Canada and USA

Ex-Cons in the Prize Ring: A Cautionary Tale

Demond Brock, who won a minor WBC lightweight strap in his 13th professional fight, headlines the next boxing card at the Downtown Las Vegas Events Center, opposing Reynaldo Blanco in a 10-round contest on Friday, Nov. 18. Brock, a New Orleans native, is an interesting story. When he stepped out of prison in 2011, he was a 30-year-old man who had spent half his life behind bars. (In his early years in prison – it was an armed robbery conviction that put him there – he was something of a hard ass, subverting an early release for good behavior.)

All prisons are hellholes, but those in Louisiana offer prisoners a wide range of activities to relieve the boredom. The main campus in Angola houses the longest-running prison rodeo in the United States. At Angola and other facilities run by the Louisiana Department of Corrections, prisoners can join a boxing team.

Demond Brock took up boxing in prison and was a stalwart. In inter-prison competitions, he was reportedly 39-1. Upon his release, he pursued an amateur career, advancing as far as the quarterfinals at the 2012 U.S. Olympic trials.

Brock trod an unconventional path to becoming a main event fighter, but he is hardly the first boxer to have discovered a knack for boxing while serving time in prison. Other “alumni” include the amazing Bernard Hopkins.

Bernard Hopkins

In a piece that appeared in a 1922 issue of Literary Digest, the great lightweight champion Benny Leonard wrote an eloquent defense of boxing. “It has curbed the gang spirit; it has helped to refine countless boys,” he said. Bernard Hopkins is the poster boy for this dogma.

At age 17, a series of felonies on the streets of Philadelphia landed Hopkins in Pennsylvania’s Graterford Prison. Sentenced to 18 years, he served 56 months. During his stay he reportedly won Pennsylvania’s annual inter-correctional boxing tournament four years running in the middleweight division. Documentation is lacking, but Hopkins did box in prison and he emerged from his years of confinement a completely changed man.

Others with similar backgrounds were not as strong. Now things get messy.

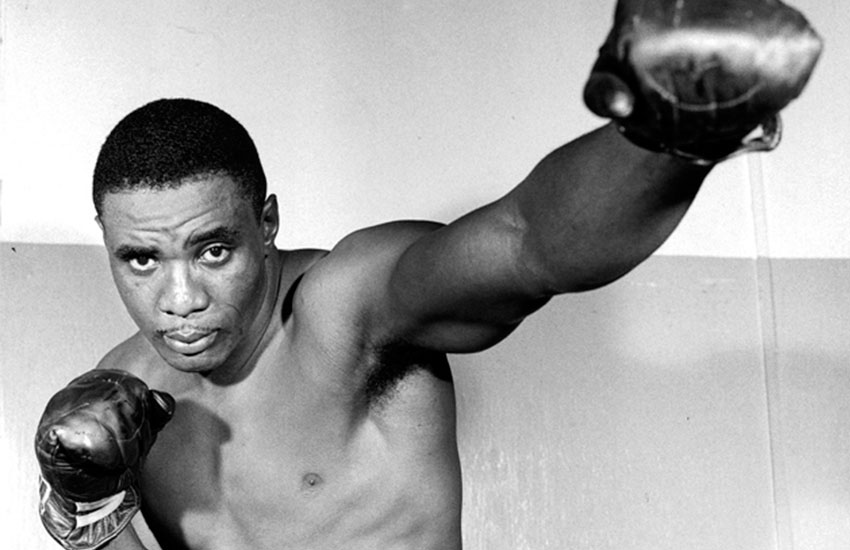

Charles “Sonny” Liston (pictured)

Two months shy of his 18th birthday, Liston was sentenced to two concurrent five-year terms in the Missouri State Penitentiary for a series of armed robberies. Encouraged to take up boxing by the prison’s Catholic chaplain, Liston was so scary-good that his would-be managers wangled an early release. In 1953 he won the National Golden Gloves tournament in Chicago in the heavyweight division. Nine years later he blasted out Floyd Patterson in the opening round to win the heavyweight championship of the world.

