from typical as a debut opponent, even for an elite prospect. Winning every one of the six rounds, Tanaka also dropped Raknafa in the first with a beautiful combination born first and foremost of his ability to make a punching out of movement.

Winning every one of the six rounds, Tanaka also dropped Raknafa in the first with a beautiful combination born first and foremost of his ability to create punching opportunities with movement alone.

On no notice he can dip through his right knee to support a firecracker right hand, as he did with thirty seconds departed of round two in the same fight, but he also has the skill in footwork to augment his balanced offence, using steps to escape again in a tight circle. This bobbing, mobile style is a variation of what made Manny Pacquiao so dangerous, and although those comparisons begin and end right there, the boy moves well enough that it is a valid one.

The only concern in this department is a possible lack of economy. If Tanaka has to fight defensively or force a lead he will be forced to take many more steps than his opponent to do so. Does he have the engine for it, and if he does, will he carry his power late enough for it to matter?

Technique on Defence

The choice for Tanaka’s second professional opponent was fascinating to me. The man who got the nod was Ronelle Ferreras (13-6-2 going in), a twenty-eight year old Filipino with a great jaw and a line in losing whenever he stepped up in class. A typical opponent then for most prospects bowed by the weight of the tag “future world champion” but what set Ferreras apart was that he was a southpaw. The only film in existence of Tanaka really struggling is against a southpaw, an amateur and 2014 Asian Youth Games bronze medallist, Erdenebat Tsendbaatar out of Mongolia. Tsendbaatar walked Tanaka onto repeated straight left hands out of the southpaw stance, and although Tanaka was never in trouble, nor discouraged, he was caught flush on several occasions.

Defensively, Tanaka uses movement and a disciplined high-guard to make him hard to hit, but he is no Cuban exile – he is a Japanese stylist and as such he comes to fight and inevitably will be, at times, there to be hit. If Ferreras was able to take advantage of a stylistic predisposition to violence in combination with a possible weakness against the southpaw left, perhaps he would be able to trouble Tanaka.

In reality, he hardly landed a straight left hand all night. Most of his success occurred on the inside, where Tanaka’s tightly regulated guard smothered most of his work. The Japanese ducked and stepped away from most of the Filipino’s offence on the outside while unleashing his latest pet punch, a caning right hand to the body.

It is a body attack to which he may be most vulnerable himself but he has never looked close to being overwhelmed against either good amateur competition or limited professional competition – although, I think Ryuji Hara hurt him with a body shot in the ninth round of their contest from October of last year. Despite that, the movement upon which his style is founded should lend him some protection.

This naturally occurring defence is an enormous boon for an aggressive young fighter and although some more advanced punch-picking wouldn’t hurt, his defence is essentially in line with his style, having improved dramatically since his amateur days.

Technique on Offence

Tanaka is brilliant on offence. Even before he turned professional a commitment to a withering body-attack and a sure fluidity at all ranges marked him out as a fighter destined to make a splash as a professional. That said, his inability to stop Ferreras or Raknafa despite dominating performances did make me wonder about the kid from Nagoya. His absurd first round knockout of Crison Omayao was the perfect tonic.

Omayao was the debut opponent for the devastating Naoya Inoue, a fight in which he managed no fewer than four rounds. Tanaka took him out in less than two minutes and he did it using his right, which looked the technically weaker of the two hands up until that point. Not that the finishing punches were necessarily textbook, but rather the type of marauding, booming crushers more suited to a heavyweight journeyman on the make. The end result was a stupefied Omayao regaining his feet but loose-limbed and vacant, staring across the ring as though confronted by the avenging angel itself. The referee took a brief look and then waved off the only fight that allows a direct comparison between Tanaka and Naoya, a comparison that on paper finds Naoya wanting.

His left hand is a thing of wonder. Against Raknafa he landed a left-hook double-jab combination to set up the brutalising right hand in the literal blink of an eye; it’s a can-opener of a punch, the rapier to the right-hand bazooka, two weapons that complement each other perfectly. Combinations beyond the reach of eight year professionals are at his fingertips.

