Featured Articles

The Fifty Greatest Middleweights of All Time Part Three: 30-21

Great middleweights outrank great fighters on this list.

That’s why the likes of Roy Jones and Billy Conn languish behind Gene Fullmer and Nino Benvenuti. A fighter’s contribution at the fighting weight that was middleweight is all that really matters.

And what a weight. If it isn’t clear by now, it will be at the end of this installment; middleweight is ridiculous, stacked to the gunnels with the type of fighting quality that just doesn’t exist at either heavyweight or light-heavyweight.

For the casual fan – the life-blood of the sport – there will be one or two names here that you are not familiar with. I hope you come to love these fighters like I do. For The Sweet Science’s more hardcore readership, I hope you enjoy seeing some of the less glamourous 160lb warriors receiving overdue credit.

#30 – NINO BENVENUTI (82-7-1)

In the end, Benvenuti was destroyed by Carlos Monzon, as was just about everyone unlucky enough to meet with the Argentine in the seventies, but in the sixties were kinder to him. Benvenuti lost just three times in that decade, once to Ki-Soo Kim at light-middleweight in ‘66; to Dick Tiger up at light-heavyweight in ’69; and once at middleweight to Emile Griffith.

Griffith, one of the greatest welterweights, also carved out for himself a superb career at middleweight and it was he that welcomed Benvenuti, an Italian citizen who had been born in Slovenia, to America. If Benvenuti felt stage-fright he gave no sign of it in ripping the title from Griffith in what may have been the 1967 fight for the year; Benvenuti all but dominated Griffith with a career’s best jab and the snaking straight-right which he was most famous for – but most often with a rare but beautiful counter-right-hand that hurt the champion repeatedly. A rematch followed five months later in which Griffith abandoned the rushing attack that had brought him to grief in the first fight in preference of a steady pressure and a beautiful left-handed attack; the strength of Griffith’s jab was variety and Benvenuti was never allowed to settle. It brought Griffith the narrowest of majority decisions, a short right hand that flashed Benvenuti in the eighth the possible difference-maker.

Their third, fought the following year, was part clinic, part barroom brawl just as the first two had been but it was Benvenuti who emerged from the fight with the majority decision on this occasion after sending Griffith spinning across the ring and onto his backside in the ninth – and then surviving his brutal rally in the fifteenth. Benvenuti defended the title on four separate occasions including perhaps his best performance, an eleventh round knockout of the streaking wonder that was Luis Manuel Rodriguez, who he stopped with a single left hook while on the verge of being pulled with cuts. Other ranked men he disposed of in less spectacular fashion include Doyle Baird, Fraser Scott, Ferd Hernandez, Don Fullmer and Luis Folledo.

#29 – EMILE GRIFFITH (85-24-2)

The wonderful welterweight and light-middleweight champion Emile Griffith first elected to dip his toe into the choppier waters of middleweight not against soft-sell opposition designed to give him the feel for the bigger division but against ranked men, taking on and beating old foe Denny Moyer and the recently eliminated Don Fullmer back to back in August and October of 1962. Griffith couldn’t quite dominate Moyer, who forced his way back into their third and final fight savagely in the eighth and ninth rounds, but Griffith was always better suited to the habitat Moyer favoured, up close where identifying punching opportunity and accuracy, Griffith’s two greatest attributes, were at a premium. This was a problem hanging over Griffith, however, given that he was a natural light-middleweight moving up in search of glory and money; inside is the last place you want to be against a bigger opponent, on paper.

Griffith moved beautifully, too, and can be named among the most legitimate of polished all-rounders when fresh, but as soon as fatigue began to find him, it was to the inside that he went. This was fine in the early 1960s with the title passing merrily between Paul Pender and Terry Downes, both of whom Griffith likely could have out-boxed up close, but when the title started to move between Dick Tiger and Joey Giardello, Griffith seemed without hope of ever picking up the title. Boxing inside against Tiger, especially, was akin to surrender.

This is what Emile Griffith did, though, when his status as the welterweight champion of the world and his performances against borderline ranked fighters proved enough to get him into a Madison Square Garden ring with Tiger in 1965. Not for the first half of the fight, though. In the first half of the fight, Griffith worked to keep the fight at range where he did not, could not dominate against Tiger, very probably the superior technician. But he also, with generalship and mobility, prevented Tiger from dominating – his whole fight plan was one big interference with the great champion’s own.

So it was that when Tiger started to dial his jab in, Griffith stepped inside on an apparent suicide mission. But legendary trainer Gil Clancy had gambled, and convinced an uncertain Griffith, that he had and even at welterweight had had, the strength of a middleweight. To his own surprise, Griffith was able to match Tiger for spells, even pushing him back in rounds seven, eight and eleven. Even though he was handled on occasions, it was Tiger, not he, who visited the canvas in round now. The knockdown was the very definition of flash but it was legitimate, Tiger’s right knee buckling behind a one-two for the first visit to the canvas of his storied career.

Griffith got the decision in a fight that could have been scored any one of three ways and although it should be noted that most ringside reporters saw it for Tiger, film shows a desperately close encounter which I think can validly be given to Griffith (for full disclosure I should mention that I have never been able to source a copy of this fight that has round five – any readers who have and feel like sharing should feel free to email me at m.mcgrain@hotmail.co.uk!).

