Canada and USA

The 50 Greatest Lightweights of all Time Part Four: 20-11

Lightweights – I must apologize for the endlessly spiraling word count. The difference between these fighters is tiny, but as the fighters get greater the increments by which they are separated become smaller and my explanations become longer. My advice to those still interested enough to read every word: do it in two spells.

That will be considerably fewer than the spells it took me to write it.

#20 – Barney Ross (72-4-3; Newspaper Decisions, 2-0)

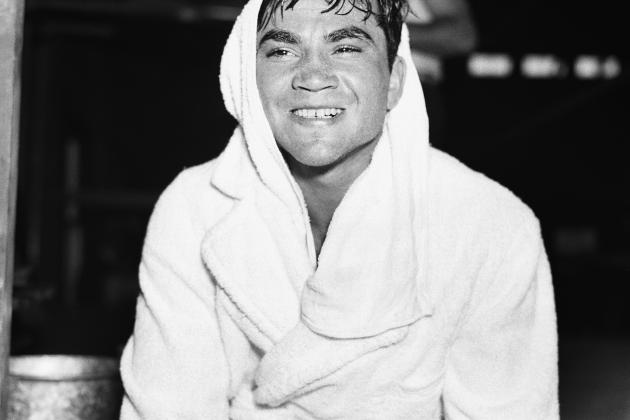

The mighty Barney Ross (pictured), all heart and speed and action, dropped a couple of decisions early in his career but from 1932 onward, he was a lightweight invincible. This is also the year he stepped up to the higher levels of competition.

He took a decision from the fighter that had been Ray Miller in August of that year, Frankie Petrolle and Battling Battalino in the following months, both of whom are more than trial horses. In early 1933 he moved on from Frankie to Billy Petrolle, but continued to win at a canter. Joe Gnouly was next, a fighter who had just pushed Benny Bass to a majority decision, and then those steering the precious cargo decided to chance it against the great Tony Canzoneri, with both the lightweight and light-welterweight titles on the line. The championship changed hands on a ten round decision in Chicago Stadium, Ross taking a majority decision based upon a brilliant left-handed performance in the last round, all hooks and jabs, baffling and driving back the electrifying Canzoneri.

The crowd didn’t care for the decision, although those at ringside were more clearly divided. The great Packey McFarland was ringside and felt it was Ross all the way; whichever side of that coin you prefer, the two rematched over fifteen in New York just three months later in front of 40,000, who witnessed another close, sometimes unsatisfactory affair, with the split going to Ross, who then departed the division, never to return.

This leaves us in a quandary. Yes, Ross is one of the very greatest fighters in history, but his ranking at lightweight is hung upon two desperately close wins over Canzoneri; without them, Ross just wouldn’t figure. There is, of course, the small matter of his being one of the very finest fighting machines south of middleweight, in the whole history of boxing, but I feel, nevertheless, that Ross can’t rank much higher here, based upon his actual achievements in the actual division: 2-0 in title fights, one successful defence.

#19 – Willie Joyce (72-21-10)

In March of 1943, Willie Joyce defeated Henry Armstrong over ten rounds in Los Angeles. Armstrong was past his prime, of course, but was riding a twelve fight winning streak going in, a streak that included victories over welterweight Fritzie Zivic and the excellent Juan Zurita. Slender at the weight, Joyce was as tough a fighter that ever lived; he was never stopped despite trading shots with some of the most hellish pressure fighters and punchers as has been assembled at the poundage. He didn’t need the full extent of that toughness to best Armstrong, however; he had the 3-1 favorite, “missing wildly” according to the Associated Press and took a close but clear decision. Elusive, stiff of jab and quick of feet, Joyce has sharpened his tools previous to his meeting with Armstrong against aggressive strong-man Slugger White, with whom he went 1-1. And yet Joyce enjoys not a tenth of the exposure enjoyed by some of his peers – a lack of quality scalps to accompany the Armstrong and White victories? No.

