Canada and USA

28 Years After His Greatest Moment of Glory, Iran Barkley Still Gets Props

Iran Barkley Still Gets Props – It has been said that there are two ways to win a football or basketball game. One is when your team scores more points than the guys wearing the different-colored jerseys; the other is to have the other team score fewer points than yours does. And while that might sound like the same thing, there are subtle differences. Much hinges on what is or isn’t emphasized in describing what went into producing the end result.

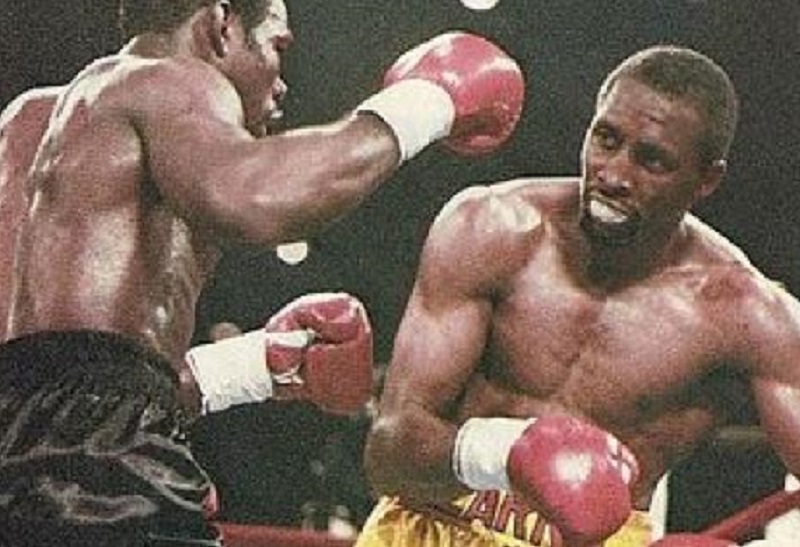

The same principle can be applied to boxing, where not all victories – or defeats – are created equal. Case in point: Iran “The Blade” Barkley’s bolt-from-the-blue, third-round technical knockout of heavily favored WBC middleweight champion Thomas Hearns on June 6, 1988, at the Las Vegas Hilton. Bleeding from cuts over both eyes and his mouth, Barkley seemed on the verge of possibly being stopped himself when he unfurled a wide right hand that caught Hearns flush on the jaw. Even as the discombobulated “Hitman” was in the process of collapsing onto his back with a thud, Barkley let fly another right that connected solidly. Although Hearns miraculously managed to beat the count, his eyes were glassy and his legs as limp as boiled spaghetti. The revitalized challenger surged forward and drove him with into the ropes with a volley of follow-up blows before referee Richard Steele did the right thing by stepping in and waving the bout off after an elapsed time of 2 minutes, 39 seconds.

“The two punches Iran threw before (the senses-separating knockdown shot) had no snap, no steam,” said veteran trainer Gil Clancy, one of the color analysts for the Showtime telecast. “Then, all of a sudden, there it was. Goes to show you that in boxing anything can happen.”

It should have been the greatest moment of what, on balance, turned out to be a very good professional career for Barkley, a reformed street tough from the South Bronx who would later win alphabet world championships as a super middleweight (IBF) and light heavyweight (WBA, ironically on a split decision over Hearns). But, almost predictably, the prevailing media narrative was not so much that Barkley had won, but rather that Hearns, the superstar, had lost.

The same scenario was played out yet again in Barkley’s next fight. In his first defense of his new title, Barkley took on the legendary Roberto Duran on Feb. 24, 1989, on a snowy night in Atlantic City. It was another barnburner – proclaimed 1989 Fight of the Year by The Ring magazine – but Duran, in no small part owing to his 11th-round knockdown of Barkley, won a split decision.

“And the story immediately became, `Duran is back!,’” said John Reetz, Barkley’s manager at the time and still his friend and benefactor. “If Iran had won, it would have been `Duran is finished!’”

But while being the “B” side in major fights can be frustrating and not as financially rewarding as for the more bankable guys with the big reputations, that isn’t to say there aren’t ample benefits to be reaped. Depending upon who’s doing the accounting, Barkley, now 56, earned somewhere between $3 million and $5 million from 1982 to ‘99. He was and still is a familiar presence on the boxing scene, especially in his hometown of New York City, where he continues to soak up adulation from fight fans who fondly remember what he did and how entertaining he was in doing it. He will attend the 91st annual Boxing Writers Association of America Awards Dinner on June 24 at the Copacabana in midtown Manhattan, where several people are sure to tell him they either were there in person or saw the telecast of the night when he put the hurt on Hearns.

“We walk around New York and people always give him props,” Reetz said. “Sure, he doesn’t have a pot to piss in, but it’s astounding that so many people still want to come up to him to shake his hand or to take a picture with him. He enjoys that, and why shouldn’t he? He’s a three-time world champion.”

Over the past 10 years or so, the tale of Iran Barkley has become less that of the never-say-die brawler who would march into hell wearing a gasoline overcoat than that of the riches-to-rags transient whose boxing fortune dissipated into a nightmare of homelessness, heartbreak and nights spent sleeping in the subway. That story – told so often about once-celebrated, now-destitute fighters whose skills at managing money proved nowhere as proficient as those they displayed inside the ropes – has been chronicled in recent years in publications ranging from the New York Times to The Wall Street Journal. Here is Iran Barkley, who had it all and threw it away with both hands. Readers are advised he is either to be pitied or rebuked for allowing himself to become another disposable commodity in a cruel sport that makes heroes on fight night and then leaves them flailing about on their own when the support system they had relied upon when times were good moves on.