Ron Lyle

At age 19, Ron Lyle was sentenced to 15-25 years in the Colorado State Penitentiary for the fatal shooting of a Denver gang rival. Paroled after 7 ½ years, he used the skills he developed as a prison boxer to win a national AAU title before turning pro. Wins over such notables as Buster Mathis, Oscar Bonavena, and Jimmy Ellis earned him a crack at ruling heavyweight champion Muhammad Ali. He was ahead on all three scorecards when he was stopped in the 11th round. His 1976 Pier 6 brawl with George Foreman was named The Ring magazine Fight of the Year.

Floyd “Jumbo” Cummings

Cummings took up boxing at the Stateville Correctional Institution in Peoria, Illinois, where he served more than 12 years of a 50-75 year sentence for murder. He showed so well in supervised prison fights that he was allowed to compete in regular tournaments. An invite to the U.S. Olympic Trials was rescinded when it was discovered that the bylaws of the U.S. Olympic Committee prohibited the participation of prison inmates.

The highlight of Jumbo’s brief pro career, which he launched at age 29, was a 10-round draw with Joe Frazier, a fight he dominated in the eyes of most observers. (Smokin’ Joe, who was returning to the ring after a five-and-a-half year absence, would never fight again.)

Dwight Braxton

Braxton, who took the name Dwight Muhammad Qawi, spent 5-1/2 years in the New Jersey prison system for holding up a liquor store. Part of his time was spent at Rahway State Prison, the same prison that housed former middleweight contender Rubin “Hurricane” Carter.

Braxton, the Camden Buzzsaw, had no formal fights in prison, but reportedly spent much of his time at Rahway in the boxing gym. Standing only 5’7”, he won the WBC world light heavyweight title in his 18th professional bout without the benefit of any amateur experience. In his previous bout, he returned to Rahway a free man and outpointed inmate James Scott, a former prison sparring partner, in a 10-round contest that was nationally televised.

Braxton/Qawi was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame under his adopted name in 2004.

Bruce Seldon

Raised in the slums of Atlantic City, Seldon learned how to box while incarcerated at the Mountainwood Youth Correctional Facility in Allandale, New Jersey. In and out of prison as a teenager, he purportedly went on to become New Jersey’s inter-correctional heavyweight boxing champion. That’s hard to verify, but there’s no disputing that Seldon went on to win the WBA world heavyweight title, beating up Tony Tucker in a fight stopped by the ring physician after seven frames.

Clifford Etienne

Etienne, nicknamed the Black Rhino, took up boxing at Angola where he served 10 years on an armed robbery conviction. Paroled at age 26, he rose quickly up the ranks of heavyweight contenders. Victories over Lamon Brewster and former U.S. Olympian Lawrence Clay-Bey, both of whom were then undefeated, propelled him into a match with another unbeaten fighter, Fres Oquendo. He fared badly in that one – the match was stopped in the eighth round – and then things slowly unraveled.

Mike Tyson

A feral child, Mike Tyson had a rap sheet before he was 13 years old. At the Tryon School for Boys, a juvenile detention facility in upstate New York, he was introduced to boxing by Bobby Stewart, a counselor. Stewart was so impressed with Tyson’s potential that he brought the youngster to the attention of Cus D’Amato, the manager of former heavyweight champion Floyd Patterson. The rest, as they say, is history.

Henry Tillman

Tillman sparred with the law as an adolescent and it eventually caught up with him when he was remanded to the California State Prison Youth Center in Chino on an armed robbery conviction. There he met Mercer Smith, the facility’s boxing coach, who molded him into an Olympic gold medalist.

Tillman cashed his ticket to the 1984 Los Angeles games by turning away Mike Tyson twice in the Olympic trials, but as a pro he never made much headway despite a promising start. He retired with a record of 25-6.

