Canada and USA

The Rise and Fall of Intercollegiate Boxing

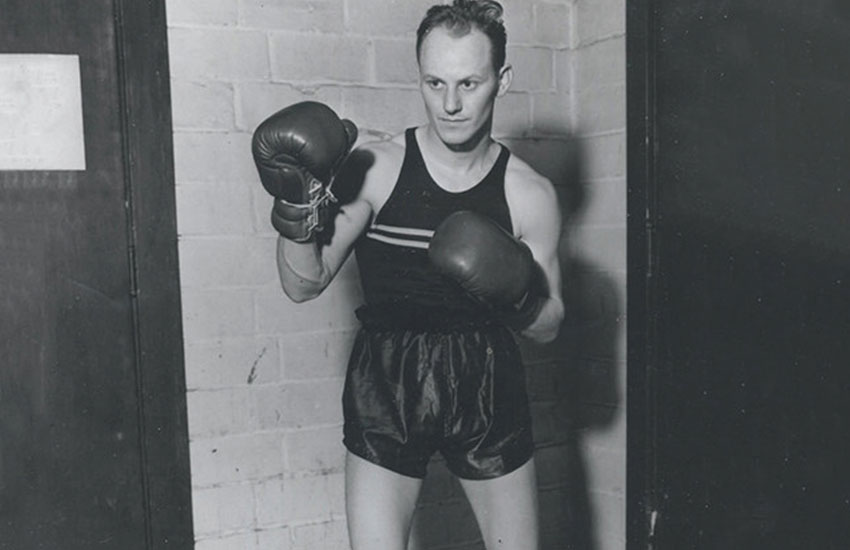

Benjamin “Benny” Alperstein passed away at his home in Chevy Chase, Maryland, on September 16th at the ripe old age of 102. The name didn’t ring a bell but when Alperstein (pictured in his college days) was identified as a former two-time NCAA boxing champion, this reporter was reminded that there once was a time when boxing outdrew basketball at many colleges and universities.

Wearing the colors of the University of Maryland, Battling Benny Alperstein won the NCAA lightweight title in 1937 and the NCAA featherweight title in 1938 when he received the tournament’s Outstanding Boxer award. An Air Force Major during World War II, Alperstein never turned pro but kept his hand in the sport as an administrator and boxing judge. He served 30 years on the Maryland State Athletic Commission and for a time was the chairman of the Washington D.C. commission.

When intercollegiate boxing was in its heyday, college coaches trolled AAU tournaments for fresh talent. There were even reports of recruiting abuses with coaches providing extra benefits beyond a full athletic scholarship to the most promising prospects. (Sound familiar?)

Penn State won the inaugural NCAA tournament in 1932. Within a few years the University of Wisconsin emerged as the dominant program. The Badgers won eight NCAA team titles between 1939 and 1956.

School was out for spring break, but yet 10,322 turned up at the Wisconsin Fieldhouse on April 9, 1960, for the final round of the national tournament. Little did the attendees know that they would be witnessing the death knell of intercollegiate boxing.

Wisconsin co-captain Charlie Mohr, a 22-year-old senior and the defending NCAA 165-pound champion, was knocked out in the second round by San Jose State’s Stu Bartell and collapsed in the dressing room after leaving the ring under his own power. Diagnosed with a brain hemorrhage, he underwent surgery but no avail. A devout Catholic, Mohr died eight days later on Easter Sunday morning without regaining consciousness.

College boxers fought three two-minute rounds with 12-ounce gloves and padded headgear and referees were instructed to stop a contest as soon as it became clear that one man was outclassed. Every precaution was taken to avoid such a calamity, but in the aftermath of Mohr’s death the UW faculty overwhelmingly voted to abolish the sport and the NCAA quickly followed suit. The schools that balked reduced boxing to a club (non-scholarship) sport. (A new governing body for intercollegiate boxing was formed in 1976, but the tournaments held under their auspices are mere blips on the radar screen. Intramural boxing continues to flourish at a handful of schools, notably the service academies and Notre Dame.)

Even before Charlie Mohr’s death, the geography was changing with the sport undergoing a sharp westward shift. In the final years of the NCAA tournament, San Jose State, Idaho State, Washington State, and the University of Nevada at Reno fielded strong programs.

Idaho State spawned two two-time NCAA champions who went on to fight for world titles, albeit unsuccessfully. Ellsworth “Spider” Webb, who was from Oklahoma, got his shot against Gene Fullmer in 1959. Roger Rouse, who was from Montana, challenged light heavyweight champion Bob Foster in 1970. The most notable alumnus of the Nevada program is Mills Lane. The ex-Marine captured the NCAA welterweight title in 1960, was 10-1 as a pro (the loss came in his pro debut), served as the Washoe County (Reno) District Attorney and a district judge, became a prominent boxing referee and then had his own syndicated Court TV-style television show.

Chuck Davey

The only four-time NCAA champion, Chuck Davey became the poster boy for intercollegiate boxing. The sandy-haired southpaw for Michigan State won his first NCAA title in 1943 as a 17-year-old freshman and won three more after returning to school on the G.I. Bill after a four-year hitch in the Army Air Corps. As an amateur, his only defeat came in the finals of the 1948 Olympic Trials when he lost a split decision to future world lightweight champion Wallace “Bud” Smith.

When Davey turned pro, he had trouble finding backers. He wasn’t a big puncher and college boys, let alone southpaws, were taboo.