Meetingt with Joey Archer for his first defence, Griffith took the opposite attitude and attacked, bullied and handled his bigger opponent for a narrow decision deemed controversial in some quarters; so he re-matched Archer and beat him again; then began his three fight series with Benvenuti.

Griffith began to suffer up at middleweight and as the 1970s dawned, it would be Monzon who would be Griffith’s chief-tormentor; but despite a certain inconsistency in his middleweight work that did not exist for him at welterweight, he continued to add to resume in the new decade, including men like Stanley Hayward (who also bested him once) and Bennie Briscoe.

A two-time world champion, he ranks here just above Benvenuti despite his losses to him based upon that narrow victory over Tiger; the top twenty is an impossibility for him due to the avalanche of a knockout he suffered at the hands of Rubin Carter very early in his middleweight career.

#28 – FRANK KLAUS (33-5-2; Newspaper Decisions 35-9-12)

Frank Klaus enjoyed an argument in the ring and he liked it up close, personal, sometimes using his head and elbows as reservists to his vicious infighting attack. It made him one of the most formidable middleweights of the post-Ketchel era and one of the few claimants to have lifted the legitimate title.

He is also a fighter that, like Jeff Smith (as discussed in Part One), inexplicably ranks in the top ten of many of the old time historians. On the one hand, Klaus was impressive over the six round distance, boxing a draw with Stanley Ketchel and posting a win over Billy Papke; on the other hand he lost twice to our #50, Hugo Kelly, who beat him once over the six round distance in 1909 and the twelve round distance in 1910. One the one hand he was, as noted, the lineal middleweight titleholder but on the other, he won it on a disqualification in a fight that he was reportedly edging with Billy Papke; furthermore, he had won his previous fight against Georges Carpentier – but also on a disqualification in a fight he was reportedly losing. Klaus’s record is impressive, but needs qualifying in some respects.

Still, there is little to complain about so far as his series with the great Jack Dillon is concerned. Their first fight occurred in Pittsburgh in 1911 over six rounds; generally it is recorded as a draw (or no decision) with some secondary sources suggesting Dillon got the better of it. In 1912 they met over twenty rounds in a fight so foul as to be nondescript outside of this and the decision was awarded to the less flagrant of the two, which happened to be Klaus. They fought a rematch just three months later over ten and it was Klaus again who got the nod in a tamer affair that saw him outfight Dillon on the inside, a phenomenal achievement, for the second consecutive time. Dillon fled the middleweight division in his wake and Klaus went on to claim the title.

He holds other excellent wins at the weight including Jimmy Gardner, Leo Houck, Eddie McGoorty, Johnny Thompson and Jack Sullivan. Toss in Dillon and Papke and that draw with Ketchel and you are talking about a fighter who met an overwhelming majority of the best of his era and got the better of most of them.

#27 – BERT LYTELL (71-23-7)

“The Beast of Stillman’s Gym”, Bert Lytell, is probably the most underrated fighter on this list. Ranked here ahead of men who appear higher up on more traditional rankings, Lytell has built a resume so superior to that of the likes of Tony Zale or Marcel Cerdan I feel it reveals a bias in the old-time historians – to be respected, valued, cherished for their contributions to the sport which are enormous – to the champions. Simply put, Lytell did better work in the middleweight division than many of these men. His paper record is deceptive; most of his losses occurred past-prime up at light-heavyweight.

Matched tough early, things reached an absurd, almost surreal level of the impossible when, with his record by Boxrec standing at just 18-4-2, Lytell was matched with a prime Jake LaMotta. LaMotta, an absurdity of violence and pressure in the ring, is to be credited with his determination to match the best of the Black Murderer’s row but one should be very careful about crediting him with a victory over the green Lytell as it is recorded in his record in April of 1945. Lytell seems to have duped the bull with a combination of aggression and patience that belied his tender beginnings as a professional, with two out of three officials seeing it to LaMotta, but with numerous ringside reports indicating that Lytell, a 10-1 underdog, deserved the decision; the AP report referred to LaMotta as “baffled” by the normally warlike Lytell’s more subtle skills and only a late rally and some controversial judging spared history what might have been a very severe twist. Lytell spent years trying and failing to get LaMotta back into the ring.

Absurdly, Lytell then went out of his way to embark upon a series with one of the few middleweights of that incredible era more dangerous to a young prospect than LaMotta, Holman Williams. Williams was shortly to begin a final fade into mortality but when Lytell first met him just four months after his close encounter with LaMotta, he was coming off a victory over fellow great Charley Burley. Lytell, boxing in rarefied air visited without disaster by only a few men and perhaps none of such little experience, followed the probable loss by officiating against all-time great LaMotta with a draw against the all-time great Holman Williams.

A bizarre exchange of roles followed, with Lytell boxing long and Williams stepping inside to rescue the fight on the cards and then dominating the younger man with a body-attack in the rematch. Lytell persisted with this out-boxing style in their third encounter fought in 1946. The only men to have beaten Williams in the previous two years were a light-heavyweight Archie Moore; the Cocoa Kid, who Williams then avenged himself upon; Lloyd Marshall, with whom he went 1-1; and the wonderful Eddie Booker, with whom he also shared a pair. He had defeated Jack Chase, Charley Burley, Young Gene Buffalo, Kid Tunero, Aaron Wade and Joe Carter in that same period but Lytell blasted himself to a points victory. A meaningless fourth fight followed, the creaking Williams dropping a series to Lytell, who had become either the new rent-collector at the gates of the Row or the next Archie Moore.

