Canada and USA

BIG BAD BOB

BIG BAD BOB – Back when America got up early to get ahead and men were men, “going west” put hair on your chest. The unforgiving sun, the desolate expanse, the chance to mix it up with others who painted their faces where you rolled up your sleeves — going west in the nineteenth century was akin to joining the service in the twentieth.

In the twenty-first, young Americans tend to stay home. They shy away from mixing it up lest they get hurt, or sued. Those who do leave home go to universities where old-school values are under constant attack and an aging cult of Haight-Ashbury types preach the soft new faith of fops. The adventurous paint their faces, albeit for different reasons, and go west to Hollywood, the faith’s fount of public enlightenment and propaganda.

Not everyone has acquiesced. From the first flicker in the first movie house there have been leading men who cringe at the fopification of their image. Rudolph Valentino cherished his friendship with Jack Dempsey precisely because of his alienation from red-blooded Americans who spurned him while their girlfriends swooned. An immigrant, Valentino’s offense was perfectly pomaded hair, mastery of the Tango, and the jewelry he wore in true Italian fashion. In July 1926, the Chicago Tribune published an editorial lamenting the installation of pink powder puff machines in men’s washrooms and blaming that and other great societal ills on Valentino. “Homo Americanus! Why didn’t someone quietly drown Rudolph Guglielmo, alias Valentino, years ago?” it said. “Hollywood is the national school of masculinity. Rudy, the beautiful gardener’s boy, is the prototype of the American male… oh, sugar!”

Valentino, deeply offended, rolled up his sleeves and publicly challenged the unnamed editor to join him in a boxing ring so that he “may snap a real fist” at the editor’s “sagging jaw” and teach him “to respect a man even though he happens to prefer to keep his face clean.” The star promised to be in Chicago within ten days and signed off “with Utter Contempt.” The letter, and the challenge, went ignored. Within weeks, Valentino was stricken with gastric ulcers that required emergency surgery. As the anesthetic wore off, Valentino, at death’s door, looked hazily at the doctor and said, “Doctor, am I a pink puff?”

Others gaze upon their own flickering image and are instantly fopified and often fooled. They get ideas that their silk pajamas somehow fail to impede. In 1934, the third husband of wealthy socialite Madeline Astor was a Hollywood dandy whose boxing career ended at the gnarled hands of Les Kennedy, the “Long Beach Longshoreman.” Kennedy, whom the UP tells us, “lay claim to no social standing whatever” stood up to Mr. Madeline Astor’s punches as if they were, well, pink powder puffs, and then landed an uppercut in the fourth round that fizzled all the fun for the “galaxy of cinema notables” seated at ringside. Their collective gaze dropped to the canvas with the millionaire and there remained for ten seconds plus.

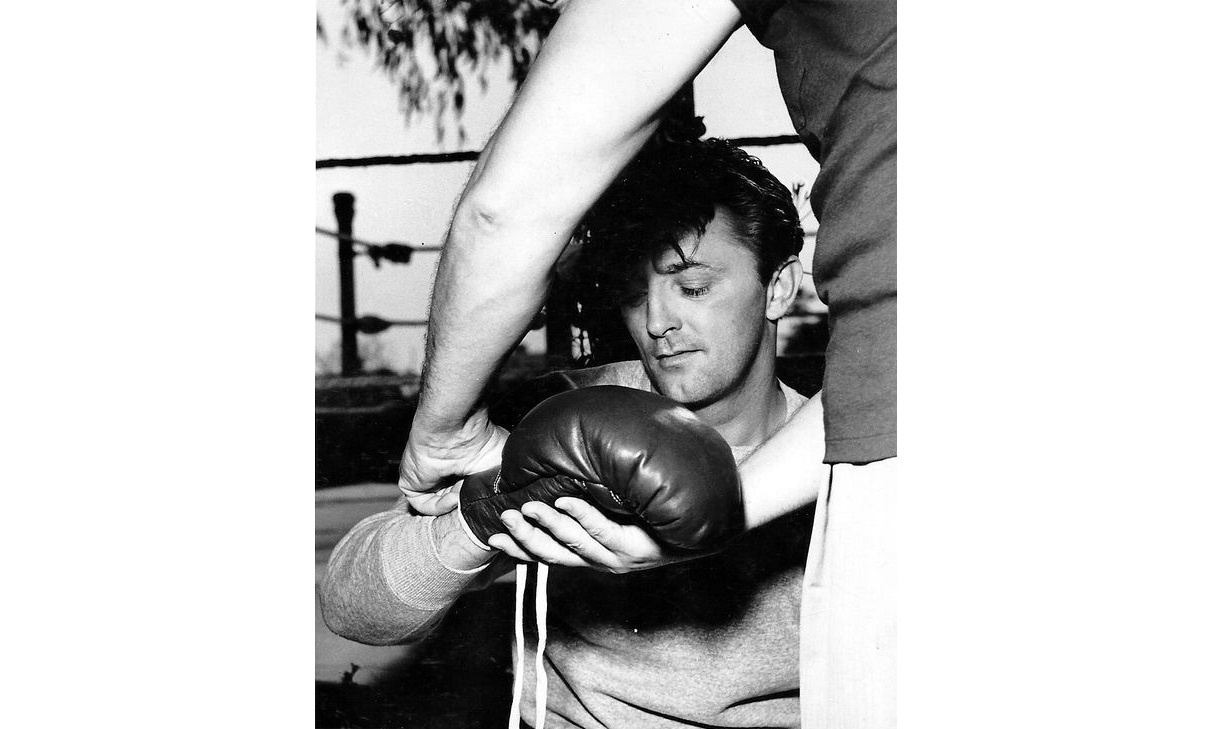

Eighteen miles south of Legion Stadium, a young Robert Mitchum roused himself in a box car rumbling toward the Alameda Street train yards and ambled over to the sliding door. He stood framed as the ground raced beneath him, his arms stretching out from shoulders that would fill film frames a few years hence, and jumped off. Mentored by older hobos, he found a storefront mission for a meal and a flop house for a snooze. He earned quick money on the semipro circuit in out-of-the-way places like Redding, California and Sparks, Nevada. “I used to be what they called a bum fighter,” he said. “If someone doesn’t show up, you’ve got a job.” He guessed he’d had about seventeen fights for twenty-five dollar purses until a fighter with arms like Sam Langford sent his nose across his cheek. Mitchum never named him, but the memory of his mayhem was in the morning mirror.