A very healthy habit of adding punches with each successive fight can come to an end without further evolution and leave behind a varied attack based upon a snapping jab that unlocks a wide reserve of power punches. Great offence, when it evolves, tends to be based upon great punch selection, swift persistence in throwing or a combination of the two; Tanaka falls happily into this final category.

Temperament and Generalship

Generalship is a natural gift of Tanaka’s style. It provides a natural control over territory via small-moves ring-centre and the only way to challenge him directly is with a head on assault that rather plays into his style on offence, or a retreat, always a compromise on the scorecards and an invitation to measure pure technical ability with a fighter who looks to be a near world-class technician after just four fights. The flip side of this gold coin is tarnished by a necessity for patience and for the discipline to stick to a naturalised gameplan regardless of provocation.

Precious film of one of Tanaka’s confrontations with Takuma Inoue in the amateurs provides an answer to the question of whether Tanaka is this sort of man affirmatively. Inoue looks faster, stronger and more aggressive in the opening rounds of this contest, and although Tanaka appears already to be the more technically proficient the sheer pace at which the contest is being hustled sees him miss plenty of punches. Tanaka does not panic. He just sticks to his boxing and by the end of the third round the faster, more aggressive Takuma has been handled, is giving ground and getting hit.

Professionally he showed great patience in returning to his boxing after dropping Raknafa and in outwaiting and outfighting Hara. The pressure on this young man’s shoulders is incredible, the weight of expectation severe. All the outward signs are that he is equal to it.

Punch Resistance and Stamina

It is unusual for a four-fight professional to provide much in the way of evidence one way or the other in these categories, but Tanaka’s advancement has been so swift that we can draw certain tentative conclusions.

In his fourth fight, he met 18-0 prospect Ryuji Hara. Hara is an excellent talent, a fluid puncher with fast hands and a nice line in two piece combinations that often end in body punches. Tanaka dropped a handful of frames on the way to stopping him in the tenth round of a fight that demonstrated his ability to fight at pace and retain his power into the late rounds.

Despite having a fraction of his opponent’s experience over longer distances and despite having suffered the unwanted attentions of Hara’s violent body-attack, Tanaka was far the fresher man down the straight. His footwork was undiminished, his reactions were unimpaired, and although he sought to rest once in the eighth and once in the ninth, his output was basically unaffected. The end of the ninth and the beginning of the tenth was something of a zenith in Tanaka’s fledgling career – in the final minutes of a hard fight, he absolutely poured on punches for a stoppage that was a mercy.

Hara also landed his own punches during savage, lightning exchanges but one or two body shots aside, I was of the impression that Tanaka was never caught absolutely clean by the romping offence coming his way. This hints at superb radar, but doesn’t help in appraising the fighter’s chin. I turned to Asianboxing.com’s Takahiro Onaga for a second opinion.

“As a professional, no I don’t think he has been properly chin-checked,” offered Takahiro. “However, he’s never seemed bothered being tagged, and has shown a willingness to mix it up as and when he chooses. I suspect he’s very confident in his [chin].”

I agree, and this is reassuring – but like every potential champion, his moment of truth lies ahead.

Speed and Power

Tanaka is fast. Because he has a rangy feel and boxes tall, there is a sense that he might come second against the very fastest fighters in a straight-up quick-draw, but I am not entirely convinced there is any fighter in the world that puts together combinations faster. He is blindingly fast between punches and the fourth is as fast as the first.

In terms of his hitting power I have reservations. In his debut against Raknafa, he couldn’t get the stoppage despite landing punches with impunity. While it is true that Raknafa had never been stopped, he has been since – in fact, he’s been stopped in every outing since Tanaka in seven, six and four rounds against decent flyweight opposition. Presuming Tanaka did not break him (which seems premature), what this tells us is that on his debut, Tanaka did not have power that could rank him a puncher at flyweight. At nineteen years of age, flyweight is where he is eventually headed – if this read is accurate, he will not rate a knockout artist there.

