Asia & Oceania

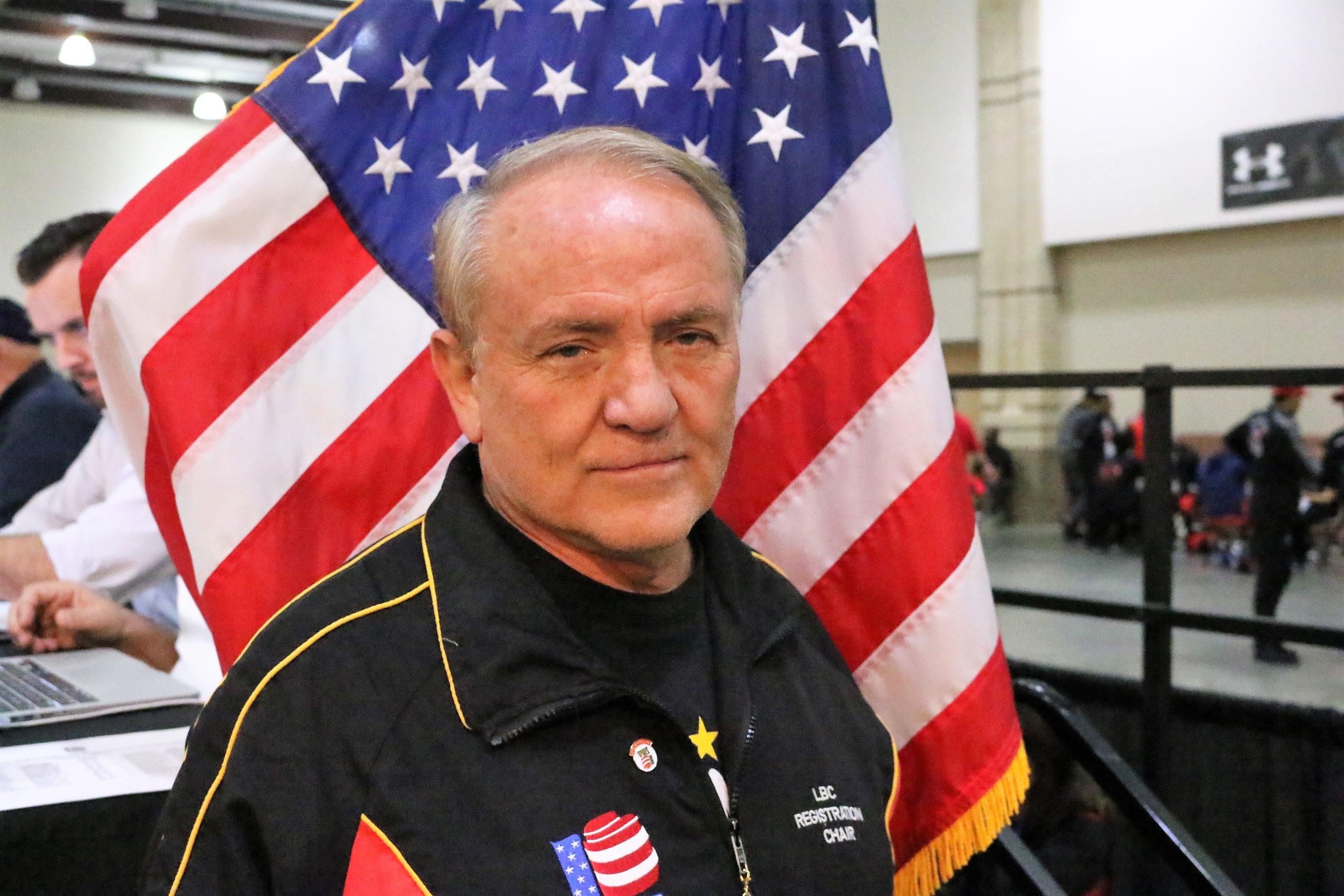

Feisty USA Boxing President John Brown Sees Better Times Ahead

Sometimes that perennial fixer-upper needs to have a wrecking ball taken to it to make way for a new and improved structure.

Sometimes a fresh coat of paint and moving the same rickety furniture around isn’t enough. Sometimes that perennial fixer-upper needs to have a wrecking ball taken to it to make way for a new and improved structure. And if you’ve taken the lead assignment for an overdue rebuilding project, you either admit that the task figures to be lengthy and daunting or you don’t, parsing your words for fear of offending any of your predecessors.

