Featured Articles

CORBETT OVER SULLIVAN WAS 1892 PREDECESSOR TO MAYWEATHER-McGREGOR

Corbett over Sullivan – A compelling case can be made for the heavyweight championship bout that took place on Sept. 7, 1892, in New Orleans as the biggest.

CORBETT OVER SULLIVAN – What a difference 125 years makes.

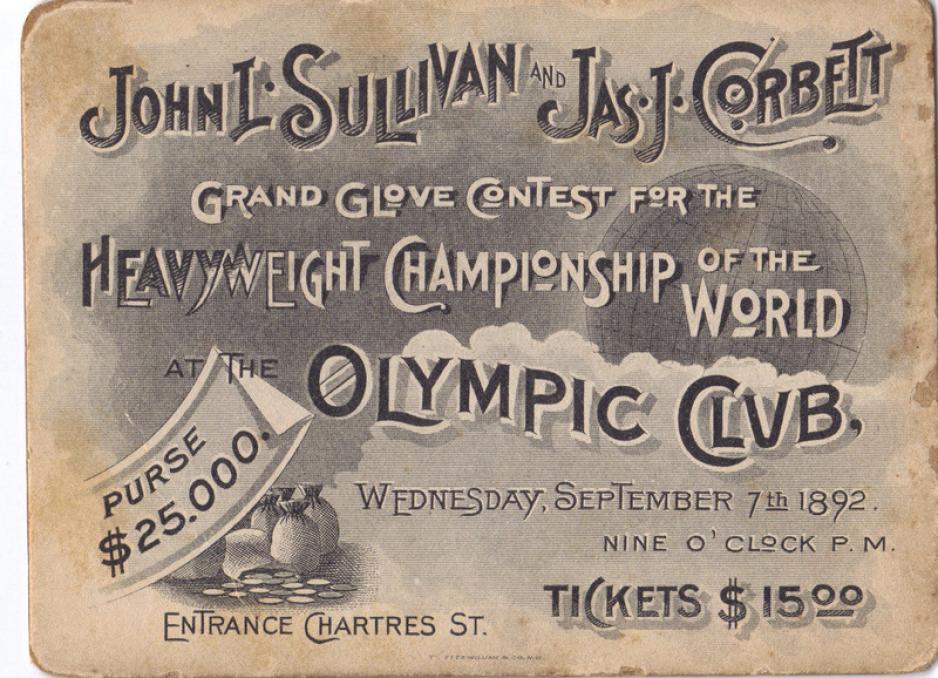

While several boxing matches have claimed, with varying degrees of legitimacy, to be the biggest, most important of all time – think Johnson-Jeffries (July 4, 1910), Louis-Schmeling II (June 22, 1938), Ali-Frazier I (March 8, 1971) and, if you’re solely going by amount of money generated, Mayweather-McGregor on Aug. 26 – a compelling case can be made for a one-sided heavyweight championship bout that took place on Sept. 7, 1892, at the Olympic Club in New Orleans.

“Gentleman” Jim Corbett’s 21st-round knockout of long-reigning bare-knuckle champ John L. Sullivan, the “Boston Strongboy,” lifted a sport that previously had been existing on the fringes of respectable society, viewed either with marginal acceptance or as an outright criminal enterprise, as the harbinger of a new era that has not only existed but flourished to this very day. For historical purposes, let it be noted that Corbett’s upset of the favored Sullivan predated Mayweather’s 10th-round stoppage of McGregor by 125 years and 12 days.

The framework for Corbett-Sullivan was provided by the Marquess of Queensberry Rules, so named for an English lord named John Douglas, the ninth Marquess of Queensberry, but actually authored by a Welshman, John Graham Chambers, in 1865. Published in 1867, the Queensberry Rules’ mission was to make the “art of pugilism” less barbaric. No wrestling or “hugging” was to be allowed, with rounds to be of three minutes’ duration and one minute’s rest between rounds. “Fair-sized” padded gloves of the “best quality” were to be used, and a downed fighter who failed to arise and come to scratch within the allotted 10 seconds would be considered to have been knocked out. Said contests in all other respects were to be governed by revised rules of the London Prize Ring.

