Featured Articles

The Fifty Greatest Middleweights of All Time Part Two: 40-31

In the introduction to Part One I alluded to the astonishing depth of the middleweight division; that depth is illustrated by the array of talent in Part Two. It is not unusual to stumble across a fighter ranked in the thirties on a list like this that can meet with the very best that lie above on their own terms, but we meet now a swathe of them – head-to-head monsters that were swallowed up by the leviathan of modern weight categorisation abound, but are not alone. Sacred cows, too, are slaughtered on the rocks of superior resume – at least three of the men ranked herein can be seen in top tens elsewhere.

And the frightening thing is that the middleweights are only going to get greater.

#40 MIKE MCCALLUM (49-5-1)

Among the greatest light-middleweights of all time, Mike McCallum’s career up at middleweight remains a nearly – nearly lineal middleweight champion of the world, nearly the conqueror of James Toney. In the end, a draw and a majority loss in two fights that could have been scored any one of three ways was the final result of his pair with Toney at 160lbs and it dooms McCallum to the #40 spot where a single point on a single card of the drawn first fight between the two would have propelled him up the list; such are the tiny screws upon which boxing greatness are turned.

Still, McCallum probably overachieved given the limited amount of time he spent in the division. He boxed as few as seven times at 160lbs and won just four of those contests. Outside of those two razor thin failures against Toney, McCallum also went 1-1 with Sumbu Kalambay, making him 1-2-1 with men on this list, but what men. James Toney, a simmering poisonous stew of hostility and near-genius can be read about later in this installment; for details concerning his disastrous loss to Kalambay in their first fight see Part One – as to his vengeance, earned in a split decision three years later, it was a desperately close fight that illustrated McCallum’s exquisite ability for identifying and boxing to an opponent’s killzone while underlining his limitations at the weight. He just didn’t have the physicality to bully Kalambay out of there in the first half of the fight and Kalambay insidiously boxed his way back in and the contest became another desperately close one that could have gone either way.

Still, when allowed to dominate as he was against another superb technician, Michael Watson, he was lethal, remorseless in his heavy-bagging of the world-class Watson who McCallum broke in eleven. He couldn’t break a spirited and green Steve Collins though and he was run extremely close by a riffing, winging Herol Graham – and that, really, is the story of McCallum at middleweight. It is not enough to see him given a higher slot but the teak-tough, keen-eyed Bodysnatcher belongs.

#39 – GEORGIE ABRAMS (48-10-3)

Compact and aggressive, Georgie Abrams was credited by Sugar Ray Robinson of giving him one of the hardest fights of his career. “He knows how to make you throw a punch and miss it” Sugar complained as though he hadn’t met some of the most astonishing talent ever to take to a boxing ring. Never a champion, he clashed with an incredible line-up of former and future champions belonging to the 1930s and 1940s all while wearing the demeanour and physicality of a failed ice-cream vendor.

First up was a creaking Teddy Yarosz, who a relatively green Abrams out punched over ten rounds to a split decision while neutralising Teddy’s lethal left. Next was strap holder Lou Brouillard, followed quickly by future belt-holder Billy Soose, who went for a second time in 1940 after being dropped in the first by a sizzling right-hand. The conciseness of his work always surprises, perhaps due to the absurd raggedness of his personal appearance.

After the second Soose triumph, Abrams took a break from championship opposition but continued to take on royalty, matching the peerless Charley Burley – and holding him to a draw, a rally in the ninth and tenth rescuing him from a defeat that at one point seemed sure. Another desperately close fight followed against another uncrowned champion in Cocoa Kid, the difference between the two narrow enough to serve as a draw but Abrams took the split of the decision. He then defeated Soose once more in a one-sided contest that surely entitled him to a shot at Soose’s belt; in a story as old as boxing, Soose declined.

Abrams tended to lose to the best he faced – Marcel Cerdan, Ray Robinson and Tony Zale all got over on him in important fights – but he did enough damage against enough outstanding fighters that a spot in the top forty is justified.

#38 – MARCEL CERDAN (111-4)

It is impossible to persistently undermine popular thinking in writing without exercising critical thinking, but equally it is hard to persistently undermine accepted thinking without overworking in defence of the new idea. The new idea here is that Marcel Cerdan, while superb and to be ranked among the greatest middleweights in history, is not among the very greatest as is held by Boxing Scene (12), the IBRO (7) and Herb Goldman (5) among many others. I have him dragging his heels here in the thirties. Why?

First of all, Cerdan’s extraordinary paper record is a little deceptive when it comes to ranking him as a middleweight; when he first fought in a meaningful middleweight contest, he was already 88-2, having established himself in the war years first and foremost as a welterweight. The end of the war was a signal for the 5’8 Cerdan to step up to the 160lb division where he was indeed dominant over European competition in his native France before boarding a steamship to the United States. The competition that Cerdan bested in this time was not bad, but nor did any of the middleweights he bested emerge as top contenders or champions or make any mark upon middleweight history in their own right. It was not until he made it to America that Cerdan marked himself truly special – allowing that he had already established his excellence, professionalism and consistency – with a victory over the wonderful Holman Williams. Williams, a veteran of one-hundred and seventy contests, was clearly beginning to slip and had recently been beaten by Bert Lytell; of the sixteen fights that remained Williams, he would win just five.

Nevertheless, he was a significant scalp for a visiting fighter, as was that of Georgie Abrams.

