Canada and USA

Juan LaPorte and the Mysterious Death of Salvador Sanchez

It was close to noon on August 12, 1982 when the radio blurted out four times in Spanish, “Salvador Sanchez is dead – I repeat – Salvador Sanchez is dead!” Each time the announcer repeated those words, my jaw sank lower and lower. Weeks later, at the corner store, at Vinny’s barbershop around the corner, and on every stoop on the block, everyone still shook their heads in disbelief. In our neighborhood, Sanchez was considered almost invincible and stood alongside Sugar Ray and Duran as the best boxers in the game. That belief was not the result of opinion but, rather, stemmed from the expert testimony of that tough featherweight who lived on the other side of Pratt Institute who we called Tony La-Por and the rest of the boxing world knew as Juan LaPorte.

Back in those days, during summer weekends when boxing was on network television, Ralphie on the first-floor would push his Magnavox to the window and turn it so that the screen faced out. Outside, in front of his window, the old timers used to set up a folding table, pull out the cards and dominoes, and pop open the Buds while the kids gathered in a semi-circle behind them, bumping shoulders and jockeying for a better view of the action. When the slugging heated up, like it did during the final rounds of the Saad Muhammad-Marvin Johnson fight, the playing cards went face-down and all eyes focused on the window. On the day Sanchez stopped Danny Lopez for the second time, the playing cards remained untouched and nods of approval filled the street. A few months after that, when LaPorte challenged Sanchez for the title, a bunch of us crammed into Ralphie’s living room and glued our eyes to the set.

I was still too young to leave the block by myself but some in the room knew LaPorte since he was an amateur winning all the newspaper tournaments. Others said he was among the toughest street kids in a rogue city where sneakers were swiped off people’s feet and nearly the entire police force once called out sick at the same time. From Fulton Street to Myrtle Avenue, between Washington and Throop Avenues, merely mentioning his name – he’s La Por’s cousin – was enough to get a fella out of a tight bind. In between rounds of the Sanchez-LaPorte fight, stories like the one LaPorte told the NY Times were shared. “First fight I had,” he told the paper, “I knocked the guy’s tooth out and he swallowed it. We’re now best of friends.”

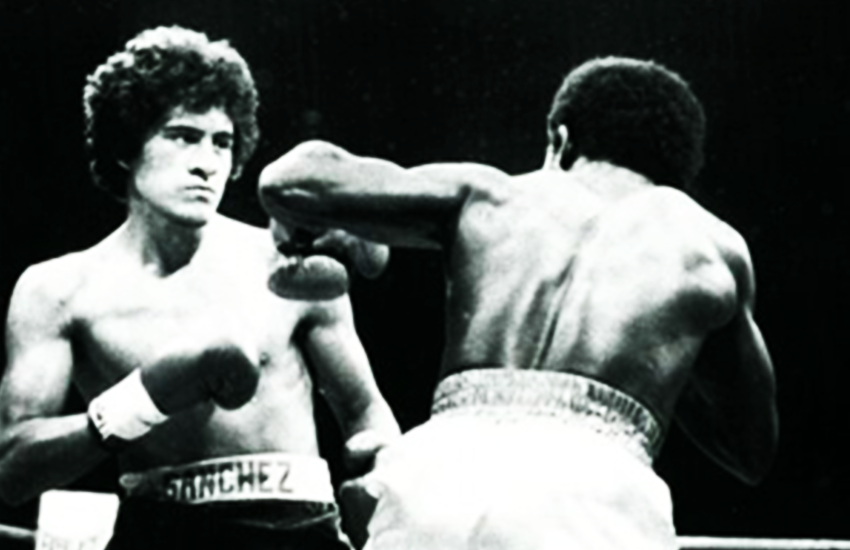

After 15 gallantly fought rounds that ended with Sanchez telling “Juanito” that he was a future champion, the two became best of friends. Just before Sanchez made his defense against Azumah Nelson (pictured in the white trunks), he gave LaPorte, who was fighting on the undercard, a pair of boxing gloves as a gift. Less than a month after receiving the gloves, LaPorte was among the hundreds who lined the streets of Santiago Tianguistenco that rainy Saturday when Sanchez was buried.