Just before his defeat of Armstrong, Joyce defeated the highly ranked John Thomas, heavily favored to beat him but outpointed by a “steaming” Willie Joyce who boxed with real aggression. Better yet, Joyce won an extraordinary four fight series with Ike Williams who, nobody will be surprised to read, holds a top ten slot. When Joyce first defeated the terrifying Williams, he was on an incredible fifty fight run during which he had lost just one engagement. This was the very streak which made Williams great, but Joyce brought it to a juddering halt in November 1944. Made an underdog once more, Joyce brought a withering left-hook to bear, both out-fighting and out-boxing the great Williams to eke out a ten round split. Williams avenged himself just weeks later in the rematch, but Joyce very nearly scored a stunning knockout in the process of taking a twelve round decision from him in March of 1945. Winning at a canter with his left-jab, it was a doorknocker right hand that stopped Williams in his tracks in the twelfth and saw him holding on. Williams fought him for a fourth time in June but the result was the same, this time over ten. Williams, a vaunted puncher, probably thought he had finally seen Joyce off in the tenth when he finally dropped him, only to have Joyce clamber off the canvas and deck him in turn.

It was the last word between them.

#18 – Bob Montgomery (75-19-3)

Bob Montgomery, out of South Carolina, was a part of the mad scramble to crown a new lineal champion in the wake of Sammy Angott’s 1942 retirement, finally losing out to Ike Williams who would go on to hold the title until 1951, a fact even more difficult for Montgomery to stomach given that in 1944 when he and Williams crossed swords, it was Montgomery who emerged with the victory.

Montgomery and Williams did not care for one another, the source of their bitterness remarks made by Williams about knockout victim Johnny Hutchinson, a sparmate of Montgomery. The spite seemed to infuse the punches in both contests. Williams was riding a thirty fight unbeaten streak into their first contest; Montgomery beat him mercilessly, tanning his body two-handed before dropping him face-first into the typewriters in the press-row in the final ten seconds of the twelfth and final round. As far as “watch your mouth” goes, it was a noteworthy effort.

Montgomery had already boxed a career by the time of that, the first knockout ever perpetrated against Williams. Before he had even fought two years as a professional, Montgomery was thrown in with Lew Jenkins who had beaten all-time great Lou Ambers four months earlier and was the reigning lightweight champion of the world. Montgomery drilled him to the canvas in the third and dropped a narrow non-title fight over ten. The Associated Press scored the fight a draw. Jenkins, in a bid to save face without putting too much on the line, provided a rematch and Montgomery provided a beating. Even more impressive, Lew’s “Sunday Punches” bounced “harmlessly off Montgomery’s jaw” while his own shots opened up three cuts on the champion, who declined to provide a title shot.

Montgomery fought aggressively from a crouch that put some sportswriters in mind of Henry Armstrong, an odd way for a tall fighter to approach boxing from a modern perspective, but actually not that rare in this time. It brought Montgomery victories over Beau Jack, Joey Peralta, Max Shapiro and Bobby Ruffin, all significant scalps. His resume is starting to read like one that would demand a higher ranking, but the kicker is that Montgomery lost to a lot of these men too. He went 2-2 with Jack, 1-1 with Shapiro and Williams avenged himself upon Montgomery late in his career.

But in his prime, and even before he hit his peak, Montgomery was a terrifying lightweight who was only denied the lineal lightweight championship by the matchmaking policy of Lew Jenkins’ management.

#17 – Henry Armstrong (151-21-9)

No, you are not seeing things. That’s Henry Armstrong, ranked in the teens, below fighters whose names you will not see mentioned among the greatest of all time.

Armstrong is one of the greatest fighters of all time, #4 on my pound-for-pound list and as reasonable a selection for #1 as exists. But he was also considered for the welterweight list published by this website (and will doubtless be considered at featherweight, too). No fighter is credited twice for any given fight; Armstrong’s movement through the weight classes was so fluid that he becomes one of the very few fighters affected.

In order to maintain internal logic, this project requires rules. The rules describe the weight range that will be allowed in judging whichever given weight class is being considered, in this case, lightweight plus 2.5lbs (it can’t be an exact weight range because the limit has changed over the years). Above this weight range, the contest is a welterweight fight, and the fighter was credited accordingly during that analysis. Armstrong, as mentioned in the introduction to part one, is the exception.

