Featured Articles

The Fifty Greatest Light-Heavyweights of All Time Part One – 50-41

Constructing a top 100 pound-for-pound was a difficult task, but far more tortuous was my attempt last year to construct a top 100 at heavyweight. The workload of research and footage was no heavier, but I had overlooked the fact that the distinction between fighters ranked even twenty places apart would be tiny; in some cases almost meaningless.

Or at least, that was the case where the lower order was concerned. The top fifty was more cohesive. This was encouraging, and probably rescued my determination to construct thorough ATG lists for each of what is now typically known as “the eight original weight classes.” What you are now reading is the third such list, but the first one that is made up of only fifty fighters. Despite this I hope it loses considerably less than the fifty percent in worth one might imagine. Just as was the case with the heavies, right outside the top fifty things become extremely soft. There are around thirty fighters with a claim for spots #48 through #60 with very little to separate them and this makes their ordering rather meaningless. Within the fifty, the light-heavyweights come alive, suddenly vibrant and distinct. Ahead there are surprises but they are surprises formed by opinion based upon the facts that made up the careers these great fighters enjoyed and endured.

First among those surprises: no Bob Fitzsimmons, and no Jack O’Brien. In appraising light-heavyweights I haven’t gone any further back than 1903 and the point in history that is often seen as beginning of the division with Jack Root’s defeat of Charles McCoy. There were other dates that would have served almost as well, but this is the one I have selected.

Both Fitzsimmons and O’Brien held the title after this point, but both also did the bulk of their work before this point. If this seems a little unfair, consider that both were credited on the pound-for-pound list and on the heavyweight list for these earlier fights. Anything fought above middleweight in the earliest days of gloved boxing was considered a heavyweight fight, and this is how they were appraised by me.

Further to that, no fighter is credited more than once for any contest. For this reason, fights fought by men usually held to be light-heavyweights that were fought above the light-heavyweight limit will be considered to have engaged in a heavyweight contest and will not be credited here. As a rough guide, fighters matched at below 164lbs are generally held to have fought a middleweight contest and fighters matched at 180lbs and above are fighting at heavyweight. Also the weight class in question is always defined by the heavier fighter. If a 173lb man is fighting a 203lb man, he is engaging in a heavyweight contest. This list is interested almost exclusively in fights that took place within the light-heavyweight class.

As to what is considered for placings: opposition bested is the most pressing consideration. “Who did he beat?” is always the first question I ask, quickly followed by “how?” Ability on film, where it can be seen, plays a part, as do prime losses, dominance, and certain other intangibles that can make the difference between a lower spot and a higher one as they throw indistinct shapes from history into focus.

That’s the dull stuff out of the way – now let me introduce you the fifty greatest light-heavyweights of all time.

This, is how I have it:

#50 – Michael Moorer (52-4-1)

Michael Moorer rustled up just 22-0 at light-heayweight and he squeezed the usual quota of sharpening stones into his formative years. Heavyweight was where he made his reputation and his money, 175lbs was doubtless an aperitif and this is reflected in his ranking. In a sense, Moorer is the troubled soul of what has been a difficult project. From Freddie Mills (who falls outside the fifty) to Archie Moore (who, you will be unsurprised to hear, we won’t visit with until part five), a majority of these men spent the majority of their boxing lives rubbernecking the heavyweight division. As Moorer’s own career demonstrated, even the perpetual growth of the heavyweight division between Larry Holmes and Wladimir Klitschko hasn’t discouraged 175lb fighters adding thirty-fifty pounds and hurling themselves against the heavyweights.

My strict consideration of what a fighter achieves in the light-heavyweight division might, therefore, result in some interesting rankings, but Moorer’s place at #50 demonstrates that a part-time light-heavyweight can still receive his due. There are perhaps twenty other men that could have scooped this spot but what edged Moorer in through the closing door was not what he did but the way that he did it. Ramzi Hassan was his first visitation upon a ranked fighter and it was a brutal one. Moorer clubbed him out in five to claim a strap. Victor Claudio followed forty days later in two. Frank Swindell was coming off a first round stoppage of the once great Matthew Saad Muhammad when he took on Moorer forty days after that. Before the fight, Moorer spoke about being extended the full twelve by “tough guy” Swindell; the tough guy managed six rounds. He didn’t win any of them. By the time of his final light-heavyweight contest in December of 1990 he was boxing with the type of destructive surety that spoke of a possible reign of greatness.

It was not to be. A paucity of top class opposition in tandem with the eternal thirst of the light-heavyweight to become just a plain old heavyweight means he can rank no higher, but a 100% KO record and 22-0 squeezed into just 34 months means he cannot be ignored.

A final note – Moorer also ranked in my heavyweight top fifty…at #49. The temptation to rank him at #49 here was almost overwhelming.

#49 – Joe Knight (103-19-11)

But that slot is inhabited by the unheralded Joe Knight who will stand firm as the most underrated fighter on this list almost regardless of who else we come across on our travels; frankly only the hardcore among even a readership as well informed as that of the The Sweet Science will even have heard of him.