It was to be the former. No man but Moore could produce both the longevity and resiliency to cope with long-term residency of that fistic underworld for more than a few years and things got no easier for Lytell; he went 1-1 with the incredible Burley; he went an outstanding 3-0 with Cocoa Kid and although this is tempered by his loss to Aaron Wade, his record against his fellow residents was an exceptional one. Ranked types from the other side of that demarcation line – guys like Major Jones, Sam Baroudi and Sylvester Perkins – were also matched and bettered.

Lytell is ranked third among the middleweights of the Murderer’s Row, and this has surprised me; I expected Lloyd Marshall, but his inconsistencies in marriage with Lytell’s unerring desire to be matched with the best see him scrape in ahead. If the two had met, perhaps that would have helped to settle matters between them, but it seems even on the Row there were those that eyed one-another warily from opposing street corners.

#26 – LES DARCY (46-4)

Les Darcy was but twenty-one years old when he died. His lofty ranking is one of the most incredible aspects of what might turn out to be the deepest of the top fifties for the traditional weight divisions. His presence in this slot is a miracle of potential and of youthful vibrancy. Still, it is a fact that for many, Darcy’s position will be too low; for the Australian history buff, there is often only one middleweight that matters.

But it is unquestionably the fact that Darcy died before he could fulfil his potential, and also before he could be matched with the era’s best middleweight, Mike Gibbons, or the best of the coming generation, Harry Greb. Nevertheless, the mark he made was significant, including an excellent performance against former world middleweight champion George Chip. Chip, coming off a ten round newspaper decision victory against a green Greb, was a former world champion and remained a significant scalp. Darcy followed his left inside or baited Chip to the same effect, before dominating exchanges in the pocket, finding creases and cracks for punches everywhere. He appears reasonably easy to find, as he did against the wonderful Indiana Wasp, Jimmy Clabby, another significant scalp, but equal to whatever his opponent could dish out and consistent in outlanding him where it mattered.

Dominant against world class opposition, Darcy went about 25-3 as a middle, avenging all losses and defeating in addition to Clabby and Chip the excellent Eddie McGoorty. He failed to build a resume of great meaning given his failure to make matches in the USA (then, as now, the hub of all things fistic) and far more pertinently his untimely death, but his excellence on film (reasoned comparisons to Jack Johnson have been made) and his clear superiority over the opposition he did meet in the final years of his life, in addition to the esteem in which he is held by those who saw him box, means a position in the twenties is warranted.

#25 – MIKE O’DOWD (51-7-3; Newspaper Decisions 42-10-3)

Mike O’Dowd had the face of a fighter. The nose hammered into an indeterminate feature; the thin lips; the shovel flat face rubbed indifferently onto a bullet-shaped head; the jaw vanishing into his skull; and the thousand-yard stare.

He held a punch like a fighter too, stopped just once in more than one-hundred contests. He went a superb 10-2-1 in middleweight title fights. With raw statistics like these the reader may reasonably ask: why is O’Dowd ranked no higher?

Evidence in support of a higher ranking is plentiful outside of O’Dowd’s raw equipment and statistical achievements. First and foremost is his astonishing series victory over Mike Gibbons. Gibbons is an immortal of the middleweight division and I’m sure I give little away in saying he will appear very close to the pinnacle of this list, and O’Dowd was the only man to triumph in a series versus Gibbons. Their first fight was desperately close, with many ringsiders speaking in favour of a draw or a Gibbons win but a majority favouring O’Dowd according to reports. Their second fight, fought two years later, by which time the title had departed O’Dowd, was clear in favour of Gibbons; their rubber match fought in 1922 was the only meeting between the two in which an official decision was rendered, and that decision went to O’Dowd.

Another key win over the wonderful Jeff Smith (ranked at #43), all aggression and in part defined by the right hand to the body. This was typical of the type of performances O’Dowd turned in between 1917 and 1920 when he was the middleweight champion of the world although despite a hard-charging style he remained difficult to catch clean.

Two factors hurt O’Dowd and pull him up short. First of all, when he lost the title it was to one of the most underwhelming champions in middleweight history, Johnny Wilson, and despite the fact that he got two chances to undo that damage in rematches, he was always befuddled by Wilson’s southpaw stylings and unable to overcome his jab. Secondly, O’Dowd struggled desperately with the two best welterweights of his era. Despite a big size advantage he actually lost a series to defensive genius Jack Britton and dropped two newspaper decisions to Britton’s nemesis Ted Lewis. These black marks tug a top thirty resume back into the densely packed ranks of this section.

#24 – GENE FULLMER (55-6-3)

Slate-faced and bull-necked, Fullmer boxed with a tactical indifference to even the hardest of punches but such was his durability and determination that he became one of the four men to hold the middleweight title in the year of 1957. A cynic might argue that Fullmer, like Carmen Basilio, only picked up the title because of the inconsistencies of the late incarnation of Sugar Ray Robinson but Robinson remains Robinson and in slogging his way to the middleweight title, Fullmer became one of the definitive middleweight battletanks. Without the layered counter-punching abilities of someone like Dick Tiger or the full-blown work-rate of Jake LaMotta, Fullmer had to rely on durability and heart to perhaps an even greater degree than those two immovable legends. But what Fullmer did have was manoeuvrability, a certain lightness of feet that made his choice of style seem curious at times. Boxing is a rarity in sport in that the competitors are the men they are first and the athletes they are second, and so Fullmer neglected to use that surety of footwork to rescue him from pain and instead walked into fire and tried to out-maul his world class opposition.