On August 11, 1982, Sanchez had begun training for a September 15 rematch against LaPorte. At approximately 3:30AM the next day, on an unlit highway that sliced through the hills, along kilometer 14, his speeding Porsche 928 was sent crashing head on with an oncoming truck in the opposite lane. The Times write up stated that local police had determined that Sanchez was driving at “high speed” when he crashed into a “heavily loaded tractor trailer.” His death, according to the Times, “stunned and puzzled Mexican sporting circles.”The Spanish-language news informed viewers that Sanchez’s car was rear-ended by another truck, the impact sending the Porsche into the oncoming lane where it collided with another truck.

Despite the conflicting reports and lack of details, reports agreed that Sanchez was the type of fighter who never broke camp.

When training, he strictly followed a 9PM curfew and each morning, at precisely 5:30, did his roadwork throughout the dirt roads of San Jose Iturbide with his trainer following closely behind in a car. The twenty-three-year-old never left camp without informing someone, according to his trainer, Cristobal Rosas. The afternoon of August 11, the routine was broken.

Alejandro Toledo traced the final steps of the champion in his book, De Puño Y Letra. Sanchez spent the morning shadowboxing and during lunch, he received a phone call that made him restless, according to the witnesses Toledo spoke with. Sanchez grabbed his car keys and sat quietly while rattling them impatiently in his hand. He mentioned wanting to take his car to Queretaro to have his mechanic look at the horn, which he claimed was acting up. Rosas told him not to bother, that he passed by the day before and the mechanic was away. Another person at the training camp said Sanchez told him he wanted to go into town to purchase a new album. Someone else said he believed the champ had a mistress in Queretaro and had gone to see her.

Who it was that called Sanchez and what was said remains uncertain. Around 4 o’clock that afternoon, without advising anyone, Sanchez got into his car and drove to Queretaro.

Reports say he did visit the mechanic, left empty handed, and, according to some, spent the next few hours hanging out with “admirers” until 2AM. Others said he was at a bar until 1AM.

According to all sources, Sanchez was by himself when he pointed his headlights north towards San Jose Iturbide, a not-quite one-hour drive when traveling at the speed limit. Regardless of whether he left a 2AM or 1AM, Sanchez, behind the wheel of a speeding Porsche, should have been back in camp before 3 o’clock.

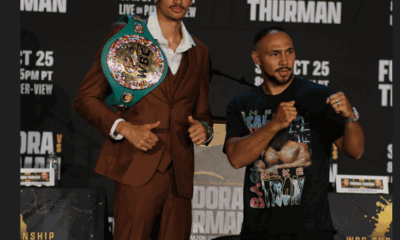

On September 15, 1982, LaPorte stopped Colombian Mario Miranda in New York to win the title left vacant by Sanchez’s death. He trained in the gloves Sanchez gave him. When I met him for the first time, he was a former champ looking to bounce back after a loss to Barry McGuigan.

I was classmates with LaPorte’s cousin, a Golden Glover who had once won the “Nobody Beats The Wiz Boxer of the Night” award. We were sitting on the couch in his cousin’s apartment off Taaffe Place, our BVD tank tops still damp from a mile-long run, when LaPorte walked in and tossed a snake onto his cousin’s chest. Because it was one of those thick, heavy, scaly snakes that have taken over the Everglades, his cousin calmly freaked out. “It’s just a baby,” LaPorte laughed while lifting it off his cousin’s chest. A disturbance in front of the house caused us all to run outside. An attempted chain snatching was thwarted when LaPorte, snake wrapped around his shoulders, ran out into the street and chased away the two would-be thieves.