There are reasons for this. Despite being the beneficiary of alphabet-belt shenanigans that would make a 1980s heavyweight blush, Knight never lifted the legitimate, lineal light-heavyweight title, although he did get his shot, in February of 1934. The incumbent champion was the eccentric and brilliant Max Rosenbloom, as perplexing a riddle as can be seen in the opposite corner for a light-heavyweight title fight. But Knight had already solved Rosenbloom two years earlier, defeating him over ten rounds in 1932 and he was neither intimidated nor bamboozled. Rather he marched calmly in and fed the champion a steady diet of hooks to the body, giving him a sizeable lead going into the eleventh according to the great Tommy Loughran, who was in attendance. Rosenbloom, who had named Knight “the second best light-heavyweight in the country”, was a king, however, and an experienced one. He finished the stronger, dominating the final two frames to salvage a draw and his title.

This in turn illuminates the second reason for his lack of historical impact: a certain lack of aggression even with a hurt opponent on the hook in an important fight. He let the superb Tony Shucco clamber off the deck to rescue a draw in 1935 and his failure to put away a hurt opponent cost him a loss in a rematch the following year; a similarly wounded Patsy Perroni was able to draw level on the cards in 1936. But for all that, Knight’s decade was a healthy and impressive romp through a tough crew of fighters, losing a series with Bob Goodwin, winning one with Rosenbloom, outworking numerous other solid professionals to rank among the ten best in the world.

It’s true that he lost nineteen, but given that he only won five of his last ten and twelve of his first twenty, those one-hundred wins built for the most part during a superb prime run earns him the #49 spot I wanted to give to Moorer. It is fitting that a boxer who remained almost exclusively a light-heavyweight for his entire career should out-rank one who departed for heavyweight within three years.

#48 – Anton Christoforidis (54-15-8)

Anton Christoforidis runs Joe Knight close for the title of the most underrated fighter on this list. In 1943 he suffered back to back defeats against Jimmy Bivins, a fight he always held he won, and Lloyd Marshall, who he admitted had bested him. He then joined the US Navy, having taken up citizenship of the United States after leaving Turkey, his birthplace, Greece, his first adopted home and France, where he lived his salad days as a professional fighter, behind. When he returned to fighting, it was as a middleweight.

Similarly, he turned professional at middleweight, sparing him the losses then associated with an apprenticeship as well as those associated with a fistic dotage, leaving just his prime for the light-heavyweight division. And he did some superb work there.

He arrived on American soil in 1940, a move that coincided with his first real interest in the light-heavyweight division, announcing himself in that company in earnest with a double left-hook knockout of the prospect Jimmy Reeves. After dropping down to middleweight to go 1-1 with future nemesis Jimmy Bivins, a fight was arranged for the NBA’s light-heavyweight strap against the tough Melio Bettina, who very nearly made this list himself. Speed and stamina were the keynote attributes in a workmanlike and savvy performance that saw Christoforidis pound out a clean, come-from behind decision over the narrow favourite. His reign did not last long, in fact he lost his strap in his very first defence against Gus Lesnevich, but he continued to campaign in the division and cobbled together a fine resume of wins against some of the era’s better fighters, including close victories over Nate Brown and Johnny Colan.

It isn’t a stirring resume, but given light-heavyweight’s surprising lack of depth outside the top forty it’s enough to get him into the bottom ten of the top fifty.

#47 – Henry Maske (31-1)

There was a perception, I think, among the American fight fraternity in the 1990s that fighters who remained in Europe rather than set sail for the fight capital of the world were to be viewed with suspicion. Maske, though, won his critics on the other side of the Atlantic over despite having fought in USA just once, as a 7-0 prospect against a cruiserweight journeyman in a fight staged at a middling Hollywood hotel.

Returning home to his beloved Germany, never to leave Europe again for professional reasons, Maske earned respect with a thirty fight winning streak that eventually saw him named the best light-heavyweight on the planet by Ring magazine.

He likely first caught all but the sharpest of American eyes in March of 1993 by not just defeating but dominating the widely admired Ohioan, Charles Williams. It was a lesson in substance over style and in the deceptive appearance of Maske, who misled in all kinds of ways. There to be hit by eye, he actually had a superb judge of range, and the seemingly clear path to his jaw, a straight shot from wrist to chin, was actually littered with all kinds of sneaky, digging punches. Williams obliged Maske completely in driving himself on to these punches with an overly aggressive approach that the German ate up.

Lacking genuine fluidity on offence, Maske was an expert punch-picker even at 19-0 and was a prototype for Joe Calzaghe in the sense that he sacrificed in order to maintain punching opportunities. Where Calzaghe sacrificed balance, Maske sacrificed rhythm and certain gains his traditional technique may have brought him. It made Maske shifty, one big feint.

He deceived Iran Barkley when that old warhorse mad the trip, winning almost every round and jabbing the old man’s left eye shut with that southpaw jab, feeding him a steady diet of uppercuts when the American tried to rush, head down. Maske punished him sorely from that narrow-legged wide-armed stance in the ninth and Barkley refused to answer the bell for the tenth.