His technique is superb and I can’t imagine an augmentation adding pounds per square inch, but he might get more power in line with weight gain. This is the best he could hope for I think, and it would make him a dangerous puncher. This could lead to many accumulation stoppages, but I don’t think he will ever be the kind of fighter to be rescued by his power.

Next

“There is no beef,” Takahiro told me in answer to my question about Tanaka and the Inoue brothers. “They are said to be somewhat friendly. I suspect they have a general respect for each other.”

Nevertheless, it is likely that the paths of one or both the Inoue brothers converge with that of Tanaka at some point in the near future. In the meantime, Wanheng Menayothin has been made the primary target for team Tanaka. The #2 ranked minimumweight is the holder of a belt and seemingly available, although a dominant performance against the unbeaten Jeff Galero may have made Katsunari Takayama and a Japanese superfight the more attractive option. Either way, Tanaka is looking at a major step up as early as his very next fight.

Personally, I make him a favourite to beat either of them.

Featured Articles

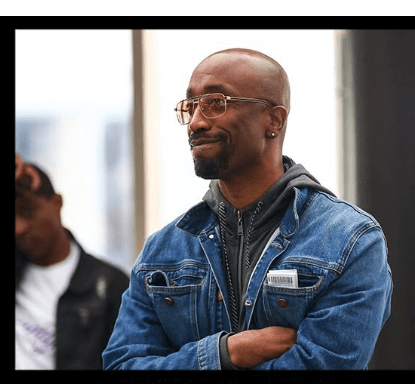

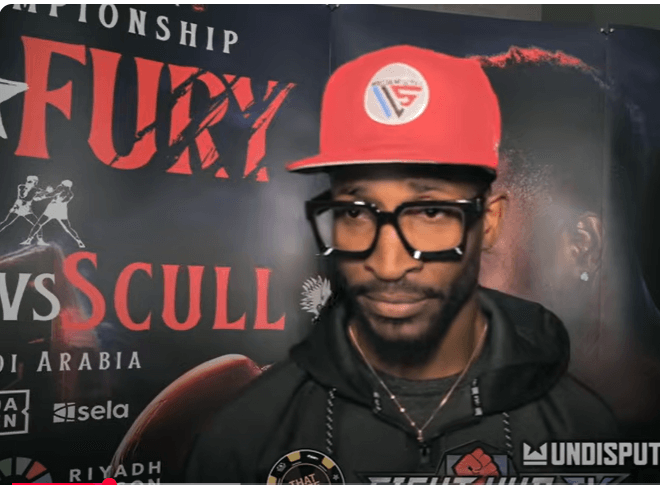

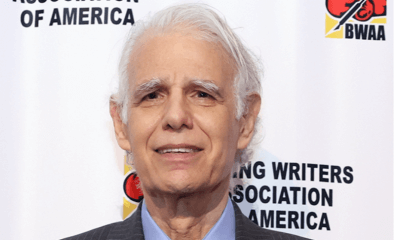

“Breadman” Edwards: An Unlikely Boxing Coach with a Panoramic View of the Sport

Stephen “Breadman” Edwards’ first fighter won a world title. That may be some sort of record.

It’s true. Edwards had never trained a fighter, amateur or pro, before taking on professional novice Julian “J Rock” Williams. On May 11, 2019, Williams wrested the IBF 154-pound world title from Jarrett Hurd. The bout, a lusty skirmish, was in Fairfax, Virginia, near Hurd’s hometown in Maryland, and the previously undefeated Hurd had the crowd in his corner.

In boxing, Stephen Edwards wears two hats. He has a growing reputation as a boxing coach, a hat he will wear on Saturday, May 31, at Mandalay Bay in Las Vegas when the two fighters that he currently trains, super middleweight Caleb Plant and middleweight Kyrone Davis, display their wares on a show that will air on Amazon Prime Video. Plant, who needs no introduction, figures to have little trouble with his foe in a match conceived as an appetizer to a showdown with Jermall Charlo. Davis, coming off his career-best win, an upset of previously undefeated Elijah Garcia, is in tough against fast-rising Cuban prospect Yoenli Hernandez, a former world amateur champion.