But America was still an evolving and largely frontier nation in 1865, the year the Civil War ended, and such niceties as the Queensberry Rules were seldom applied when two men came together to duke it out with balled fists for purses, side bets and the entertainment of fellow rowdies. Although it was not uncommon for individuals to be regarded as “world champions,” such titles were more the result of public acclamation than of being awarded by a widely recognized governing body. Jim Figg, who reigned from 1719 to 1730, is hailed as the first English bare-knuckle champ and was identified by no less an authority than Jack Dempsey, who came along 200 or so years later, as the “father of modern boxing,” a designation more than a few others have reserved for Corbett.

In any case, Sullivan, the son of Irish immigrants, was cast in the mold of classic tough guys who eschewed fancy steppin’ in favor of brute force. Loud, boisterous and fond of strong drink, he would make his presence known by striding into saloons and announcing that “I can lick any man in the house.” Few patrons were foolish enough to test themselves against the great man, but woe be unto those who chose to trade punches with the Strongboy.

The stocky, 5-foot-10 Sullivan has been described as America’s first athletic superstar and hero, and tales of his prowess eventually took on the trappings of legend. He won the bare-knuckle heavyweight championship with a ninth-round KO of Paddy Ryan in 1882 and he even donned gloves to win the Queensberry title with a six-round decision over Dominick McCaffrey in 1885. Most of his scraps, however, were gloveless and more primal, and he embellished his spreading reputation in old-fashioned slugfests with the formidable likes of Charlie Mitchell and Jake Kilrain.

But as John L. aged, he seemed content to rest on his laurels. He had not defended his title in three-plus years, making good money without having to throw or take a punch while touring in the stage production of a play called Honest Hearts, Willing Hands. He did keep his hand in boxing, in a manner of speaking, by engaging in several exhibitions, but he hadn’t participated in a real fight since July of 1889.

On the other side of the country, Corbett, a San Francisco resident and the personal and stylistic antithesis of Sullivan, was honing the kind of ring skills that hinged more on movement, defense and strategy. A bank teller and college-educated, he spoke proper English and had developed his own ardent following with victories over such notables as Kilrain and Joe Choynski, as well as a draw with Australia’s Peter Jackson, a 61-round test of endurance that lasted four hours. A groundswell for the long-inactive Sullivan to defend his title against Corbett – who turned pro in 1886 and had never been involved in a bare-knuckle fight — began to gain momentum.

As was the case with Sugar Ray Robinson, Mayweather and so many others who came to consider financial compensation for their services to be a reflection of their greatness, Sullivan said he would fight any contender for a winner-take-all purse of $25,000 plus a side bet of $10,000 put up by each man. The winner of Sullivan-Corbett thus would collect $45,000, a king’s ransom when you consider that $100 in 1892 dollars would be worth $2,541.10 in 2016. That meant a payout to the victor that was the equivalent of $1,143,495 in 1892, which might not seem like much to a profligate 21st-century spender like Mayweather, but consider this: the average annual income of U.S. workers in that time period ranged from $370.45 for coal miners to $493.20 for school teachers to $742.69 for plumbers. Also, the buildup for Sullivan-Corbett did not involve the Internet, satellite communications and television. Those who could not attend the fight in person had to make do with telegraph reports sent from the fight site to New York and then transmitted elsewhere around the country.

A momentary problem was that Corbett and his manager, William A. Brady, didn’t have the $10,000 side-bet fee. Corbett’s West Coast backers helped raise the cash in fairly quick order, however, and the fight was on. To appease Louisiana officials anxious to give the much-anticipated affair a veneer of gentlemanly propriety, it was announced the Queensberry Rules would be in effect. Although that stipulation clearly was beneficial to Corbett, Sullivan agreed to it because, hey, he knew he was the one who would come away even richer and more famous. To John L.’s way of thinking, all “Gentleman Jim” was apt to get were lumps, stitches and humiliation.