Perhaps a little lucky in taking an exquisitely close decision from Graciano Rocchigiani in May 1995, Maske provided his opponent with an immediate rematch and beat him clean, confirming his status as the best light-heavy on the planet. There are fighters who haven’t made this list who have might be favoured to beat Maske, guys like Eddie Cotton, guys like James Scott, but consistency, paper record and a delightful tendency to deceive opponent and spectator alike sees Maske sneak in ahead of them.

#46 – Willie Pastrano (62-13-8)

Willie Pastrano lifted the world’s light-heavyweight championship versus the brilliant Harold Johnson in the closest thing to a flat out robbery that the modern lineal kingship has ever seen. I scored no fewer than ten rounds for Harold Johnson and if this is extreme, it is still the case that most ringsiders (9-5 in a poll of sports reporters) saw the fight clearly for Johnson. It is hard to credit Pastrano for the win.

But he did fight a clever, foraging battle that night, and he did upset Johnson’s rhythm to a greater extent than geniuses such as Ezzard Charles so if he can’t be credited for the win he can perhaps be credited for a good effort. More, for all that he was handed the title, he did a fine job of defending it, stopping both Gregorio Peralta and Terry Downes.

Pastrano never inspired confidence in the public, his style too skittish to make believers of the fight-fans and Peralta started their title fight as a favourite, based upon his victory over Pastrano in a non-title fight; Pastrano blasted his eye wide open with a right hand while ahead on the cards, stopping him in five. Downes was also cut early but the Londoner proved more stubborn and was likely ahead at the beginning of the eleventh. Pastrano had travelled to Manchester for his second defence and found himself tucked up in a small ring against an aggressive hometown boy with the title on his mind – but he didn’t panic. Instead he boxed, moved when he could and when the time came to fight, he fought. The beginning of the eleventh was such a time, and supposedly inspired by a particularly blue tirade from an irate Angelo Dundee, Pastrano got up on his toes and boomed home two huge right hands; Downes never recovered and Pastrano proceeded to batter him about the ring until the referee was forced to intervene.

He lost his title in his very next defence, to Jose Torres, and promptly retired. Pre-title his career had been a mix of superb work against excellent heavyweight competition (including a 200lb Archie Moore and a 184lb Joey Maxim) and passable work against limited light-heavyweight competition, the probable highlights being his first contest with Chuck Spieser and his decision over Jerry Luedee. This is not top fifty form, but his good performances in title fights plus his gift decision over Harold Johnson gets this overachiever through the door head of light-heavyweight underachievers like James Toney and Bob Olin.

#45 – Mauro Mina (52-3-3)

When he was just 6-0 Peruvian Mauro Mina was defeated by future Brazilian national light-heavyweight champion Luis Ignacio. A year later, at 10-1-1, he lost to South-American light-heavyweight champion Dogomar Martinez over fifteen rounds. And that’s it. That’s all. Mina, who would never fight for the light-heavyweight championship, was never again defeated at the weight. His prime was an undefeated streak six years long interrupted only by a setback up at heavyweight.

Like all the great Central and South Americans (especially in this era), Mina’s first task was to place the massed banditry of his domestic scene under control. This was no small matter. Names like Huberto Loayza and Sixto Rodriguez may not call to mind famous faces, but they were serious men unaccustomed to letting local prospects escape their grasp without a fight. Mina beat out all comers, often in front of crowds of thousands, and eventually escaped to the United States where the veteran Henry Hank gave him a most unwelcome welcome. Already 11-0 versus American fighters paid to visit Peru, Mina included a victory over #1 contender Eddie Cotton on his ledger, but Hank pushed him hard in the early going. When the Peruvian got down off his toes however, he dominated, using his more traditional style to out-hit Hank with high pressure and some superb short-arm punching. A split decision win was his reward, to be followed by a shot at the light-heavyweight champion Harold Johnson.

Alas, it was not to be. Whether or not Mina would have tested Johnson with his crafty defence and his depth of style will never be known as an eye injury kept him from the championship ring. Hank, who met both men, certainly thought Mina’s chances were healthy claiming he was too strong for “anyone in the division.” The Peruvian continued to impress, climbing off the canvas to outpoint a green Bob Foster, defeating Cotton again and out-pointing the ranked Piero Del Papa in his very last fight, but when he retired there was a sense that his potential went unfulfilled.

#44 – Billy Miske (45-3-3; Newspaper Decisions 29-10-13)

Billy Miske is best known as the first victim of the title run of the heavyweight legend Jack Dempsey, but Miske boxed an entire career before he limped to the ring to face Jack and much of it was fought at the 175lb limit.

It is also true that Miske is known for making an attempt on the prime Dempsey’s title despite suffering the debilitating symptoms of Bright’s Disease, leading many to write him off as a valid opponent; less well known is that Miske had been battling these symptoms for years and suffered badly with them before many of his key battles at the weight. Before his summer 1919 confrontation with Tommy Gibbons he had, according to Clay Moyle, author of Billy Miske, nine boils lanced. In the week before the fight he was so weak with fever he could hardly rise form his bed. According to Miske himself, “my back ached, my legs were numb…I gritted my teeth and said “I’m going to go these ten rounds”…I don’t know how I did it.”