Years later, at a gym in Brooklyn, I reminded him of that day when he looked like the Tarzan of the concrete jungle. “That sounds like something I would’ve done,” he laughed. Like Sanchez, he was a disciplined fighter. Everyday around noon, whether he had a fight scheduled or not, he’d arrive at the gym, often by himself. He worked on his jab, his footwork, all the basic things. Whenever the gym was crowded, unlike some pros, who cut in front of the line of amateurs waiting to use the bags because they had a 10-rounder coming up, LaPorte waited his turn. When he shadowboxed in the ring, he didn’t reserve the ring ahead of time nor insist that he be the only one in it. Instead, he blended in with a group of boxers of all ages, and practiced his feints, ducks, and combinations.

Many found it easy to cheer for him, witnessed by the hundreds from the neighborhood who populated the upper deck of The Garden when he beat Miranda and, again the night he went toe-to-toe with Julio Cesar Chavez in a fight that looked to us like he won and that Chavez himself said he would not have complained if LaPorte got the win. The day after the Chavez fight, the New York Daily News said it was a close fight that drew boos from the crowd, “though not vehemently.” Had that reporter been seated where we were, he would’ve noticed that the reason some didn’t boo loudly was because they were too busy shaking their heads in disbelief since, once again, the local lad had been dealt a bad hand, though not as bad as the one he was given when he challenged Panamanian Eusebio Pedroza for the WBA belt at Atlantic City back in 1982.

Pedroza was a great fighter who also carried a gym-rep of being a dirty fighter. There were unverified accusations of stimulant use that fueled his late round rallies and Lou Duva publicly accused Pedroza of using an illegal substance in the corner during Pedroza’s fight against Rocky Lockridge. Pedroza often hit below the belt, on the break, on the kidneys, and after the bell.

Against LaPorte, his corner showed the world a different trick. After being staggered in the second round, the round in which Pedroza began throwing low-blows and kidney shots, ringside commentators Tim Ryan and Angelo Dundee informed viewers that Pedroza’s corner administered smelling salts between rounds. Ammonia capsules, LaPorte would later say. The fouling worsened after that round. LaPorte fought much of the final rounds off the ropes, he said, to protect his kidneys from the illegal shots.

After the fight, Dr. Edwin Campbell of New York issued a report detailing the extent of LaPorte’s injuries. He found “contusion to the scrotum, testicles and lower back … that were clearly the result of excessive trauma to an extent that I have rarely observed in my 25 years experience.”

Over 50 flagrant fouls the New Jersey commissioners counted. Pedrozawas warned 16 times but only three points were deducted. Both the New York and New Jersey commissions reviewed the fight and reversed the decision and declared LaPorte the winner. Three other states followed suit. But the Panama-based WBA ignored the state commissions, the fouls, and the smelling salts. Pedroza remained their champ.

In the gym and on the block, LaPorte was considered the champ. Though he never hesitated to state his side, LaPorte didn’t complain too much after the Pedroza fight. If he fouled back, he felt, he could’ve been disqualified. He rightfully could have complained after the fight as loudly as PaulieMalignaggi did when Paulie got a raw deal in Texas in his first fight with Juan Diaz. He could’ve complained too in 1983 after he got into a limo with Don King and a trusted member of his own camp, who allegedly sold LaPorte out and forced him to sign a deal with King, rather than with Madison Square Garden and Paul Guez, the president of Sasson. Rumors surfaced in the Spanish media that threats were made against LaPorte and his family if LaPorte did not sign with King. Afterwards, King threatened LaPorte, Guez, Madison Square Garden, the Garden president of boxing operations John Condon, and LaPorte’s manager, Howie Albert with lawsuits.

“They compared me to Al Capone or some mafioso,” King told the UPI. “On the contrary, that’s not true. That’s a defamation of character and character assassination…I intend to file suit.”

