Canada and USA

After 40 Years, the Rancid Decision in Everett-Escalera Still Stinks

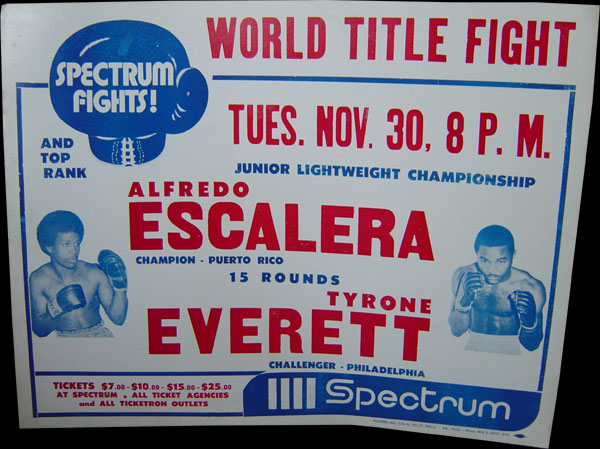

EVERETT-ESCALERA LIVES IN INFAMY — To hear some tell it, Nov. 30, 1976, was the night of the most brazen robbery since Jesse James, Bonnie and Clyde, John Dillinger and Willie Sutton were treating America’s banks as their personal ATMs. But those notorious outlaws made their withdrawals with guns instead of PIN codes.

Hotly disputed decisions are not uncommon in boxing, giving rise to any number of conspiracy theories that involve theft by pencil or some other form of official malfeasance. Few eyebrow-raising outcomes, however, have been so indelibly stamped with the infamy of WBC super featherweight champion Alfredo Escalera’s 15-round split decision “victory” over Tyrone Everett in the challenger’s hometown of Philadelphia. Adding additional intrigue to the heist is the fact that Everett was just 24 years old when he was shot to death six months after the Escalera fight, possibly as the result of his girlfriend discovering him in a tryst with a transvestite lover, possibly because of the slick southpaw’s financial backing of local drug dealers. In the two-story South Philly house where Everett’s brain was violated by a 32-caliber bullet fired from a pistol in the hands of Carolyn McKendrick, 38 cellophane packets of heroin were found on a dining room table.

The circumstances of his demise and the cutting short of what was shaping up as a brilliant ring career have served to make Everett a curious and enigmatic figure whose professional legacy remains a topic of discussion. The man known as “The Mean Machine” went to an unmarked grave with a 36-1 record and 20 wins inside the distance, but the memory of his many successes is forever overshadowed by the sole defeat that over the past 40 years has taken on the trappings of legend.

No one has ever been able to definitively prove that the fix was in that night at the Spectrum, but there is an old saying that holds if something waddles and quacks like a duck, and has webbed feet and a bill, it most likely is a duck.

Nigel Collins, boxing historian, former editor of The Ring and author of Boxing Babylon: Behind the Shadowy World of the Prize Ring, which includes a chapter on Everett, is convinced that, barring a knockout which would have undone the deal, it had been prearranged that Escalera would win so long as he was on his feet at the final bell.

“There obviously have been fixed fights,” Collins, who was at ringside for Escalera-Everett, told me for this story. “I can’t think of anywhere the hometown guy, the one who brought the crowd, wound up on the wrong end of such a blatantly wrong decision. I’d have to do some research on that.

“But clearly this fight was fixed. It was fixed by `Honest’ Bill Daly, who was a leftover from the era when gangsters overtly controlled the sport. That was really a dark day for Philadelphia boxing because so many people high up the totem pole were involved.”

Collins, however, makes it clear that he doesn’t believe Everett or any member of his support team were in on the alleged scheme.

“Everett clearly wouldn’t have agreed to anything like that,” he said. “I don’t think he would have lost on purpose if you had given him a million dollars. He had too large an ego.”

Makes sense; no fighter who had consented to go into the tank would have done the kind of paint job Everett did on Escalera with a fusillade of accurate and stinging counterpunches that, a generation later, would call to mind the artistry of another flashy southpaw, Pernell Whitaker. All of which casts at least a shadow of a doubt on the suggestion of a rigged outcome. If Everett was so highly skilled and capable of winning without assistance, how could any would-be manipulator be assured of getting the result he desired? Perhaps it was because Everett was generally disinclined to take unnecessary chances, settling for easy nods on points when he might have gone for exclamation-point stoppages.

“Everett was a very good fighter, lightning-quick, but he was a safety-first guy,” recalled J Russell Peltz, his promoter. “If he had more of a finisher’s instincts, not as many of his fights would have gone to the scorecards.”

A nice-looking fellow and reputed chick-magnet, Everett was not the typical Philadelphia fighter in that he never went in face-first, the better to protect his matinee-idol looks.

“People say I don’t like to get hit, and that’s true,” he once said. “They say I don’t look like a fighter, that I’m too pretty. I want to stay that way.”