But he did do it, and in the opinion of the referee and several newspapermen in attendance he toughed it out to a draw, gameness and aggression his chief weapons against the brilliant Gibbons. The two fought a series across the span of seven years and it was one that was dominated by Gibbons, but in their only meeting at 175lbs, Miske held his own despite his desperate health. It is very possible that were he well, Miske might have found a shade in that fight.

The other key series in his career was fought against the great Jack Dillon, “The St.Paul Thunderbolt” and for all that Dillon had started to slip by the time Miske had started to dominate, when they first met in January of 1916 Dillon was at the tail end of his absolutely extraordinary prime. Heavily favoured, Dillon was shocked by Miske who, as he would throughout his career, refused to bow to any measure of punishment, remaining in the pocket with the much more experienced man and appearing to out-fight him there. Dillon claimed illness, and there may be something to this as he showed better in the rematch, taking his revenge, but it is a fact that by the end of their four fight series Miske was winning at a canter. He is generally credited with winning their rivalry three fights to one. He had developed a healthy habit of making Dillon miss with bodywork before hitting out with serious punches in return.

He could never get over on the deadly Kid Norfolk, or on the immortal Harry Greb but there is certainly no shame in that. Supporting wins over champion Battling Levinsky and the always willing Gunboat Smith see him enjoy an elevated ranking here – but certainly not one that he does not deserve.

#43 – Jeff Clarke (92-31-15; Newspaper Decisions 37-9-6)

Jeff Clarke was known as the Jopplin Ghost, The Fighting Ghost, a spectre of a boxer, gone from his flailing opponent in a step, offering the parting gift of an uppercut. So brilliant was Clarke that he was able, despite what was a definitive light-heavyweight’s frame, to straddle two divisions, making inroads into a hot heavyweight division. Clarke once defeated the brilliant heavyweight contender Joe Jeanette and dropped and out-boxed the fabled Sam Langford; yet his footprint on history is, perhaps fittingly, ghost-like.

Never a legitimate champion, he remorselessly pursued alphabet straps at the heavier weight, fighting for the Mexican heavyweight title, the Panamanian heavyweight title, the “coloured” heavyweight title. For an African-American fighter turning professional in the USA in 1908, there was really no other way to achieve financial security. His Herculean pursuit of heavyweight riches ironically hampers his ranking here. Had he fought in a later era he likely would have spent most of his career at the weight and found himself in the upper reaches of this list.

A counter-punching specialist, he was extremely hard to hit and more than capable of keeping from the era’s most dangerous punchers for distance fights, but when called to arms he was capable of duking it out with the best of them, as he proved against Kid Norfolk in May of 1915 in Panama City, stepping close to give one of the most brutal infighters of the era a solid lesson in the art.

Kid Norfolk would eventually catch up to him and as the older man Clarke was firmly dominated by Norfolk in the end. The Ghost spent almost ten years in a funk of losses and beatings as his career wound down, ruining his paper record but failing to obscure an excellence that continues to shine, barely, through the past century.

#42 – Jose Torres (41-3-1)

When people talk about “old-school” fighters they are talking about guys like Puerto Rican Jose Torres.

Check out his 1966 fight of the year with the timeless Eddie Cotton for a fine example. It’s not that Torres does anything we don’t see today but rather the way that he does it. There is no flashy shoulder-role or sizzling footwork, he just slips jabs with good reaction time, arbitrary head movement, technically sure positioning and well-drilled balance. The over-riding definition of old-school is economy – it is born of necessity as fighters trained and learned to box fifteen rounds, a whole 25% more than their modern counterparts. His moves at every range are dotted by a certain care that often cannot be seen in the modern ring. Nothing is wasted. His opponent, Cotton, is complicit in this and together they turn in one of the great light-heavyweight fights.

Torres delivered a similar performance against Willie Pastrano, from whom he took the title. Pastrano, probably, is past his best but this is Jose’s best effort on film, a fight in which he demonstrates all that is good about him. Moving forwards steadily in that now famous peekaboo style, gloves high, dipping and cutting the ring off on the fleet-footed Pastrano before the champion even knew where he was headed, a vicious body-attack the tip of his spear. It was a one-sided beating that resulted in the first stoppage of Pastrano’s career for any reason other than cuts. The reason on this occasion was an accumulation of punches that forced the referee’s hand between the ninth and tenth round.

In addition to his wonderful defeat of Cotton, Torres managed defences against former top contender Chic Calderwood, who he blasted out in two with a booming right to the ear, and the always game Wayne Thornton who he outclassed over fifteen.

Against this must be tempered Jose’s loss of the title to former middleweight Dick Tiger, a fighter totally incapable of filling out into a light-heavyweight, not once but twice. It is also true that he lifted the title against a fighter that probably should never have been in possession of it, Pastrano gifted a decision over Harold Johnson. Finally, Torres was not a career light-heavy, having fought many years at middleweight in the fruitless pursuit of a title shot.

Still, it is clear he belongs, even if the above is reason enough for me to see him a little lower than many Puerto Rican’s will care to see him.