Those that passed on Davey were myopic. This was 1949 and TV sales were about to skyrocket. Because Davey didn’t fit the stereotype of a prizefighter, viewers were smitten with him. Davey became a star in what is still considered the golden era of TV boxing, an era when a 13-inch black-and-white TV was a prized household possession and a TV repair shop could be found on every town’s main street.

Davey brought a 37-0-2 record into his 1953 world title fight with defending welterweight champion Kid Gavilan at Chicago Stadium. Gavilan, who supposedly had no formal education, having supposedly spent his boyhood wielding a machete in the sugar cane fields of Cuba, gave Davey a boxing lesson. Davey’s corner mercifully threw in the towel after the ninth round. The old salts said “I told you so.”

School of Hard Knocks 1, Michigan State 0

The one-sidedness of the bout produced a backlash. Fight fans carped that Davey was never as good as he was cracked up to be and that coming up the ladder he was steered away from tough opponents so as not to corrode his marketability.

There was a kernel of truth in that, but only a kernel. Davey caught ex-champions Ike Williams and Rocky Graziano at the tail ends of their careers, but two wins over a prime Chico Vejar and another over up-and-comer Carmen Basilio gave evidence that he was legit.

Davey had nine more fights after his mauling by Kid Gavilan and retired with a 42-5-2 ledger. In retirement, he embraced a new sport, long-distance running, participating in marathons into his sixties. He ran a thriving life insurance agency and served several terms as the head of the Michigan boxing commission, more formally the Michigan Athletic Board of Control. More than that, he put boxing in a positive light just by being himself. Whenever the late great trainer Eddie Futch was challenged on the proverb that boxing builds character, he defended his turf by citing the example of Chuck Davey.

In 1998, Davey was paralyzed from the neck down in a swimming accident. He died four years later at age 77. He was survived by his wife, a former nurse, their nine children and 46 grandchildren.

Billy Soose

Before there was Chuck Davey, there was Billy Soose. Recruited by Penn State out of the sooty Pittsburgh suburb of Farrell, Pennsylvania, Soose never won an NCAA title but would have been favored to do so in 1938 if he had been allowed to compete. In January of that year, the athletic conference with which Penn State was then affiliated passed a rule that barred college boxers from competition if they engaged in other amateur bouts. The impetus was a spate of unregulated amateur shows in which the participants, as was common knowledge, were being paid under the table.

With his scholarship lifted, the Penn State captain moved up his timetable for turning pro. In short order, he became one of the most popular boxers in the Keystone State.

Soose turned heads in 1940 when he turned away middleweight champs Ken Overlin and Tony Zale in matches spaced four weeks apart. Overlin, undefeated in his last 22 fights, held the New York State version of the middleweight title; Zale was the more widely recognized National Boxing Association belt-holder. Folks then started calling Soose the uncrowned champion, a tag he shed in May of 1941 when he repeated his triumph over Overlin in a 15-round contest at Madison Square Garden.

Shortly after Pearl Harbor, Soose enlisted in the war effort, relinquishing his title. He served four years in the Navy and never fought again. As a pro, his record was 40-6-1. He never could solve the unorthodox style of Georgie Abrams who outpointed him three times. His other setbacks, all on points, were to journeyman Johnny Duca (a disputed decision) and future Hall of Famers Charlie Burley and Jimmy Bivins.

Soose invested his ring earnings wisely. He purchased 400 acres in the Pocono Mountains where he did much of his training and developed a resort that included a popular restaurant that bore his name. He died in 1998 at age 83.

R.I.P. Joe DeNucci

Former middleweight contender Joe DeNucci, a lifelong resident of Newton, a formerly blue-collar suburb of Boston, passed away on Sept. 8 at age 78. His death, occurring 11 days before the death of a far more celebrated Italian-American boxer, Jake LaMotta, was a significant news story in Boston but attracted nary a mention on web sites devoted to boxing.

The son of a janitor, Angelo Guiseppe “Joe” DeNucci was a Massachusetts Golden Gloves champion at age 16 and turned pro while still in high school. As a pro he was 54-15-4 while defeating such notables as Ralph “Tiger” Jones, Joey Giambra, and Denny Moyer. He had 23 fights at Boston’s fabled Boston Garden and would be credited with keeping the sport alive in Boston following the retirements of ex-champions Tony DeMarco and Paul Pender.

After boxing, DeNucci turned to politics. He served in the state legislature and then six four-year terms as the state auditor, becoming the longest-serving state auditor in the history of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

On paper he was unqualified for the position. He wasn’t a CPA and wasn’t college educated. But he had a natural aptitude for math and a keen eye for waste and fraud. It would be written that he saved the taxpayers of Massachusetts more than a billion dollars during his tenure.

Like all good grassroots politicians, DeNucci was an inveterate joiner. Among other affiliations, he was an active member of Ring 4, the Boston chapter of the Veteran Boxers Association, an organization that provides financial support to ex-boxers who have fallen on hard times. His death was attributed to complications from Alzheimer’s.

Benny Alperstein photo courtesy of the University of Maryland Department of Sports Information.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel.

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Book Review2 weeks ago

Book Review2 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles7 days ago

Featured Articles7 days agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRahaman Ali (1943-2025)

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoTop Rank Boxing is in Limbo, but that Hasn’t Benched Robert Garcia’s Up-and-Comers