Canada and USA

An Unforgiving Minute

BWAA president Joe Santoliquito typed a post on Facebook, “Rigondeaux hurt his left wrist.” Dave Wilcox replied immediately: “I think he hurt his left ego.”

At 11:30 Saturday night, as Guillermo Rigondeaux was surrendering in his corner after the sixth round of his fight against Vasyl Lomachenko, BWAA president Joe Santoliquito typed a post on Facebook, “Rigondeaux hurt his left wrist.” Dave Wilcox replied immediately: “I think he hurt his left ego.”

He skipped the post-fight press conference and headed to a hospital near Madison Square Garden for an examination. He did some soul searching on the way.

Rigondeaux is one of only three legitimate champions in boxing. Light heavyweight king Adonis Stevenson has long-since exchanged his Superman cape for feathers, having spent four years contenting himself with comparative chicken feed—and avoiding Andre Ward, Sergey Kovalev, and anyone else who had half a chance to beat him. Terence Crawford took his first crown in 2014 after defeating the #2 contender in the Transnational Lightweight Rankings, abdicated in 2015, and won the jr. welterweight crown in 2016 after defeating the #1 contender when he was ranked #2. He’s headed to welterweight now to further a reputation that is everything Stevenson’s is not.

Rigondeaux is neither coward nor conqueror. His reign at jr. featherweight began with promise after he outclassed then-champion Nonito Donaire but soon stalled out. Since then he has defended bouncy castle with pool his crown six times. Five of those challengers were not ranked at jr. featherweight and four of them were not ranked at all and never had been.

One problem is the people around him. Caribe Promotions, a Miami-based outfit, has proven both a hindrance to Rigondeaux’s progress and a hardship to work with if the departure of co-promoter Top Rank and manager Gary Hyde and a lawsuit filed against Roc Nation are any indication. Caribe’s Twitter accounts have been inactive for two years and a Facebook page has five likes. Google their website and you’ll see a warning that it might be hacked.

Another problem has been the champion’s woeful marketability. Rigondeaux’s economical and evasive style makes him the Anti-Gatti and that’s no way to earn a following in a combat sport, especially in this ADD era. Top opponents see serious risk and slight reward and have diligently avoided him. It’s hard to blame them. Carl Frampton’s hand was barely raised after he defeated Leo Santa Cruz when Rigondeaux tweeted his willingness to face him: “I am available to travel to your hometown.” Frampton admitted the offer came from “an unbelievable fighter” and turned him down. “He doesn’t bring any money to the fight,” he said. In June of this year Rigondeaux faced his only undefeated challenger thus far in Moises Flores and his purse was a lousy $120,000. Last year he earned about as much as a union plumber.

He earned $400,000 Saturday night, though Bob Arum made sure it was three times less than what Lomachenko took in.

Even so, it was Rigondeaux –underpaid, physically overmatched, and past prime– who won the first round. His reach was put to good use, he actively adjusted his distance to keep Lomachenko where he wanted him, and he landed a few lefts to the body.

The tables were turned in the second round. Lomachenko saw every tactic Rigondeaux relied on and swiped left.

He saw Rigondeaux’s hope of stunting his sorties with a jab and dashed that hope by neutralizing Rigondeaux’s reach, the only physical advantage he had. He did it with ease; his jab outlanded Rigondeaux’s despite relatively stubby arms because of his ability to dart in at different angles, land one, two, or three of them in rapid succession, and slide out.

He also turned Rigondeaux’s habit of bending deeply to his left into a liability. He understands how to exploit that position—scoop him with right uppercuts and rain down punches on the side of his face or the back of his head.

He doubly foiled Rigondeaux’s plan to clinch at close quarters. Rigondeaux’s purpose with this tactic was to steal a moment to rest and get a moment to reset, but for that to work the referee would have to be recruited as an assistant; an assistant who would either let him clinch or actively break it and allow an escape. Rigondeaux didn’t know Lomachenko had already alerted referee Steve Willis in the dressing room and even practiced his countermove with him. The result was apparent in that second round: Lomachenko, mindful of Willis’s restrictions, wrenched free of the clinch and immediately disciplined Rigondeaux with a right and a left. Alarmed, Rigondeaux looked to Willis and was ignored. The next time they clinched, Willis told them to work out of it and Rigondeaux threw up the point of his right elbow, clearly intending to connect on and perhaps cut Lomachenko about the eyes. Willis didn’t see it; Lomachenko did and smirked. Rigondeaux’s feigned apology was followed up by headlocks and another illegal tactic—holding and hitting. Desperation had set in.

Rigondeaux didn’t really win the first round despite what the scorecards said. Lomachenko casually lost it so he could gauge Rigondeaux’s assets and warm up. It was all he needed to steal away Rigondeaux’s reach advantage and jab, turn his left-leaning defense into a liability, and solve the clinch.