Between 1956 and 1961 he out-mauled everybody, losing just once to Sugar Ray Robinson, whom he twice bested for a final ledger of 2-2-1. Robinson’s series with Fullmer described his decline really, but on the eve of their first fight from January 1957 Robinson was in fine form having twice bested Bobo Olsen in world-title fights. Whatever his precise condition, dethroning the one and only Sugar Ray always carries with it a certain cachet and this Fullmer did, betting him reasonably clearer on the judge’s scorecards in a fight made close to my eyes by a vicious uppercut to the body repeatedly employed by the defending champion; but Fullmer had the look of a fighter who could eat even these punches all night, and he did, lifting the world’s middleweight title in the process. The second fight between them ended in devastating fashion in Robinson’s favour as he knocked Fullmer out in the fifth with his famous “perfect left hook”, all the more shocking for the fact that Fullmer looked so undisturbed by Robinson’s best in that first fight. The two met again in 1960 in an unpopular draw making a fourth fight necessary; Robinson, by now over forty and broke, had nothing left to give and Fullmer rolled him over in fifteen.

Perched perfectly between Robinson and another great champion, Dick Tiger, no sooner had he seen of the first then he had to make war with the second – this was a contest he could not win as even his prestigious strength saw him out-matched by the monstrous Nigerian, who out-muscled and bulled the previously impervious Utah man. Still, Fullmer has a truly impressive ledger and took on and defeated multiple top five contenders, including Rocky Castellani, Ralph Jones, Spider Webb, Charles Humez and the superb Carmen Basilio, who he twice stopped in brutal encounters. He was unlucky not to get the nod over the superb Joey Giardello when they met in 1960, ten of eleven ringside reporters favouring Fullmer according to The Milwaukee Sentinel, but overall, Fullmer got far more out of his career than a fighter with his limitations had any business achieving.

He was a hard night’s work for any man who ever weighed 160lbs.

#23 – BILLY PAPKE (37-11-5; Newspaper Decisions 3-6-1)

Speaking of a hard night’s work: Billy Papke.

He had to shoot himself in the heart three times to end his torrid life on Thanksgiving Day 1936, finally succumbing to the terrible disarray of his personal life. Once upon a time, he had boxed with a savagery fitting of the man he would become, the man who would slay his ex-wife before taking his own life, a man so brutal that he was able to take the great Stanley Ketchel apart at the seams so completely that some wondered if he would ever be put back together again.

Ketchel had already defeated Papke once in a torrid ten rounds in April of 1908; the litany of excuses he laid at the door of pressmen as he relentlessly pursued a rematch is typical of those adopted by a fighter. Ketchel meanwhile was standing on tiptoe and peering past his seething nemesis at world heavyweight champion Billy Papke. Papke saw his chance, and if it was borne, as the legend holds, of a smash to Ketchel’s throat before the bell was rung, this is not reflected in any of the ringside reports I have seen. Instead these reports describe a fighter possessed in out-fighting, out-slugging, and, yes, out-boxing the ultimate furnace-bound middleweight Stanley Ketchel. Ketchel dominated their series 3-1, but Papke tore a primed Ketchel into punch sized pieces in their second encounter to become the middleweight champion of the world.

He was not given the opportunity to make any successful defences as a rampant Ketchel vanished into the desert and re-emerged to exact a terrible revenge just months later and, I suspect, broke Papke in the way some thought Papke had broken him. But he still did some good work, beating the likes of Willie Lewis, out of New York and sporting an excellent record when Papke blasted him out in just three; Joe Thomas, who held a newspaper decision over Frank Klaus, but who Papke stopped in the sixteenth round of a savage encounter in 1910; the excellent Dave Smith, who was unbeaten and would go on to defeat Battling Levinksy and Jimmy Clabby; an easy decision over former pound-for-pounder Jack “Twin Sullivan”, and many other worthies. He also went unbeaten in a four fight series with Hugo Kelly, and for all that he is defined by his other four fight series with Ketchel, achieved a superb resume. Despite a disastrous run in to his career – he lost twelve of his last eighteen fights – he’s earned his spot in the twenties.

#22 – JOEY GIARDELLO (99-27-8)

Joey Giardello was one of the middleweight division’s greatest survivors. After turning professional in the late forties, Giardello spent years slogging his way through a hellish apprenticeship that saw him turn out sixteen times in 1950 alone. Naturally there were losses; naturally, for a fighter of his quality he broke into the Ring rankings in 1952. He would remain there for most of the fifties and for much of the 1960s, including a spell as champion despite his sharing an era with the terrifying Dick Tiger, a fighter he had to face on no fewer than four occasions. Like Tiger, his long wrestle with contendership makes his eventual rise to the summit more and not less impressive.

Giardello’s arrival looked to be anointed by his superb 1954 stoppage of the ranked puncher and favourite Willie Troy in a fight in which Giardello found the point of Troy’s chin from the first, all the while taking the best the Virginian could dish out. Troy was saved by the bell in both the first and the second but Giardello slowly bricked him up with a scything, brutal right-hand and a cuffing, debilitating left all while giving ground. Troy was all in after seven and rightly plucked from danger by referee Al Berl.