Abrams was also past his prime and had only one more career win ahead of him but was still dangerous and Cerdan hit the trenches in order that he might best him. Both fighters emerged cut from a bruising encounter that seems to narrowly but clearly belonged to Cerdan; after which he set sail for Europe to pick up the European title from a fighter called Leon Fouquet, who is listed by Boxrec as 2-4-1 going in. After returning to America and hammering the solid Jean Walzack and then going back to Europe to go 1-1 with Cyrille Delannoit, Cerdan got his title shot at Tony Zale.

It would be Zale’s last ever fight and Cerdan was extraordinary in taking the title, his left hook in particular, a thing of beauty and a punch he would use to force “The Man of Steel” to the canvas win the eleventh round. Zale did not emerge from the twelfth.

Cerdan was the lineal middleweight champion but he completed no successful defences, injuring his shoulder swinging for Jake LaMotta in their celebrated contest and then killed in a plane crash before their re-match. This is tragic but it restricted the number of years Cerdan fought in the division to five; this is the same as the number of ranked opponents he defeated. Two losses in that time is a fantastic return but ranked just above Cerdan is Randy Turpin. Turpin, like Cerdan, staged but a single defence of the title but whereas Cerdan beat a faded Zale, Turpin beat one Sugar Ray Robinson; their relative placement is arguable, yes, but that is because it is close. Above him is Michael Nunn. Nunn staged four defences of the lineal title to Cerdan’s one (plus additional defences of his strap) and defeated just as many ranked fighters; I also think he looks better than Cerdan on film at his best, and should be favoured could the two ever meet. The latter is debatable; the former is not. Why then, would Cerdan be ranked above Nunn? What reason exists? Because he built a better paper record at welterweight? I submit that Cerdan, though special, did nothing to distinguish himself from Nunn and nothing to distinguish himself from the fighters ranked above Nunn. Clearly excellent, he no more belongs in the top twenty at the weight than any of these men and any argument to include him there is by definition unsubstantiated.

#37 – RANDY TURPIN (66-8-1)

There is a statue of Randy Turpin in his hometown. They love him there. That he died the darkest of deaths does not matter to the population of Warwick, England. He rose to do the impossible. He rose to defeat the great Sugar Ray Robinson.

Robinson took to the road after his defeat of Jake LaMotta for the world’s middleweight champion in early 1951 and defeated European contenders in Italy, Germany, Belgium, Switzerland and France accruing cash and glory as he travelled. In London, Turpin lay wait, and plotted.

He was an old-fashioned fighter. He stabbed with his jab, the old fencing jab that birthed the punch, springing in with his arm held stiff like a foil, but he was fast and accurate. On defence, he leaned back, even reared up in the face of assault, trying to ride punches while defending with his shoulders, his hands low, turning and turning with whatever fuselage came his way. But he embraced, also, modern tools in his mission to overcome the invincible Robinson, whose record stood at 128-1-2. Already an obsessional trainer who had worked on his physical strength both in the gym and in a job obtained specifically to strengthen him further as a builder’s labourer, Turpin now sat patiently as films of Robinson boxing were run for him over and over again in order that he might first absorb the man he had sworn to defeat. It worked. Robinson’s two-fisted attack to the body, deployed against stronger opponents while going away from them in clinches was euthanized simply by drawing Robinson close and cracking him to the back and side of the head with whipped in punches bereft of arrowhead but loaded with scree. Robinson’s sneak right hand to the body around the corner just before or just after clinches were smothered by his bobbing out of a squat and into straight-backed conformity just before or just after a clinch was made. To dominate at range, he employed a technique as old to him as combat itself.

“He didn’t need a lot of teaching,” said Ron Stefani, his first fistic trainer some years after Turpin’s death. “It just seemed to come naturally to him…he didn’t have to manoeuvre round for openings, and as soon as they were there, bang!”

Turpin banged Robinson repeatedly, and it was not long before one of the greatest fighters of them all looked nothing short of lost in the ring. It was not a close fight; Turpin dominated him inside and out.

Famously, he held the title for just sixty-four days before Robinson ripped it from him once more by explosive stoppage; Turpin never again approached the astonishing peak he reached that night in London against Robinson. Indeed, his wider resume is only respectable – ranked contenders like George Angelo and Charles Humez brutalised like Robinson was brutalised if not quite so spectacularly – but the other top men he met like Bobo Olson and Tiberio Mitri brushed him aside.

But what price a domination of Sugar Ray Robinson in 1951? High enough that he is guaranteed a spot on this list.

#36 – MICHAEL NUNN (58-4)

Michael Nunn was huge, fast, powerful and a southpaw, an absolutely terrifying mix of attributes that made him one of the most feared fighters on the planet in the late 1980s.

Nursed a little through his early years as a professional, decent wins over unranked fighters like Darnell Knox and Willie Harris seemed perhaps to have left him unprepared for his first ranked opponent, strap holder Frank Tate, a fighter who held two victories over Nunn in the amateurs and who was 23-0 as a professional. Watching the fight now, one can see what it was that Tate set out to do, namely nail down a flashy, elusive opponent with textbook boxing and patient pressure, but he was completely outclassed. Nunn had such speed and accuracy that he could find punches that Tate was not equipped to deal with, reaching all the way across himself with a trailing left to land a power-punch below Tate’s right elbow after blasting him with a more traditional southpaw jab. Meanwhile Tate’s own punches, for the most part, were lost to the wind as Nunn ditched them with a reaction’s based defence that left Tate clawing at the air. The left-hand Nunn used to fold Tate to the canvas at the end of the eighth looked almost incidental to the general sea of leather Nunn crashed down on Tate’s shore but it heralded the end in round nine among a tsunami of hooks that forced referee Mills Lane to intervene.