Edwards’ other hat is that of a journalist. His byline appears at “Boxing Scene” in a column where he answers questions from readers.

It’s an eclectic bag of questions that Breadman addresses, ranging from his thoughts on an upcoming fight to his thoughts on one of the legendary prizefighters of olden days. Boxing fans, more so than fans of any other sport, enjoy hashing over fantasy fights between great fighters of different eras. Breadman is very good at this, which isn’t to suggest that his opinions are gospel, merely that he always has something provocative to add to the discourse. Like all good historians, he recognizes that the best history is revisionist history.

“Fighters are constantly mislabled,” he says. “Everyone talks about Joe Louis’s right hand. But if you study him you see that his left hook is every bit as good as his right hand and it’s more sneaky in terms of shock value when it lands.”

Stephen “Breadman” Edwards was born and raised in Philadelphia. His father died when he was three. His maternal grandfather, a Korean War veteran, filled the void. The man was a big boxing fan and the two would watch the fights together on the family television.

Edwards’ nickname dates to his early teen years when he was one of the best basketball players in his neighborhood. The derivation is the 1975 movie “Cornbread, Earl and Me,” starring Laurence Fishburne in his big screen debut. Future NBA All-Star Jamaal Wilkes, fresh out of UCLA, plays Cornbread, a standout high school basketball player who is mistakenly murdered by the police.

Coming out of high school, Breadman had to choose between an academic scholarship at Temple or an athletic scholarship at nearby Lincoln University. He chose the former, intending to major in criminal justice, but didn’t stay in college long. What followed were a succession of jobs including a stint as a city bus driver. To stay fit, he took to working out at the James Shuler Memorial Gym where he sparred with some of the regulars, but he never boxed competitively.

Over the years, Philadelphia has harbored some great boxing coaches. Among those of recent vintage, the names George Benton, Bouie Fisher, Nazeem Richardson, and Bozy Ennis come quickly to mind. Breadman names Richardson and West Coast trainer Virgil Hunter as the men that have influenced him the most.

We are all a product of our times, so it’s no surprise that the best decade of boxing, in Breadman’s estimation, was the 1980s. This was the era of the “Four Kings” with Sugar Ray Leonard arguably standing tallest.

Breadman was a big fan of Leonard and of Leonard’s three-time rival Roberto Duran. “I once purchased a DVD that had all of Roberto Duran’s title defenses on it,” says Edwards. “This was a back before the days of YouTube.”

But Edwards’ interest in the sport goes back much deeper than the 1980s. He recently weighed in on the “Pittsburgh Windmill” Harry Greb whose legend has grown in recent years to the point that some have come to place him above Sugar Ray Robinson on the list of the greatest of all time.

“Greb was a great fighter with a terrific resume, of that there is no doubt,” says Breadman, “but there is no video of him and no one alive ever saw him fight, so where does this train of thought come from?”

Edwards notes that in Harry Greb’s heyday, he wasn’t talked about in the papers as the best pound-for-pound fighter in the sport. The boxing writers were partial to Benny Leonard who drew comparisons to the venerated Joe Gans.

Among active fighters, Breadman reserves his highest praise for Terence Crawford. “Body punching is a lost art,” he once wrote. “[Crawford] is a great body puncher who starts his knockouts with body punches, but those punches are so subtle they are not fully appreciated.”

If the opening line holds up, Crawford will enter the ring as the underdog when he opposes Canelo Alvarez in September. Crawford, who will enter the ring a few weeks shy of his 38th birthday, is actually the older fighter, older than Canelo by almost three full years (it doesn’t seem that way since the Mexican redhead has been in the public eye so much longer), and will theoretically be rusty as 13 months will have elapsed since his most recent fight.

