Argentina

Fantasy Fisticuffs: The Late Edwin Valero vs. Vasyl Lomachenko. Who Wins?

Coulda, shoulda, woulda. It is the stuff dream fights are made of. What would have happened had Jack Dempsey fought Rocky Marciano, prime on prime

Coulda, shoulda, woulda. It is the stuff dream fights are made of. What would have happened had Jack Dempsey fought Rocky Marciano, prime on prime? Or a Smoke and Iron pairing of Joe Frazier vs. Mike Tyson? Muhammad Ali against three-time Olympic champ Teofilo Stevenson? Sugar Ray Robinson vs. Sugar Ray Leonard from the deliciously rich, high-calorie dessert menu?

The possibilities are endless. How any of us imagine the outcomes is, of course, a matter of speculation, personal flights of fancy that might be 180 degrees different than the opinion held by a neighbor, relative or the guy sitting on the bar stool next to you at your favorite watering hole.

In many instances the fantasy matchups are forever theoretical because the would-be participants are from well-separated eras, and if they weren’t, their best years did not intersect. Others involving contemporaries failed to become reality for various reasons, which is why we never saw Riddick Bowe share the ring with Tyson, his Brooklyn homeboy, or as a pro with Lennox Lewis. Larry Holmes still mentally mixes it up with George Foreman in an oldies-but-goodies clash that never got off the drawing board.

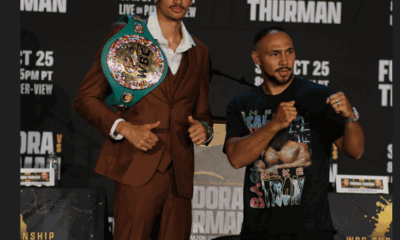

Fight fans that focus on the possible instead of the impossible are doing a lot of theorizing these days when it comes to WBO super featherweight champion Vasyl Lomachenko. If “High-Tech” moves up to lightweight or maybe even higher, as seems likely eventually, will he get it on with Top Rank stablemate Terence Crawford? (Unlikely, at least in the immediate future; Crawford, now the undisputed junior welterweight champ, seemingly is committed to his own step up, to 147 pounds.) How about similarly intriguing showdowns with Mikey Garcia or Jorge Linares?

For purposes of this story, however, let’s play another round of what-if, and the proposed opponent is someone whose meteoric rise to superstardom was cut short by tragic circumstances, some of which were of his own doing and some which perhaps owe to reasons beyond his control.

Golden Boy Promotions president Eric Gomez, for one, holds firm to the belief that the late Edwin Valero, the Venezuelan knockout artist who won all 27 of his pro bouts by knockout, the first 18 of which came in the first round, not only could defeat Lomachenko, but would lay him out.

“Oh, it wouldn’t be that competitive a fight,” Gomez replied when asked to weigh in on a stylistic delight that never can happen, but would have been cause for debate if it ever could have been made. “Valero would knock Lomachenko out. Valero was a truly special fighter, a special talent. He was very, very strong. He had raw power, incredible power, and in both hands. If he hit you, you were out of there, and he hit everybody. Every fight a win, every fight a knockout.”

Like Tony Ayala Jr., whom the late Lou Duva insisted would have been as good or better than the 1980s Big Four of Leonard, Roberto Duran, Marvelous Marvin Hagler and Thomas Hearns had not “El Torito” not lost his prime to drugs, impulsive, destructive behavior and a long prison stretch, Valero’s otherwise praiseworthy career – he held titles at super featherweight and lightweight, in addition to his unbroken knockout streak – has not apparently negated his many out-of-the-ring missteps. For high crimes and misdemeanors in his personal life, Valero in death remains a virtual pariah to many, better forgotten than feted.

Neither Valero nor Ayala — who did 17 years hard time after been found guilty of a brutal sexual assault — have ever been on the ballot as candidates for induction into the International Boxing Hall of Fame, although the IBHOF’s hallowed walls are not exclusively reserved for choirboy types. The late Sonny Liston passed muster in Canastota, N.Y., despite having been arrested 19 times, including a couple of felonies, and an inductee whose life and career track closely parallels Valero’s, the superb Argentine middleweight champion Carlos Monzon, was convicted for murdering his wife in 1989 and yet was a charter inductee into the IBHOF a year later. Like the 28-year-old Valero, who hung himself in his jail cell on April 19, 2010, one day after being arrested for suspicion of murdering his wife, Monzon died relatively young, at 52, on Jan. 8, 1995, in a car crash while on furlough from prison.