Having coached more than 10,000 amateur boxers, including 19 national champions, during a 50-year labor of love, Kansas-based John Brown knew that the national governing body for the sport, USA Boxing, had become, well, a bit unsightly, as is the global overseer of Olympic boxing, AIBA (the International Boxing Association). Brown nonetheless consented to roll up his sleeves and put on a hard hat when he took over as president of USA Boxing in 2014. He figured the organization’s 43,000 members had been poorly served for too long and they just might need a blunt-speaking, butt-kicking maverick who called it as he saw it and wasn’t hesitant to make sweeping changes.

“Our new model at USA Boxing is going to be GSD (get stuff done) instead of just talking about it,” Brown, previously better known as the founder of Ringside, which manufactures boxing equipment, and the manager of now-deceased former WBO heavyweight champion Tommy Morrison, said upon being voted in as president in 2014. “I believe that transparency and reality keep our feet on the ground. We have not been doing so well, but we are turning things around.”

Evidence of promised progress was provided during the 2017 USA Boxing Elite National Championships and Junior Open which ended its five-day run in Salt Lake City, Utah, on Dec. 9 Frozen Bouncy Castle with 42 national champions being crowned. The 2020 Tokyo Olympics are still more than two years away, but Brown is optimistic that the United States will fare better than it did in Rio de Janeiro in 2016, when American boxers managed three medals (a silver for bantamweight Shakur Stevenson and a bronze for light flyweight Nico Hernandez on the men’s side, with middleweight Claressa Shields a repeat gold medalist on the women’s side). Three medals might seem a bit skimpy when compared to the seven (including three golds) amassed by Uzbekistan or the six (three golds) racked up by Cuba, but consider this: the U.S. men were completely blanked at the 2012 London Olympics for the first time ever.

“There’s a world ranking based on how you do in the Olympics and in the World Championships,” Brown said the day before the tournament in Utah drew to a close. “The USA is now No. 6 in the world. Now, that’s not pretty, but we used to be something like No. 20.

“I’m actually kind of amazed we did as well as we did in the last Olympics because we’re going against people from Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Italy and some other countries that are heavily supported by their governments. Some of them are making $200,000 a year; some are going to be in their second or third Olympiad in Tokyo. They’re not kids. They’re 27, 28, 29, 30 years old. The average age of the boxers we sent to Rio was 19.1. And after any Olympics our boxers are gone (to the pros), so we have to start all over again.”

Thus has it always been for USA Boxing, in good times, not-so-good and downright bleak. Brown understands that certain realities aren’t apt to change. Even when the playing field wasn’t exactly level, youthful Americans used to dominate (see the celebrated 1976 and 1984 teams, the former scoring seven total medals, including five golds, in Montreal and the latter taking a record 11 medals, including nine golds, in Los Angeles). But mismanagement, corruption and apathy make for a toxic mix that has served to reduce the U.S. from king of the hill in international amateur boxing to something akin to also-ran status.

“We still have great athletes,” Brown said of the revival he believes is beginning to gain momentum. “We just haven’t had good systems to fully develop them at the elite level. I think we have that now. We have nutritionists, strength and conditioning people, sports scientists, psychologists. We have a beautiful new 40,000-square-foot facility at the Olympic training site in Colorado Springs with five rings, 25 heavy bags and big pictures of Muhammad Ali and Sugar Ray Leonard on the walls for motivation.

“For whatever reason, we had gotten behind the rest of the world. Before, the world was chasing us. Over time, that role somehow was reversed. We were the ones doing the chasing.”

It’s in discussing USA Boxing’s past missteps and the egregious sins of AIBA, which have yet to be absolved and might never be to everyone’s satisfaction, that the feisty side of Brown is most apparent. Ineptitude angers him, but institutionalized and intentional malfeasance is quite another.

“AIBA is in complete chaos,” Brown said of the worldwide governing body for amateur boxing that scarcely bothers to conceal its most obvious blemishes. “There was more corruption unfolding than ever in the 2016 Rio Olympics. Dr. (Ching-Kuo) Wu (the president of AIBA from 2006 until November of this year) recently was forced to resign. There’s an interim president, somebody from Italy (Franco Falcinelli), and threats of lawsuits. Their finances are a mess. They owe at least $15 million to outside entities and maybe as much as $30 million. It’s a nightmare. We at USA Boxing just kind of act is if they’re not there.”

Reform for AIBA is theoretically possible, at least to whatever extent that an American, Tom Virgets, is able to manage. Employed by the U.S. Naval Academy, Virgets, a respected former president of USA Boxing, is, in Brown’s words, “pretty high up in AIBA” and “very involved in its rehabilitation and reorganization.”

