Canada and USA

On Marco Antonio Barrera and The Father of the Left Hook to the Liver

MARCO ANTONIO BARRERA AND “THE FATHER” — Marco Antonio Barrera, “The Baby-Faced Assassin,” will soon see his plaque up on a wall in the same Canastota hall as other ring greats. It’s the ultimate recognition of a career that spanned four decades, 75 fights, and numerous accomplishments. It’s also a career that nearly ended prematurely – twice. Just before his third professional match, a member of the local commission noticed what appeared to be doctored papers regarding Barrera’s age. It soon came to light that the 17-year-old boxer from the Mexico City neighborhood of Iztacalco was only 15. Revoking his license was considered briefly but, ultimately, he fought on with no interruption until 1996 when a more serious threat to his career surfaced.

They felt like cramps, he said. All over his body. He figured the cramps were a side effect of training. He learned to live with the cramps like a sewer worker learns to live with the smell. Then one day, in the presence of his mother Rosa who previously warned him that the cramps were something more serious, one of those “cramps” turned his face red. More than career threatening – they were life threatening. Blood leaked onto his brain from what was reported as either a malformed cluster of capillaries or a ruptured vein. Surgery was performed by Dr. Ignacio Madrazo. The surgery was a success and shortly after, within months, Barrera was boxing again. Boxing better than ever some felt. Some of his best performances came after the surgery. Erik Morales, Naseem Hamed, Johnny Tapia, and Paulie Ayala were among those he defeated. When Barrera finally did stop boxing, he had scored 67 wins including 44 by knockout. Like many of the other 12 Mexican boxers in the Hall of Fame, one his go-to-punches was the left hook to the liver.

They used to say that even the “winos” threw left jabs in Philadelphia. At one point, it could have been said that in Mexico City – in the Barrio of Tepito in particular – they threw left hooks to the liver. Tepito is considered the worst neighborhood in a city where even the downtown hotels lock down their entrances with padlocks at night. Taking up approximately three square miles just north of the city’s center, it’s a place of misery and mystery. Even the origin of the name is uncertain. Some say it derives from an Aztec word. Others say it was named after a cop’s whistle. Pito is Spanish for whistle and legend has it that a cop once said to his partner, I’ll go this way and, if I need help, I’ll whistle for you – “Te pito.”

It’s an area where Mexico’s heavily armed police seldom patrol, embassies advise against visiting, and pretty girls flash gang signs. If you ignore the warnings and visit, you’ll find the Tianguis street market. It’s a seemingly endless maze of tables and stalls shaded by bright colored tarps. Spread out on the tables are designer label clothing and handbags – both legit and bootleg – CDs and DVDs with blurry covers, and stolen electronics. Venture beyond the market, into the heart of the barrio, and you’ll find places where you can sit elbow to elbow with some of the hardworking residents of Tepito and enjoy some of the best stews, carnitas, or huevos con machaca in the country. Some of them will tell you the neighborhood’s nickname – Barrio Bravo – doesn’t mean “fierce neighborhood.”

It means “angry neighborhood” they say, dating back to the days when the last Aztec ruler, Cuauhtémoc, was held captive there before being assassinated. Others disagree. It does mean “fierce neighborhood” but the name derives not from the high crime but from the many boxers who came from the neighborhood, sometimes pointing to where those boxers used to live.

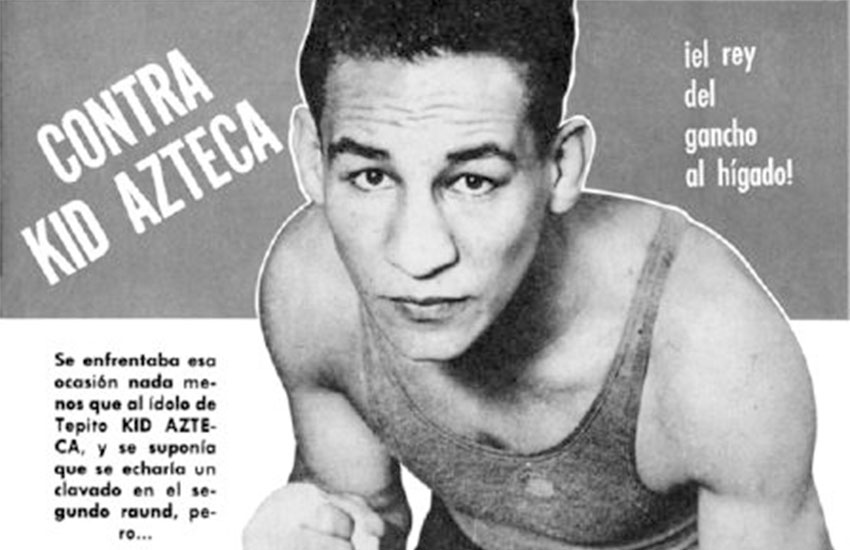

The boxing history is so rich that the B-line Metro station that stops in Tepito sports a boxing glove as its logo. And during the glory days of the 40s and 50s, when boxing was one of the more popular things to watch on canales doz, quarto, y cinco, many of the fighters featured came out of the barrio. One of those fighters, the one who lived at 19 Jesus Carranza – just a block or two from where the “fortress” used to stand – was the father of the left hook to the liver.

