Argentina

War in the Night Sky: Firpo vs. Dempsey and the Dawn of Boxing in Argentina

“O human race, born to fly upward, wherefore at a little wind dost thou so fall?”

Dante Alighieri, The Divine Comedy

They came from every corner of the sprawling, growing metropolis. Thousands of men in black suits and hats, populating the sidewalks and then the streets and then the lawns and the manicured garden patches in front of the majestic new building of the National Congress, until the rectangular confines of the French-style public square could not contain them. Only then did they spill out onto the adjacent streets, murmuring to each other and occasionally gazing at the stars.

They came to witness a confrontation, a clash of titans, two angry celestial bodies colliding in the September sky, two bright comets trying to outshine each other. And the men in black waited, hoping that the building, an unshakable fortified tower strong enough to host a bout between Heaven and Hell within its confines, would project upon them a beacon of hope, a guiding light to take them to the Promised Land they hoped to have reached the very minute they set foot on the very soil they were standing on.

The men in black were not gathered for a protest in front of a government building, and were not there to participate in a conspiracy or a revolution. When the right time came, they didn’t look towards the magnificent neoclassical Argentine Congress building. Instead, they looked the other way, towards a brand new towering structure named after a rich Italian merchant, the tallest building in all of South America at the time and a reinforced concrete-made allegory of one of the world’s defining literary works, as it became the host of the revelation of a historic moment destined to perhaps outlive even the building itself.

The men in black held their collective breath under the starry sky until the light went on. And then, all hell broke loose. Hats in the air, screams of joy, a celebration big enough to inspire an entire nation to achieve things they never thought possible was set in motion by the miracle of that shiny blue lamp, which shone from a 360 degree glass dome as bright as God’s annunciation would shine in the Southern sky.

But just like the building’s elevators, constantly negotiating their way between the Inferno below and the Paradise above and back and forth through Purgatory, the light changed its color, and with it, its message. And then tragedy struck.

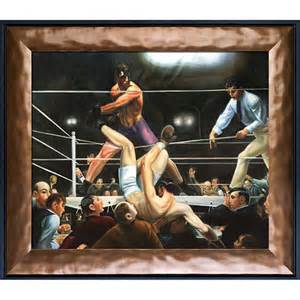

The blue light that shone at the top of the Barolo Palace on September 14th, 1923, was destined to announce the victory of a proud son of this southernmost country on Earth in his world championship fight. And it did shine its blue blessings upon the hopeful crowd below as soon as the announcement came all the way from the ringside at the Polo Grounds in New York that the great Jack Dempsey, the fearsome heavyweight champion, had fallen at the hands of Luis Angel Firpo, flying out of the ring in the very first round of the very first title bout by the very first Argentine to fight abroad in front of a hostile crowd.

But then, the light turned red. The confused and befuddled crowd stood in astonishment and silence as the 3000-watt lamp, bright enough to be seen on the other side of the widest river on the planet, changed its color to announce that indeed, once again, the underdog had fallen.

It would take until the next day, in which the newspapers would tell the entire story, for them to realize how close was Luis Angel Firpo, the “Wild Bull of the Pampas,” to achieving the impossible.

For seventeen seconds (give or take, depending on which account is to be believed), the great Jack Dempsey, “The Manassa Mauler” and reigning heavyweight champion of the world, had been out of the ring trying to regain his foothold and climb back into it to continue fighting.

For seventeen full seconds, a nation barely into its first century of life held the bragging rights of having its strongest and most fearsome son standing alone (literally) on a boxing ring, laying claim to the biggest prize in sports. For a fleeting moment, one of the largest gatherings of people in the history of Buenos Aires felt, through the magic of the airwaves conveyed through a series of lights projected from a building, the moment in which the pride of South America sent the mighty Dempsey down and out in demolishing fashion, with their bets and their pride flying out of the ring with Jack as well.

For those 17 seconds, they felt capable of anything and everything. And then reality set in.

They came dressed in black suits and ties. They came in rags, in peasant clothes and in greasy overalls, streaming endlessly from the bowels of ships arriving from almost every country in the world. The vast expanse of the South American plains, the ‘pampas’, embraced them with its promise of fertile lands of opportunity.

