Asia & Oceania

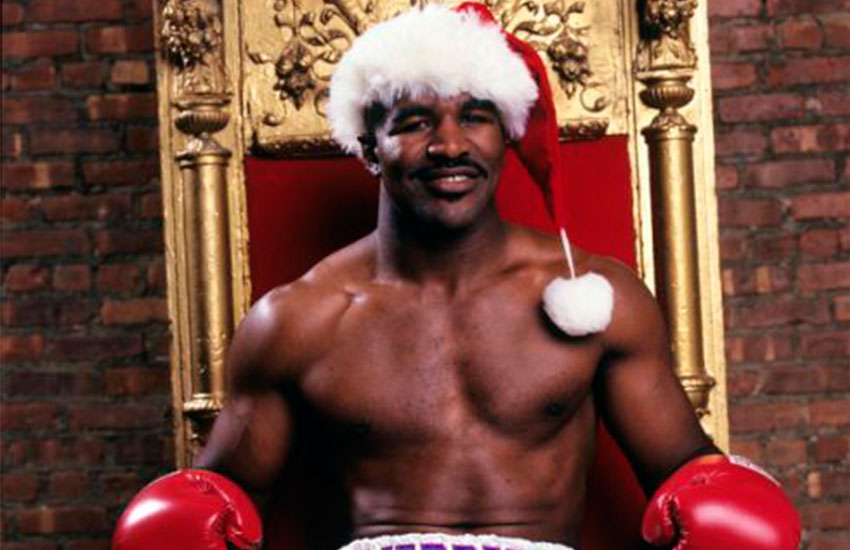

It’s a Landslide as Evander, Barrera, Tapia Enter the Boxing Hall of Fame

EVANDER, BARRERA, TAPIA CANASTOTA-BOUND — You say the outcome of last month’s Presidential election was a stunner? That the pollsters and pundits all (most, anyway) had it wrong?

The International Boxing Hall of Fame’s Class of 2017, which was announced Tuesday, offers no such controversy. All three of the impending inductees in the Modern category were strictly chalk, odds-on favorites for enshrinement, and the front man of the likely (voting totals were not announced) landslide is a four-time heavyweight champion whose selection was as assured as night following day.

Evander Holyfield has been a mortal lock to join other kings of the ring, as authenticated by the IBHOF, since … well, when? Did his inevitable journey to Canastota, N.Y., begin in earnest when he won his first world title by outlasting Dwight Muhammad Qawi to win a narrow majority decision for the WBA cruiserweight crown on July 12, 1986? Was it further legitimized when he unified the cruiser championship on an eighth-round stoppage of Carlos DeLeon on April 9, 1988? Even more so when he knocked out Mike Tyson conqueror Buster Douglas in three rounds to claim his first batch of heavyweight title belts on Oct. 25, 1990?

Was his future Hall pass indisputably carved in granite as the result of his classic three-act passion play with Riddick Bowe from 1992 to ’95, each bout a sort of Thanksgiving special staged in November? His pair of victories over Tyson, by 11th-round TKO on Nov. 9, 1996, and by third-round disqualification in the infamous “Bite Fight” on June 28, 1997? Could it be all of the aforementioned, and then some?

“Of course, the (first) Tyson fight,” Holyfield, 54, said when asked to single out a personal favorite from his greatest hits collection. “Oh, and the fight with Buster Douglas, where I became heavyweight champion of the world the first time. That really should be No. 1. I felt so good about beating Buster, but then people said he was fat and all that. It was like I really didn’t win nothin’. And me coming back to beat Bowe (in the second bout of their trilogy) absolutely was a big thing.”

Holyfield, who settled for a bronze medal at the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics but almost certainly would have taken gold had he not been wrongly DQ’ed by a referee in the semifinals, will be in good company on induction Sunday. The IBHOF mandates that the top three vote-getters in the Modern category, as selected by full members of the Boxing Writers Association of America and a panel of historians, qualify for induction, but in some years the field of eligible candidates lacks a trio of no-brainers. Such was not the case this time around as Holyfield (44-10-2, 29 KOs), aptly nicknamed “The Real Deal,” goes in with three-division (junior featherweight, featherweight, super featherweight) former world champion Marco Antonio Barrera (67-7, 44 KOs) and the late three-division (junior bantamweight, bantamweight, featherweight) ruler Johnny Tapia (59-5-2, 30 KOs).

Joining them will be Australian trainer Johnny Lewis, veteran Nevada judge Jerry Roth and the late ring announcer Jimmy Lennon Sr. in the Non-Participant category; longtime Showtime broadcast partners Barry Tompkins and Steve Farhood in the Observer category, and the late Eddie Booker (66-5-8, 34 KOs), a welterweight and middleweight contender in the 1940s and ’50s, in the Old-Timer category.