Except that the familiar story, while containing elements of truth, doesn’t paint the entire picture of whom Iran Barkley is. Yes, in his youth he ran with a street gang called the Black Spades, but he has never served hard time or even been arrested. Yes, he sometimes has less-than-kind thoughts about his former promoter, Top Rank honcho Bob Arum, and the International Boxing Hall of Fame, which has had him as a guest for a number of induction weekends without adding him to its ranks of immortals, but he chooses not to dwell long on any perceived wrongs done unto him. The way Barkley looks at it, yesterday is gone and tomorrow holds the promise of better things, God willing.

“I don’t even think about it no more,” Barkley said, somewhat unconvincingly, when asked for his remembrances of the first tussle with Hearns. “It was a great moment for me to be sure, but people got their own opinions about that. Tommy was the one who was supposed to be super-great. Nobody gave me any chance to win. I get all that. But when I did win, all anybody wanted to talk about was Tommy losing. Even when I came back and beat him a second time (Barkley is the only fighter ever to have defeated Hearns twice), the talk still was about how I beat him the first time on a lucky punch.

“Yeah, right. Let me tell you something, there ain’t no luck in boxing. You either get your ass kicked, or you kick ass. I don’t make a big deal out of (the first Hearns fight) or the fact another anniversary of it is coming up. But I don’t want it to come off that I only have bad thoughts about boxing. I enjoy all the blessings that God gave me, and I look to Him for my strength and spiritual growth. I worked hard for everything I ever got, and I got a lot out of boxing.

“I lost a lot, too. But you know how it is. When you’re young you don’t know no better. I spent a lot and I messed up. I admit it. I wasn’t making anything near what (Sugar Ray) Leonard and Hearns were, but it was comfortable money. I just didn’t plan ahead like I should have.”

Some of the wounds Barkley inflicted upon himself, and some were brought about by happenstance. He bought a nice house in Nyack, N.Y., as well as a carwash and a condominium in New Jersey. But after beating Hearns again on March 20, 1992, the nest egg he thought he was building for himself and his four daughters was sucked dry by two divorces, several lawsuits and his fondness for casino games of chance.

Barkley has blamed Arum, who also promoted Hearns, for being visibly disappointed when Barkley upset the Detroit slugger, and for not then promoting him as a star on Hearns’ level. But if boxing economics tells us anything, it’s that beating The Man doesn’t necessarily make you The Man.

“He wasn’t a pay-per-view fighter like some other guys, and that’s something no promoter can do anything about,” Arum said. “He didn’t have a personality that could connect” with the public in the same manner as more popular members of the Top Rank stable.

Reetz has heard his friend rail about the injustice of it all, and he can commiserate, but only to a point. The way he looks at it, Arum is a businessman and it would have been better for Top Rank’s bottom line had Hearns beaten Barkley as he was supposed to.

But more lasting damage was done to Barkley with the loss to Duran, who supposedly was on the downhill side of a remarkable boxing life. Had “The Blade” notched back-to-back wins over future Hall of Famers Hearns and Duran, Reetz said, “I believe Iran’s career would have gone in a whole different direction. If he’d gotten that decision, I honestly believe he’d be in Canastota (as an inductee into the IBHOF) right now.”

Hall of Famers can go broke the same as anyone else, and if fellow New Yorker Mike Tyson can not only blow $300 million but somehow wind up $62 million in debt, Barkley’s financial woes must seem like the squandering of petty change. But the emptying of Barkley’s bank account may have been hastened by the emotional toll brought on by the death of his beloved mother, Georgia, in 1999 as well as those of several of his siblings and other family members. The youngest of Georgia’s eight children (four boys and four girls), Iran is the sole surviving son, along with three of his sisters. Stress has been cited as the precipitating factor in the minor stroke he suffered in October 2014.

Homeless no more, Barkley now has his own modest apartment in his old stomping grounds of the South Bronx – the Veterans Boxers Association Ring 10 assisted him in securing it, as well as navigating the bureaucracy of applying for public benefits – and he is leading a less desperate, if still tenuous existence. He works out almost daily at Gleason’s Gym in Brooklyn, where he said he is more than willing “to help anyone who comes through the door.” Although he still does not have a regular source of income, he does not envision becoming a full-time trainer because … well, he has another boxing dream that he is daring to believe will yet be realized.

He wants to fight Tommy Hearns again.

“Me and Tommy, we speak,” Barkley said of Hearns, who is 57 and hasn’t fought since 2006. “We say `Hi’ whenever we see each other. He said he’s still looking to fight me, and I tell him he had two chances to do beat me and he couldn’t. But why not do it again? We need each other. Let us make some real money and go about our business.”

It won’t happen, of course, and that is for the best, and especially for Barkley. “The Blade” is a good 75 pounds heavier than he was the night he stopped Hearns, his butcher knife turned to butter knife. He forever shall remain undefeated in his two-bout rivalry with Hearns, which won’t pay any existing bills but is always good for a trip down memory lane upon request.

“Just since January of this year, I bet I’ve seen Iran at a half-dozen boxing events,” said Randy Gordon, the former chairman of the New York State Athletic Commission who now hosts a boxing show on SiriusXM. “He just wants to be there. Everyone knows him and they treat him great. They say, `Hey, Champ, sit at my table.’ People really like him. He’s a fun guy and he’s got some great stories.”

The best of which is true.

Iran Barkley Still Gets Props

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Book Review2 weeks ago

Book Review2 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles3 days ago

Featured Articles3 days agoThe Hauser Report: Debunking Two Myths and Other Notes

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRahaman Ali (1943-2025)