Official immortalization for Monzon and permanent scarlet letters of shame for Valero and Ayala might suggest a double standard on the IBHOF’s part, but in any case there are no etched-in-stone criteria which spell out who is or isn’t eligible for consideration. The Baseball Hall of Fame in nearby Cooperstown, N.Y., for instance, has forever banned gambling-tainted Shoeless Joe Jackson and Pete Rose, whose statistics are more than Hall-worthy, but suspected if verifiably unproven steroid abusers such as Barry Bonds, Mark McGwire and Roger Clemens remain on the ballot, if nebulously, un-enshrined but with ever-climbing vote totals.

The IBHOF’s lack of specific do’s and don’ts are troublesome for Kevin Iole, of Yahoo!Sports, but his favorable impressions of Valero are as indelible as those shared by Gomez.

“If you haven’t seen Valero, think of a young Mike Tyson … The Venezuelan fights with a fury,” Iole wrote in 2007. “Remember Tyson’s famous quote about wanting to drive his opponent’s nose into his brain? That’s the kind of fighter Valero is.”

“I don’t know if what he did should preclude him from consideration for the Hall of Fame,” Gomez said. “What I do know is this: he certainly was a great talent and there’s no telling how far he would have gone in his career had things not happened the way they did in his personal life. The crime he committed probably does outweigh his accomplishments in the ring. It’s a good question because it’s open for debate.

“We – Golden Boy – worked with him when he first came to the United States. I made something like five of his matches, until we found out he had had brain surgery in Venezuela.”

Valero, a three-time Venezuelan national champion as an amateur, was raised in poverty on the gang-controlled streets of his hometown of Merida. He was fleeing from police on a stolen motorcycle when it crashed on Feb. 5, 2001, leaving the helmetless driver with a fractured skull and necessitating an emergency operation to remove a blood clot. Nineteen months later Valero, having been cleared to fight in his home country, turned pro with a first-round blowout of Eduardo Hernandez. His reign of terror inside the ropes had begun.

As opponent after opponent failed to make it out of the opening round, Valero, by now managed by Oscar De La Hoya’s father, Joel Sr., came north under the auspices of Golden Boy to make himself better known to American fight fans. But would his run of quickie stoppages continue against a better grade of competition? Even Gomez wasn’t sure that would be the case.

“I put him in with a couple of decent guys and he knocked them out in the first round, too,” Gomez continued. “I then matched him with a veteran fighter from Colombia, Roque Cassiani, who was known for having a really good chin. Cassiani was as tough as nails. I figured there was no way Edwin could take him out in one round. But Edwin flattened Cassiani, and fast. I mean, the guy was out. That’s when I told myself, `We got something special here.’”

The plan called for Valero to reach a wider audience in New York, in the main event of Golden Boy’s Boxing Latino series. This time it was Valero that was kayoed, by a more comprehensive medical exam than he had received for his three fights in California.

“I remember telling Kery Davis (then a senior vice president of HBO Sports), `We got this kid, he’s incredible, he’s going to be a world champion,’” Gomez recalled. “Edwin had passed all the tests he had taken in California, but in New York you had to take an eye test, an MRI, an EKG. I mean, everything. We didn’t expect any problems there.

“Then I get a call from the commission physician, Dr. (Barry) Jordan. They had recently had a tragedy there with a fighter (Beethaeven Scottland) who died after an ESPN fight on a battleship (actually a World War II decommissioned aircraft carrier, the U.S.S. Intrepid, docked in New York Harbor), so there was a lot of scrutiny on the boxing medicals. Dr. Jordan told me, `Edwin Valero didn’t pass his MRI. He has a hole in his head. There’s a part of his skull that’s missing. In my opinion, this kid should never fight again.’”