So there is at least the possibility that the split verdict for Escalera owed to simple incompetence instead of corruption. But if that is indeed the case, the level of ineptitude rose to a Himalayan level.

In The Ultimate Book of Boxing Lists, which was compiled by Bert Randolph Sugar and Teddy Atlas in 2010, veteran boxing judge Harold Lederman states that it “may be history’s worst decision.”

Tom Cushman, one of my illustrious predecessors on the boxing beat for the Philadelphia Daily News, was among the ringside reporters who reacted with outrage at what appeared to everyone in the pro-Everett crowd of 16,119 to be a near-shutout romp for the fans’ favorite. Cushman, who scored the bout 148-139 for Everett (as did I, in reviewing the tape), summed up the prevailing reaction of virtually everyone concerned when he authored this opening paragraph of his fight story:

Tyrone Everett won the junior lightweight championship of the world last night. Won it with a whirling, artistic, courageous performance that brushed against the edges of brilliance. Tyrone was standing tall, proud, bleeding in his corner after the 15 rounds, waiting for the championship belt to be draped around his waist, when they snatched it from him. Picked him so clean it’s a wonder they didn’t take his shoes and trunks along with everything else.

Lest anyone think that Cushman had viewed the fight through rose-colored glasses and thus was predisposed to favor the hometown guy, it should be noted that representatives of every media outlet in attendance had Everett winning by similarly lopsided margins. Had CompuBox been operational then, the punch statistics favoring the Philadelphian surely would have as wide as the Grand Canyon.

But the only opinions that counted were those of Mexican referee Ray Solis, Puerto Rican judge Ismael Fernandez and Philly judge Lou Tress, and the scorecards they submitted elicited howls of anger and disbelief that might have produced a riot. Solis got it right by going with Everett, although by a surprising narrow 148-146 (4-2 in rounds for Everett, with an almost-incomprehensible nine rounds even), while Fernandez favored Escalera by 146-143 as did, shockingly, the Philly judge, Tress by 145-143.

Tress, who was 82 when he died on Oct. 13, 1979, hurriedly left the arena and he never again judged another fight. That might have been his choice, but more likely it was by popular demand.

“A day or two after the fight there was a story in the paper in which I was quoted as saying, `Lou Tress will never judge another fight as long as I’m director of boxing at the Spectrum,’” Peltz said. “And he never did, although I don’t think he ever tried to.”

Peltz was asked if the quote attributed to him is accurate.

“Yeah, I said it,” he confirmed. “I meant it, too.”

Tress is the linchpin of every conspiracy theory, the wild card who some have said accepted “a nice parting gift” for submitting a scorecard that seemingly flouted everything he had seen with his own eyes.

In Cushman’s book, Muhammad Ali and the Greatest Heavyweight Generation, there is a passage in which Peltz recalls encountering Frank “Blinky” Palermo, the Philly-based associate of New York mobster Frankie Carbo, a few days after Escalera-Everett. Peltz asked the notorious fixer, who was affiliated with Daly, if he thought some funny business had indeed gone down.

“You can buy Tress for a cup of coffee,” Palermo, who is now deceased, responded.

As it turned out, Tress was something of a mystery guest who arrived at the party at the last minute. Peltz and Everett’s manager, Frank Gelb, didn’t find out who the Philly judge was until the day of the fight.

“When we made the fight, Escalera’s people told us they didn’t care who the officials were,” Peltz said. “In our naivete, we were, like, `This is great.’ But what we didn’t realize was that they didn’t care because they knew the WBC would appoint the officials. That became a big, big bone of contention in the lead-up to the fight, almost to the point of the fight being canceled.

“Ed Snider, who owned the Spectrum at the time, got involved with the governor (Milton Shapp). I remember Linda (Peltz’s wife) and I going to a Flyers game and at a pregame party Snider said, `We got it done. We’re going to have one Pennsylvania (judge), one from Puerto Rico and a neutral referee.’ This was just a week or so before the fight.

“Really, we didn’t know it would be Tress until right at the end. But we figured that whoever the Philadelphia judge was, he was going to be honest. We expected the Puerto Rican judge, no matter what happened, to vote for Escalera if it went to a decision. And we were right; the guy turned out to be a complete crook. But we had investigated the referee from Mexico, and we were pretty confident that he was an honest guy, a fair guy.”

Team Everett anticipated that Tommy Cross, a former Philly fighter from the 1940s and ’50s, would get the judging gig for Escalera-Everett. But, Peltz said, there supposedly was a late conversation between Zach Clayton and Howard McCall in which Clayton, a former Pennsylvania State Boxing Commission head and referee (he was the third man in the ring for the Muhammad Ali-George Foreman “Rumble in the Jungle”), asked McCall, the then-commissioner of the PSAC, to appoint Tress as a favor to the old guy nearing retirement. McCall agreed, and the rest, as they say, is history.