This is because Armstrong, during his astonishing twenty-plus welterweight title fights, sometimes fought against men who weighed in as lightweights, and weighed in as a lightweight himself. The question then becomes, is a welterweight title fight contested for the welterweight championship by two lightweights to be treated as a lightweight combat or a welterweight combat? I have taken the decision to treat it at welterweight. Therefore, Armstrong is not credited at lightweight for his welterweight title fights with the likes of Joe Gnouly (135.5lbs), or Baby Arizmendi (136lbs); he was credited at welterweight.

Apologies for the technicalities, but I feel it’s important that readers understand what it is that has led Armstrong to this slot.

Moving on to what he is credited for, it must be reported that Armstrong’s resume is not earth-shattering. His third most impressive win is probably over Baby Arizmendi. Arizmendi troubled Armstrong down at featherweight and he troubled him again in their 1938 lightweight contest, a toe-to-toe war that finished in a decision for Henry. His 1937 knockout of Benny Bass must rank as second, given that it is the only time in his career Bass was knocked out (he was stopped on his feet versus Kid Chocolate).

As for his best win, there is only one contender, his fifteen round split decision over world champion Lou Ambers from 1938. “I’m not going to bleed any more,” Armstrong told his corner between rounds as he beheld the slew of blood that had poured from his cut mouth onto the canvas, a fact that was making the referee a little uncomfortable. “I’m not going to spit it on the floor. I’m going to swallow it. I’m going to win this title. Take the mouthpiece out. Don’t give me no mouthpiece. Just let me go…”

And they did.

But he staged only one defense before losing it right back to Ambers one year later. Repeatedly penalized for low blows, as he was in their first fight, it made for a far less impressive title reign than that which Armstrong enjoyed at welterweight.

Naturally enough, this has led to a less impressive divisional ranking.

#16 – Sammy Angott (94-29-8)

Sammy Angott’s welterweight career was a disaster. He was battered from pillar to post by fighters like Sugar Ray Robinson, Ike Williams, Henry Armstrong; lesser lights, too, had their way with him. The first two years of his career were no kinder to him. A ledger of 16-10-2 details his shortcomings as a prospect. When he hit his lightweight stride, however, he did damage to the division so severe as to be directly comparable to that wrought by contemporary Lou Ambers.

It began for him with a trilogy against the sometime #1 contender Davey Day, who he “whirlwind punched” to a standstill in their first October 1939 contest, earning himself a unanimous decision. Day, who was famous for his slow starts, rallied wonderfully in the final two rounds of their rematch two months later to take a split, Angott perhaps hampered a little by his determination to stay busy, a fact that saw him beat no less a figure than Baby Arizmendi between his first two matches with Day. Whatever the truth of that, he won the rubber staged at the dawn of the 1940s to lift a lightweight strap.

By the end of 1941 he was undisputed and lineal having hoovered up the other lightweight belt taking names like Bob Montgomery and Lew Jenkins on the way, although he was beaten by a lightweight Ray Robinson in this period – something in which there is certainly no shame. Matching the bigger Robinson for a second time up at welterweight reeks of kamikaze; a few months after his second loss to Robinson, Angott retired amid the astonishing news that he had been fighting with a bum right hand ever since his 1940 contest with Montgomery.

This represents the end of Angott as a lineal champion, but he did return to the ring and with matching Robinson deemed futile he instead met Willie Pep. Pep, perhaps the greatest featherweight in history, was less lethal at lightweight but still represents a significant scalp; according to one ringside report, Angott won all ten rounds against the legendary Pep, an astonishing performance from the 3-1 underdog who certainly re-earned his nickname, “The Washington Windmill.” Allie Stolz, Slugger White and Bobby Ruffin were additional ranked victims in this second career which was dominated by his welterweight disasters but saw him continue his good work at lightweight.

At his best, Angott was brutal. He stayed close to his foe, punching perpetually and although he was too given to holding to ever become wildly popular he was still something of a fan favorite during his title years. Early inconsistencies and his injury-hampered run as king exercise some drag on his placement here, but he was a great lightweight and one who was never stopped at the poundage.