Nunn had taken his amateur style and fused it to the cornerstones of a professional fighter, throwing with bad intentions and boxing with a heart-fuelled determination to dominate his opponent. It was a heady combination and his victory over Tate heralded four years of fearsome middleweight tyranny that included a three year reign as the lineal middleweight champion. This most important of titles was sealed after his brutal retirement of the old warhorse Juan Domingo Roldan with the most astonishing knockout of 1989, his first round dispatch of Sumbu Kalambay.

Kalambay was supposed to be a step up for Nunn, a class apart from what had gone before. Nunn destroyed him with a single punch, and more impressive, a single punch of exactly the type that Kalambay excelled in throwing, a straight thrown against an opponent who had been manoeuvred directly across him. Kalambay victim Iran Barkley was up next, and he provided his usual level of stubborn resistance, even taking a draw on one of the official scorecards (and mine), Nunn winning by a narrow margin from an aggressive opponent. Uncertainty regarding Nunn’s fighting qualities, rampant before his destruction of Kalambay, re-emerged. These were deepened still further by a desperately close majority decision win over Marlon Starling, the wonderful welterweight champion. Nunn, bigger than most of his middleweight opposition, held an almost comical size advantage over Starling but the welterweight king repeatedly found his larger opponent with lead right-hands. Nunn reclaimed some ground overwhelming another former welterweight champion, Don Curry, in ten, but then a menacing and full-sized middleweight stepped out of the shadow and knocked him catastrophically out; with that the reign of James Toney began.

The end of Nunn’s reign signalled eternal speculation as to his great potential and why he didn’t fulfil it. The reason he didn’t fulfil it is simple: it wasn’t there. Nunn was no better and no worse than his record indicates. Just as the harsh realities of boxing dictate that it is Nunn who holds Sumbu Kalambay’s reigns in terms of his historical standing, so it is that Toney holds Nunn’s.

#35 ROY JONES JNR. (61-8)

I can only imagine the horror with which acolytes of Roy Jones greet his “lowly” position upon the list, and below so many men who never boxed in colour. For the sake of the Jonesites of this world (assuming any are still reading), a quick reminder of the criteria, described with more completeness in Part One.

Firstly, nothing that Jones accomplished outside the confines of middleweight plus a few pounds is considered here; his inherent superiority over James Toney was proven, yes, but that was in a fight that occurred in a different weight division, and in the meantime it must be considered that Toney achieved more at middleweight, as shall be seen. Achievements, who a fighter beat, how long he held the title should he have come to it, and how dominant he was over his era stand in excess of how good a fighter looks on film.

That said, prowess in the ring cannot be ignored, nor can skillsets, athletic excellence or the probable outcome of imagined meetings with the rest of the field. This is just as well for Roy and his many fans because, to be absolutely frank, Roy doesn’t belong on this list based upon what he did at middleweight. The reason he’s ranked here is specifically because he was so special.

Jones turned professional in 1989 at 160lbs and did not part with the division until 1994, by which time he had amassed a record of 25-0. Included in that record were three fights fought at super-middleweight leaving us twenty-three middleweight contests. Roy’s fifteenth fight was fought against a boxer named Lester Yardbrough, who carried with him to the ring a record of 12-16-1. It is fair to say that Jones was very heavily protected in the early part of his career – there was even speculation that his father and manager, who ruled Roy with an iron fist at that time, refused to extend his fighter and son the challenges he so clearly required.

In his sixteenth fight though, Roy met with the washed up, undersized Jorge Vaca, hardly world-beating opposition but a valid opponent for a young fighter. Jones disposed of him in a round. A few months later he met the hugely experienced Jorge Fernando Castro, unranked at middleweight but previously ranked at light-middle, and for the first time was extended the distance. Showing either good judgement or a surprising level of paranoia depending upon your point of view, his sense that Castro was trying to “lure him in” probably cost him the stoppage. He did stop his next three opponents in a total of thirteen rounds but still, none of them were ranked. His second to last opponent at the weight though, was ranked: one Bernard Hopkins.

But he was ranked in the bottom half of the middleweight top ten. Hopkins was a long way from prime, his style’s perfection reliant upon pacing, strategy, distance and angles, all learned attributes that Hopkins, who had never defeated a ranked contender and was still a year from being dropped twice on his way to a draw with Segundo Mercado, had yet to master. If Roy’s impressive, one-sided domination of Hopkins is the hook his legacy hangs on, he is grossly overrated at #35, not underrated.

Thankfully, it does not. There is room here for good legacy, which Jones has, married to exceptional talent. A justifiable argument could be made for ranking Michael Nunn ahead of him, but what of the feeling that he would probably bamboozle Nunn while playing him delightedly at his own game? Roy moved up to super-middleweight after Hopkins, but he came back down for a single defence of the strap he picked up against the man who would become The Executioner, and took out the ranked Thomas Tate in short order. Jones looked, in that fight, like he came from another planet. If he has a “middleweight prime” it lasted those two rounds Tate spent with him 1994. It’s special enough to see him ranked alongside fighters who defeated legitimate all-time great fighters in or around their primes. Those who consider him underrated would do well to remember this.

#34 – BILLY CONN (64-11-1)

History’s eye alights only momentarily upon fighters like Georgie Abrams but Billy Conn is among the most recognised fighters in boxing, a smiling Irishman who reigned as the world’s light-heavyweight champion and who came within minutes of taking the world’s heavyweight title from Joe Louis before instead suffering the most glorious defeat in the history of the sport. Still, I suspect that while Abram’s placement in the top forty at middleweight will breeze by unnoticed, Conn’s will raise a few eyebrows; it should not. Conn achieved great things long before he set foot in the light-heavyweight division.