Giardello came undone in his next fight with the fearless and often brilliant Frenchman Pierre Langlois but bounced back with a minor controversy in his win over Bobby Jones, also ranked, but tumbled down the rabbit hole of contendership once more after losing out to Charley Cotton; and so it went for a fighter who seemed perennially one fight away from a title shot.

In many ways, Giardello is the anti-Cerdan. He did not, like the Frenchman, go unbeaten, but nor was his middleweight journey tragically cut short. He fought there for years, meeting more ranked men and accruing losses. Where Giardello edges ahead for me is in the twilight of his career when, upon defeating an aged Sugar Ray Robinson, he found himself in the ring for a third time with Dick Tiger with whom he had previously gone 1-1; now the title was at stake.

Aged 33, a veritable pensioner for the era given his sixteen years as a professional behind him, he did not fail in his last best chance at a title; he boxed his way to a decision over Tiger and then cemented his reputation as fearless in matching the destructive Rubin Carter in his first defence. He could not manage another, losing out to a brilliant Tiger in a fourth and final contest in 1965, an astonishing ten years after his defeat of Willie Troy.

Giardello’s career is simply too storied to recount here entirely but he can be surmised as being perhaps not among the greatest champions in middleweight history, but very much among the greatest contenders. I’ve nudged him in ahead of Gene Fullmer here, with whom he fought a savage draw in 1960, based upon his at least partial taming of Tiger.

#21 – KEN OVERLIN (135-19-9)

If Ken Overlin could punch he may very well have appeared in the final installment of this list. A veteran of more than 160 contests he lost just nineteen, but even more astonishing is that he won 135 while scoring just twenty-three knockouts.

This is a KO percentage rather less than that of Paul Malignaggi.

Despite this enormous handicap, Overlin defeated #2 contender Paul Pirrone, the coming George Black, ranked men Ben Brown and Al Quaill, Nate Bolden, strap-holder Ceferino Garcia, top five contender Steve Belloise, Al Hostak, the all-time great Ezzard Charles and the all-time great Fred Apostoli. Charles and Apostoli would both go on to get considerably better than they were when Overlin toyed with them, but the way he inflicted his left hand on two of the great boxers of that era was a fantastic endorsement for Overlin’s jab, which rarely let him down.

A strapholder rather than a defining champion, Overlin had his belt taken from him in preposterous circumstances, dropping a home-state decision to Billy Soose in a non-title fight in 1940; this positioned Soose for a 1941 shot at Overlin, who was robbed for a second time in a fight that so defied expectations that it led The New York Times to label Soose as appearing “retarded.” The political incorrectness of this remark aside, it was clear to most ringsiders that Overlin deserved the decision. The fact that many of his finest victories, including that schooling of Ezzard Charles, came after these apparent twin-robberies it is fair to speculate as to what sort of champion Overlin might have become if he had been allowed to obtain the type of seniority that comes with championship longevity; that it was not to be is perhaps one of middleweight history’s greatest injustices.

Something of a nearly-man then, despite all his success; a fitting gatekeeper to the top twenty, perhaps.

Featured Articles

Avila Perspective, Chap. 323: Benn vs Eubank Family Feud and More

Next generation rivals Conor Benn and Chris Eubank Jr. carry on the family legacy of feudal warring in the prize ring on Saturday.

This is huge in British boxing.

Eubank (34-3, 25 KOs) holds the fringe IBO middleweight title but won’t be defending it against the smaller welterweight Benn (23-0, 14 KOs) on Saturday, April 26, at Tottenham Hotspur Stadium in London. DAZN will stream the Matchroom Boxing card.

This is about family pride.

The parents of Eubank and Benn actually began the feud in the 1990s.

Papa Nigel Benn fought Papa Chris Eubank twice. Losing as a middleweight in November 1990 at Birmingham, England, then fighting to a draw as a super middleweight in October 1993 in Manchester. Both were world title fights.

Eubank was undefeated and won the WBO middleweight world title in 1990 against Nigel Benn by knockout. He defended it three times before moving up and winning the vacant WBO super middleweight title in September 1991. He defended the super middleweight title 14 times before suffering his first pro defeat in March 1995 against Steve Collins.

Benn won the WBO middleweight title in April 1990 against Doug DeWitt and defended it once before losing to Eubank in November 1990. He moved up in weight and took the WBC super middleweight title from Mauro Galvano in Italy by technical knockout in October 1992. He defended the title nine times until losing in March 1996. His last fight was in November 1996, a loss to Steve Collins.

Animosity between the two families continues this weekend in the boxing ring.

Conor Benn, the son of Nigel, has fought mostly as a welterweight but lately has participated in the super welterweight division. He is several inches shorter in height than Eubank but has power and speed. Kind of a British version of Gervonta “Tank” Davis.

“It’s always personal, every opponent I fight is personal. People want to say it’s strictly business, but it’s never business. If someone is trying to put their hands on me, trying to render me unconscious, it’s never business,” said Benn.

This fight was scheduled twice before and cut short twice due to failed PED tests by Benn. The weight limit agreed upon is 160 pounds.

Eubank, a natural middleweight, has exchanged taunts with Benn for years. He recently avenged a loss to Liam Smith with a knockout victory in September 2023.