In his next two fights, a demoralized LaPorte, fighting much like the so-called “Lost Heavyweights” of the 1980s, sleepwalked his way to consecutive losses, including one against Wilfredo Gomez. Whatever happened in that limo ride was never fully revealed but it was enough to bring tears to LaPorte’s eyes.

We all shed a tear with him that sad day in 1989 when his eight-year-old son drowned in the same Sheepshead Bay waters that the body of former bantamweight champion Joe Lynch was found in back in 1965. Though a pair of officers held LaPorte back, keeping him from jumping off the concrete pier and into the unpredictable waters, a piece of him was left in the chilled waters of that Atlantic. When news of the drowning reached the neighborhood, by word of mouth and later, on the evening news, even the mothers who never saw him box and only knew of him from those Lo Mejor de lo Nuestrocommercials on channel 41, cried and said a small prayer.

LaPorte, at his best as good as any Hall of Famer, was perpetually at the drawing board – his prime vandalized by a tainted sanctioning body and a hostile limo drive. The neighborhood’s best days had passed too. By the time the 1980s ended, nobody played stickball or cocolevio anymore, too many were smoking from glass tubes or were under the supervision of the DJJ, and LaPorte had moved. I never got around to asking LaPorte about Sanchez and the questions surrounding his death. Some twenty years later, at a Golden Gloves show in Manhattan, I shook hands with the former champ for the first time in decades and caught up on the past. Instead of asking him about Sanchez, I asked him about the snake.

“He just died,” he said. “Not too long ago.”

When LaPorte arrived home from work one frigid evening, he found the snake dead amid two rabbits and a suddenly faulty heater. Everything was working fine when he left that morning, he said, and his initial inspection didn’t reveal any clues to the cause. Then he checked the cord and it all made sense.

Did anyone check the “cord” after Sanchez died?

If Sanchez left the bar at 1AM, he would have reached kilometer 14 around 1:20AM. Even if he left an hour later, there remains a large chunk of unaccountable time during his final hours. Who was it that called him that afternoon and what did they say to make a champ who was never flustered in the ring become restless. Where did Sanchez spend those unaccountable moments? Did he fall asleep for a while on the side of the road? Did he go somewhere else? What were the trucks doing on the road, especially the one that struck him from behind?

At approximately 3:30AM, on his way back to his training camp, on a flat, straight section of the highway, Sanchez’s white Porsche was rear ended by a truck and sent crashing into an oncoming truck. The mangled hood of his Porsche was pushed back near the windshield, which lay in shattered pieces on the front seats. Both trucks involved were Dina Tortons. They were heavy duty trucks powered by either International or Cummins engines and were, unlike the Porsche with its 143-mph factory top speed and sub-seven 0 to 60 times, built for carrying heavy loads. Reports stated that after surveying the damage at the crash scene, investigators had no doubt Sanchez was speeding when his car collided. What the published reports didn’t state was an explanation for that question that’s lingered in my mind since that day the radio announcer repeatedly stated that Salvador Sanchez had died. If Sanchez’s car was rear-ended, then why was the Dina Torton that struck him speeding too?

Editor’s Note: Jose Corpas’ second book, a biography of Panama Al Brown titled “BLACK INK: A Story of Boxing, Betrayal, Homophobia, and the First Latino Champion,” is available via Amazon and other online booksellers. He is currently at work on his next boxing book, tentatively titled “THE RIVALRY: Mexico vs. Puerto Rico.”

To comment on this article at The Fight Forum, CLICK HERE.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel.

-

Book Review4 weeks ago

Book Review4 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Debunking Two Myths and Other Notes

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoNikita Tszyu and Australia’s Short-Lived Boxing Renaissance

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoKotari and Urakawa – Two Fatalities on the Same Card in Japan: Boxing’s Darkest Day

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoIs Moses Itauma the Next Mike Tyson?

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoBoxing Odds and Ends: Paul vs ‘Tank,’ Big Trouble for Marselles Brown and More

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 340: MVP in Orlando This Weekend