The future star of screen gems like Out of the Past (1947), The Night of the Hunter (1955), Cape Fear (1962), and The Friends of Eddie Coyle (1973) emerged from the Depression’s drifting classes and became, at different times a ditchdigger, longshoreman, playwright, sheet metal worker, shoe salesman, and writer for a raunchy nightclub act and an astrologer (the latter until the butler caught him in the act of stealing a case of booze). During World War II he was a “rectal inspector.”

“In a fit of embarrassed desperation I became a movie actress,” he said. And what an actress he was — he specialized in playing cowboys and soldiers and was film noir’s most convincing anti-hero. “I’ve got a baritone voice, a broken nose, stand six feet high and can change a tire without using a stand-in. Hell, I look like I’ve changed five million tires.” That, he told the Los Angeles Free Press, explained his enduring popularity to red-blooded Americans: “Men say, ‘that bum’s just a goddamn mechanic. If he can get to be a movie star, I can be king.’”

Hollywood fops didn’t know what to make of him; it was as if someone shipped in a gorilla and turned it loose. He once destroyed a set on an RKO lot and was rumored to have destroyed a good many more. He hung an annoying producer upside down on a lamppost. A director demanding take after take of a scene where actress Jean Simmons is slapped was slapped himself. “Once more?” Mitchum said after the director’s head finished rotating. Warned by a stuntman that fellow ex-pug and actor Jack Palance threw real punches in fight scenes while filming Second Chance, Mitchum ducked under one of them “and caught him in the gut, because I knew he had a weak gizzard.” Palance, he said, “puked over my shoulder.” Biographer Lee Server tells us that at fifty-three he was taking swings at a director who refused to let him change the script during the final week of shooting Going Home.

He was worse during off hours. In 1948, he was arrested at a party, stuck with the dubious charge of “conspiring to possess marijuana,” and sentenced to sixty days in county jail. When asked by the judge what his occupation was, he replied, “ex-actor.” But the pinch only contributed to his reputation. Stories abound of car chases with cops, women tearing off their tops to win his attentions, drunken rampages, and fist-fighting with no regard whatsoever for the Queensberry rules. Here we find him in a bar in Tobago where he flattened three U.S. sailors on shore leave; there we find him crashing a social event looking for Charles Bronson who had said his tough-guy persona was just for show. (Bronson reportedly fled.)

His reputation went Rushmore in November 1951 after the Colorado Springs Gazette ran a headline that said “Camp Carson Soldier Injured in Ruckus with Mitchum.” Mitchum was at the Red Fox bar in the Alamo Hotel during filming of One Minute to Zero. He claimed that the soldier had backhanded a colonel and shoved a major during a ruckus. “I said, ‘Man, you’re in trouble.’ He said, ‘I’m in trouble?’ and cocked his right hand back.” Mitchum slipped the punch and the soldier’s fist hit the wall. “I had hold of him all the time, digging in,” he said. When five grabbed him to break it up, the soldier let fly a hook. Mitchum leaned back, got an arm loose, and knocked him down. And he wasn’t finished yet.

The soldier’s name was Bernie Reynolds. Bernie Reynolds was a heavyweight rated in the top-ten by The Ring only two years earlier. His record stood at 50-9-1 with 30 knockouts.

A military police officer said the two of them were scuffling and fell into the lounge where Mitchum had the fighter draped over a divan and was slamming his head on the edge of a table. “[Mitchum] hit me on the back of the head and I fell to the floor,” said Reynolds. “After that I don’t remember too much except that he was kicking me about the head several times. I woke up at the hospital.” In an era where only the Rockettes could get away with kicking, Mitchum’s manliness was called into question. For perhaps the only time in his life, he got defensive — denying that he used his feet despite the fact that several witnesses said he did. Years later, he shrugged his shoulders at that as he did at everything else. “It wasn’t the Marquis of Queensberry rules,” he told People. “I brushed my foot against his head to say ‘See, asshole, you see what I could do to you?”

The kicking incident made national news and Mitchum released a statement. “An actor is always a target for the belligerent type of guy who thinks he is tough and movie he-men are softies [read: fops],” it said. “I never start a fight but I can assure you I can always finish one.”

—Almost always. There was a certain world-class welterweight who finished Mitchum as easily as Mitchum finished Reynolds. He too was something of an itinerant who had migrated west for the chance to mix it up. According to Them Ornery Mitchum Boys, his brother’s tell-all book, Mitchum sparred with him. The welterweight countered one of his flickering jabs, probably the first one, with a right hook to the flank. Mitchum never saw it coming. He felt it though, “a terrible burning” in his side.

As his mouth hung open and he gasped for breath, Charley Burley whispered in his ear: “That’s the name of the game, baby.”

|

Springs Toledo is the author of The Gods of War (Tora, 2014) and In the Cheap Seats (Tora, 2016). |

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Book Review2 weeks ago

Book Review2 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles6 days ago

Featured Articles6 days agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRahaman Ali (1943-2025)

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoTop Rank Boxing is in Limbo, but that Hasn’t Benched Robert Garcia’s Up-and-Comers