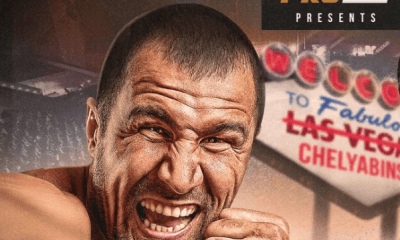

#41 – Sergey Kovalev (27-0-1)

It’s a strange thing with active fighters. I am writing just hours after Sergey Kovalev’s brutalisation of Jean Pascal in the latter’s hometown of Quebec, March the fifteenth, 2015. The fight was not close, but the fight was most entertaining and in the course of the fight Kovalev was checked for both chin and engine. He was the equal to both of these examinations, showed a wonderful patience in stalking his wounded opponent for the knockout, and devastated Pascal in eight surgical and brutal rounds. Had Kovalev lost that fight rather than inflicted upon Pascal his first ever stoppage defeat, he would now be ranked nowhere, and the great middleweight and sometime light-heavyweight Tiger Flowers would have crept into the #50 spot. As it is, Flowers languishes outside, and Kovalev assaults the dizzy, even absurd heights of #41, above one or two men whose names ring out as legendary.

Is it reasonable? Certainly it can be defended, although in a less traditional manner than the logic that supports much of this list. Firstly, Kovalev has now beaten more men ranked in the top five at light-heavyweight at the time that he met them than Anton Christoforidis (#46) and Mauro Mina (#45). He has defeated old-man Hopkins at a time when the great man was ranked the #1 light-heavyweight contender to the 175lb title. He is undefeated at the weight and has knocked out every ranked opponent he has ever faced aside from Hopkins.

I admit, still, there is a sneaking suspicion that perhaps Kovalev might be better suited to a spot a little further down, behind Clarke and Torres perhaps. What leads him to the #41 spot is this: if his ranking looks high now it will look low in a year’s time – that is because Kovalev is, by my reckoning, the best light-heavyweight since the heyday of one Roy Jones Junior. Experience has taught me it is better to be conservative in ranking active fighters, but this fighter seems a legitimate leviathan; so I have let my gut guide me.

Time, as always, will tell.

Follow Matt McGrain on Twitter: @McGrainM

Featured Articles

Sam Goodman and Eccentric Harry Garside Score Wins on a Wednesday Card in Sydney

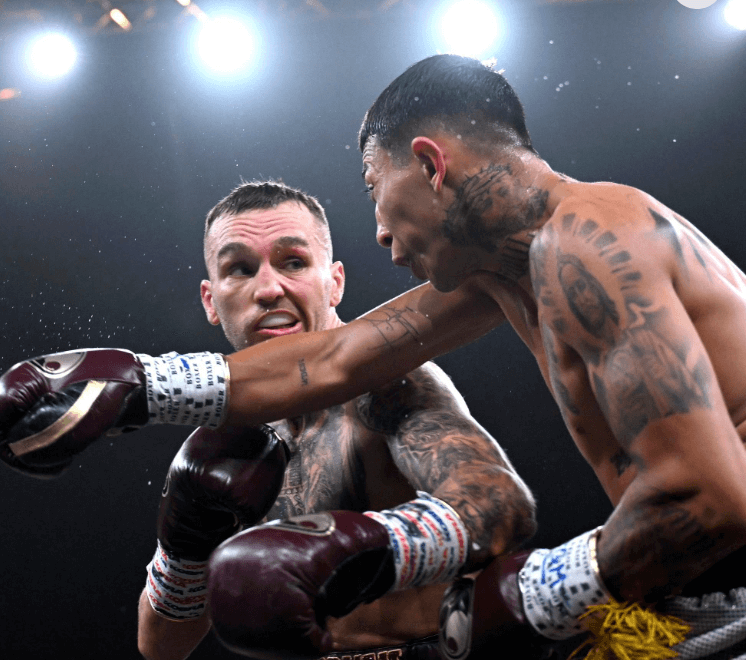

Australian junior featherweight Sam Goodman, ranked #1 by the IBF and #2 by the WBO, returned to the ring today in Sydney, NSW, and advanced his record to 20-0 (8) with a unanimous 10-round decision over Mexican import Cesar Vaca (19-2). This was Goodman’s first fight since July of last year. In the interim, he twice lost out on lucrative dates with Japanese superstar Naoya Inoue. Both fell out because of cuts that Goodman suffered in sparring.

Goodman was cut again today and in two places – below his left eye in the eighth and above his right eye in the ninth, the latter the result of an accidental head butt – but by then he had the bout firmly in control, albeit the match wasn’t quite as one-sided as the scores (100-90, 99-91, 99-92) suggested. Vaca, from Guadalajara, was making his first start outside his native country.

Goodman, whose signature win was a split decision over the previously undefeated American fighter Ra’eese Aleem, is handled by the Rose brothers — George, Trent, and Matt — who also handle the Tszyu brothers, Tim and Nikita, and two-time Olympian (and 2021 bronze medalist) Harry Garside who appeared in the semi-wind-up.

Harry Garside

Harry Garside

A junior welterweight from a suburb of Melbourne, Garside, 27, is an interesting character. A plumber by trade who has studied ballet, he occasionally shows up at formal gatherings wearing a dress.