He turned professional as a scrawny teenage lightweight but soon filled out into the middleweight division where he served a demanding apprenticeship across five fights with the absurdly tough Honey Boy Jones before dominating a creaking Ralph Chong and squeaking by the legendary, but physically overmatched, Fritzie Zivic. Zivic represented something of a graduation night for Conn and it is no coincidence that in the wake of that points victory he began his run against champions and greats of the middleweight division. Babe Risko, a strap holder just one year before, went first, but was outclassed by the young Conn over ten. Centurion Vince Dundee went next. On the comeback trail it was some three years since Dundee had held a belt, but Conn named this his hardest fight to that date. Nevertheless, he won it with points to spare and drew the admiration of both Dundee and the Pennsylvania crowd.

Things got harder for Conn in his very next fight as he met with ranked tough Oscar Rankins, who was coming off a win over the excellent Solly Krieger. He came very close to adding Billy to the resume when in the second round he caught him with a steaming right hand high on the jaw. Conn delivered himself to the canvas face-first and looked to all intents and purposes beaten. Up at nine, he was driven around the ring by a merciless Rankins body-attack; but he did not succumb. Depending upon which press reports you prefer, Conn came driving back with a matchless gameness to smuggle out a deserved split decision, or Rankins was jobbed after winning the necessary six out of ten rounds. My own guess is that this was a desperately close fight that could have gone either way but unsurprisingly went to the teenage Irish prospect over the solid African-American contender.

Conn forged ahead fighting two pairs with the much more experienced Teddy Yarosz and, as detailed elsewhere in this series, Young Corbett. Yarosz dominated Conn early in their first fight, but Conn, exalting audibly in his own conditioning between rounds, forced his way back into the contest with a left-hook in the fourth and a right-hand in the fifth, both of which troubled Yarosz; after six, the fight seemed even and as to what occurred next, each judge, newspaperman and fan present seemed to tell a different story. The outcome was once again a desperately narrow split in Conn’s favour. A rematch was a necessity but solved nothing; sportswriter Regis Welsh under the headline “It’s An Argument: Second Conn-Yarosz Just As Debatable As The First” suggested that Yarosz needed to gather more stamina in support of his style to prevent the disastrous fade he suffered in the second fight and that Conn, breaks or not, was forcing upon him, but also hinted that the decision was “off-colour”. Without the mitigation of film, it is not for me to overturn an official decision, but it can be said perhaps that Conn did not prove his definitive superiority to Yarosz – while accepting that Yarosz certainly did not prove his superiority to Conn.

Yarosz, the reader can rest assured, features nearer the summit than Conn. This is due simply to the fact that he spent many more years boxing in the weight-class while Conn, after a loss to Solly Krieger in his very next contest, departed for light-heavyweight.

Conn spread himself too thinly to make either the top thirty at middleweight or the top fifteen at light-heavyweight but rather straddles both division’s – and even heavyweight – making an indelible pound-for-pound mark upon history.

#33 – TONY ZALE (67-18-2)

Tony Zale was the man who wound the rope that unravelled when the great Micky Walker vacated the middleweight title. He held the lineal championship in an astounding seven calendar years, a feat worthy of inclusion inside the top ten at the weight, were it not for the fact that the war interrupted Zale’s prime. He did not defend his title in 1942, 1943, 1944 or 1945, preferring to take a crack at the wonderful Billy Conn up at light-heavyweight before turning his attention to the Japanese in the wake of Pearl Harbour. He served in the navy.

Before the war, Zale was a force to be reckoned with, losing just one fight at middleweight between May of 1939 and enlisting, against an inspired Billy Soose. Among his victims was strap holder Al Hostak, who dropped Zale in the first round but also went to drop all five of the closing rounds in a non-title fight. This made a title-fight inevitable, and when it came, Zale didn’t miss his chance, breaking a supposedly below-par Hostak down gradually, forcing the referee’s intervention in the thirteenth.

With typical dramatic flair Zale, a private and by all accounts understated man outside of the ring, may have rescued himself from a draw in the tenth and final round by dropping the superb Fred Apostoli to win their non-title meeting, his finest win. After quickly dispatching a now broken Hostak in another fight and meeting some unranked competition, Zale legitimised his reign and unified a middleweight title that had been fractured since the retirement of Micky Walker, against Georgie Abrams. Abrams dropped Zale early but was a decisive loser as Zale met him with a savage body-attack for which he remains famous; this may have been his single best performance.

It was post-war that he achieved immortality, boxing in a famous trilogy with Rocky Graziano. I suspect that if Zale were in his pre-war prime there would have been no trilogy and that perhaps even one fight would have been enough; that aside, he lost the middle of three, reclaiming his middleweight championship before having his title blasted from him by Marcel Cerdan.

Generally held in higher regard than his placement here, it should be noted that I’ve recounted Zale’s wins against ranked contenders in this short appraisal in its entirety. He was a special middleweight but one who in no way earned the occasional top ten slot awarded him by historians and fans based upon what he actually did in the ring.

#32 – JAMES TONEY (76-9-3)

I googled James Toney’s name tonight with a view to a final review of some details to appear for his entry and found, to my surprise – to my distress – that he had a fight scheduled for that very night. A long time ago Toney’s menace dropped away from him and he became nothing more than a parody of himself; a pretender to his own throne where he had once sat as the most intimidating force in a very good middleweight division and, when Tyson was incarcerated for rape, in all of boxing.