Most of them were men between the ages of 18 and 30, jobless and unskilled, looking for a place to call home and to form a family, without even imagining that there would be thousands of them in the same situation competing for the very same jobs and the few women that the country had to offer. Soon enough, they would give up their search for true love and become clients of one of the 6000 whorehouses that the city had to offer, in stark contrast with the less than 100 schools that catered to the very few children that were being born there at the time.

But the demographics were about to change even more in the coming years.

In 1890, Buenos Aires had a quarter of a million inhabitants. By 1910, they were two and a half million. And that was before WWI started spewing refugees and escapees to all corners of the planet, most of them traveling in empty cargo ships leaving Europe and the Middle East for the “breadbasket of the world”, as the country was known back then. Some of them, however, arrived in first-class cruise liners, hoping to turn their small savings into larger fortunes in the “land of silver.”

One of them was Luigi Barolo, an already wealthy Italian cotton merchant who was planning to make Argentina the new headquarter for his successful business.

And he did, amassing a significant wealth that allowed him, among other things, to build a grandiose tower bearing his name. But Barolo wouldn’t settle for just any building. He ordered the tallest and most modern building in the city, right across the street from the newly-built Congress, and a mere 20 blocks from the Government House. He ordered it made in reinforced concrete, and to have a 360-degree beacon of light shining from its top.

But the main feature of the building was not its height or its sturdiness. Barolo wanted the building to be an allegory of the greatest book ever written by one of his compatriots and the defining work of literature of his nation: Dante’s Divine Comedy.

He then trusted architect Mario Palanti with the task of creating a building that would enclose every metaphor and every symbolism of Dante’s masterpiece in every one of its aspects. The building needed to be 100 meters in height, no more and no less, to match the 100 ‘cantos’ in which the book is divided, and have the number nine (a recurrent number in Dante’s book, with its nine angelical choruses, nine gates of Hell, nine circles of Purgatory and nine spheres of Heaven) present in the nine gates of the building, as well as the 22 floors representing the number of verses in which each poem of the book is divided. Its basement represents Hell, while the middle floors represent the Purgatory, and the tower represents Heaven.

Barolo even envisioned having Dante’s mortal remains brought from Italy to rest in the building, which would then become his mausoleum.

But after finishing the building on June of 1923 at an exorbitant cost, Barolo needed a way to promote it in order to lease its already overpriced suites and offices, and the Firpo-Dempsey fight provided the right opportunity for a big publicity stunt: those who did not have a radio at home could come to Congress Square and look up towards the Barolo Tower, where a blue light would announce a victory by Firpo and a red one would do it for Dempsey.

The mausoleum had just become a lighthouse, and the old book by Dante was on its way to becoming the first chapter of a book of its own, a landmark in the lifelong search for hope and inspiration for thousands of men in modest black suits and unconquerable hope.

And the book would have many more chapters written under the same underlying subject of the Firpo-Dempsey heartbreak.

For many years to come, the subject of the “moral victor”, the man who could have achieved greatness if only the more powerful evil forces of the universe had not conspired to keep him down, became a recurring theme in Argentine sports – and in life in general.

Firpo’s perceived failure during the country’s rite of passage into the worldwide sports spotlight became the subject of continuous scrutiny and discussion through the years. The exact number of seconds spent by Dempsey trying to recover became a subject of national debate. The lack of a ‘neutral corner rule’ that allowed Dempsey to remain right by Firpo after each one of his trips to the canvas, hovering around like a bird of prey over his imminent victim, provided even more reasons for analysis.

During those seventeen seconds which started with Dempsey being punched and “seeing a million stars” (according to his own account) under the force of Firpo’s blow, Dempsey landed on a typewriter at ringside and was aided by several ringside reporters to get back into the ring. The rules back then allowed for 20 total seconds for a fighter punched out of the ring to get back in and continue fighting, but no one specified which part of those 20 seconds were supposed to count towards a stoppage count.

But the referee only reached a count of nine, and Dempsey was back on his feet unleashing a savage beating on Firpo, who fell nine times before the fight was stopped. The Divine Comedy had just added a couple of more nines to its long list of allegories.

The 17 seconds during which Firpo had a chance to grab the heavyweight title in what was Latin America’s maiden voyage into the stormy seas of pugilism became only the first of a long series of episodes in which an Argentine “almost made it,” only to be denied unfairly by the favorites or the preordained winners from more powerful countries. Or at least that became the perception in a country that seems to find as many reasons to aim for the stars as it does to find excuses in defeat

.

