Canada and USA

The “Lone Star Cobra” Was Special But Didn’t Fulfill His Vast Potential

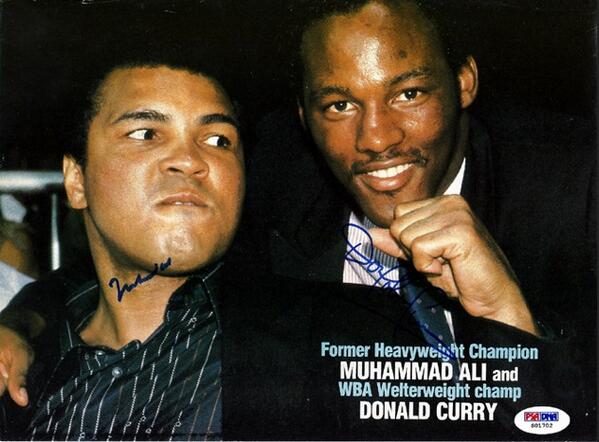

When Donald Curry, the “Lone Star Cobra,” was at his best, which was exceptionally good, he gave no thought of someday being inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame because no such place then existed. The IBHOF officially opened its doors on June 10, 1989, and its first induction class was enshrined exactly one year later, both momentous occasions in the picturesque, central New York village of Canastota predating Curry’s two world championship reigns.

But Curry is now 56, retired and largely forgotten, except as a wistful figure that stood on the precipice of greatness and, for reasons that make sense only to him, found a way to leave unfulfilled the vast potential that once portended sustained success.

On the very night of his career highlight, his two-round demolition of Milton McCrory in their welterweight unification showdown at the Las Vegas Hilton on Dec. 6, 1985, HBO analyst Larry Merchant spoke for many in predicting the brightest of futures for the WBA and IBF welterweight champion, who in short order would violently snatch McCrory’s WBC belt.

“Milton McCrory (then 27-0 with 22 KOs) is a champion, and champions are hard to beat,” Merchant told his HBO viewing audience. “And he’s unbeaten, and an unbeaten fighter is hard to beat. His hit-and-run tactics just might neutralize Curry. If he were to give Curry the fight of his life, it wouldn’t register on the Richter Scale as a major shock. Yet the bottom line on the (betting) line is this: McCrory is regarded as a good fighter. Curry is regarded as possibly a great fighter.”

Greatness seemed to be more than a mere possibility for Curry, a 24-year-old boxer-puncher from Fort Worth, Texas, as he swiftly demolished McCrory, a tall and gangly Kronk Gym stablemate and stylistic approximation of the more celebrated Thomas Hearns.

The first round wasn’t half-over when Curry wobbled and hurt McCrory with a ripping left hook that sent him reeling back into the ropes. Although McCrory somehow made it to the bell, his prospects of surviving long enough to make a real fight of it were quickly dashed. Curry went after his fellow 147-pound titlist as if he were a tiger pouncing on a slab of raw meat. Another left hook upstairs sent McCrory crashing to the canvas and, although he beat the count, he was like a man on the deck of a ship tossed on a turbulent sea. Seconds later Curry connected with a crushing overhand right to the jaw that put McCrory flat on his back, his eyes glazed and unfocused. Not that it was necessary, but referee Mills Lane went through the formality of a 10-count. He could have counted to 50 and McCrory still would have been prone.

With that scintillating performance, there were more than a few knowledgeable fight people who were prepared to anoint Donald Curry (then 26-0, 21 KOs) as the finest pound-for-pound fighter on the planet. Truth be told, Curry held a similarly exalted opinion of himself.

But at the apex of a boxing life that seemed poised to take off like a NASA moon launch, Curry made the most basic and foolish of mistakes. He began imagining all the high-prestige, big-money fights that soon would be coming to him as his just due, instead of paying serious attention to any other truly dangerous opponents, if less renowned, he might face.

That reckoning would not be against Roberto Duran, Sugar Ray Leonard, Aaron Pryor or Hearns, all of whom Curry had envisioned as stepping stones on his way to ring immortality, not to mention the guaranteed seven-figure paydays he perceived as the most legitimate certification of superstardom. It would be against an undefeated Englishman by way of his native Jamaica who should not have been taken lightly, but whom Curry mistakenly thought of as a mere speed bump instead of the presumably more imposing hurdles he already had begun mentally preparing to clear.

After summarily disposing of the outclassed Eduardo Rodriguez in two rounds in his first post-McCrory title defense, Curry was next paired with top-ranked Lloyd Honeyghan (then 27-0, 17 KOs), in a bout scheduled to take place on Sept. 27, 1986, at Caesars Atlantic City. Some observers – mostly those from the United Kingdom – saw Honeyghan as a live underdog. A dismissive Curry figured otherwise.

“I fought off of motivation,” Curry said when contacted for this story. “If I thought that you were a real threat to my career, I’m going to work my butt off to get ready to fight you. That guy, all I knew is that he was named Honey something. I didn’t really know who he was. After the Milton McCrory fight, I was looking for something bigger and better. That was my attitude.

“They told me he was ranked No. 1 (by the WBC), but I didn’t really follow the ratings. His name didn’t ring any bells with me. My idea was to defend my title against him and move on to that really big fight I wanted. I wasn’t mentally ready that night. If I had been, beating that Honey guy would have been no problem.”

Curry’s lack of focus in his preparations for the Honeyghan fight was exacerbated by the death of his beloved grandfather. Not only that, but he was embroiled in a managerial dispute with David Gorman, whose contract with Curry was to expire three days after the fight with Honeyghan. But Curry’s choice as his new manager, Akbar Muhammad, wanted Gorman to remain involved as the co-manager, and although Gorman declined to share those duties, he consented to be part of Curry’s corner team.