“I fight with anger,” he once told a reporter. “I look at my opponent, I see my dad, so I have to take him out of there. I have to kill him.”

Toney badmouthed Michael Nunn all the way through the build up to their 1991 title fight, putting his hands on Nunn at the weigh in and threatening to “kill his bones”. Nunn, for his part, vowed to “punish” Toney in the ring for his many transgressions. Toney scowled his way to the ring and Nunn did indeed set out to punish him, but here my version of events and those of the judges part slightly. For the judges, Nunn dominated the next ten rounds of action whereas the way I see it, Nunn dominated early and Toney closed the gap late. None of this matters though, because after assuring his corner after the tenth that “I got him”, Toney dropped Nunn with a savage, winging hook and followed up with a hoodlum barrage of punches that left Nunn stricken. The lineal reign of Michael Nunn was over and the lineal reign of James Toney had begun.

He managed six successful defences which is deeply impressive…but – Toney was lucky.

He twice met with the wonderful Mike McCallum in protection of his title and each time the fights, the first ruled a draw, the second a majority decision for Toney, were so desperately close that any one of three decisions could reasonably have been rendered. Against top contender Reggie Johnson, his first defence, Toney ran out a legitimate winner but he needed to win the twelfth to take the decision. He was an uninspiring champion.

An uninspiring champion who was the beneficiary of a gift against David Tiberi, who dominated him in his fourth defence, Toney could have relinquished his title on any one of four occasions but should have done so against Tiberi, who was such a huge outsider going in that it was impossible to get odds on their fight.

Slick, fearless, interesting in his style and consistently in extremely close rounds with good fighters, Toney’s career is a contradiction; he is a fighter who both under-achieved and over-achieved and a champion who both proved his greatness and underwhelmed.

#31 – LLOYD MARSHALL (70-25-4)

Whether appraising Lloyd Marshall pound-for-pound (where I ranked him #83 all-time) or light-heavyweight (where I ranked him at #17) or here, at middleweight, it is a challenging task. Emerging footage of Marshall has illustrated a true gunslinger, a riffmaster general of whatever division he was gracing, a fighter as exciting and excellent and as flat-out different as anything else that has been seen.

He was also superb, serpentine, lethal, sudden and deadly. Big at the weight, he struggled to make the 160lb limit and was inarguably among the best super-middleweights in history many years before the division was conceived; he defeated Ezzard Charles while weighing 165lbs, Holman Williams at the same weight, Anton Chistoforidis at 168lbs – it is a prestigious list and one too lengthy to enter into here.

Adhering strictly to our criteria, which limits middleweight contests to 164lbs and below, Marshall is more limited by his size – but he did more than enough to be included here in the top forty.

Take Jake LaMotta, the Bronx Bull; a great middleweight by anyone’s standards – Marshall crushed him, outclassed him, cut his cheek, his nose and even rocked the man with perhaps the greatest chin in boxing history in the fifth round. Along with fellow greats Fritzie Zivic and Sugar Ray Robinson he would be the only man to beat the bull in the five year period that arguably constituted his savage prime.

Charley Burley, the Don of the Murderer’s Row that terrorised the welterweight and middleweight division in the 1940s, too, couldn’t quite fathom Marshall’s astonishing style, although a hairline fracture to the hand probably didn’t help the Pittsburgher. Marshall emerged with the hairline decision.

Surging aggression, as well as unpredictability, was his friend, as when he met Billy Soose, a fighter with huge experience who still had his best years in front of him in 1938. Despite a damaged eye, Marshall boiled into the breach left by Overlin’s apparent fatigue to take a narrow decision.

Other ranked men he bamboozled included Joe Carter and Jack Chase, both of whom fell to this jazz-man slaughterer of champions, but in truth he probably did not belong at middleweight and this, in combination with numerous losses, often coming against key opponents, limits his ranking here, despite genuine domination of some truly great middles.

Featured Articles

Avila Perspective, Chap. 323: Benn vs Eubank Family Feud and More

Next generation rivals Conor Benn and Chris Eubank Jr. carry on the family legacy of feudal warring in the prize ring on Saturday.

This is huge in British boxing.

Eubank (34-3, 25 KOs) holds the fringe IBO middleweight title but won’t be defending it against the smaller welterweight Benn (23-0, 14 KOs) on Saturday, April 26, at Tottenham Hotspur Stadium in London. DAZN will stream the Matchroom Boxing card.

This is about family pride.

The parents of Eubank and Benn actually began the feud in the 1990s.

Papa Nigel Benn fought Papa Chris Eubank twice. Losing as a middleweight in November 1990 at Birmingham, England, then fighting to a draw as a super middleweight in October 1993 in Manchester. Both were world title fights.

Eubank was undefeated and won the WBO middleweight world title in 1990 against Nigel Benn by knockout. He defended it three times before moving up and winning the vacant WBO super middleweight title in September 1991. He defended the super middleweight title 14 times before suffering his first pro defeat in March 1995 against Steve Collins.

Benn won the WBO middleweight title in April 1990 against Doug DeWitt and defended it once before losing to Eubank in November 1990. He moved up in weight and took the WBC super middleweight title from Mauro Galvano in Italy by technical knockout in October 1992. He defended the title nine times until losing in March 1996. His last fight was in November 1996, a loss to Steve Collins.

Animosity between the two families continues this weekend in the boxing ring.