Collins doesn’t know the identities of all those whose fingers were dipped into the rotten pie, but he does give credit to McCall for alleviating a tense situation when ring announcer Ed Derian read the decision that went over with the big turnout – the largest non-outdoors crowd ever for a boxing match in Pennsylvania – like a gob of spit in the punch bowl.

“McCall jumped into the ring, picked up the microphone and said he was suspending the decision pending an investigation,” Collins said. “Now, that was total b.s. There was no investigation, but his saying what he did probably stopped a riot from happening. The place was filled with Tyrone Everett fans and they were very angry, and had every right to be so.”

There was, of course, a public groundswell for Escalera and Everett to move on to an immediate rematch, but there were inevitable complications. Escalera – who insisted he deserved to win the controversial showdown with Everett because the challenger “ran, ran, ran, and you can’t win that way” – said the do-over would have to be in San Juan, Puerto Rico, which Everett and his crew were disinclined to do, given the fact they felt they had been screwed over on supposedly friendly turf. For another, Escalera had subsequently joined the promotional stable of Don King, ensuring that any negotiations would be contentious and drawn-out. Still, it was revealed a deal for Part II was in the works, although contracts had not been signed and might never have been.

Everything went up in smoke – gun smoke – when McKendrick fatally shot Everett on May 26, 1977. She pleaded self-defense, claiming that she had been the victim of domestic abuse by Everett on multiple occasions, and that she feared for her life as he stepped toward her in a menacing manner. Prosecutor Roger King argued that McKendrick shot Everett in cold blood because he had spurned her in favor of a transvestite, Tyrone Price, who was in the house at the time of the shooting. It should be noted that Everett’s family always has insisted that “ladies’ man” Ty, despite speculation, was not one to swing the other way.

The jury deliberated just 2½ hours before convicting McKendrick of third-degree murder. She was released from prison after serving five years.

What there was of the life and times of Tyrone Everett is destined to forever remain a blended jumble of facts and unsubstantiated opinions. While it is indisputable that he was a master technician inside the ropes, he never was afforded the opportunity to flesh out his career resume with more of the kind of defining fights that might have lifted him to the kind of status enjoyed by his stylistic successor, Whitaker, who was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 2007. Everett is enshrined only in the Pennsylvania Boxing Hall of Fame, which posthumously recognized him in 2006. There was not even a marker on his grave until John DiSanto, founder of phillyboxinghistory.com, established a program to place headstones on the otherwise nondescript final resting places of Philly fighters who deserved to be remembered. Everett, the first honoree, got his headstone in 2010.

Leave it to Peltz, who admits that his relationship with Everett was frequently frosty and adversarial, to speculate on how the superstar-in-the-making might have fared against such celebrated contemporaries as Alexis Arguello, Bobby Chacon (both of whom are in the IBHOF), Rafael “Bazooka” Limon and Cornelius Boza-Edwards.

“Escalera gave Arguello hell after the Everett fight,” Peltz, also an inductee into the IBHOF, noted. “They fought twice. I don’t know if both of those fights were life-and-death, but at least one of them was. Arguello was pushed to the max by Escalera and, let’s face it, Escalera was totally outclassed by Everett.

“Everett was lightning-quick. A lot of his fights weren’t exciting because they were one-sided, but if you look at the rankings, every time he fought at the Spectrum we brought in top-10 guys – Hyun-Chi Kim from Korea and Benjamin Ortiz from Puerto Rico, among others, and he handled them all. And he went on the road and beat Ray Lunny in San Francisco, his back yard. He went to Venezuela and beat Hugo Barraza in an eliminator in the rain. Who does that?

“Boza-Edwards, Limon, Chacon … they were used to guys walking to them, standing there and fighting at close quarters. Everett was a really slick, quick lefthander who always gave Hispanic fighters trouble. At the very least, he would have been competitive with any of them.”

And Whitaker, to whom Everett has frequently been compared?

“Well, they were both southpaws and they were both defensive fighters,” Peltz allowed. “Whitaker would stand in the pocket more and make you miss, which is what he learned from (his Hall of Fame trainer, George) Benton. Everett would move side to side and get out of there. But I don’t know that even Whitaker was as quick as Everett.”

Maybe it would all have turned out differently for Everett had he gotten the decision against Escalera he so clearly deserved. It is unfathomable to his admirers that in the 13th round of that miscarriage of justice, when a clash of heads opened a deep cut high on Everett’s forehead, that Escalera won the round on two official scorecards with the other even, despite it arguably being the challenger’s best work, in which he fought back with more passion than at any other time in the bout. It is Peltz’s position that had Everett only continued to go after Escalera the same way in the last two rounds, he would have won by knockout.

“The judges scored the blood instead of the punches,” Everett said of the most perplexing round of a most perplexing confrontation. Then again, maybe one or more of the pencil-wielders knew how they were going to score it before they saw it.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Book Review4 days ago

Book Review4 days agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoOleksandr Usyk Continues to Amaze; KOs Daniel Dubois in 5 One-Sided Rounds