Featured Articles

This Title Shot is a Hart-to-Hart Production

As much a political activist as a boxing promoter, Top Rank founder and chairman Bob Arum is providing 500 free tickets for Friday night’s ESPN-televised fight card at the Tucson Convention Center to so-called “Dreamers,” children of illegal immigrants, mostly from Mexico, whose status for remaining in the United States has been called into question by the Trump administration.

“They’re as American as my grandchildren,” says the Brooklyn-born Arum, who often finds ways to combine his business operation with his social-justice agenda.

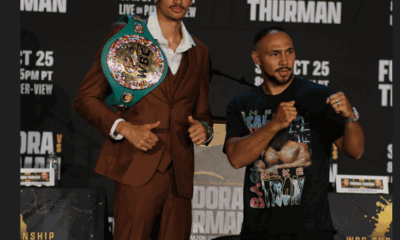

In a manner of speaking, another dream may or not be fulfilled in the co-main event of the TV doubleheader, in which WBO super middleweight champion Gilberto “Zurdo” Ramirez (35-0, 24 KOs), of Mazatlan, Mexico, defends his title against Jesse “Hard Work” Hart (22-0, 18 KOs), the WBO’s No. 1 contender from Philadelphia. But the dream team in this instance is not so much comprised of the Ramirez family as by the Harts, whose long, thus-far-fruitless quest to claim a world championship now rests on the wide shoulders of the 28-year-old Jesse, who has been raised almost since birth to achieve something that his once-world-rated middleweight contender father and trainer, Eugene “Cyclone” Hart, and other assorted relatives could not.

The other co-featured marquee bout pits WBO featherweight titlist Oscar Valdez (22-0, 19 KOs) against No. 4 contender Genesis Servania (29-0, 12 KOs), of Bacolod City, Philippines.

“My family, both sides of it, were brought up with boxing,” noted Jesse, who is co-promoted by Top Rank and Peltz Boxing. “My dad, obviously, but also on my dad’s side were my uncle (Alfred Lowery) and my dad’s uncle (Jimmy Hart) as well as a cousin on my mom’s side (Rick Williams).

“Now I have my own family (manager-wife Starletta and daughter Halo). To bring back that belt to my household would be something I almost can’t describe. It would mean everything.”

Perhaps, if Cyclone Hart had won a world title – or even been afforded the opportunity to fight for one – Jesse’s sense of purpose might not be so clear and defined. But who’s to say? Children born into the Wallenda family are raised from an early age to become high-wire walkers because … well, just because. Sometimes there is no escaping who we are meant to be in life.

“Mentally, I have been prepared for this (to fight for and win a world championship) since I was just a little kid,” Jesse said. “My whole life has been directed toward this moment. My dad showed me tapes of all the great Philadelphia fighters, fighters that became champions of the world or could have been, from as far back as I can remember.

“Now that I’m so close to doing what I have so long prepared for, I can honestly say I’m ready. Of course there’s going to be a little nervousness, but it’s not going to overwhelm me or anything like that. Nothing can or will stop me from performing at my highest level. I’m not going to freeze up. How could I, when I’ve been groomed for this since I was six years old?”

At 6-foot-3 and 168 pounds, Jesse is not a carbon-copy of his 5-11½ father, either physically or even stylistically. He considers himself a boxer-puncher, more capable of winning with a varied attack than was his dad, a legendarily devastating puncher who went into every fight looking to score a knockout, as early and as emphatically as possible. It was a strategy that either worked well or didn’t, as evidenced by Cyclone’s 30-9-1 record, which included 28 knockout victories (18 coming in the first three rounds) and eight defeats inside the distance. Cyclone’s weapon of choice was that Philly favorite, the left hook.

“Jesse’s a good puncher, but he’s not in his father’s league when it comes to pure punching power,” said J Russell Peltz, who promoted Cyclone and now is involved with the son. “I’m just telling it like it is.”

One of a quartet of Philadelphia middleweights who were all world-rated at the same time in the early 1970s – the others being Bobby “Boogaloo” Watts, Willie “The Worm” Monroe and the late Bennie Briscoe – Hart was being talked up as a possible challenger to Argentine great Carlos Monzon when misfortune struck. During a fight with former junior middleweight titlist Denny Moyer on Sept. 21, 1971, at the Spectrum in Philly, both men tumbled through the ring ropes in the sixth round. Moyer suffered an injured ankle and Hart was knocked unconscious after striking his head on the floor, resulting in a no-contest.

Cyclone Hart did not fight again until Feb. 7 of 1972, a second-round knockout of Matt Donovan, but in his next bout after that he was stopped in eight rounds by Nate Collins and any hope of procuring a shot at Monzon vanished.

Might Cyclone have taken out the seemingly invincible Monzon had he landed that vaunted left hook just so? Possibly, although Peltz wonders if that proposed fight ever could have advanced beyond speculation.

“Teddy Brener (Madison Square Garden’s esteemed matchmaker) was trying to get him a title shot late in 1971, but Monzon was not controlled by the Garden, despite of how powerful Teddy was,” Peltz said. “I don’t believe Monzon actually was going to fight Cyclone, who just wasn’t a big enough name internationally. Anyway, that’s as close as he ever got.”

Ironically, the dream matchup that might have gone to Hart instead went to Moyer, who fell in five rounds to Monzon on March 4, 1972, in Rome.