That punch was responsible for many of Kid Azteca’s 114 recorded knockouts. It was also responsible for his first stoppage loss. He was introduced to the pain of a liver blow early in his career when matched against Texan Tommy White, who fought frequently in Latin America and once held the Mexican welterweight title. White favored throwing body punches and against Azteca in 1932, one of those punches landed on Azteca’s liver. Azteca froze then sagged to his knees. While ringsiders shouted for him to get up, the momentarily paralyzed Azteca had an epiphany.

Before the referee finished his count, Kid Azteca made the decision to start aiming for liver in his subsequent fights. He practiced it until he became intimate with it. Some say he perfected it. Whenever Azteca maneuvered his way in front of an opponent and bent his left knee and dipped his left shoulder slightly, it was usually too late for his opponent. Azteca would go on to defeat White in a rematch. He also defeated Fritzie Zivic. And Ceferino Garcia. And Battling Shaw. And Cocoa Kid. And about 200 other boxers, according to Azteca. Close to three hundred fights he said he had when speaking of a career that saw him box all over Texas, California, Mexico, Guatemala, Panama, Cuba, and Argentina.

It started serendipitously when he was a 15-year-old on his way to the river for a swim. Having recently moved north near the U.S. border with his mother, Luisa Paramo, and a brother, he and a friend passed by an arena with fights going on. Wanting to get in but with no money, he and his pal were looking for a way to sneak in when a free pass literally landed on his lap. One of the show’s organizers stepped out of the arena in search of a replacement when he came upon the two. Which one of you wants to fight, he asked. Azteca pointed to his friend and his friend pointed to Azteca. They never made it to the river that day. For four pesos, Azteca climbed into the ring for the first time and boxed under his real name of Luis Villanueva Paramo. A few years later, trained and managed by “Cuyo” Hernandez, he was national champion. It was a title he held for more than 16 years and successfully defended 60 times, say Mexican sources.

When Azteca climbed out of the ring for the last time, he was a national idol, movie star, a friend of famed actor Cantinflas, mayors, governors, and even presidents. Some of the movies he appeared include Kid Tabaco, En Busca de un Campeon, El Gran Campeon, and the classic, Guantes de Oro. That film saw him reunited with other Mexican ring legends including Chango Casanova, Luis Arizona, Rodolfo Ramirez, El Conscripto Lopez, and many others. In that movie, he played the role of trainer and advisor to an upcoming fighter. It was a role he assumed in real life too. He generously gave advice and shared tips with many boxers including Raul Macias and “Gato” Gonzalez. And up until the very end of his life, he unselfishly taught many young boxers how to throw the left hook to the liver.

Azteca lived to be 88. They were scandal-free years. He never married, because he “was too busy boxing.” Azteca spent the last few years of his life alone in a 250-square-foot apartment two train stops away from his old neighborhood of Tepito. But he never complained. The 600-peso per month pension he received from the World Boxing Council and the Mexican Boxing Commission gave him just enough to pay the utilities and “buy some beans.” He died in 2002 – just long enough to see Marco Antonio Barrera bounce back and salvage his Hall of Fame career.

When you go to the Hall of Fame in Canastota don’t go looking for Kid Azteca’s plaque. For some reason, his plaque is not up…yet. But he’s there in spirit. You’ll feel his presence when you stand before the plaques of the other Mexican ring warriors that adorn the walls. Because they may not have gotten there without the help of that punch that Kid Azteca adopted, nurtured, made his own, and shared with all of Mexico. Olivares, Pintor, Cuevas, Zarate, Chavez, and many others. They’re all indebted to Kid Azteca. As is Marco Antonio Barrera, who also got an assist from Dr. Madrazo.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

Editor’s note: Jose Corpas’ second book, a biography of Panama Al Brown, titled “BLACK INK: A Story of Boxing, Betrayal, Homophobia, and the First Latino Champion,” is available now via Amazon and other leading online booksellers. Jose’s next book, tentatively titled “THE RIVALRY; Mexico vs. Puerto Rico,” will be released in 2017.

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Book Review4 days ago

Book Review4 days agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoOleksandr Usyk Continues to Amaze; KOs Daniel Dubois in 5 One-Sided Rounds