Canada and USA

Steve “U.S.S.” Cunningham: From Carriers Back to Cruisers

They say that what goes around often comes around. That is probably as true for sailors as anyone else, and maybe more so for a former bosun’s mate-turned-boxer, Steve “USS” Cunningham, than for anyone who ever prepared himself for battle on the sea or in the ring.

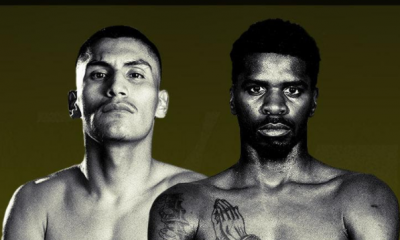

When the 39-year-old Cunningham (28-7-1, 13 KOs), a former two-time IBF cruiserweight champion, challenges 10-years-younger WBO cruiser titlist Krzysztof Glowacki (25-0, 16 KOs) Saturday night at the Barclays Center in Brooklyn, N.Y., it will mark the figurative completion of a remarkable and circuitous professional journey that can be framed in nautical as well as pugilistic terms. A man who served his country aboard the aircraft carriers America and Enterprise from 1994 to ’98, the 6-foot-3 native of Philadelphia took up boxing while stationed at the Norfolk (Va.) Naval Station, progressing rapidly enough to win the 1998 National Golden Gloves title at 178 pounds while still in the Navy.

Check out The Sweet Science article “Barclays Center Quick Results – PBC on NBC”.

After mustering out of the military, Cunningham turned pro as a very lean, 182-pound cruiserweight on Oct. 28, 2000, with a four-round split decision over Norman Jones in Savannah, Ga. The terminology to differentiate the weight classes of his new occupation is significant; after working on the largest warships ever constructed, with Nimitz Class carriers averaging 1,040 feet in length and with crews of 6,000, he was boxing as a cruiser, a designation for smaller, more maneuverable vessels that have been integral parts of the American Navy’s fleet since the late 1700s. Modern-day Ticonderoga Class cruisers average 567 feet, with crews of 300.

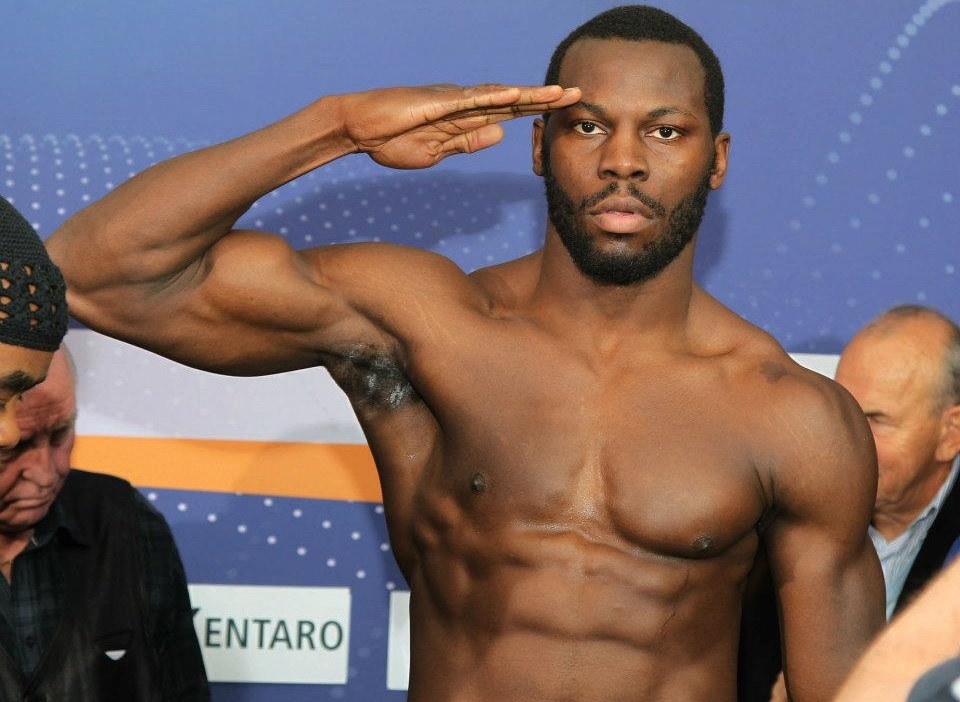

But Cunningham – a workout warrior with an exceptionally high metabolism and washboard abs that would impress a Calvin Klein underwear model – made the decision to move up to heavyweight in 2012, despite his body’s natural resistance to adding enough heft to reasonably justify such a career change. He was a taut 207 pounds for his heavyweight debut, a 10-round unanimous decision over Jason Govern, who outweighed him by 32 pounds.