Garside improved to 4-0 (3 KOs) as a pro when the referee stopped his contest with countryman Charlie Bell after five frames, deciding that Bell had taken enough punishment. It was a controversial call although Garside — who fought the last four rounds with a cut over his left eye from a clash of heads in the opening frame – was comfortably ahead on the cards.

Heavyweights

In a slobberknocker being hailed as a shoo-in for the Australian domestic Fight of the Year, 34-year-old bruisers Stevan Ivic and Toese Vousiutu took turns battering each other for 10 brutal rounds. It was a miracle that both were still standing at the final bell. A Brisbane firefighter recognized as the heavyweight champion of Australia, Ivic (7-0-1, 2 KOs) prevailed on scores of 96-94 and 96-93 twice. Melbourne’s Vousiuto falls to 8-2.

Tim Tsyzu.

The oddsmakers have installed Tim Tszyu a small favorite (minus-135ish) to avenge his loss to Sebastian Fundora when they tangle on Sunday, July 20, at the MGM Grand in Las Vegas.

Their first meeting took place in this same ring on March 30 of last year. Fundora, subbing for Keith Thurman, saddled Tszyu with his first defeat, taking away the Aussie’s WBO 154-pound world title while adding the vacant WBC belt to his dossier. The verdict was split but fair. Tszyu fought the last 11 rounds with a deep cut on his hairline that bled profusely, the result of an errant elbow.

Since that encounter, Tszyu was demolished in three rounds by Bakhram Murtazaliev in Orlando and rebounded with a fourth-round stoppage of Joey Spencer in Newcastle, NSW. Fundora has been to post one time, successfully defending his belts with a dominant fourth-round stoppage of Chordale Booker.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

Featured Articles

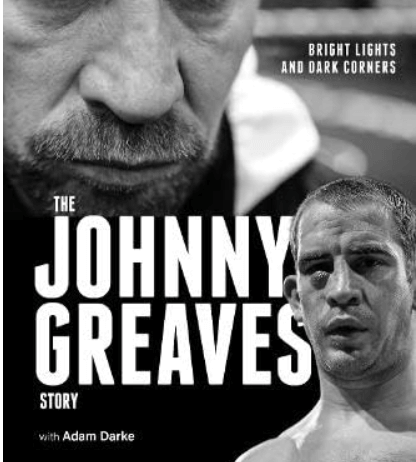

Thomas Hauser’s Literary Notes: Johnny Greaves Tells a Sad Tale

Johnny Greaves was a professional loser. He had one hundred professional fights between 2007 and 2013, lost 96 of them, scored one knockout, and was stopped short of the distance twelve times. There was no subtlety in how his role was explained to him: “Look, Johnny; professional boxing works two ways. You’re either a ticket-seller and make money for the promoter, in which case you get to win fights. If you don’t sell tickets but can look after yourself a bit, you become an opponent and you fight to lose.”

By losing, he could make upwards of one thousand pounds for a night‘s work.

Greaves grew up with an alcoholic father who beat his children and wife. Johnny learned how to survive the beatings, which is what his career as a fighter would become. He was a scared, angry, often violent child who was expelled from school and found solace in alcohol and drugs.

The fighters Greaves lost to in the pros ran the gamut from inept local favorites to future champions Liam Walsh, Anthony Crolla, Lee Selby, Gavin Rees, and Jack Catterall. Alcohol and drugs remained constants in his life. He fought after drinking, smoking weed, and snorting cocaine on the night before – and sometimes on the day of – a fight. On multiple occasions, he came close to committing suicide. His goal in boxing ultimately became to have one hundred professional fights.

On rare occasions, two professional losers – “journeymen,” they’re called in The UK – are matched against each other. That was how Greaves got three of the four wins on his ledger. On September 29, 2013, he fought the one hundredth and final fight of his career against Dan Carr in London’s famed York Hall. Carr had a 2-42-2 ring record and would finish his career with three wins in ninety outings. Greaves-Carr was a fight that Johnny could win. He emerged triumphant on a four-round decision.

The Johnny Greaves Story, told by Greaves with the help of Adam Darke (Pitch Publishing) tells the whole sordid tale. Some of Greaves’s thoughts follow:

* “We all knew why we were there, and it wasn’t to win. The home fighters were the guys who had sold all the tickets and were deemed to have some talent. We were the scum. We knew our role. Give some young prospect a bit of a workout, keep out of the way of any big shots, lose on points but take home a wedge of cash, and fight again next week.”

* “If you fought too hard and won, then you wouldn’t get booked for any more shows. If you swung for the trees and got cut or knocked out, then you couldn’t fight for another 28 days. So what were you supposed to do? The answer was to LOOK like you were trying to win but be clever in the process. Slip and move, feint, throw little shots that were rangefinders, hold on, waste time. There was an art to this game, and I was quickly learning what a cynical business it was.”

* “The unknown for the journeyman was always how good your opponent might be. He could be a future world champion. Or he might be some hyped-up nightclub bouncer with a big following who was making lots of money for the promoter.”