#15 – George “Kid” Lavigne (36-6-10; Newspaper Decisions 1-3-1)

In perhaps the finest era in lightweight history, George “Kid” Lavigne has not a single recorded loss during the first ten years of his incredible ring career although it is possible that he posted losses in bare-knuckle contests lost to the sands of time. But if, as the record books indicate, he turned professional in 1886 and didn’t post his first loss until 1897 when he dropped a couple of Newspaper Decisions in six round contests, that is as astonishing a feat as detailed in this series.

More astonishing, perhaps, are his dual wins over “The Demon” Joe Walcott. Walcott, even smaller than Lavigne’s 5’3, was the terror of his day, perhaps the hardest pound-for-pound puncher in an era that included the likes of Sam Langford and Aurelio Herrera. Their two contests fought two years apart for the lightweight title may have been the occasions upon which the two hardest hitters ever to share a ring met. So naturally, their first fight went the distance.

Things get a little complex now, in keeping with the traditions of the era. To obtain a title shot, Walcott had to agree to the title only changing hands in case of a knockout (much like a no decision bout). This limited him tactically, for obvious reasons. That said, despite the fact that he does not feature on this list due, in part, to these two losses and in part due to a lack of depth on his lightweight resume, seek and destroy was very much Walcott’s preferred approach. A legitimately thunderous puncher with a rough-hewn chin to match his bombs, Lavigne happily met him ring center. Each man had in his corner one of the greatest technicians of the pre-WW1 era, George Dixon seconding for Walcott, Tommy Ryan seconding for Lavigne, but their fight was a bloodbath; it ended with Walcott cut to the forehead and one of Lavigne’s ears sliced almost from his head but most of all with a Lavigne rally.

Still, the agreed rules make the reporting confused; was Lavigne greeted enthusiastically as a winner because he had actually won 8 or more of 15, or was it the case of an audience impressed with his bravery and pigmentation? Fortunately Lavigne cleared the matter up by re-matching Walcott in 1897. Still the world champion, he won on this occasion clearly, one California newspaper stating that “Lavigne whipped Joe Walcott and whipped him thoroughly.” Walcott quit at the end of the twelfth, weight-drained and battered.

Other notables dispatched by this lightweight ferocity include Kid McPartland, Andy Bowen and Jack Everhardt. As a combination of punch, heart and chin he may be unequalled at the weight. Or any weight.

But there was one man he could never beat.

#14 – Frank Erne (30-6-16)

Frank Erne’s legacy relationship with Kid Lavigne reminds me a little of that between Ken Buchanan and Ismael Laguna in the sense that Lavigne would have ranked above Erne had the two never met. That they did and that Erne proved the better of the two head-to-head just edges the Swiss in front.

According to The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, there was a sense by 1898 that Lavigne had gone back, and there were those who were willing to back Erne with cash for their fight that year; the result was a draw, but there were many in attendance who fancied Erne with the edge, and as The Eagle reported, had the fight been slated for twenty-five rather than twenty rounds, he might have got the job done.

Their rematch, fought ten months later, was slated once more for twenty and was fought in Erne’s hometown of Buffalo. Game to the core, Lavigne was in serious trouble as early as the seventh round and was saved only by the bell. Erne simply “battered his opponent out of the title” “never once losing his cool” as Lavigne strained with every sinew to remain upon his feet. It was a masterful performance from a speedy, clever, self-possessed fighter, perhaps one of the ring’s great jackals.

Between his first title tilt and his second, Erne took a moment to eliminate George McFadden from contention. As described in Part Three, McFadden became that year the first man to stop both Lavigne and Gans but found Erne a different matter. Erne also turned the trick with Gans, stopping him on a reportedly awful cut in the twelfth round of their title fight. McFadden, Lavigne, then Gans, it’s an astonishing trio of scalps and it took the phenomenon that was Terry McGovern to bring that run to an end, at a catchweight that stretched Erne across the bones. He lost his title in a rematch with Joe Gans who stunned all by blasting him out in a round, but only after staging one more defense against the wonderfully named Curly Supples.