Conor Benn, the son of Nigel, has fought mostly as a welterweight but lately has participated in the super welterweight division. He is several inches shorter in height than Eubank but has power and speed. Kind of a British version of Gervonta “Tank” Davis.

“It’s always personal, every opponent I fight is personal. People want to say it’s strictly business, but it’s never business. If someone is trying to put their hands on me, trying to render me unconscious, it’s never business,” said Benn.

This fight was scheduled twice before and cut short twice due to failed PED tests by Benn. The weight limit agreed upon is 160 pounds.

Eubank, a natural middleweight, has exchanged taunts with Benn for years. He recently avenged a loss to Liam Smith with a knockout victory in September 2023.

“This fight isn’t about size or weight. It’s about skill. It’s about dedication. It’s about expertise and all those areas in which I excel in,” said Eubank. “I have many, many more years of experience over Conor Benn, and that will be the deciding factor of the night.”

Because this fight was postponed twice, the animosity between the two feuding fighters has increased the attention of their fans. Both fighters are anxious to flatten each other.

“He’s another opponent in my way trying to crush my dreams. trying to take food off my plate and trying to render me unconscious. That’s how I look at him,” said Benn.

Eubank smiles.

“Whether it’s boxing, whether it’s a gun fight. Defense, offense, foot movement, speed, power. I am the superior boxer in each of those departments and so many more – which is why I’m so confident,” he said.

Supporting Bout

Former world champion Liam Smith (33-4-1, 20 KOs) tangles with Ireland’s Aaron McKenna (19-0, 10 KOs) in a middleweight fight set for 12 rounds on the Benn-Eubank undercard in London.

“Beefy” Smith has long been known as one of the fighting Smith brothers and recently lost to Eubank a year and a half ago. It was only the second time in 38 bouts he had been stopped. Saul “Canelo” Alvarez did it several years ago.

McKenna is a familiar name in Southern California. The Irish fighter fought numerous times on Golden Boy Promotion cards between 2017 and 2019 before returning to the United Kingdom and his assault on continuing the middleweight division. This is a big step for the tall Irish fighter.

It’s youth versus experience.

“I’ve been calling for big fights like this for the last two or three years, and it’s a fight I’m really excited for. I plan to make the most of it and make a statement win on Saturday night,” said McKenna, one of two fighting brothers.

Monster in L.A.

Japan’s super star Naoya “Monster” Inoue arrived in Los Angeles for last day workouts before his Las Vegas showdown against Ramon Cardenas on Sunday May 4, at T-Mobile Arena. ESPN will televise and stream the Top Rank card.

It’s been four years since the super bantamweight world champion performed in the US and during that time Naoya (29-0, 26 KOs) gathered world titles in different weight divisions. The Japanese slugger has also gained fame as perhaps the best fighter on the planet. Cardenas is 26-1 with 14 KOs.

Pomona Fights

Super featherweights Mathias Radcliffe (9-0-1) and Ezequiel Flores (6-4) lead a boxing card called “DMG Night of Champions” on Saturday April 26, at the historic Fox Theater in downtown Pomona, Calif.

Michaela Bracamontes (11-2-1) and Jesus Torres Beltran (8-4-1) will be fighting for a regional WBC super featherweight title. More than eight bouts are scheduled.

Doors open at 6 p.m. For ticket information go to: www.tix.com/dmgnightofchampions

Fights to Watch

Sat. DAZN 9 a.m. Conor Benn (23-0) vs Chris Eubank Jr. (34-3); Liam Smith (33-4-1) vs Aaron McKenna (19-0).

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

Featured Articles

Floyd Mayweather has Another Phenom and his name is Curmel Moton

Floyd Mayweather has Another Phenom and his name is Curmel Moton

In any endeavor, the defining feature of a phenom is his youth. Philadelphia Phillies outfielder Bryce Harper was a phenom. He was on the radar screen of baseball’s most powerful player agents when he was 14 years old.

Curmel Moton, who turns 19 in June, is a phenom. Of all the young boxing stars out there, wrote James Slater in July of last year, “Curmel Moton is the one to get most excited about.”

Moton was born in Salt Lake City, Utah. His father Curtis Moton, a barber by trade, was a big boxing fan and specifically a big fan of Floyd Mayweather Jr. When Curmel was six, Curtis packed up his wife (Curmel’s stepmom) and his son and moved to Las Vegas. Curtis wanted his son to get involved in boxing and there was no better place to develop one’s latent talents than in Las Vegas where many of the sport’s top practitioners came to train.

Many father-son relationships have been ruined, or at least frayed, by a father’s unrealistic expectations for his son, but when it came to boxing, the boy was a natural and he felt right at home in the gym.

The gym the Motons patronized was the Mayweather Boxing Club. Curtis took his son there in hopes of catching the eye of the proprietor. “Floyd would occasionally drop by the gym and I was there so often that he came to recognize me,” says Curmel. What he fails to add is that the trainers there had Floyd’s ear. “This kid is special,” they told him.

It costs a great deal of money for a kid to travel around the country competing in a slew of amateur boxing tournaments. Only a few have the luxury of a sponsor. For the vast majority, fund raisers such as car washes keep the wheels greased.

Floyd Mayweather stepped in with the financial backing needed for the Motons to canvas the country in tournaments. As an amateur, Curmel was — take your pick — 156-7 or 144-6 or 61-3 (the latter figure from boxrec). Regardless, at virtually every tournament at which he appeared, Curmel Moton was the cock of the walk.

Before the pandemic, Floyd Mayweather Jr had a stable of boxers he promoted under the banner of “The Money Team.” In talking about his boxers, Floyd was understated with one glaring exception – Gervonta “Tank” Davis, now one of boxing’s top earners.