In 1968, Argentine golfer and British Open champion Roberto DeVicenzo was the victim of a series of scoring errors that cost him the Masters Tournament in Augusta, Georgia, when his partner Tommy Aaron incorrectly marked his card while the eventual winner Bob Goalby was benefited from a similar mistake in his own favor. Unwilling to win the title on an appeal, DeVicenzo allowed the mistake to stand and thus forfeited what could have been his second Major win.

In 1977, tennis legend Guillermo Vilas had a banner year that included a French Open and a US Open title, as well as a second place in the Australian Open, but failing to be ranked No. 1 by the ATP due to an unfairly outdated scoring system. A later investigation concluded that Vilas should have occupied the top of the rankings on several occasions during the ‘70s if the math had been right at the time, but Vilas refused to pursue legal actions to have this injustice corrected.

In 1981, Formula One driver Carlos Reutemann was winning one of the defining races of the season when the Williams racing team posted a sign by the road asking him to allow teammate Alan Jones to surpass him. Rebelling against his employer, Reutemann had his Rubicon moment and barged on to win to pull within one point of winning the title at the end of the season, only to be denied the championship in part by a decision to turn the South African Grand Prix into an unofficial F1 race due to disagreements within the organization. Had that race distributed points for its participants, Reuteman would have won the first F1 title for the country since Juan Manuel Fangio’s legendary five-title run in the fifties.

Nine years later, Argentina was seeking to repeat its Soccer World Cup success of 1986 in a final game at Italy ’90 against West Germany, in a do-over of the ’86 final game. With only five minutes left in a yet-scoreless game, Uruguayan-Mexican referee Edgardo Codesal awarded a penalty to the Germans for a largely non-existent foul. Germany went on to win 1-0 on the strength of the subsequent goal scored by Andreas Brehme, and the image of Argentine icon Diego Maradona crying inconsolably as he received his runner-up medal became a symbol of the country’s frustration of seeing injustice getting in the way of what they perceived as well-deserved achievements.

In spite of the country’s numerous sporting successes, the ghost of that fateful night in which a lone, towering Argentine boxer was denied the heavyweight championship of the world due to a technicality that he failed to dispute properly at the time came back repeatedly to haunt some of the country’s most outstanding athletes. Some of them tried to stand up to the slings and arrows of their outrageous fortunes, but most of them simply surrendered to the more comfortable escape through the high road, preferring the dry confines of the moral high ground to the muddy waters of the legal wrangling in which only the sore losers would rather dwell.

In Argentina, those 17 seconds echoed in eternity.

In 1923, Argentina was the seventh richest nation in the world. That title would prove just as temporary as Firpo’s time under the spotlight, as the country would unravel into a spiral of dictatorships, economic crisis and collective decay that would require Dante’s feverish narrative to describe. .

But for all that, there is no Dempsey or no obscure power behind the throne on whom to blame.

A few years after that fateful September night, the astronomer Edward Hubble finally got his wish and managed to use the largest telescope ever built to gather enough data to confirm his Nobel-prize worthy theory: stars (and the galaxies that hold them) tend to shift their light to blue when they are traveling towards their observers, and they turn to red when they are flying away.

For a fleeting moment, one night in September of 1923, a blue star was on its way to Argentina to announce the birth of a new Messiah that would lead a nation of illegal immigrants, destitute refugees, penniless pariahs and weary travelers to heights only known to greater civilizations.

It didn’t happen. But their eyes, however, remain on the blinking and ever-changing lights of fate shining from the mountaintop, settling for the more modest title of moral victors in a world where reaching the top of the podium, no matter how or with the help of how many ringside writers, is all that counts.

Firpo never won the heavyweight title. Reutemann never became Formula One champ. De Vicenzo never won a major tournament again. Maradona retired without ever playing a championship game again.

Hubble, as it turns out, never won the Nobel Prize for his discovery.

As Dante would have it in the Canto XX of his Inferno, “may God so let you, dear reader, gather fruit from what you read.”

An entire nation is still struggling to do so, even almost a century after its lucky star turned red, veered its course and flew away from them, never to be seen again.

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Book Review2 weeks ago

Book Review2 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles3 days ago

Featured Articles3 days agoThe Hauser Report: Debunking Two Myths and Other Notes

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRahaman Ali (1943-2025)