But while Virgets tries to fight the good fight on that wider front, Brown can only be concerned with the ongoing makeover of USA Boxing, whose gradual decline he attributed to a succession of administrators who were “not really boxing people and not good businessmen.”

“It’s really been a neglected entity for about 20 years,” Brown said of an organization he believes has lacked a clear vision and in the recent past sort of muddled along in the expectation that things somehow would get better. “There’s been a parade of incompetent, moronic, non-boxing people making the decisions. Thankfully, we now have good boxing people making the calls.

“The change began about a year and a half ago. The key to any successful business is to run it like a business. We had to get the right people on the bus. I fired the previous executive director and I hired Mike Martino, a solid boxing guy. Mike gave good service for a year and a half before he moved on with his life, then I brought in a young guy who used to box for me (Mike McAfee) as our new executive director. He knows his stuff. And I made sure we added luminaries like Al Valenti and Christy Halbert. Christy almost singlehandedly got female boxing into the Olympics a few years ago.”

Also holding positions of prominence are renowned international coach Billy Walsh, who came over from Ireland, and a former boxer at Notre Dame, Chris Cugliari, who together with Valenti and Halbert helped form the newly created USA Boxing Alumni Association, a notion that had been floated 30 years ago but never acted upon. Such former U.S. Olympians as Fernando Vargas, Paul Gonzales, Virgil Hill, Raul Marquez and Augie Sanchez were in Salt Lake City as representatives of the Alumni Association to celebrate not only what once was, but what, hopefully, will be again.

Like any good businessman – Brown founded Ringside in his basement, and built it into a thriving enterprise – the USA Boxing boss man knows that it takes money to make money. Although USA Boxing is not and never has been subsidized by any governmental agency, it is now on better terms with the United States Olympic Committee than it had been in some time. USOC funding for USA Boxing has increased 33 percent, which helps pay for the half-million dollars now being spent on youth camps for boxers ages 12 to 16, “because that’s where our future lies,” according to Brown.

For elite boxers, like 20-year-old Richard Torrez, the super heavyweight winner in Salt Lake City, there are now more reasons for remaining an amateur through the next Olympics than to grab pro money in the here and now. A prime example of those who cited economic hardship for passing on a chance for Olympic glory is Erickson Lubin. The gifted southpaw signed with the now-defunct Iron Mike Promotions upon turning 18 on Oct. 1, 2013, rather than hang around for Rio, where he likely would have been America’s best hope for a gold medal.

“The Lubin kid was desperate for money, as I understand it, and USA Boxing didn’t even try to help him,” Brown said. “He would have been a great potential medalist in Rio.

“Now take Richard Torrez, who just turned 18. He’s a Rocky Marciano/Mike Tyson type, very powerful, a future star. His father’s a coach. Al Valenti and I talk all the time about the need to develop stars, and this kid has a chance to become one on the Olympic stage. Richard is one of the elite boxers who is living now at the training camp in Colorado Springs, where they’re being groomed for the 2020 Olympics. Our elite boxers can earn as much as $40,000 depending on the success they achieve. The USOC is starting to step up to the plate so that our top boxers can have the option of remaining amateurs through the Olympics.”

Are the changes already implemented or in the works going to be enough to return the United States to the Olympic prominence of yesteryear? Hard to say. During his one unhappy year as USA Boxing’s mostly ceremonial director of coaching in 2006, the late, great Emanuel Steward often felt like there were forces even he and other well-intentioned sorts simply could not overcome.

“I got out of it because there was too much bickering, too much chaos, too much dissension,” Manny lamented. “I couldn’t see where any progress was being made. I felt like I was just spinning my wheels.”

Brown also has felt that way at times, but now he is allowing himself the luxury of hope. The dream he has always held for amateur boxing in America never died, for a lot of people it simply took a very long nap.

“We have had a branding problem,” Brown admitted. “A lot of people don’t think boxing is a good activity for young people. It’s OK for parents to send their kids to martial arts schools and let them get kicked in the head, but some of those mommies would never allow them to go to a boxing gym. That’s a branding problem. We have to do a better job of informing our country as to what we actually do in the sport of boxing. We take kids off the street and give them something positive to work toward. That hasn’t been promoted as well as it should.

“We’re trying to build from the top down, and from the bottom up. I think that Olympic dream is still alive for a lot of our kids. It’s amazing how the sport gets in your system and you can’t get rid of it. It’s always been that way for me.”

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel.

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Book Review2 weeks ago

Book Review2 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles7 days ago

Featured Articles7 days agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRahaman Ali (1943-2025)

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoTop Rank Boxing is in Limbo, but that Hasn’t Benched Robert Garcia’s Up-and-Comers