So what was left for Rigondeaux to do? What do we do when faced with desperate circumstances and unforgiving minutes? We scan the landscape in search of something missed or a magic bullet. We toss up a few Hail Marys and hope for the best. We loosen up our principles a little more than we otherwise would. Rigondeaux tried in vain to find a way to change his fate. He threw a few overhands and hooks and uppercuts that missed or had zero effect. At the end of the fifth round, he tried to wrench Lomachenko’s neck in a headlock. In the sixth, he was aiming punches at his groin and was ignoring Willis’s warnings about clinching every time the Hi-Tech tormentor closed in. Nothing worked. When Willis deducted a point from him for excessive holding, he felt like anyone who steps on the accelerator with the gear left in reverse. His exertions were having a negative effect, which diminishes the spirit.

The sixth round hadn’t quite ended when Lomachenko began walking back to his corner, leaving Rigondeaux to stand and wait and wonder. The bell clanged, snapping him out of the moment and sending him to his minute’s rest. He sat down, looked at his hands, and saw he had nothing.

What could he do? When hope is gone and the seconds seem like hours, what do we do? We look for a way out; at times we immolate ourselves.

He told his trainer his left hand was hurt and he couldn’t continue. And just like that a thirty-seven-year-old phenomenon who boldly jumped up two divisions to face boxing’s most perfect fighter, who made one last grab for glory, quit on his stool. It won’t matter whether his hand was broken, bruised, or underused; in an era where the town crier never sleeps and his platform is worldwide, Rigondeaux’s decision has dire consequences. And despite the heroism of his escape from tyranny, the memory of a family left behind, the glory of his gold medals and his ascension to the heights of his profession in the land of plenty, that decision will carve a corner in his mind. It will haunt him for the rest of his days.

Vasyl Lomachenko was just beginning to acknowledge his victory when someone put a crown on his head. He was honest enough to take it off. He’ll have to face the next-best contender in the division to earn a true crown, though the hope is he’ll move up to lightweight and face the top-two contenders one after another and raid his way into a succession alongside Duran and Whitaker, Armstrong and Canzoneri. If the all-time greatness his father promised “before he was conceived” is his objective, then he’ll know that in boxing, it is not reflected in the accolades of excitable commentators and it cannot be bought with sanctioning fees siphoned off his purses. Greatness is determined after a fighter’s deeds and adventures are examined in the light of comparative history, of actual history, where the claim that he is already a “two-division world champion” is dismissed as a lie. Look for Lomachenko to laugh off the belts and pursue every premier fighter within reach.

Guillermo Rigondeaux, as forlorn as Lomachenko is forthright, has only the shadows to contend with now. When hope is gone and the seconds seem like hours, what do we do? We look for a way out; at times we immolate ourselves. In boxing they’re one and the same.

Only minutes after he left the ring, a tweet appeared on the @RigoElChacal305 account. “There is only one thing I can say,” it said. “‘I AM SORRY’.”

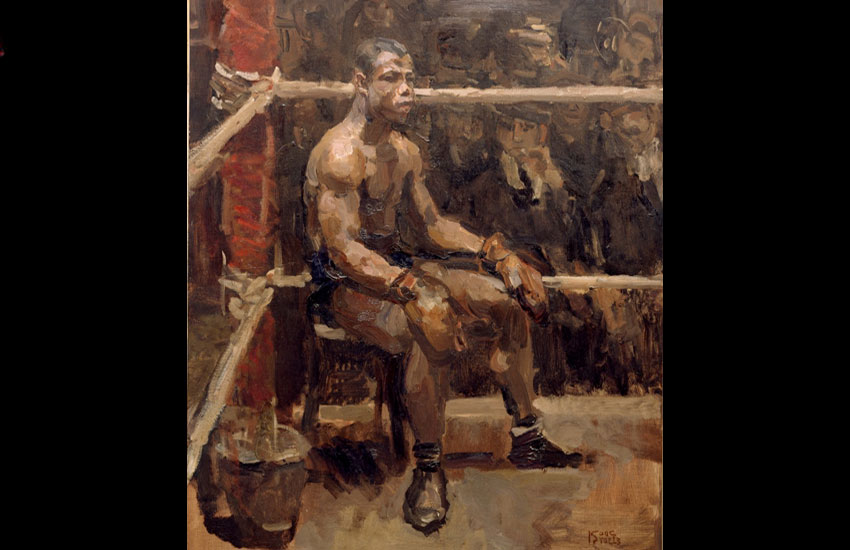

“Negro Boxer” by Isaac Israels, 1914-1915

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel.

To comment on this article at The Fight Forum, CLICK HERE.

___________________

Springs Toledo is the author of The Gods of War (Tora, 2014), In the Cheap Seats (Tora, 2016), and Murderers’ Row (Tora, 2017). Autographed copies available at www.SpringsToledo.com

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Book Review2 weeks ago

Book Review2 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles6 days ago

Featured Articles6 days agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRahaman Ali (1943-2025)

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoTop Rank Boxing is in Limbo, but that Hasn’t Benched Robert Garcia’s Up-and-Comers