“This fight isn’t about size or weight. It’s about skill. It’s about dedication. It’s about expertise and all those areas in which I excel in,” said Eubank. “I have many, many more years of experience over Conor Benn, and that will be the deciding factor of the night.”

Because this fight was postponed twice, the animosity between the two feuding fighters has increased the attention of their fans. Both fighters are anxious to flatten each other.

“He’s another opponent in my way trying to crush my dreams. trying to take food off my plate and trying to render me unconscious. That’s how I look at him,” said Benn.

Eubank smiles.

“Whether it’s boxing, whether it’s a gun fight. Defense, offense, foot movement, speed, power. I am the superior boxer in each of those departments and so many more – which is why I’m so confident,” he said.

Supporting Bout

Former world champion Liam Smith (33-4-1, 20 KOs) tangles with Ireland’s Aaron McKenna (19-0, 10 KOs) in a middleweight fight set for 12 rounds on the Benn-Eubank undercard in London.

“Beefy” Smith has long been known as one of the fighting Smith brothers and recently lost to Eubank a year and a half ago. It was only the second time in 38 bouts he had been stopped. Saul “Canelo” Alvarez did it several years ago.

McKenna is a familiar name in Southern California. The Irish fighter fought numerous times on Golden Boy Promotion cards between 2017 and 2019 before returning to the United Kingdom and his assault on continuing the middleweight division. This is a big step for the tall Irish fighter.

It’s youth versus experience.

“I’ve been calling for big fights like this for the last two or three years, and it’s a fight I’m really excited for. I plan to make the most of it and make a statement win on Saturday night,” said McKenna, one of two fighting brothers.

Monster in L.A.

Japan’s super star Naoya “Monster” Inoue arrived in Los Angeles for last day workouts before his Las Vegas showdown against Ramon Cardenas on Sunday May 4, at T-Mobile Arena. ESPN will televise and stream the Top Rank card.

It’s been four years since the super bantamweight world champion performed in the US and during that time Naoya (29-0, 26 KOs) gathered world titles in different weight divisions. The Japanese slugger has also gained fame as perhaps the best fighter on the planet. Cardenas is 26-1 with 14 KOs.

Pomona Fights

Super featherweights Mathias Radcliffe (9-0-1) and Ezequiel Flores (6-4) lead a boxing card called “DMG Night of Champions” on Saturday April 26, at the historic Fox Theater in downtown Pomona, Calif.

Michaela Bracamontes (11-2-1) and Jesus Torres Beltran (8-4-1) will be fighting for a regional WBC super featherweight title. More than eight bouts are scheduled.

Doors open at 6 p.m. For ticket information go to: www.tix.com/dmgnightofchampions

Fights to Watch

Sat. DAZN 9 a.m. Conor Benn (23-0) vs Chris Eubank Jr. (34-3); Liam Smith (33-4-1) vs Aaron McKenna (19-0).

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

Featured Articles

Floyd Mayweather has Another Phenom and his name is Curmel Moton

Floyd Mayweather has Another Phenom and his name is Curmel Moton

In any endeavor, the defining feature of a phenom is his youth. Philadelphia Phillies outfielder Bryce Harper was a phenom. He was on the radar screen of baseball’s most powerful player agents when he was 14 years old.

Curmel Moton, who turns 19 in June, is a phenom. Of all the young boxing stars out there, wrote James Slater in July of last year, “Curmel Moton is the one to get most excited about.”

Moton was born in Salt Lake City, Utah. His father Curtis Moton, a barber by trade, was a big boxing fan and specifically a big fan of Floyd Mayweather Jr. When Curmel was six, Curtis packed up his wife (Curmel’s stepmom) and his son and moved to Las Vegas. Curtis wanted his son to get involved in boxing and there was no better place to develop one’s latent talents than in Las Vegas where many of the sport’s top practitioners came to train.

Many father-son relationships have been ruined, or at least frayed, by a father’s unrealistic expectations for his son, but when it came to boxing, the boy was a natural and he felt right at home in the gym.

The gym the Motons patronized was the Mayweather Boxing Club. Curtis took his son there in hopes of catching the eye of the proprietor. “Floyd would occasionally drop by the gym and I was there so often that he came to recognize me,” says Curmel. What he fails to add is that the trainers there had Floyd’s ear. “This kid is special,” they told him.

It costs a great deal of money for a kid to travel around the country competing in a slew of amateur boxing tournaments. Only a few have the luxury of a sponsor. For the vast majority, fund raisers such as car washes keep the wheels greased.

Floyd Mayweather stepped in with the financial backing needed for the Motons to canvas the country in tournaments. As an amateur, Curmel was — take your pick — 156-7 or 144-6 or 61-3 (the latter figure from boxrec). Regardless, at virtually every tournament at which he appeared, Curmel Moton was the cock of the walk.

Before the pandemic, Floyd Mayweather Jr had a stable of boxers he promoted under the banner of “The Money Team.” In talking about his boxers, Floyd was understated with one glaring exception – Gervonta “Tank” Davis, now one of boxing’s top earners.

When Floyd took to praising Curmel Moton with the same effusive language, folks stood up and took notice.

