Canada and USA

Pep vs Saddler: The Underappreciated Arch-Rivalry

WILLIE PEP AND SANDY SADDLER — Saturday, Feb. 11, marks the 68th anniversary of Willie Pep’s most celebrated ring performance. It came in the second of his four meetings with Sandy Saddler, a gladiator with whom he had so much in common.

Pep and Saddler both turned professional at the tender age of 17, both fought with a frequency (a combined 403 bouts) that would confound far-less-active modern boxers, and both were featherweight champions so highly regarded that they were part of the International Boxing Hall of Fame’s charter induction class of 1990.

But Willie Pep (229-11-1, 65 KOs) and Sandy Saddler (144-16-2, 103 KOs), both now deceased, were also markedly different in their approach to their craft. Pep – born Gugliemo Papaleo in Middletown, Conn. – was perhaps the greatest defensive fighter of all time, a target so cleverly elusive that a sports writer for the New York Journal American, Bill Corum, dubbed him “Will o’ the Wisp,” which suggested the futility of someone trying to put wind-borne smoke into a bottle. The great columnist Red Smith, then with the Chicago Sun-Times, wrote that “If Willie had chosen a life of crime, he could have been the most accomplished pickpocket since the Artful Dodger. He may have been the only man that ever lived who could lift a sucker’s poke while wearing eight-ounce gloves.” And this, from poet Philip Levine, who described the 5-foot-5 Pep as “tiny, white perfection.”

Pep’s stick-and-move disappearing act was a natural outgrowth of a piece of advice he received from an older boxer at the outset of an amateur career in which he would eventually go 62-3. “When you’re in the ring,” the 15-year-old Pep was told, “make believe a cop is chasing you. Don’t get caught, don’t get hit.”

Saddler, a lean 5-8½ with a much longer reach and ebony complexion, was a physical as well as stylistic opposite of Pep. He was a relentless stalker, not a nimble retreater, with breathtaking punching power augmented by what British journalist Harry Mullan described as “a highly refined mastery of the ignobler aspects of the Noble Art. There have been few better featherweight champions, and even fewer dirtier ones.” Born in Boston to parents who had emigrated from the Caribbean, he learned the rough arts on the streets of Harlem after his family moved to New York. A tactic sometimes employed to telling effect by Saddler, who had a perfectly legal and devastating uppercut, was to sometimes miss on purpose in order to catch the other guy with an even more-damaging elbow to the face on the follow-through. Mike Tyson, an avid student of old fight films when he was coming up under Cus D’Amato in Catskill, N.Y., is said to have developed his own Saddler-influenced version of a foul that often goes undetected by less-than-vigilant referees.

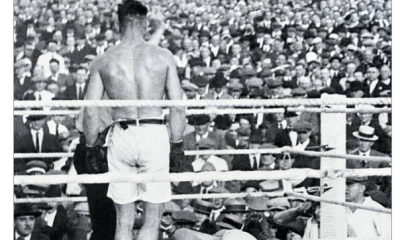

It is the beauty of boxing, however, that opposites can mesh in such a way that ring magic is produced. Pep and Saddler engaged in a four-bout series that was, at various intervals, fire and ice, silk and sandpaper. Saddler won three of those bouts, which might lead one to conclude that he was the better of the two antagonists, but that remains a topic open to debate. Two of the four clashes ended early with Pep citing injury while leading on the scorecards. The boxing master’s sole victory came on an exquisite, 15-round unanimous decision in the second installment, on Feb. 11, 1949, in Madison Square Garden, enabling Pep to regain the 126-pound title he had relinquished to Saddler on a fourth-round knockout on Oct. 29, 1948, also in the Garden.

It is the fourth and final confrontation, on Sept. 4, 1951, at the Polo Grounds, that separates Pep-Saddler from other classic rivalries that might now seem staid by comparison, no matter how hot the action between the ropes. This time Pep engaged Saddler in a gutter brawl that was all sandpaper and no silk, Saddler retaining his featherweight championship when Pep, again up on the scorecards, did not come out for the ninth round because of a badly cut right eye that might have become more damaged as the result of Saddler’s frequent departures from Marquess of Queensbury niceties. But to be fair, Pep attempted to match Saddler foul-for-foul, and for the most part succeeded.

Al Abrams, the sports editor of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, wrote that it was “the worst exhibition of unsportsmanlike conduct I have ever seen in a bout anywhere.” Nat Fleischer, editor of The Ring, weighed in that it was a fight with “wrestling, heeling , eye-gouging, tripping, thumbing – in fact every dirty trick known to the old-timers.”

How outlandish and numerous were the dirty deeds? Referee Ray Miller, a former lightweight contender, admonished both fighters to clean up their act so often that he nearly went hoarse, and he went down himself in the seventh round while again trying to separate the combatants during another rules-skirting clinch. Miller finally took a point from Pep that round for unnecessary roughness, but in truth he could have used an Abacus for all the subtractions he might have made on each side.

At ringside was the newly appointed head of the New York State Athletic Commission, Robert K. Christenberry, who called it the “roughest fight ever staged in our city,” and who shortly thereafter revoked Pep’s boxing license and indefinitely suspended Saddler.

Interestingly, Pep-Saddler IV was part of a big double-bill in the 13 movie theaters nationwide – this was in the infancy of closed-circuit – that showed the fight along with Flying Leathernecks, starring John Wayne as a Marine fighter pilot in World War II. But even “The Duke” likely would have been impressed by the violence level exhibited by two fierce and determined competitors, neither of whom was much larger than one of the beefy actor’s legs.

Why isn’t Pep-Saddler more celebrated, or at least more remembered, than other boxing rivalries of more recent vintage? It might be because, while history is forever, memories aren’t; the last of their four bouts was 65 years ago, and fight fans old enough to have seen any or all of their blood feuds are dying off, as did Pep at 84 in 2006 and Saddler at 75 in 2001. Maybe it’s because, at his best, Pep was an early, probably better version of, say, Guillermo Rigondeaux, who has been deemed poison to premium-cable outlets because he generally prefers to win by taking few risks and making the other fellow look foolish. Where Pep was boffo at the box-office in an era where ring artistry was more appreciated, today he’d have to slug more and dance less to appease the masses. And there are two entire generations of boxing buffs who hold that if they haven’t seen a TV fight in living color and high-definition, it’s like it never happened.

We all would like to believe that greatness endures simply because greatness must, but it is human nature to celebrate that which we have seen with our own eyes. That is why there are those who will insist that Floyd Mayweather Jr. is better than was Sugar Ray Robinson, and Mike Trout is better than was Mickey Mantle. But for those who take the time to scrounge up old fight footage, Willie Pep comes alive again as Fred Astaire with a stinging jab, and Sandy Saddler as the pursuing cop that Pep once was advised to avoid, and whom he later grudgingly admitted was “a terrifying guy.”

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel.

-

Book Review4 weeks ago

Book Review4 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Debunking Two Myths and Other Notes

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoNikita Tszyu and Australia’s Short-Lived Boxing Renaissance

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoKotari and Urakawa – Two Fatalities on the Same Card in Japan: Boxing’s Darkest Day

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoIs Moses Itauma the Next Mike Tyson?

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoBoxing Odds and Ends: Paul vs ‘Tank,’ Big Trouble for Marselles Brown and More

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 340: MVP in Orlando This Weekend