It was an uncomfortable situation all around, and may have contributed to an undertrained, admittedly distracted Curry needing to lose 11 pounds three days before the fight. Although some sports books had pegged Curry such a prohibitive favorite that they would not post a betting line, one that did accepted a $5,000 wager Honeyghan made on himself at 5-1 odds.

“I’m going to smash his face in,” Honeyghan said of the undisputed welterweight champion who had shown him so little respect.

By the fifth round, a “weak and sluggish” (his words) Curry was running on empty and, late in round six, an accidental head-butt opened a gash over his left eye. Returning to his corner, he advised his handlers that he was through, a message which was agreed to on medical grounds by two ring physicians whose recommendation to halt the proceedings was acted upon by referee Octavio Meyran.

Curry was through, all right, but in ways no one could then have imagined. The “Lone Star Cobra,” a legend in the making and still only 25, would never be quite the same fighter again.

“I had just recently beat, and easy, the top guy in the division (McCrory), so my thinking was, so who is this guy (Honeyghan)?” a reflective Curry said 31-plus years after the fact. “All right, so he was my mandatory. I should have prepared harder for him. But my feeling was that I’d get my mandatory in, no problem, and then go on to something bigger and better. If they had told me more about him, I know I would have been more ready to do what needed to be done.

“Looking back, I blame my management for what happened. But it is what it is. I had to move on, and I have. I’m good with it.”

Well … maybe he’s not all that good with the way things eventually played out. For a time Curry moved on well enough to remind fight fans of what he had been, and might again become. On July 8, 1988, he again claimed a world title when he wrested the WBC super welterweight belt from Gianfranco Rosi on Rosi’s home turf of San Remo, Italy. Rosi went down three times before he quit on his stool after the ninth round.

Curry was back on top, but at it turned out not for long. After a stay-busy fifth-round stoppage of Mike Sacchetti on Jan. 3, 1989, in New Orleans, he journeyed to Grenoble, France, to defend his 154-pound belt against Frenchman Rene Jacquot. But in a virtual replay of the Honeyghan disaster, Curry was listless and ineffective in a unanimous-decision loss. That fight was named The Ring magazine’s Upset of the Year, the second time Curry was on the wrong end of such a shocker, the first being his dethronement by Honeyghan.

This time there would be no redemptive, reputation-restoring comeback. In the three crossroads bouts during the remainder of his career, he was knocked out in 10 rounds by IBF middleweight champion Michael Nunn, in eight rounds by WBC super welterweight ruler Terry Norris and, finally, in seven rounds by Emmett Linton for the vacant and fringe IBA junior middleweight belt.

Curry has been on the IBHOF’s ballot for years, but despite a mostly impressive 34-6 record with 25 victories inside the distance, voters have seemingly determined that his prime was too abbreviated to have a plaque hung alongside those who had more staying power at the elite level. But it can be argued that there are Hall of Famers whose best work never quite approached the periodic masterpieces authored by Donald Curry.

“At the time he beat McCrory I believe he was just as good as Hearns and Leonard,” said Roy Foreman, George’s younger brother and a fellow Texan who believes Curry should receive more credit for however much time he did have as a premier practitioner of the pugilistic arts. “I think he was the absolute best that night.”

Speaking about the times he stubbed his toe against Honeyghan and Jacquot – and against Mike McCallum (to whom he lost twice), Nunn, Norris and Linton, for that matter – is not how Curry wishes to stroll down memory lane. His natural inclination is to keep revisiting his signature performance, when he took apart McCrory as a child might take apart a set of Lincoln logs.

“Knocking out Milton McCrory the way I did should have brought me immediate stardom,” he said. “Milton McCrory was a good fighter, a guy who had the WBC title and was unbeaten. He wasn’t no potato chip fighter. Milton could fight. When you did what I did against Milton McCrory, that’s when management needs to step up. When it doesn’t, it takes away from your spirit as a fighter.”

It is Curry’s contention that the McCrory victory should have vaulted him into a series of megafights that would have continuously fueled his occasionally flagging motivation, the first disappointment coming when he qualified to represent the United States in the 1980 Olympic Games, which the U.S. boycotted in retaliation for the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan. Excuses never play well with any listening audience, and it seems certain Curry will never ascribe any significant blame for his failure to live up to his early rave reviews by looking into a mirror.

As to what he is doing now, Curry (whose older brother, Bruce, was a WBC super lightweight champ who compiled a 34-8 record with 17 KOs) said, “I’m really just relaxing, resting my body, resting my mind. I think I understand boxing better now. I’ve had a lot of time to think about it.”

The emergence of another excellent welterweight from the Dallas Metroplex area, IBF champion Errol Spence Jr., has popularized boxing there again, and has Curry thinking that maybe it’s time to get involved in the sport he walked away from with the intention of never looking back.

“Toward the end of my career my motivation wasn’t really that high,” he said. “I was doing other things rather than just concentrating on boxing. I was ready to get on with the next stage of my life.

“Whenever I go out, I still get recognized, not that I go out that much anymore. I run sometimes at night. It’s not that I’m trying to hide from anything; I’m just trying to get my mind and body back in fighting mode, so if I do go back, maybe as a trainer, I’ll be able to give young fighters what they need to be able to prosper.”

And if Curry ever does get a call from the IBHOF?

“I’d be ecstatic,” he said. “Every fighter would love to be in the Hall of Fame because it would make him feel that he did something special.”

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel.

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Book Review2 weeks ago

Book Review2 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles6 days ago

Featured Articles6 days agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRahaman Ali (1943-2025)

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoTop Rank Boxing is in Limbo, but that Hasn’t Benched Robert Garcia’s Up-and-Comers