Jesse was not around to witness his dad’s rise nor his fall; he was born on June 26, 1989, 10 days before Cyclone’s 38th birthday and nearly seven years after his final bout. His not-inconsiderable power and some of his moves were passed along by his father, but some of his finer technical points came from another veteran Philadelphia cornerman, Fred Jenkins, the original trainer of 1996 Olympic gold medalist David Reid.

In addition to his dad, of course, Jesse lists Reid as a hero and role model. Jesse was not quite seven when he watched Reid, who was trailing on points, win the gold medal with a turn-out-the-lights overhand right in the final round against Cuba’s Alfredo Duvergel. That punch instilled in Jesse a dream of his own, in which he would go to the 2012 London Olympics and win a gold medal. He admits to feeling crushed when, as the favorite, he missed out on a chance to represent his country by the narrowest of margins, losing on a controversial second tiebreaker in the U.S. National Championships against Cleveland’s Terrell Gausha.

“That still haunts me,” Jesse said. I wanted so much to go to the Olympics and win a gold medal like David Reid. I was bitter about how that all ended for me. But it probably helped me get this far in the pros, and this fast. And besides, my father’s dream for me wasn’t so much about going to the Olympics as it was for me to win a world championship as a pro.”

One thing Jesse apparently does better than his dad is talk. Peltz described him as “a marvelous self-promoter” who, should he get past Ramirez, a formidable southpaw, might stage his first title sometime in the first quarter of 2018 in Philadelphia. Asked for his thoughts on “Zurdo,” Hart gave him short shrift.

“All due respect, but when I look at him I see a boy, not a man,” Jesse said. “I don’t see somebody who thinks on his own. He’s always looking to his corner for instructions. His main weakness is his mind. Everything he does, I’ll have an answer for.”

Ramirez has said Hart “must pay” for such remarks, and that his dream is to shut the challenger’s mouth. Then again, that’s the nature of dreams. Not everyone’s gets to come true.

RIP David Bey

Sometimes the boxing gods dispense or withhold their favors with no particular sense of rhyme or reason. Fringe heavyweight contender Chuck Wepner wangled a dream if ultimately doomed shot at the great Muhammad Ali, registered a knockdown (or maybe it was a trip), thus inspiring Sylvester Stallone to launch the Rocky film franchise, and just this year was portrayed by Liev Schrieber in a movie, Chuck, based on his improbable life. Another fringe heavyweight contender, Buster Douglas, was served up as a sacrificial offering to Mike Tyson in Tokyo, but shocked the world in scoring the biggest upset in boxing history and was rewarded with a $24 million payday in his first and only title defense. Still another fringe heavyweight contender, Randall “Tex” Cobb, became something of a celebrity after losing every minute of every round to champion Larry Holmes and rode that notoriety to some nice movie credits as a craggy-faced tough guy.

Then there’s David Bey, a Philadelphia native whose heavyweight ring career can be likened to, in one way or another, all of the aforementioned passers-by in boxing’s more exclusive neighborhoods. But Bey, who was 60 when he died on Sept. 13 in a construction accident in Camden, N.J., reaped few residual benefits from his brief flirtation with fame and fortune, other than his induction earlier this year into the Pennsylvania Boxing Hall of Fame. Like Wepner, Douglas and Cobb, Bey was granted an opportunity to fight for the IBF heavyweight championship of the world, and he gave a credible account of himself in a 10th-round TKO loss to Larry Holmes on March 16, 1895. Unbeaten at 14-0 with 11 KOs the night he entered the ring against Holmes, Bey’s status as a fighter on the rise quickly flamed out as he lost five of his next six bouts, three inside the distance. There would be no calls from Hollywood, even though Bey had a face that leaned more to handsome than to hammered and he did briefly date Grammy Award-winning singer Natalie Cole, daughter of the legendary Nat “King” Cole.

Unbeaten at 14-0 with 11 KOs the night he entered the ring against Holmes, Bey’s status as a fighter on the rise quickly flamed out as he lost five of his next six bouts, three inside the distance. There would be no calls from Hollywood, even though Bey had a face that leaned more to handsome than to hammered and he did briefly date Grammy Award-winning singer Natalie Cole, daughter of the legendary Nat “King” Cole.

Bey retired with an 18-11-1 (14) record after his final bout, an eighth-round stoppage of David Jaco on Sept. 17, 1994, in Macao, China, whereupon he returned to Philly and a blue-collar life. The guy who managed to get Holmes’ attention with a crisp left hook in the second round of their title fight was a member of Local Carpenters 179, operating a pile driver, when he was involved in the fatal accident.

Informed of Bey’s death, Holmes recalled him as “an awkward fighter” who “gave his all.”

“He could fight. He hit me pretty good” (with that second-round left hook),” Holmes continued.

As for those parallels between himself and other fighters who got a brief taste of heavyweight nectar, the 6-foot-3, 240-pound Bey turned pro on Nov. 6, 1981, with a first-round TKO of, yes, Buster Douglas in Pittsburgh, thus making him a man who beat the man (Tyson), and his Philly roots gave him a kinship of sorts with Cobb, who relocated from his native Texas to Philly to advance his boxing career.

Rest in peace, David.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel.

-

Book Review4 weeks ago

Book Review4 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Debunking Two Myths and Other Notes

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoNikita Tszyu and Australia’s Short-Lived Boxing Renaissance

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoKotari and Urakawa – Two Fatalities on the Same Card in Japan: Boxing’s Darkest Day

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoIs Moses Itauma the Next Mike Tyson?

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoBoxing Odds and Ends: Paul vs ‘Tank,’ Big Trouble for Marselles Brown and More

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 340: MVP in Orlando This Weekend