Breadman discounts those variables. “Terence is older,” he says, “but has less wear and tear and never looks rusty after a long layoff.” That Crawford will win he has no doubt, an opinion he tweaked after Canelo’s performance against William Scull: “Canelo’s legs are not the same. Bud may even stop him now.”

Edwards has been with Caleb Plant for Plant’s last three fights. Their first collaboration produced a Knockout of the Year candidate. With one ferocious left hook, Plant sent Anthony Dirrell to dreamland. What followed were a 12-round setback to David Benavidez and a ninth-round stoppage of Trevor McCumby.

Breadman keeps a hectic schedule. From Monday through Friday, he’s at the DLX Gym in Las Vegas coaching Caleb Plant and Kyrone Davis. On weekends, he’s back in Philadelphia, checking in on his investment properties and, of greater importance, watching his kids play sports. His 14-year-old daughter and 12-year-old son are standout all-around athletes.

On those long flights, he has plenty of time to turn on his laptop and stream old fights or perhaps work on his next article. That’s assuming he can stay awake.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

Featured Articles

Arne’s Almanac: The Good, the Bad, and the (Mostly) Ugly; a Weekend Boxing Recap and More

Arne’s Almanac: The Good, the Bad, and the (Mostly) Ugly; a Weekend Boxing Recap and More

It’s old news now, but on back-to-back nights on the first weekend of May, there were three fights that finished in the top six snoozefests ever as measured by punch activity. That’s according to CompuBox which has been around for 40 years.

In Times Square, the boxing match between Devin Haney and Jose Carlos Ramirez had the fifth-fewest number of punches thrown, but the main event, Ryan Garcia vs. Rolly Romero, was even more of a snoozefest, landing in third place on this ignoble list.

Those standings would be revised the next night – knocked down a peg when Canelo Alvarez and William Scull combined to throw a historically low 445 punches in their match in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 152 by the victorious Canelo who at least pressed the action, unlike Scull (pictured) whose effort reminded this reporter of “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof” – no, not the movie starring Paul Newman, just the title.

CompuBox numbers, it says here, are best understood as approximations, but no amount of rejiggering can alter the fact that these three fights were stinkers. Making matters worse, these were pay-per-views. If one had bundled the two events, rather than buying each separately, one would have been out $90 bucks.

****

Thankfully, the Sunday card on ESPN from Las Vegas was redemptive. It was just what the sport needed at this moment – entertaining fights to expunge some of the bad odor. In the main go, Naoya Inoue showed why he trails only Shohei Ohtani as the most revered athlete in Japan.

Throughout history, the baby-faced assassin has been a boxing promoter’s dream. It’s no coincidence that down through the ages the most common nickname for a fighter – and by an overwhelming margin — is “Kid.”

And that partly explains Naoya Inoue’s charisma. The guy is 32 years old, but here in America he could pass for 17.

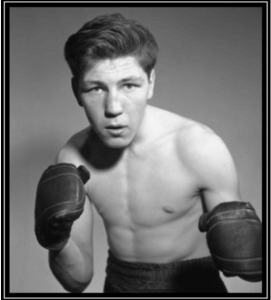

Joey Archer

Joey Archer, who passed away last week at age 87 in Rensselaer, New York, was one of the last links to an era of boxing identified with the nationally televised Friday Night Fights at Madison Square Garden.

Joey Archer

Archer made his debut as an MSG headliner on Feb. 4, 1961, and had 12 more fights at the iconic mid-Manhattan sock palace over the next six years. The final two were world title fights with defending middleweight champion Emile Griffith.

Archer etched his name in the history books in November of 1965 in Pittsburgh where he won a comfortable 10-round decision over Sugar Ray Robinson, sending the greatest fighter of all time into retirement. (At age 45, Robinson was then far past his peak.)

Born and raised in the Bronx, Joey Archer was a cutie; a clever counter-puncher recognized for his defense and ultimately for his granite chin. His style was embedded in his DNA and reinforced by his mentors.

