Canada and USA

The Richie Sandoval Story: Hard Times and High Times for a Knight of the Prize Ring

To say that former world bantamweight champion Richie Sandoval had a boxing career marked by highs and lows would be a great understatement. Sandoval was on cloud nine after earning a berth on the 1980 U.S. Olympic boxing team. Then President Jimmy Carter demobilized Richie and all of his teammates, enacting a boycott in protest of Russia’s invasion of Afghanistan.

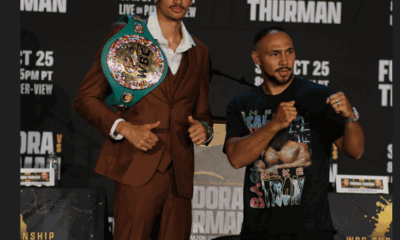

As a pro, Sandoval (on the left with former WBO welterweight champion Jessie Vargas and the noted trainer Ismael Salas) scored one of the bigger upsets of the 1980s when he dethroned WBA 118-pound kingpin Jeff Chandler. The lineal bantamweight champion, Chandler was making his 10th title defense. In a shocker in Atlantic City, Sandoval took Chandler apart, winning almost every round before the referee called a halt in the 15th stanza.

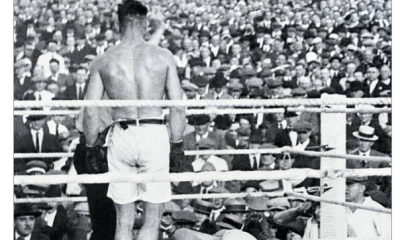

Not quite two years later, on March 10, 1986, in his third title defense, Sandoval was stretchered out of the ring unconscious at the outdoor arena at Caesars Palace. “I’ve been witness to three ring fatalities,” said a grizzled British scribe to the man seated next to him (me), “and all of them,” he rued, “looked just like this.”

Sandoval would never fight again, but his life was spared thanks to the fast work of ringside physicians, paramedics, and doctors skilled in treating traumatic head injuries. It was truly a miracle that he left the hospital with no visible scars of his harrowing ordeal.

Born in 1960, the youngest of five children, Sandoval was raised in Pomona, California, a blue collar city in Los Angeles County that today is 75 percent Hispanic. His father, who was born in Texas, worked in a battery factory. The Sandovals lived in a modest home across from a municipal golf course.

The location was perfect for a boy with an entrepreneurial spirit. Periodically a golf ball would come flying over the fence and roll into the front yard. Richie would gather them up, stash them away in an empty egg carton, and then sell them — two for a dollar if the traffic would bear, three for a dollar, whatever. He recalls the first time he mustered up the courage to trespass. After scaling the fence, he advanced stealthily to the little pond that served as a water hazard. Eureka, he struck the mother lode. The pond was full of wayward golf balls.

Pomona has long been identified with teenage street gangs. Sandoval wasn’t sucked in. There was too much on his plate. At age seven, he followed his two older brothers, Joseph and Alberto, to the basement boxing gym in the original building of the Sacred Heart Catholic Church where restaurant owner Tony Cerda, a former boxer, taught neighborhood boys the rudiments of the sweet science. In high school he joined the cross country team. It was important to earn that varsity letter jacket. For relaxation, Richie pursued his hobby of drawing. “His sketches and caricatures are quite accomplished,” said Los Angeles Times boxing writer Richard Hoffer in 1983 when Sandoval was juggling his nascent boxing career with commercial art classes at Mt. San Antonio Junior College.

Joseph Sandoval was a good amateur, but fell in with the wrong crowd and his pro career never took flight. Alberto, commonly called Albert, was a highly decorated amateur who went on to have a solid pro career, retiring at age 26 with a record of 33-5. A hot ticket seller at LA’s fabled Olympic Auditorium where he had 37 of his 38 pro fights, Albert “Superfly” Sandoval unsuccessfully challenged Lupe Pintor for the WBC world bantamweight title in 1980, the same year that Richie’s dream of Olympic glory was short-circuited by President Carter.

Had Richie been allowed to compete, he would have made more money on the front end of his pro career. He signed with a strong promotional firm, Top Rank, but like others in his weight class without the chit of an Olympic medal, his future earnings were restrained by a low ceiling. His laid-back demeanor was also a hobble. “I would have made more,” notes Sandoval wryly, “if I had been more like Hector Camacho, but that wasn’t me.” His purse for his final fight — and he was the defending champion! – was $37,500.

As a pro, Sandoval burst from the blocks with a flourish, winning his first 10 fights by knockout. He was undefeated in 22 starts when he wrested the title from Philadelphia’s heavily favored Chandler who was 33-1-2 going in and had avenged his lone defeat. In his two successful title defenses he turned away Venezuela’s Edgar Roman in Monaco (UD 15) and Chile’s Cardenio Ulloa in Miami Beach (TKO 8).

In a throwback to an earlier era, the lacuna between his second and third title defense was filled with four non-title bouts. Two of these were staged in his hometown in the gym of Cal Poly-Pomona.

Sandoval was then 25 years old and still growing into his body. He weighed 127 ½ pounds for the last of the four non-title bouts, nine-and-a-half pounds above the bantamweight limit. And with his title defense looming less than five weeks down the road, Richie was in a race with time to pare off the pounds in a way that wouldn’t sap his strength and his stamina.