* “No matter how well I fought, I wasn’t going to be getting any decisions. These fights weren’t scored fairly. The referees and judges understood who the paymasters were and they played the game. What was the point of having a go and being the best version of you if nobody was going to recognize or reward it?”

* “When I first stepped into the professional arena, I believed I was tough. believed that nobody could stop me. But fight by fight, those ideas were being challenged and broken down. Once you know that you can be hurt, dropped and knocked out, you’re never quite the same fighter.”

* “I had started off with a dream, an idea of what boxing was and what it would do for me. It was going to be a place where I could prove my toughness. A place that I could escape to and be someone else for a while. For a while, boxing was that place. But it wore me down to the point that I stopped caring. I’d grown sick and tired of it all. I wished that I could feel pride at what I’d achieved. But most of the time, I just felt like a loser.”

* “The fights were getting much more difficult, the damage to my body and my psyche taking longer and longer to repair after each defeat. I was putting myself in more and more danger with each passing fight. I was getting hurt more often and stopped more regularly. Even with the 28-day [suspensions], I didn’t have time to heal. I was staggering from one fight to the next and picking up more injuries along the way.”

* “I was losing my toughness and resilience. When that’s all you’ve ever had, it’s a hard thing to accept. Drink and drugs had always been present in my life. But now they became a regular part of my pre-fight preparation. It helped to shut out the fear and quieted the thoughts and worries that I shouldn’t be doing this anymore.”

* “My body was broken. My hands were constantly sore with blisters and cuts. I had early arthritis in my hip and my teeth were a mess. I looked an absolute state and inside I felt worse. But I couldn’t stop fighting yet. Not before the 100.”

* “I had abused myself time after time and stood in front of better men, taking a beating when I could have been sensible and covered up. At the start, I was rarely dropped or stopped. Now it was becoming a regular part of the game. Most of the guys I was facing were a lot better than me. This was mainly about survival.”

* “Was my brain f***ed from taking too many punches? I knew it was, to be honest. I could feel my speech changing and memory going. I was mentally unwell and shouldn’t have been fighting but the promoters didn’t care. Johnny Greaves was still a good booking. Maybe an even better one now that he might get knocked out.”

* “Nobody gave a f*** about me and whether I lived or died. I didn’t care about that much either. But the thought of being humiliated, knocked out in front of all those people; that was worse than the thought of dying. The idea of being exposed for what I was – a nobody.”

* “I was a miserable bastard in real life. A depressive downbeat mouthy little f***er. Everything I’ve done has been to mask the feeling that I’m worthless. That I have no value. The drinks and the drugs just helped me to forget that for a while. I still frighten myself a lot. My thoughts scare me. Do I really want to be here for the next thirty or forty years? I don’t know. If suicide wasn’t so impactful on people around you, I would have taken that leap. I don’t enjoy life and never have.”

So . . . Any questions?

****

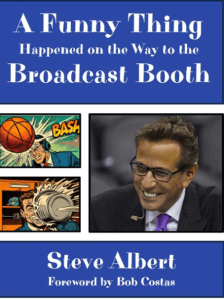

Steve Albert was Showtime’s blow-by-blow commentator for two decades. But his reach extended far beyond boxing.

Albert’s sojourn through professional sports began in high school when he was a ball boy for the New York Knicks. Over the years, he was behind the microphone for more than a dozen teams in eleven leagues including four NBA franchises.

Putting the length of that trajectory in perspective . . . As a ballboy, Steve handed bottles of water and towels to a Knicks back-up forward named Phil Jackson. Later, they worked together as commentators for the New Jersey Nets. Then Steve provided the soundtrack for some of Jackson’s triumphs when he won eleven NBA championships as head coach of the Chicago Bulls and Los Angeles Lakers.

It’s also a matter of record that Steve’s oldest brother, Marv, was arguably the greatest play-by-play announcer in NBA history. And brother Al enjoyed a successful career behind the microphone after playing professional hockey.

Now Steve has written a memoir titled A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Broadcast Booth. Those who know him know that Steve doesn’t like to say bad things about people. And he doesn’t here. Nor does he delve into the inner workings of sports media or the sports dream machine. The book is largely a collection of lighthearted personal recollections, although there are times when the gravity of boxing forces reflection.

“Fighters were unlike any other professional athletes I had ever encountered,” Albert writes. “Many were products of incomprehensible backgrounds, fiercely tough neighborhoods, ghettos and, in some cases, jungles. Some got into the sport because they were bullied as children. For others, boxing was a means of survival. In many cases, it was an escape from a way of life that most people couldn’t even fathom.”

At one point, Steve recounts a ringside ritual that he followed when he was behind the microphone for Showtime Boxing: “I would precisely line up my trio of beverages – coffee, water, soda – on the far edge of the table closest to the ring apron. Perhaps the best advice I ever received from Ferdie [broadcast partner Ferdie Pacheco] was early on in my blow-by-blow career – ‘Always cover your coffee at ringside with an index card unless you like your coffee with cream, sugar, and blood.’”