Early in his career, Archer was domiciled in Houston where he was handled by veteran trainer Bill Gore who was then working with world lightweight champion Joe Brown. Gore would ride into the Hall of Fame on the coattails of his most famous fighter, “Will-o’-the Wisp” Willie Pep. If Joey Archer had any thoughts of becoming a banger, Bill Gore would have disabused him of that notion.

In all honesty, Archer’s style would have been box office poison if he had been black. It helped immensely that he was a native New Yorker of Irish stock, albeit the Irish angle didn’t have as much pull as it had several decades earlier. But that observation may not be fair to Archer who was bypassed twice for world title fights after upsetting Hurricane Carter and Dick Tiger.

When he finally caught up with Emile Griffith, the former hat maker wasn’t quite the fighter he had been a few years earlier but Griffith, a two-time Fighter of the Year by The Ring magazine and the BWAA and a future first ballot Hall of Famer, was still a hard nut to crack.

Archer went 30 rounds with Griffith, losing two relatively tight decisions and then, although not quite 30 years old, called it quits. He finished 45-4 with 8 KOs and was reportedly never knocked down, yet alone stopped, while answering the bell for 365 rounds. In retirement, he ran two popular taverns with his older brother Jimmy Archer, a former boxer who was Joey’s trainer and manager late in Joey’s career.

May he rest in peace.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

Featured Articles

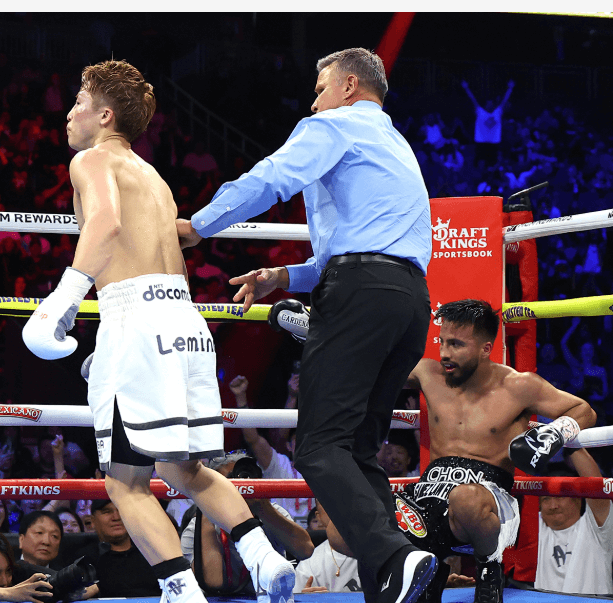

Bombs Away in Las Vegas where Inoue and Espinoza Scored Smashing Triumphs

Japan’s Naoya “Monster” Inoue banged it out with Mexico’s Ramon Cardenas, survived an early knockdown and pounded out a stoppage win to retain the undisputed super bantamweight world championship on Sunday.

Japan and Mexico delivered for boxing fans again after American stars failed in back-to-back days.

“By watching tonight’s fight, everyone is well aware that I like to brawl,” Inoue said.

Inoue (30-0, 27 KOs), and Cardenas (26-2, 14 KOs) and his wicked left hook, showed the world and 8,474 fans at T-Mobile Arena in Las Vegas that prizefighting is about punching, not running.

After massive exposure for three days of fights that began in New York City, then moved to Riyadh, Saudi Arabia and then to Nevada, it was the casino capital of the world that delivered what most boxing fans appreciate- pure unadulterated action fights.

Monster Inoue immediately went to work as soon as the opening bell rang with a consistent attack on Cardenas, who very few people knew anything about.

One thing promised by Cardenas’ trainer Joel Diaz was that his fighter “can crack.”

Cardenas proved his trainer’s words truthful when he caught Inoue after a short violent exchange with a short left hook and down went the Japanese champion on his back. The crowd was shocked to its toes.

“I was very surprised,” said Inoue about getting dropped. ““In the first round, I felt I had good distance. It got loose in the second round. From then on, I made sure to not take that punch again.”