“I told Cerda (his trainer and co-manager) that I couldn’t make the weight anymore, it was time to move up,” recalls Richie, “but he said ‘it’s for the title, so let’s do it one more time.’ He bought me my first pair of boxing shoes when I was seven years old and had trained both my brothers and co-managed Albert, so he was almost like a member of my family. I didn’t want to disappoint him.”

Nowadays, weigh-ins are normally conducted the day before a fight. That allows a boxer time to rehydrate and restore muscle. Nevada was one of the first states to mandate this practice, but in the spring of 1986, when Richie locked horns with Gaby Canizales, the rule hadn’t yet been implemented and he was compelled to weigh in on the day of the event.

Gaby Canizales, from Laredo, Texas, wasn’t quite as good as his younger brother Orlando Canizales who holds the record for successful bantamweight title defenses (16) and was ushered into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 2009, but Gaby, who had won 32 of his previous 34 bouts, was a formidable opponent. With his dark features he looked like a prizefighter, resembling a smaller version of Roberto Duran.

Sandoval-Canizales wasn’t even the co-feature. That distinction went to the NABF middleweight title match between Thomas Hearns and James Shuler. In the main go, undisputed middleweight champion Marvin Hagler was pitted against undefeated James “The Beast” Mugabi.

Sandoval recalls that there was a light rain falling when he entered the ring. He recalls almost nothing about the fight itself. The last round is a complete blank.

In the very first round, Sandoval was on the deck, put there by a looping right hand that countered a lazy jab. In the fifth round, a left uppercut from Canizales sent him reeling into the turnbuckle. Referee Carlos Padilla gave him a standing eight count. In the seventh, visibly fatigued, he was dropped three times. When he hit the deck for the third time, he appeared to have a seizure. Ringside doctors rushed to his side. Fifteen minutes elapsed before he regained consciousness. By then he was in an ambulance. A neurosurgeon rode with him to the hospital.

Even when a life is spared, these stories rarely end happily. Boxing is replete with tales of starry-eyed young men who enter the sport with next-to-nothing and leave with even less. What would become of Richie Sandoval now that his boxing career was finished?

Top Rank honcho Bob Arum stepped up to the plate. When Sandoval left the hospital, there was an envelope waiting for him. It contained a bonus check in the amount of $25,000 and a letter stating that henceforth he would be receiving a check every week: “compensation for work you will be doing for us in the public relations field.”

Not quite seven weeks later, Richie was in Roberto Duran’s camp at the Palm Canyon Hotel in Palm Springs, California, where Duran and featherweight champion Barry McGuigan opened their training camps for their forthcoming matches on Bob Arum’s next big show. They sparred with their sparring partners, jumped rope, and worked the bags in a big tent erected on the grounds of the resort. The bilingual Sandoval shadowed Duran right through to the formal weigh-in on the day of the fight, serving as his liaison to the English-speaking media.

Training camps can get lonely, but boredom wasn’t a problem because Richie was paired with legendary New York press agent Irving “Unswerving Irving” Rudd. Born in 1917, the gregarious Rudd was a great storyteller with a bottomless reservoir of great stories to tell. “What a great guy to learn the ropes from,” says Sandoval, looking back at those golden days.

That was 31 years ago and Richie Sandoval is still a Top Rank employee. A personal assistant for lack of a better title, he is frequently found minding the store at the Top Rank Gym. Unmarried, he has a 22-year-old son playing baseball at a small liberal arts college in California.

Richie’s signature moment at Top Rank occurred when he talked Bob Arum into signing Michael Carbajal. Arum needed convincing. He had a hard time selling Sandoval to the TV networks and here was a boxer, albeit an Olympic silver medalist, who was even smaller. Michael Carbajal wasn’t even a flyweight; he was a light flyweight who competed at 108 pounds.

“What am I supposed to do with him?” Arum purportedly said. “But this kid is special,” said Richie pleading his case.

Indeed he was. “Little Hands of Stone” won his first world title in his 16th pro start and raised the bar, at least temporarily, for fighters in his weight class. The first of his three encounters with his great rival Humberto Gonzalez was the first flyweight fight to command top billing on a pay-per-view show and the first flyweight fight in which the purses exceeded $1-million dollars. (And Carbajal, who commanded the larger share of the swag, earned every penny, clawing out of a deep hole to stop Gonzalez in The Ring magazine’s Fight of the Year.)

In February, Richie Sandoval and Michael Carbajal were named to the Nevada Boxing Hall of Fame. How appropriate that they are members of the same induction class, the fifth since the non-profit was founded. But there’s a bigger irony here.

Richie and his fellow inductees will be formally enshrined at a gala dinner on Saturday, Aug. 12, the culmination of Hall of Fame Weekend, a two-day event. The dinner is being held at Caesars Palace in a banquet room a literal stone’s throw from where the ring was pitched for Richie Sandoval’s final fight.

He left the premises that night lying prone on a stretcher, his life seemingly ebbing away, and on Aug. 12 he will be back, walking on a red carpet with a spring in his step. In the real world of boxing, heartwarming stories aren’t as common as Hollywood would have it, but here is one of them.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel.

-

Book Review4 weeks ago

Book Review4 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Debunking Two Myths and Other Notes

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoNikita Tszyu and Australia’s Short-Lived Boxing Renaissance

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoKotari and Urakawa – Two Fatalities on the Same Card in Japan: Boxing’s Darkest Day

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoIs Moses Itauma the Next Mike Tyson?

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRamirez and Cuello Score KOs in Libya; Fonseca Upsets Oumiha

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoBoxing Odds and Ends: Paul vs ‘Tank,’ Big Trouble for Marselles Brown and More