Writing about the prelude to the infamous Holyfield-Tyson “bite fight,” Albert recalls, “I remember thinking that Tyson was going to do something unusual that night. I had this sinking feeling in my gut that he was going to pull something exceedingly out of the ordinary. His grousing about Holyfield’s head butts in the first fight added to my concern. [But] nobody could have foreseen what actually happened. Had I opened that broadcast with, ‘Folks, tonight I predict that Mike Tyson will bite off a chunk of Evander Holyfield’s ear,’ some fellas in white coats might have approached me and said, ‘Uh, Steve, could you come with us.'”

And then there’s my favorite line in the book: “I once asked a fighter if he was happily married,” Albert recounts. “He said, ‘Yes, but my wife’s not.'”

“All I ever wanted was to be a sportscaster,” Albert says in closing. “I didn’t always get it right, but I tried to do my job with honesty and integrity. For forty-five years, calling games was my life. I think it all worked out.”

Thomas Hauser’s email address is thomashauserwriter@gmail.com. His next book – The Most Honest Sport: Two More Years Inside Boxing – will be published this month and is available for preorder at:

https://www.amazon.com/Most-Honest-Sport-Inside-Boxing/dp/1955836329

In 2019, Hauser was selected for boxing’s highest honor – induction into the International Boxing Hall of Fame.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

Featured Articles

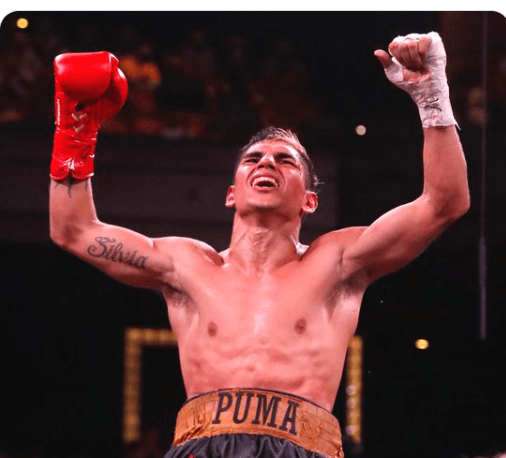

Argentina’s Fernando Martinez Wins His Rematch with Kazuto Ioka

In an excellent fight climaxed by a furious 12th round, Argentina’s Fernando Daniel Martinez came off the deck to win his rematch with Kazuto Ioka and retain his piece of the world 115-pound title. The match was staged at Ioka’s familiar stomping grounds, the Ota-City General Gymnasium in Tokyo.

In their first meeting on July 7 of last year in Tokyo, Martinez was returned the winner on scores of 117-111, 116-112, and a bizarre 120-108. The rematch was slated for late December, but Martinez took ill a few hours before the weigh-in and the bout was postponed.

The 33-year-old Martinez, who came in sporting a 17-0 (9) record, was a 7-2 favorite to win the sequel, but there were plenty of reasons to favor Ioka, 36, aside from his home field advantage. The first Japanese male fighter to win world titles in four weight classes, Ioka was 3-0 in rematches and his long-time trainer Ismael Salas was on a nice roll. Salas was 2-0 last weekend in Times Square, having handled upset-maker Rolly Romero and Reito Tsutsumi who was making his pro debut.

But the fourth time was not a charm for Ioka (31-4-1) who seemingly pulled the fight out of the fire in round 10 when he pitched the Argentine to the canvas with a pair of left hooks, but then wasn’t able to capitalize on the momentum swing.

Martinez set a fast pace and had Ioka fighting off his back foot for much of the fight. Beginning in round seven, Martinez looked fatigued, but the Argentine was conserving his energy for the championship rounds. In the end, he won the bout on all three cards: 114-113, 116-112, 117-110.

Up next for Fernando Martinez may be a date with fellow unbeaten Jesse “Bam” Rodriguez, the lineal champion at 115. San Antonio’s Rodriguez is a huge favorite to keep his title when he defends against South Africa’s obscure Phumelela Cafu on July 19 in Frisco, Texas.

As for Ioka, had he won today’s rematch, that may have gotten him over the hump in so far as making it into the International Boxing Hall of Fame. True, winning titles in four weight classes is no great shakes when the bookends are only 10 pounds apart, but Ioka is still a worthy candidate.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoMekhrubon Sanginov, whose Heroism Nearly Proved Fatal, Returns on Saturday

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 322: Super Welterweight Week in SoCal

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoTSS Salutes Thomas Hauser and his Bernie Award Cohorts

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoGabriela Fundora KOs Marilyn Badillo and Perez Upsets Conwell in Oceanside

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks ago‘Krusher’ Kovalev Exits on a Winning Note: TKOs Artur Mann in his ‘Farewell Fight’

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoFloyd Mayweather has Another Phenom and his name is Curmel Moton

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

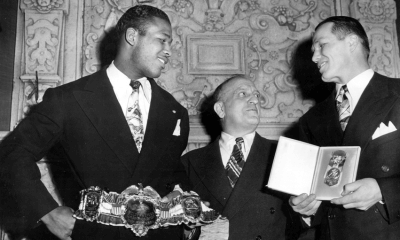

Featured Articles4 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: The First Boxing Writers Assoc. of America Dinner Was Quite the Shindig

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 323: Benn vs Eubank Family Feud and More