Inoue had no trouble getting up, but he did have trouble avoiding some of Cardenas massive blows delivered with evil intentions. Though Inoue did not go down again, a look of total astonishment blanketed his face.

A real fight was happening.

Cardenas, who resembles actor Andy Garcia, was never overly aggressive but kept that left hook of his cocked and ready to launch whenever he saw the moment. There were many moments against the hyper-aggressive Inoue.

Both fighters pack power and both looked to find the right moment. But after Inoue was knocked down by the left hook counter, he discovered a way to eliminate that weapon from Cardenas. Still, the Texas-based fighter had a strong right too.

In the sixth round Inoue opened up with one of his lightning combinations responsible for 10 consecutive knockout wins. Cardenas backed against the ropes and Inoue blasted away with blow after blow. Then suddenly, Cardenas turned Inoue around and had him on the ropes as the Mexican fighter unloaded nasty combinations to the body and head. Fans roared their approval.

“I dreamed about fighting in front of thousands of people in Las Vegas,” said Cardenas. “So, I came to give everything.”

Inoue looked a little surprised and had a slight Mona Lisa grin across his face. In the seventh round, the Japanese four-division world champion seemed ready to attack again full force and launched into the round guns blazing. Cardenas tried to catch Inoue again with counter left hooks but Inoue’s combos rained like deadly hail. Four consecutive rights by Inoue blasted Cardenas almost through the ropes. The referee Tom Taylor ruled it a knockdown. Cardenas beat the count and survived the round.

In the eighth round Inoue looked eager to attack and at the bell launched across the ring and unloaded more blows on Cardenas. A barrage of 14 unanswered blows forced the referee to stop the fight at 45 seconds of round eight for a technical knockout win.

“I knew he was tough,” said Inoue. “Boxing is not that easy.”

Espinoza Wins

WBO featherweight titlist Rafael Espinosa (27-0, 23 KOs) uppercut his way to a knockout win over Edward Vazquez (17-3, 4 KOs) in the seventh round.

“I wanted to fight a game fighter to show what I am capable,” said Espinoza.

Espinosa used the leverage of his six-foot, one-inch height to slice uppercuts under the guard of Vazquez. And when the tall Mexican from Guadalajara targeted the body, it was then that the Texas fighter began to wilt. But he never surrendered.

Though he connected against Espinoza in every round, he was not able to slow down the taller fighter and that allowed the Mexican fighter to unleash a 10-punch barrage including four consecutive uppercuts. The referee stopped the fight at 1:47 of the seventh round.

It was Espinoza’s third title defense.

Photo credit: Mikey Williams / Top Rank

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

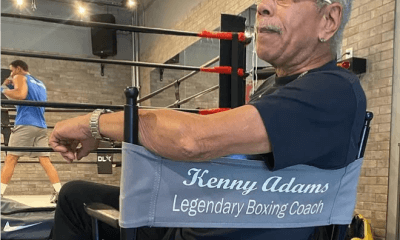

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRemembering Hall of Fame Boxing Trainer Kenny Adams

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoJaron ‘Boots’ Ennis Wins Welterweight Showdown in Atlantic City

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoBoxing Notes and Nuggets from Thomas Hauser

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective Chap 320: Boots Ennis and Stanionis

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

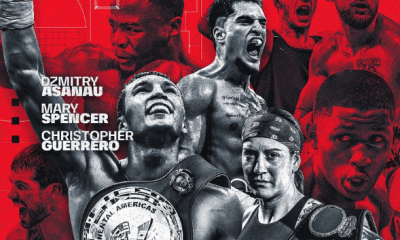

Featured Articles4 weeks agoDzmitry Asanau Flummoxes Francesco Patera on a Ho-Hum Card in Montreal

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoMekhrubon Sanginov, whose Heroism Nearly Proved Fatal, Returns on Saturday

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 322: Super Welterweight Week in SoCal

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoTSS Salutes Thomas Hauser and his Bernie Award Cohorts