When Floyd took to praising Curmel Moton with the same effusive language, folks stood up and took notice.

Curmel made his pro debut on Sept. 30, 2023, at the T-Mobile Arena in Las Vegas on the undercard of the super middleweight title fight between Canelo Alvarez and Jermell Charlo. After stopping his opponent in the opening round, he addressed a flock of reporters in the media room with Floyd standing at his side. “I felt ready,” he said, “I knew I had Floyd behind me. He believes in me. I had the utmost confidence going into the fight. And I went in there and did what I do.”

Floyd ventured the opinion that Curmel was already a better fighter than Leigh Wood, the reigning WBA world featherweight champion who would successfully defend his belt the following week.

Moton’s boxing style has been described as a blend of Floyd Mayweather and Tank Davis. “I grew up watching Floyd, so it’s natural I have some similarities to him,” says Curmel who sparred with Tank in late November of 2021 as Davis was preparing for his match with Isaac “Pitbull” Cruz. Curmell says he did okay. He was then 15 years old and still in school; he dropped out as soon as he reached the age of 16.

Curmel is now 7-0 with six KOs, four coming in the opening round. He pitched an 8-round shutout the only time he was taken the distance. It’s not yet official, but he returns to the ring on May 31 at Mandalay Bay in Las Vegas where Caleb Plant and Jermall Charlo are co-featured in matches conceived as tune-ups for a fall showdown. The fight card will reportedly be free for Amazon Prime Video subscribers.

Curmel’s presumptive opponent is Renny Viamonte, a 28-year-old Las Vegas-based Cuban with a 4-1-1 (2) record. It will be Curmel’s first professional fight with Kofi Jantuah the chief voice in his corner. A two-time world title challenger who began his career in his native Ghana, the 50-year-old Jantuah has worked almost exclusively with amateurs, a recent exception being Mikaela Mayer.

It would seem that the phenom needs a tougher opponent than Viamonte at this stage of his career. However, the match is intriguing in one regard. Viamonte is lanky. Listed at 5-foot-11, he will have a seven-inch height advantage.

Keeping his weight down has already been problematic for Moton. He tipped the scales at 128 ½ for his most recent fight. His May 31 bout, he says, will be contested at 135 and down the road it’s reasonable to think he will blossom into a welterweight. And with each bump up in weight, his short stature will theoretically be more of a handicap.

For fun, we asked Moton to name the top fighter on his pound-for-pound list. “[Oleksandr] Usyk is number one right now,” he said without hesitation,” great footwork, but guys like Canelo, Crawford, Inoue, and Bivol are right there.”

It’s notable that there isn’t a young gun on that list. Usyk is 38, a year older than Crawford; Inoue is the pup at age 32.

Moton anticipates that his name will appear on pound-for-pound lists within the next two or three years. True, history is replete with examples of phenoms who flamed out early, but we wouldn’t bet against it.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

Featured Articles

Arne’s Almanac: The First Boxing Writers Assoc. of America Dinner Was Quite the Shindig

The first annual dinner of the Boxing Writers Association of America was staged on April 25, 1926 in the grand ballroom of New York’s Hotel Astor, an edifice that rivaled the original Waldorf Astoria as the swankiest hotel in the city. Back then, the organization was known as the Boxing Writers Association of Greater New York.

The ballroom was configured to hold 1200 for the banquet which was reportedly oversubscribed. Among those listed as agreeing to attend were the governors of six states (New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Connecticut, and Maryland) and the mayors of 10 of America’s largest cities.

In 1926, radio was in its infancy and the digital age was decades away (and inconceivable). So, every journalist who regularly covered boxing was a newspaper and/or magazine writer, editor, or cartoonist. And at this juncture in American history, there were plenty of outlets for someone who wanted to pursue a career as a sportswriter and had the requisite skills to get hired.

The following papers were represented at the inaugural boxing writers’ dinner:

New York Times

New York News

New York World

New York Sun

New York Journal

New York Post

New York Mirror

New York Telegram

New York Graphic

New York Herald Tribune

Brooklyn Eagle

Brooklyn Times

Brooklyn Standard Union

Brooklyn Citizen

Bronx Home News

This isn’t a complete list because a few of these papers, notably the New York World and the New York Journal, had strong afternoon editions that functioned as independent papers. Plus, scribes from both big national wire services (Associated Press and UPI) attended the banquet and there were undoubtedly a smattering of scribes from papers in New Jersey and Connecticut.

Back then, the event’s organizer Nat Fleischer, sports editor of the New York Telegram and the driving force behind The Ring magazine, had little choice but to limit the journalistic component of the gathering to writers in the New York metropolitan area. There wasn’t a ballroom big enough to accommodate a good-sized response if he had extended the welcome to every boxing writer in North America.

The keynote speaker at the inaugural dinner was New York’s charismatic Jazz Age mayor James J. “Jimmy” Walker, architect of the transformative Walker Law of 1920 which ushered in a new era of boxing in the Empire State with a template that would guide reformers in many other jurisdictions.

Prizefighting was then associated with hooligans. In his speech, Mayor Walker promised to rid the sport of their ilk. “Boxing, as you know, is closest to my heart,” said hizzoner. “So I tell you the police force is behind you against those who would besmirch or injure boxing. Rowdyism doesn’t belong in this town or in your game.” (In 1945, Walker would be the recipient of the Edward J. Neil Memorial Award given for meritorious service to the sport. The oldest of the BWAA awards, the previous recipients were all active or former boxers. The award, no longer issued under that title, was named for an Associated Press sportswriter and war correspondent who died from shrapnel wounds covering the Spanish Civil War.)