#13 – Jack McAuliffe (28-0-10, Newspaper Decisions 1-0)

Dominated, as it is, by fight figures from the often distant past, it is likely that any modernists reading this installment of the series might become frustrated with its subject matter. Most beloved by the modernist is the hallowed “0”. Modernists, I give you the wholly unbeaten Jack “Napoleon” McAuliffe, the first of the lightweight boxing champions.

McAuliffe was bequeathed his nickname for the outstanding generalship during his title reign which ran from 1886 to 1893, whereupon he retired. Whilst labelling James J Corbett “the grandfather of boxing” is inaccurate due the fact that boxing evolved as a culture, not at the behest of a single champion, if that title is to be handed to anyone, it should be handed to McAuliffe. His “ring science” as his advanced technique was labelled in the press of the day was one of the defining attributes of his reign. More important given the ruleset of the day – finish fights were the norm – was his incredible stamina and endurance which saw him win through in numerous wars of attrition where punch resistance and durability proved even more important than technical acumen.

McAuliffe, originally out of Cork, Ireland, first came to prominence in twice beating Jack Hopper for the American lightweight title before besting Bill Frazier in an over the weight match in Boston, in 1886. This is the year from which McAuliffe’s claim to the world title is generally recognized, a recognition that birthed true legitimacy for the lightweight division. This led, in 1887, to his twenty-eight round knockout of Canadian Harry Gilmore in defense of the title. Such were the difficulties of finding premises for fights during this era of semi-legality that the two ended up contesting the world’s championship in either a barn or a blacksmith’s with three ropes barracking a structural wall which formed the fourth. It was the twenty-seventh round before Gilmore gave ground and the twenty eighth before McAuliffe “struck him fully ten blows to the face…Gilmore finally fell senseless to the floor.”

His next defense was perhaps the most extraordinary fight in the pre-history of boxing, a seventy-four round war with a cobbles fighter named Jem Carney (or Carnay). An Irish immigrant in Birmingham, England, Carney found work hard to come by but was welcomed to the blood-soaked arms of skin fighting like a son. He set his old ways against the new ways of McAuliffe in a contest that was decided over a period of hours, not minutes. In the early 1880s he killed a man named Jimmy Highland in combat and embarked for America as feared as any prizefighter ever was. Taller by an inch and younger by a decade, McAuliffe was favored but Carney just refused to be broken. Dropped three times in the very first round, by the forty-fifth he “seemed a sure winner.”

McAuliffe stayed with him but by the seventy-first was “a gone man” with his corner repeatedly claiming for fouls that either didn’t exist or that did but were generally accepted as the price of doing business. It was now McAuliffe who suffered repeated knockdowns when the social compact that bound such early prizefights together began to unravel. News reached the ear of the barn’s owner that it was to be torched if McAuliffe lost. What happened next is uncertain, but one story that is told sees Dick Roche, a gambler from St Louis who had backed McAuliffe big, rush the ring with a wrecking crew in tow and the ring collapsing. Even as Carney roared for the fight to continue the referee named it a draw. There was no rematch.

He crushed Billy Dacey the following year and then met the celebrated Billy Myer in another draw, this time over sixty-four rounds. Once more the fight was controversial, this time because it was not brutal enough, but a scientific encounter that contained much “sparring.” His defeat the following year of Jimmy Carroll, too, was revelatory, Carroll dominating the late stages only for McAuliffe to save himself with a single punch in the forty-seventh.

McAuliffe is a figure of huge importance in historical terms and the defenses he staged after Carroll – knockouts of Austin Gibbons and Myer in a rematch – help stoke his fire. Boxing in its infancy is hard to trace and there are some long shadows cast over McAuliffe’s legacy but I suspect that his placement just inside the top fifteen is about right.

#12 – Sammy Mandell (88-22-10)

When Canzoneri first came calling upon the lightweight division in 1929, Sammy Mandell gave him a bloody good hiding for his temerity. It was not a close fight. According to the Associated Press, Mandell gave Canzoneri “the boxing lesson of his life.”