Gomez sent Valero for another MRI at a facility unrelated to the commission and the result was the same. “I went to Edwin’s trainer and he told me the kid didn’t want to say it, but had brain surgery in Venezuela a few years earlier. We released him because, really, what choice did we have? If he’s suspended in New York, he’s not going to get licensed anywhere else in the U.S., including California.

“Edwin tried to get reinstated in the U.S. for two years, but it wasn’t going to happen. Not then, and probably never. He went back to Venezuela and later was signed by Mr. (Akihiko) Honda, who brought him to Japan where he was allowed to fight. I don’t know how he got cleared there, but he was, and he won a world title (on a 10th-round TKO of WBA super featherweight champ Vicente Mosquera on Aug. 5, 2006, in Panama City, Panama) and retained it three times.”

Moving up to lightweight, Valero won the vacant WBC title on a second-round stoppage of Antonio Pitalua on April 4, 2009, in Austin, Texas – he was licensed in that state on March 25, 2008 – and defended it twice before he was arrested on suspicion of murdering his wife, Jennifer Carolina Viera de Valero, in a hotel in the Venezuelan city of Valencia. She had been stabbed three times. Valero understandably was an immediate suspect, having been arrested before on alleged assaults of his wife, mother and sister.

Was Valero’s lack of impulse control, which served him so well as a fighter, caused, at least in part, by the head injury he incurred in 2001? It is a question without a conclusive answer as he also had been a relentless aggressor as an amateur.

“I’ve thought about that,” Gomez said. “If you’re missing part of your skull and you’re getting hit in the head, not just in fights but in sparring, it has to affect you somehow. Some of the stories I heard toward the end from people who were close to him made it sound like he became, I don’t know, paranoid or schizophrenic. He’d say he thought he was being followed, that people were following him. It’s not normal.”

So, could Valero’s power have been a match, or more, for Lomachenko’s precision? If a poll were being conducted today, the likely consensus would be that Loma, already hailed as a master of his craft and with the likelihood to continue to add to his legacy for years to come, would have bewitched and bewildered Valero just as he has most everyone else he has faced. Then again …

“Edwin Valero could have been great,” Gomez reiterated. “The sky was the limit for him. We’ll never know just how great he could have been, and the same goes for Tony Ayala Jr.

“I’ve always believed that punchers are born, not made. It might have to do with quick-twitch muscles, like some people say. But for whatever the reason, Edwin was a natural-born puncher. It’s a gift, and it isn’t always about who has the biggest muscles. There are a lot of skinny guys who were terrific knockout artists. Tommy Hearns was one. Alexis Arguello was another.”

TSS’ resident fight analyst, Frank Lotierzo, weighed in on the Lomachenko vs. Valero hypothetical, and although he’d go with Loma, he didn’t discount the possibility of Valero, who would always have a puncher’s chance against anyone he was in with.

“I think so,” Lotierzo said when asked if Valero might have been able to pull off the upset. “I think Lomachenko is magnificent. He’s brilliant. He’s definitely a special fighter, although I think the praise being heaped upon him now might be a little premature. What don’t we know about the guy? We don’t know how he can take a big punch because he hasn’t really been hit by one. We don’t know how he could recover if he gets knocked down or cut. For anybody to think that’ll never happen to him, that’s crazy. We saw Tyson and we saw (Roy) Jones, and during their primes it seemed like they might never lose. So what happens? We found out that Tyson didn’t handle adversity well and Jones doesn’t have a first-tier chin.

“We still don’t know any of that about Lomachenko. He could make Valero look bad because he’s a much better boxer, but Valero might catch him with that big shot because he had major power. Nobody’s ever seen Lomachenko really cracked as a pro.”

So there you have it, TSS Nation. Let your imaginations run wild and weigh in with your opinions.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel.

-

Book Review4 weeks ago

Book Review4 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Debunking Two Myths and Other Notes

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoNikita Tszyu and Australia’s Short-Lived Boxing Renaissance

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoKotari and Urakawa – Two Fatalities on the Same Card in Japan: Boxing’s Darkest Day

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoIs Moses Itauma the Next Mike Tyson?

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoBoxing Odds and Ends: Paul vs ‘Tank,’ Big Trouble for Marselles Brown and More

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 340: MVP in Orlando This Weekend