As is the case with a major Hollywood production, though, someone has to receive top billing, and the magnet to attract what is expected to be one of the IBHOF’s largest turnouts during the June 8-11 induction festivities is Holyfield, whose understated personality and stolid style sometimes masked his true greatness. But the humble, God-fearing man from Atlanta understood he had a date with destiny, even if not everyone thought so, and over time the number of those who doubted him melted away like late-April snow. Oh, fight fans came to recognize and appreciate Holyfield’s fundamentally sound skills, but what really won them over was his indomitable will. When push came to shove, Holyfield simply wanted to win more than many of his opponents. Barrera, 42, and the tormented Tapia, who was 45 when he died of heart failure on May 27, 2012, had a lot of the same inner drive to excel, to continually prove the naysayers wrong. It is an absolute necessity for any fighter who wants to not only get to the top, but stay there.

“I seen both of them guys fight and they were outstanding,” Holyfield said of Barrera and Tapia. “They were warriors who always gave the people their money’s worth. They fought just like me. They came to win. The only difference is that I was bigger than them.”

Maybe so, but Holyfield was often smaller, sometimes significantly so, than some of the XXL-sized heavyweights he sought out. At 6-2½ and a well-sculpted 218 pounds in his prime, Holyfield was like the little engine that could when paired against Bowe (6-5, 245), Lennox Lewis (6-5, 245) and, most obviously, then-WBA heavyweight titlist Nikolay Valuev (7-foot, 310). But you know what they say: it isn’t the size of the dog in the fight that matters, it’s the size of the fight in the dog. Inside the ropes, Holyfield was like a tenacious terrier that wouldn’t let go.

That owed in large part to his unshakable belief that there was always room for improvement, that his next performance always was going to be better than the one that preceded it.

“I never seen myself as great,” he said. “I seen myself as having the potential to be great. I believe that gets you to moving. If you start out thinking you’re great, it stops you from getting better. You’re, like, `OK, I did it.’ But you have to constantly motivate yourself to be the very best you can be. And you don’t ever want to think that you made it all the way there.

“After I knocked out Buster, some people said, `You’re the heavyweight champion of the world, you made it. Now you can quit.’ Quit? Man, do you know how long I waited to get to that point? Twenty years! I wasn’t about to just quit.”

And so he didn’t, hanging around nearly as long as has Bernard Hopkins, who presumably lowers the curtain on his career next weekend when, at 51, he takes on 27-year-old Joe Smith Jr. Holyfield was a well-worn but still feisty 49 when he fought his last fight, scoring a 10th-round TKO of Brian Nielsen on May 7, 2011, in Copenhagen, Denmark. But Holyfield’s determination to keep on keeping on began to ebb earlier than that, on Dec. 20, 2008, when he got a lump of coal in his Christmas stocking in the form of a disputed majority decision loss to Valuev in Zurich, Switzerland. Had he won, as many believed he deserved to, Holyfield would have added a fifth heavyweight title to his collection.

“I didn’t want to duck nobody, so when I realized (Wladimir) Klitschko wasn’t going to fight me, it was a waste of my time to keep going,” Holyfield continued, although he answered the bell for three more bouts before finally, and grudgingly, announcing his retirement.

By that time, though, even Holyfield had acknowledged that the time was right to step away. That realization presented itself in the form of a seemingly chubby sparring partner, Andy Ruiz, who obliged the living legend to question himself in a manner that no one else ever had.

“This kid I was sparring with, Andy something, who’s getting ready to fight (Joseph) Parker (for the vacant WBO heavyweight title Saturday night in Auckland, New Zealand), was, like, 21 or 22,” Holyfield recalled. “He was so fast, but he didn’t look like he should be fighting that good. His skills didn’t match the look of his body. That was the first time I can remember thinking, `Man, I don’t want to fight this guy.’ I never before seen somebody I would want to duck. I was never that way about nobody. My thinking always was, `I’m going to figure you out and find a way to beat you.’

“But that kid was so much stronger, so much faster than me. It made a difference. I knew it was time for me to go.”

Interestingly, Holyfield’s trip to Canastota for his induction will mark his first trip to a place that bills itself as “boxing’s hometown.” That, too, is by design. He even stayed away when some of those closest to him – trainer George Benton (2001, posthumously), co-trainer Lou Duva (1998), promoter Dan Duva (2003, posthumously) and 1984 Olympic teammate Pernell Whitaker (2007) – were enshrined.

“People tried to get me to go,” he said. “You know what I told ’em? I don’t want to go until I’m going to be in there (as an inductee). And that was it. If it’s meant to be, you go in when it’s your time. If I go again after this, it’ll be to see somebody else (inducted). Why take the joy away from myself that I’d get from seeing the place for the first time? When that time came, I wanted it to be because I had earned my way there.”

That he did.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Book Review2 weeks ago

Book Review2 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles7 days ago

Featured Articles7 days agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRahaman Ali (1943-2025)

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoTop Rank Boxing is in Limbo, but that Hasn’t Benched Robert Garcia’s Up-and-Comers