The symbolism of Cunningham’s 3½-year foray into the heavyweight division is inescapable. In eight fights against boxing’s really big boys, he was outweighed in each instance, by a whopping 73 pounds against Natu Visnia (whom Cunningham stopped in seven rounds) and by 44 pounds when he attempted to scale a 6-foot-9 mountain named Tyson Fury. Although Cunningham surprised the future lineal heavyweight champion by flooring him in the second round, he admits to being worn down by “wrestling and rumbling” with the hulking Briton, and was knocked out in the seventh round by a punch he said he didn’t see because his line of vision was blocked by Fury’s massive forearm.

Despite being outweighed by an average of 28¼ pounds, Cunningham was 4-3-1 as a heavyweight and might even have entered the conversation as a possible challenger to another giant, Wladimir Klitschko, whom Fury eventually dethroned, had he won the David-vs.-Goliath matchup that Cunningham’s savvy trainer, Naazim Richardson, didn’t want him to take in the first place.

“Steve fighting as a heavyweight was ridiculous, and I told him that,” Richardson said. “Some fighters, you have to protect them from themselves. It was like that when I had Shane Mosley and he fought Canelo (Alvarez). But I needed to be there in order to protect Shane. I had the same feeling when Steve moved up to heavyweight. His heart is immense, sometimes too immense for his own good. I’ve never encountered a fighter with the kind of heart Steve Cunningham has. Never.”

Perhaps it was a mission doomed to disappointment, the little cruiser mixing it up with the massive carriers, but Cunningham figures to be in somewhat less treacherous waters against Glowacki, the Polish southpaw who, in his U.S. debut, won his title by registering an action-packed 11th-round knockout of long-reigning Marco Huck, of Germany, last Aug. 14 at the Prudential Center in Newark, N.J., on the undercard of a show headlined by Cunningham’s draw with Antonio Tarver.

“It should be a little more comfortable,” Cunningham said of a bout against an opponent of more or less the same physical dimensions. “This guy shouldn’t be able to bully me around if we get tangled up in a clinch. We’re about the same size. I fought all those heavyweights pretty much as a cruiserweight anyway. I thought I could get up to 215 or 220, but the most I weighed for any fight was 210 against Fury, and that was only by drinking a gallon of milk before the weigh-in. I usually came in at 203, 204, something like that.

“The main thing I had going for me was my heart. It isn’t always about how big you are. Anybody can be beat. Godzilla can be beat, if you come up with the right game plan. Smaller heavyweights have had success. David Haye did. Evander Holyfield did. I thought, `I want to be like those guys.’”

Cunningham’s most notable victory as a heavyweight came on April 4, 2014, when he overcame two fifth-round knockdowns to outpoint the previously undefeated Amir Mansour in 10 rounds on April 4, 2014, at the Liacouras Center in Philly. The biggest risk, and one he felt he needed to take, came against Fury, a 4-1 favorite, on April 20, 2013, at The Theater at Madison Square Garden. Cunningham had dropped a hotly disputed 12-round split decision in his rematch with Poland’s Tomasz Adamek on Dec. 22, 2012, in Bethlehem, Pa., and he figured that the only way to make up lost ground was to make the biggest splash possible, and who better to do that against than against a the carrier-sized Fury?

“My thinking was that if I could beat someone that big, it would prove to everybody that I was a legitimate heavyweight, and I deserved the opportunity to fight Wladimir,” Cunningham said. “It might have happened, too, had I beaten Fury. But you can talk about the `what-ifs’ all day. Boxing is like gambling. Sometimes you just have to roll the dice.”