Jimmy McLarnin was deemed ready for a title shot in 1928 having just obliterated Sid Terris, with whom readers of this series will be familiar. In but a single round, Mandell tore him into pieces, thrashed him blind in what the Associated Press named “the most important lightweight battle in the past five years.” Mandell had reigned for two of those years having taken the title from Rocky Kansas in 1926. Before being matched for the title he had slaughtered a red wall of ranked men, toughs like Jimmy Goodrich, Solly Seeman, Sid Barbarian and Terris, all of whom ranked in the top five at the time of their dispatch.

Once he had the title he held it for four years, and while the turning away of Canzoneri and McLarnin alone are enough to make it a storied reign, he found time to defeat Billy Petrolle, who pushed him far harder than either of those two more famous men.

Yet, in reading about boxing history it is possible to find tales of McLarnin and Canzoneri – and indeed, even of Petrolle – far more readily than it is to find stories about Sammy Mandell. He is listed neither upon the IBRO all-time top twenty, nor the top twenty-five at Boxing Scene. Having studied the lightweights it is my guess that Mandell is the most underrated of all of them, a true genius of a boxer who has hard to hit, quick to react and held so much poise as to perhaps be labelled liquid. Films show, quite clearly, that he was both faster and a more accurate puncher than McLarnin, at least at lightweight.

He doesn’t make the top ten for two reasons. First, the quality of the division’s history is such that some wonderful fighters are bound to miss out. Second, he had the title wrenched from him in 1930 by Al Singer who blasted him to the canvas four times in one round and sent him scurrying for an awful second career up at welterweight. Like Erne, having his title annexed in less than three minutes limits his standing among the other great lightweight champions.

#11 – Joe Brown (116-47-14)

Joe Brown has been unfashionable for so long it has almost become fashionable to laud him. So let’s get the particulars out of the way and explain what he is doing in the #11 slot up front: he is 12-1 in lightweight title matches. He defeated no fewer than three #1 contenders. He was champion of the world in six calendar years. These raw statistics are impressive. Behind them, is an impressive fighter.

After losing the title to the mighty Carlos Ortiz in 1962, aged 36, Brown’s career became a disaster; he won just twenty of the forty-six fights he slogged through. His championship years, however, were sparkling.

I would guess that he hit his absolute prime while in the ring with the champion, in 1956, in a non-title fight, contested above lightweight. That champion was Bud Wallace, the definition, perhaps of a caretaker but a fine fighter; such was the ease with which Brown defeated him, Wallace burst into tears in the dressing room.

In their rematch for the title, a disaster so severe befell Brown that many other men – even great ones – would have folded. He broke his right wrist, in just the second round, but fought so brilliantly with his left that the two knockdowns he scored in the fourteenth when he reintroduced his right were enough to bring him the title on a split decision. In the title rematch, he staged a successful first defense, busting Wallace up so badly that he was pulled at the end of the tenth.

Brown was a quick, spritely mover who relied upon mobility for his defense, and it worked. A fast, sharp jab was often a pre-cursor to a torpedo right hand that was responsible for many of his fifty-two knockouts. Over the years it has come to be accepted that Brown was solid, consistent, steady but not extraordinary – I don’t think that is true at all, and I don’t think that the readily available footage describes that position. But even if it did, Brown had one of the most exceptional title reigns in the history of the division, king for more than five years, posting better than two championship wins per year. The number one contenders he defeated – David Charnley, Paulo Rosi, Kenny Lane – are not now household names, but they were the next best fighters in his division. He brooked no resistance from these pretenders. Orlando Zuleta, Joey Lopes, Johnny Busso, Cisco Andrade and Ralph Dupas were also ranked when he fought them. It is often said of great champions that they “cleared out the division.” It’s almost never true, but in Brown’s case, I’ll stand the point.

Until Ortiz came along and battered “Old Bones” out of his championship. I suspect few fighters have cherished the title more when in ownership. Imagine, if you will, the champions that keep him from the Ten?

Lightweights / Check out more boxing news and videos at The Boxing Channel.

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Book Review4 days ago

Book Review4 days agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoOleksandr Usyk Continues to Amaze; KOs Daniel Dubois in 5 One-Sided Rounds