The boxers on this list (with the glaring exception of Bernard Hopkins) have more in common than having learned their craft as youthful offenders serving time in prison. Dwight Muhammad Qawi and Ron Lyle managed to steer clear of serious jail time after being set free, but both walked a tightrope. Qawi struggled with alcohol and drugs before turning his life around and becoming a mentor to others fighting the same demons. Ron Lyle shot a man to death at his home in Colorado on New Year’s Eve, 1978. Released on bond, he was subsequently exonerated when a jury ruled that he acted in self-defense.

The others were recidivists.

SONNY LISTON was repeatedly in the news for brushes with the law. He was 15 fights into his pro career when an altercation with a St. Louis policeman put him back in the slammer where he served six months of a nine-month sentence.

MIKE TYSON famously served three years in an Indiana prison after a jury found him guilty of raping a beauty pageant contestant. Not quite four years after he was paroled, he was locked up for 108 days in a Maryland jail for a road rage incident. HENRY TILLMAN, who currently runs a boxing gym in Carson, California, was sentenced to 37 months in prison in 1995 for using a fake credit card to obtain money from a California gambling casino. He nearly went to prison again in 2004 when police stopped a car in which he was riding and found a large stash of fake driver’s licenses, forged checks, and counterfeit credit cards. In 1998, BRUCE SELDON was sentenced to 364 days in jail and five years probation for corrupting the morals of a minor, a 15-year-old girl.

The sad stories of JUMBO CUMMINGS and CLIFFORD ETIENNE make those stories pale by comparison.

In 1984, Cummings and another man were found guilty of attempted kidnapping and related charges in Michigan after an apparent paid “hit” went awry. In 2002, he was convicted of the armed robbery of a Chicago fast food-restaurant. The caper netted him only $250 and a videocassette, but it put him in violation of Illinois “three-strike” law and dictated that he spend the rest of his life in prison.

In the summer of 2005, Clifford Etienne went on a cocaine-fueled crime spree in his hometown of Baton Rouge, Louisiana. An armed robbery, a carjacking, and the attempted murder of a policeman (his gun jammed) were among the charges lodged against him. In June of 2006, a judge sentenced him to 150 years in prison.

*****

The bleak picture we have drawn is unfair to the “late bloomers” on this list who eventually got their house in order and became good neighbors and solid citizens. It’s also unfair to Demond Brock, who served his time and is entitled to a clean slate without any insinuations that he is prone to fall prey to the relapses that plagued so many ex-con boxers before him. However, in patching together this somewhat disjointed article, we couldn’t help but be reminded of something the great Hall of Fame boxing writer Dan Parker wrote in 1962. Parker, who believed that much of what passed for boxing journalism was propaganda, scolded his fellow scribes for being too quick to embrace the rehabilitation narrative.

As for Demond Brock, it should be noted that he got his GED in prison and completed a couple of college classes. “He is a great young man,” says Keith Veltre, the CEO of RJJ Boxing, Roy Jones’ promotional company. Jones, who has taken Brock under his wing, echoes that opinion.

With his chiseled, heavily-tattooed body, shaved head, and mutton-chop beard, Brock cuts a sharp figure in the ring. A high-pressure fighter, he routinely puts on a good show. In his last outing, he won a wide decision over previously unbeaten (14-0-1) Chuy Gutierrez, winning all 10 rounds on one of the scorecards in what was yet an entertaining scrap. “Both fighters traded shots like they were stuck in a phone booth,” wrote Las Vegas Review-Journal boxing writer Gilbert Manzano.

There are seven bouts in all on Friday’s show, the latest installment of the “Knockout Night at the D” series. First bell is at 7 PM. The Brock-Blanco match and two other bouts will air live on the CBS Sports Network at 9:00 pm PT/12:00 am ET.

Check The Boxing Channel for more boxing news on video.

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Book Review2 weeks ago

Book Review2 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles7 days ago

Featured Articles7 days agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRahaman Ali (1943-2025)

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoTop Rank Boxing is in Limbo, but that Hasn’t Benched Robert Garcia’s Up-and-Comers