Another speaker was well-traveled sportswriter Wilbur Wood, then affiliated with the Brooklyn Citizen. He told the assembly that the aim of the organization was two-fold: to help defend the game against its detractors and to promote harmony among the various factions.

Of course, the 1926 dinner wouldn’t have been as well-attended without the entertainment. According to press dispatches, Broadway stars and performers from some of the city’s top nightclubs would be there to regale the attendees. Among the names bandied about were vaudeville superstars Sophie Tucker and Jimmy Durante, the latter of whom would appear with his trio, Durante, (Lou) Clayton, and (Eddie) Jackson.

There was a contraction of New York newspapers during the Great Depression. Although empirical evidence is lacking, the inaugural boxing writers dinner was likely the largest of its kind. Fifteen years later, in 1941, the event drew “more than 200” according to a news report. There was no mention of entertainment.

In 1950, for the first time, the annual dinner was opened to the public. For $25, a civilian could get a meal and mingle with some of his favorite fighters. Sugar Ray Robinson was the Edward J. Neil Award winner that year, honored for his ring exploits and for donating his purse from the Charlie Fusari fight to the Damon Runyon Cancer Fund.

There was no formal announcement when the Boxing Writers Association of Greater New York was re-christened the Boxing Writers Association of America, but by the late 1940s reporters were referencing the annual event as simply the boxing writers dinner. By then, it had become traditional to hold the annual affair in January, a practice discontinued after 1971.

The winnowing of New York’s newspaper herd plus competing banquets in other parts of the country forced Nat Fleischer’s baby to adapt. And more adaptations will be necessary in the immediate future as the future of the BWAA, as it currently exists, is threatened by new technologies. If the forthcoming BWAA dinner (April 30 at the Edison Ballroom in mid-Manhattan) were restricted to wordsmiths from the traditional print media, the gathering would be too small to cover the nut and the congregants would be drawn disproportionately from the geriatric class.

Some of those adaptations have already started. Last year, Las Vegas resident Sean Zittel, a recent UNLV graduate, had the distinction of becoming the first videographer welcomed into the BWAA. With more and more people getting their news from sound bites, rather than the written word, the videographer serves an important function.

The reporters who conducted interviews with pen and paper have gone the way of the dodo bird and that isn’t necessarily a bad thing. A taped interview for a “talkie” has more integrity than a story culled from a paper and pen interview because it is unfiltered. Many years ago, some reporters, after interviewing the great Joe Louis, put words in his mouth that made him seem like a dullard, words consistent with the Sambo stereotype. In other instances, the language of some athletes was reconstructed to the point where the reader would think the athlete had a second job as an English professor.

The content created by videographers is free from that bias. More of them will inevitably join the BWAA and similar organizations in the future.

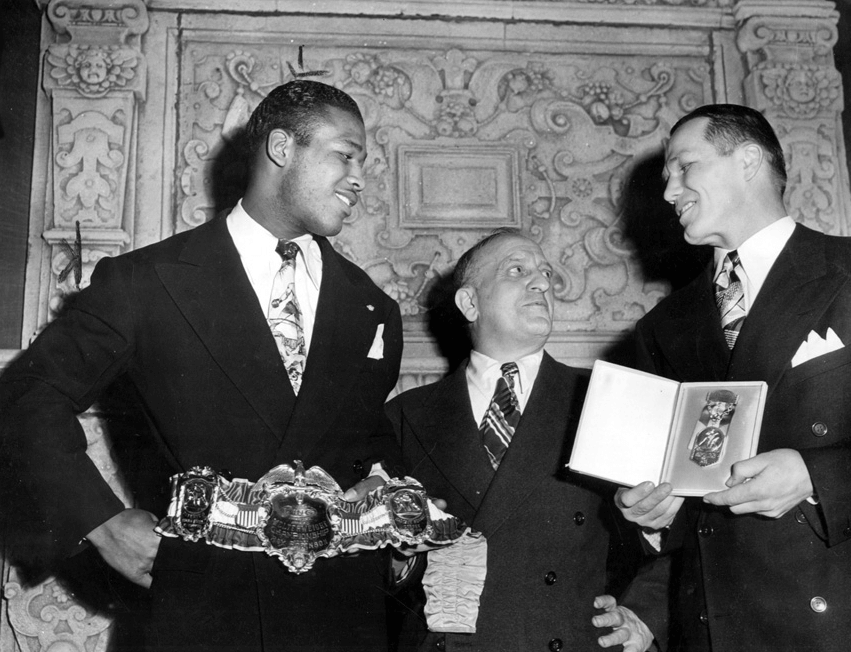

Photo: Nat Fleischer is flanked by Sugar Ray Robinson and Tony Zale at the 1947 boxing writers dinner.

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 319: Rematches in Las Vegas, Cancun and More

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRingside at the Fontainebleau where Mikaela Mayer Won her Rematch with Sandy Ryan

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoWilliam Zepeda Edges Past Tevin Farmer in Cancun; Improves to 34-0

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoHistory has Shortchanged Freddie Dawson, One of the Best Boxers of his Era

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 320: Women’s Boxing Hall of Fame, Heavyweights and More

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoResults and Recaps from Las Vegas where Richard Torrez Jr Mauled Guido Vianello

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoFilip Hrgovic Defeats Joe Joyce in Manchester

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoWeekend Recap and More with the Accent of Heavyweights