The big showdown was actually a rematch of sorts. The two had squared off in an exhibition at the Grand Opera House in San Francisco on June 26, 1891, when Sullivan was in town during a theatrical tour. In a departure from his rough-hewn image, John L. decreed that the two men wear formal evening attire, which they did. The action, such as it was, did not remotely hint at the drama that would unfold 14½ months later.

The selection of New Orleans as the host city made sense, and in more ways than one. It was a city that was somewhat renowned as a fight site, beginning with the 1870 pairing of Jem Mace and Tom Allen, considered the first heavyweight prize fight. Not only that, but Sullivan-Corbett, fittingly labeled “The Battle of New Orleans,” was to be the capper of a three-day extravaganza of pugilism heralded as the “Carnival of Champions” from Sept. 5-7. The opening act saw undefeated lightweight Jack McAuliffe extend his winning streak against Billy Myer followed by featherweight titlist George Dixon, a black man, extending his six-year reign with a beatdown of Jack Skelly.

But those bouts were just meant to whet the public’s appetite for Sullivan-Corbett, with the rusty and apparently undertrained John L., a bit fleshy around the midsection at 212 pounds, 25 more than his lithe, perfectly coiffed challenger, nonetheless a 4-to-1 wagering favorite. Demand for tickets was such that event organizers erected temporary seating that raised capacity in the French Quarter facility from 3,500 to nearly 10,000, with ducats priced from $5 to $15, but scalped for much more.

The first two rounds saw Corbett, who did not throw a punch, retreating to the corners, which served the dual purpose of forcing Sullivan to chase him and slowly tire, and for the Californian to time and slip the loaded-up right hand that John L. had so frequently employed to starch a succession of previous victims. Whenever Sullivan let fly with that mighty right, however, it sailed through the empty space that had just been vacated by Corbett.

Even as the crowd grew restless at what many perceived as Corbett’s refusal to stand and fight, boxing as it had been was about to be radically changed forever, with liberal dashes of sweet science added to the standard recipe of pure slugging. In the third round, Corbett caught the bull-rushing champion with a big left of his own, breaking his nose, which bled profusely thereafter.

Corbett continued to stick and move, landing almost at will on an increasingly exhausted Sullivan until the 21st round when John L. twice was floored, and was counted out after the second by referee John Duffy, a local trainer, gym owner and manager with a pristine reputation for fairness.

As the teetotaling, superbly conditioned revolutionary who had just led boxing into a new and improved era, Corbett was celebrating his coronation with friends, family and supporters when the battered Sullivan, who would never fight again, graciously made an appearance at the party to congratulate the winner. The old champ, 33, then bade his farewells and reportedly went on an epic bender to drown his sorrows. A man of voracious appetites, he was 59, in ill health and destitute when he passed away on Feb. 2, 1918. He was a charter inductee into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1990, when a listed record of 40-1-2, with 34 KOs and one no-decision.

And Corbett? He also was a charter inductee into the IBHOF in 1990, but perhaps more so for his role for transforming his sport than for his achievements inside the ropes. He went just 2-4-1 in his seven post-Sullivan bouts, losing his heavyweight title to Bob Fitzsimmons on a 14th-round knockout on March 3, 1897, in Carson City, Nev. Corbett later lost twice to James J. Jeffries twice in bids to regain his title, retiring after the second defeat to finish 11-4-3 (5) with two no-contests.

But Corbett, who was 66 when he died on Feb. 18, 1933, no doubt would have been immensely pleased that his life story, the climax of which was his conquest of Sullivan (played by Ward Bond), was made into a 1942 film, Gentleman Jim, starring the dapper Errol Flynn in the title role. Mike Tyson has long said that that film is his favorite boxing movie.

To comment on this article at The Fight Forum, CLICK HERE.

Check out more boxing news and features at The Sweet Science, where the best boxing writers write.

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Book Review5 days ago

Book Review5 days agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoOleksandr Usyk Continues to Amaze; KOs Daniel Dubois in 5 One-Sided Rounds