Curmel made his pro debut on Sept. 30, 2023, at the T-Mobile Arena in Las Vegas on the undercard of the super middleweight title fight between Canelo Alvarez and Jermell Charlo. After stopping his opponent in the opening round, he addressed a flock of reporters in the media room with Floyd standing at his side. “I felt ready,” he said, “I knew I had Floyd behind me. He believes in me. I had the utmost confidence going into the fight. And I went in there and did what I do.”

Floyd ventured the opinion that Curmel was already a better fighter than Leigh Wood, the reigning WBA world featherweight champion who would successfully defend his belt the following week.

Moton’s boxing style has been described as a blend of Floyd Mayweather and Tank Davis. “I grew up watching Floyd, so it’s natural I have some similarities to him,” says Curmel who sparred with Tank in late November of 2021 as Davis was preparing for his match with Isaac “Pitbull” Cruz. Curmell says he did okay. He was then 15 years old and still in school; he dropped out as soon as he reached the age of 16.

Curmel is now 7-0 with six KOs, four coming in the opening round. He pitched an 8-round shutout the only time he was taken the distance. It’s not yet official, but he returns to the ring on May 31 at Mandalay Bay in Las Vegas where Caleb Plant and Jermall Charlo are co-featured in matches conceived as tune-ups for a fall showdown. The fight card will reportedly be free for Amazon Prime Video subscribers.

Curmel’s presumptive opponent is Renny Viamonte, a 28-year-old Las Vegas-based Cuban with a 4-1-1 (2) record. It will be Curmel’s first professional fight with Kofi Jantuah the chief voice in his corner. A two-time world title challenger who began his career in his native Ghana, the 50-year-old Jantuah has worked almost exclusively with amateurs, a recent exception being Mikaela Mayer.

It would seem that the phenom needs a tougher opponent than Viamonte at this stage of his career. However, the match is intriguing in one regard. Viamonte is lanky. Listed at 5-foot-11, he will have a seven-inch height advantage.

Keeping his weight down has already been problematic for Moton. He tipped the scales at 128 ½ for his most recent fight. His May 31 bout, he says, will be contested at 135 and down the road it’s reasonable to think he will blossom into a welterweight. And with each bump up in weight, his short stature will theoretically be more of a handicap.

For fun, we asked Moton to name the top fighter on his pound-for-pound list. “[Oleksandr] Usyk is number one right now,” he said without hesitation,” great footwork, but guys like Canelo, Crawford, Inoue, and Bivol are right there.”

It’s notable that there isn’t a young gun on that list. Usyk is 38, a year older than Crawford; Inoue is the pup at age 32.

Moton anticipates that his name will appear on pound-for-pound lists within the next two or three years. True, history is replete with examples of phenoms who flamed out early, but we wouldn’t bet against it.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

Featured Articles

Arne’s Almanac: The First Boxing Writers Assoc. of America Dinner Was Quite the Shindig

The first annual dinner of the Boxing Writers Association of America was staged on April 25, 1926 in the grand ballroom of New York’s Hotel Astor, an edifice that rivaled the original Waldorf Astoria as the swankiest hotel in the city. Back then, the organization was known as the Boxing Writers Association of Greater New York.

The ballroom was configured to hold 1200 for the banquet which was reportedly oversubscribed. Among those listed as agreeing to attend were the governors of six states (New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Connecticut, and Maryland) and the mayors of 10 of America’s largest cities.

In 1926, radio was in its infancy and the digital age was decades away (and inconceivable). So, every journalist who regularly covered boxing was a newspaper and/or magazine writer, editor, or cartoonist. And at this juncture in American history, there were plenty of outlets for someone who wanted to pursue a career as a sportswriter and had the requisite skills to get hired.

The following papers were represented at the inaugural boxing writers’ dinner:

New York Times

New York News

New York World

New York Sun

New York Journal

New York Post

New York Mirror

New York Telegram

New York Graphic

New York Herald Tribune

Brooklyn Eagle

Brooklyn Times

Brooklyn Standard Union

Brooklyn Citizen

Bronx Home News

This isn’t a complete list because a few of these papers, notably the New York World and the New York Journal, had strong afternoon editions that functioned as independent papers. Plus, scribes from both big national wire services (Associated Press and UPI) attended the banquet and there were undoubtedly a smattering of scribes from papers in New Jersey and Connecticut.

Back then, the event’s organizer Nat Fleischer, sports editor of the New York Telegram and the driving force behind The Ring magazine, had little choice but to limit the journalistic component of the gathering to writers in the New York metropolitan area. There wasn’t a ballroom big enough to accommodate a good-sized response if he had extended the welcome to every boxing writer in North America.

The keynote speaker at the inaugural dinner was New York’s charismatic Jazz Age mayor James J. “Jimmy” Walker, architect of the transformative Walker Law of 1920 which ushered in a new era of boxing in the Empire State with a template that would guide reformers in many other jurisdictions.

Prizefighting was then associated with hooligans. In his speech, Mayor Walker promised to rid the sport of their ilk. “Boxing, as you know, is closest to my heart,” said hizzoner. “So I tell you the police force is behind you against those who would besmirch or injure boxing. Rowdyism doesn’t belong in this town or in your game.” (In 1945, Walker would be the recipient of the Edward J. Neil Memorial Award given for meritorious service to the sport. The oldest of the BWAA awards, the previous recipients were all active or former boxers. The award, no longer issued under that title, was named for an Associated Press sportswriter and war correspondent who died from shrapnel wounds covering the Spanish Civil War.)