One school of thought is that Cunningham and his manager-wife, Livvy, looked at the heavyweight division, with its greater prestige and presumably larger purses, as a means of securing more financial assistance for their young daughter, Kennedy, who was born with hypoplastic left heart syndrome, which basically means that the left side of her heart did not fully develop. And there is some truth to that; Kennedy, now 10, underwent a successful heart-transplant operation on Dec. 5, 2014. Dubbed the “miracle child,” she’s now a happy, healthy little girl with the expectation of a full life that once seemed in doubt.

Another theory is that Cunningham, just one weight class below heavyweight, couldn’t help but dream of capturing what once was the most prestigious title in all of sports. Being a cruiserweight champion is very nice, but it is not the same as being able to say you’ve joined an exclusive club whose membership includes such legends of the sport as Jack Johnson, Jack Dempsey, Joe Louis, Rocky Marciano, Muhammad Ali, Joe Frazier, George Foreman, Mike Tyson and Holyfield. There is also some truth to that line of reasoning.

But Cunningham said his motivation was spurred in part by what he believed to be real or imagined bias against him in the first phase of his cruiserweight incarnation. He says he was not a priority of his first promoter, Don King, who regularly had him take title fights in the other guy’s home country, the result being several losses on points that he felt could have and should have gone the other way.

Nor did he think much had changed when he signed on with Main Events, whose stable was headed up by Adamek, the Polish national hero who was regularly drawing sellout crowds in the Prudential Center, which had become his home-away-from-home. Another close loss to Adamek, this time at heavyweight, was enough to spur Steve and Livvy to again consider their promotional options.

“If the judges can’t judge better than that, they shouldn’t even be allowed to judge two roaches running up a wall,” a miffed Cunningham said after the rematch loss to Adamek he believes he clearly deserved to win.

Now one of 200 fighters under the large Premier Boxing Champions tent overseen by the shadowy Al Haymon, Cunningham will be bidding for his third cruiser championship in his first bout in his old weight class since the second of his back-to-back defeats against Yoan Pablo Hernandez on Feb. 4, 2012. Make of that what you will. But, even given his remarkable fitness level and Haymon’s influence, Cunningham understands that the Glowacki bout, which will be nationally televised via NBC, might represent the last hurrah for a 39-year-old guy whose boxing odometer has added lots more miles after those eight heavyweight wars.

“I’m thinking I better win this one,” Cunningham said. “I was thinking I’d better win the Mansour fight. I’d better win the Fury fight. You never want to lose, but if you do, you hope you at least look good. There is such a thing as a `good’ loss, when you put on an entertaining enough performance that the fans want to see you again. But, realistically, I really can’t afford another setback at this stage.”

If there is one thing that’s certain about Cunningham, it’s that he’ll never be asked to do one of those weight-loss commercials where slimmed-down clients speak about taking off 40 or 50 pounds of unwanted paunch thanks to some innovative diet plan or newly marketed exercise equipment. Richardson said he accompanied Cunningham to New Orleans to meet with fitness guru Mackie Shilstone, who helped boxing greats Michael Spinks and Roy Jones Jr. add weight the proper way for their successful sojourns into the heavyweight division. The idea was that Shilstone could work the same sort of wonders with Cunningham. But Shilstone and Cunningham came to quickly realize that no program was going to turn this particular cruiser into a real carrier.

“Mackie gave us some suggestions about exercises and dietary stuff that might help Steve put some weight on, but Steve’s metabolism is such that it comes right back off again,” Richardson said. “He’d get up to 205 or 206 and that’s about as high as he could go. I know they say he was 210 for the Fury fight, but I never saw Steve at 210. What I told him was to forget about trying to put all that weight on and to just keep his skills sharp. So those heavyweights are always going to be bigger than you? Don’t worry about it. Out-skill them.

“The thing with Steve is that he’s always in boxing-shape. He works out three, four times a week in the gym even between fights. He takes his sons (Steve Jr., 13, and Cruz, 11) to the gym to work out with him and he goes to the pool and swims laps. A lot of laps.”

Wouldn’t you expect a former sailor to feel at home in the water?

Check out The Boxing Channel video “PBC on NBC Results – Spence Jr Stops Algieri in 5”.

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Book Review5 days ago

Book Review5 days agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoOleksandr Usyk Continues to Amaze; KOs Daniel Dubois in 5 One-Sided Rounds