Another speaker was well-traveled sportswriter Wilbur Wood, then affiliated with the Brooklyn Citizen. He told the assembly that the aim of the organization was two-fold: to help defend the game against its detractors and to promote harmony among the various factions.

Of course, the 1926 dinner wouldn’t have been as well-attended without the entertainment. According to press dispatches, Broadway stars and performers from some of the city’s top nightclubs would be there to regale the attendees. Among the names bandied about were vaudeville superstars Sophie Tucker and Jimmy Durante, the latter of whom would appear with his trio, Durante, (Lou) Clayton, and (Eddie) Jackson.

There was a contraction of New York newspapers during the Great Depression. Although empirical evidence is lacking, the inaugural boxing writers dinner was likely the largest of its kind. Fifteen years later, in 1941, the event drew “more than 200” according to a news report. There was no mention of entertainment.

In 1950, for the first time, the annual dinner was opened to the public. For $25, a civilian could get a meal and mingle with some of his favorite fighters. Sugar Ray Robinson was the Edward J. Neil Award winner that year, honored for his ring exploits and for donating his purse from the Charlie Fusari fight to the Damon Runyon Cancer Fund.

There was no formal announcement when the Boxing Writers Association of Greater New York was re-christened the Boxing Writers Association of America, but by the late 1940s reporters were referencing the annual event as simply the boxing writers dinner. By then, it had become traditional to hold the annual affair in January, a practice discontinued after 1971.

The winnowing of New York’s newspaper herd plus competing banquets in other parts of the country forced Nat Fleischer’s baby to adapt. And more adaptations will be necessary in the immediate future as the future of the BWAA, as it currently exists, is threatened by new technologies. If the forthcoming BWAA dinner (April 30 at the Edison Ballroom in mid-Manhattan) were restricted to wordsmiths from the traditional print media, the gathering would be too small to cover the nut and the congregants would be drawn disproportionately from the geriatric class.

Some of those adaptations have already started. Last year, Las Vegas resident Sean Zittel, a recent UNLV graduate, had the distinction of becoming the first videographer welcomed into the BWAA. With more and more people getting their news from sound bites, rather than the written word, the videographer serves an important function.

The reporters who conducted interviews with pen and paper have gone the way of the dodo bird and that isn’t necessarily a bad thing. A taped interview for a “talkie” has more integrity than a story culled from a paper and pen interview because it is unfiltered. Many years ago, some reporters, after interviewing the great Joe Louis, put words in his mouth that made him seem like a dullard, words consistent with the Sambo stereotype. In other instances, the language of some athletes was reconstructed to the point where the reader would think the athlete had a second job as an English professor.

The content created by videographers is free from that bias. More of them will inevitably join the BWAA and similar organizations in the future.

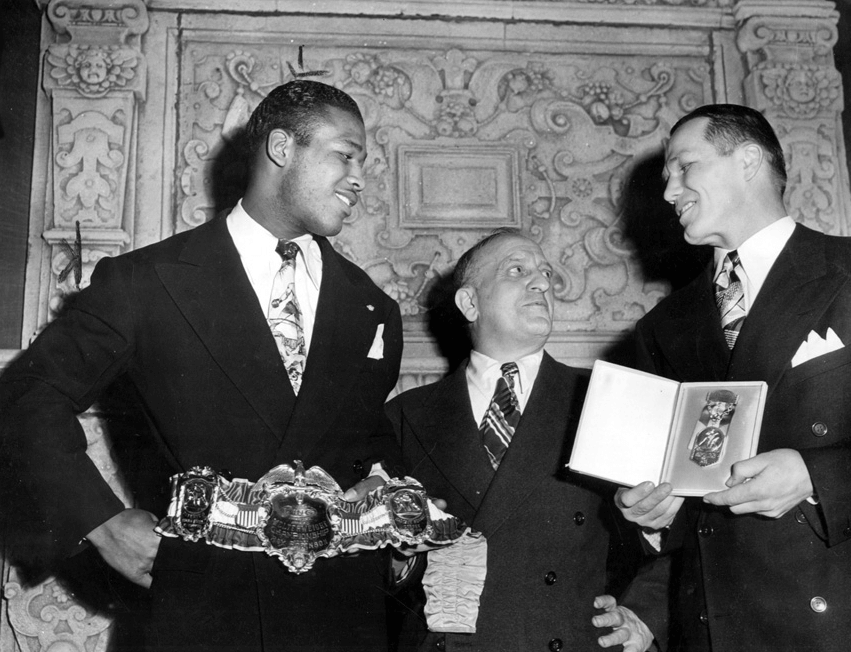

Photo: Nat Fleischer is flanked by Sugar Ray Robinson and Tony Zale at the 1947 boxing writers dinner.

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 319: Rematches in Las Vegas, Cancun and More

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRingside at the Fontainebleau where Mikaela Mayer Won her Rematch with Sandy Ryan

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoWilliam Zepeda Edges Past Tevin Farmer in Cancun; Improves to 34-0

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoHistory has Shortchanged Freddie Dawson, One of the Best Boxers of his Era

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 320: Women’s Boxing Hall of Fame, Heavyweights and More

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoResults and Recaps from Las Vegas where Richard Torrez Jr Mauled Guido Vianello

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoFilip Hrgovic Defeats Joe Joyce in Manchester

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoWeekend Recap and More with the Accent of Heavyweights