Asia & Oceania

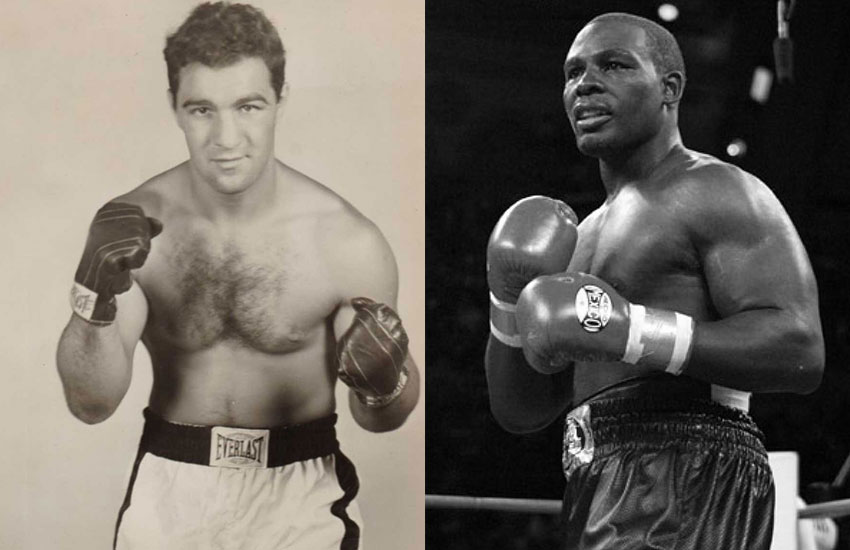

‘Rock’ Rahman and ‘The Rock,’ Marciano, Shared a Common Personality Quirk

In at least one very significant way, two-time former heavyweight champion Hasim “The Rock” Rahman has something in common with his more renowned

In at least one very significant way, two-time former heavyweight champion Hasim “The Rock” Rahman has something in common with his more renowned predecessor upon boxing’s big-man throne, Rocky Marciano. Both held firm to the belief that cash in hand is actual money, but checks, bank drafts and even secured guarantees of future payments for their services constituted something of lesser value. The legend of Marciano is rife with tales of how, after his retirement from the ring, he’d accept speaking engagements for, say, a $10,000 fee and, after his turn at the podium, decline a check in that amount so long as those putting on the event might scrounge up even a fraction of the agreed-upon amount in folding money the “Brockton Blockbuster” could put in his pocket right then and there. And when the famously frugal Marciano died in the crash of a small plane on Aug. 31, 1969, the day before his 46th birthday, an appreciable portion of his fortune could not be located, with those familiar with his ways figuring he had stashed it in secret places known only to a fighter who was as fiercely protective of his legal tender as he was of his undefeated record.

But the obvious link between Rahman, now 45 and retired since 2014, and all-time great Marciano is not nearly as widely cited as that between the onetime street banger and James “Buster” Douglas, another presumably no-hope challenger for boxing’s most prestigious title who journeyed to a distant land and shocked the world by knocking out a seemingly invincible champion. Although the 10th-round KO Douglas – as a 42-1 longshot – scored against Mike Tyson on Feb. 11, 1990, in Tokyo is still regarded as the most shocking upset in boxing history, in retrospect the parallels between that fight and April 21, 2001, when 20-1 underdog Rahman starched Lennox Lewis in the fifth round in Carnival City, South Africa, appear to be increasingly flimsy. Douglas, although larger and probably a better natural athlete than Rahman, was less disciplined and dedicated to his craft; he took down the undertrained and overconfident Tyson in no small part because, for once, he prepared with purpose, dedicating his performance to his recently deceased mother. Lewis might also have incorrectly figured on a paint-by-numbers dismissal of Rahman, but the supposed victim had a powerful punch, better-than-decent skills and a history of showing up ready to give his best effort on most occasions. More than a few knowledgeable observers, familiar with the lackadaisical preparation put in by Lewis, figured that Rahman not only could, but would do what he did when he landed the devastating right hand that for a time turned the boxing world on its collective ear.

It is what happened in the aftermath of the first Lewis-Rahman fight, however, most notably in a covert hotel-room meeting and courts of law, that has resonated more than what took place inside the ropes in South Africa and even later, when the pugilistic principals squared off again in Las Vegas in a fight for so much more than dominion over the heavyweight division. The saga involved a duffel bag full of the kind of currency Marciano and Rahman so loved to hold in their hands, of a key deadline missed, of contractual fine print, of small fortunes that should have been larger ones, and of one man’s underappreciated career that perhaps had a chance to be recognized as something more than a footnote to heavyweight history.

You have to wonder how it all would have turned out had Rahman been less like Marciano, insofar as it concerned money matters, and more like, say, Bernard Hopkins, a product of his city’s (Philadelphia) meaner streets, as was Baltimore’s Rahman, but someone prudent enough to resist the temptation to affix his signature to the bottom of any blank piece of paper no matter how large and cash-stuffed the duffel bag being placed upon a table by crafty promoter Don King.

It is easy now for all the naysayers and tsk-tskers to criticize Rahman, whose purse for the fight immediately preceding his first go at Lewis (for which he was paid a then-career-high $1.5 million) was said to be a paltry $13,000 for his seventh-round stoppage of journeyman Frankie Swindell. But how many of those raised in poverty and accustomed to just scraping by can look at a $500,000 pile of cash, further sweetened with an endorsed check for $4.5 million, and say, “Thanks, but no thanks.” The agreement was finalized at 3 a.m., leaving Rahman’s promoter of record, the now-deceased Cedric Kushner, and HBO officials wondering where their missing guest was during the course of the annual Boxing Writers Association of America Awards Dinner in midtown Manhattan, at which Rahman was to be warmly greeted and the recipient of an HBO offer that would have dwarfed the deal he had just accepted from King.

When Lewis and his representatives successfully sought to have the rematch clause in his contract enforced, judge Miriam Goldman Cedarbaum ruled that Kushner had the right to serve as Rahman’s promoter for the do-over, albeit with part of Rahman’s purse going to Kushner to satisfy legal claims against King and Rahman. Not that Rahman’s end of the reduced deal — $4 million – was chump change, but had he come away from the first fight with Lewis as the free agent he had envisioned himself to be, he would have been the object of a bidding war between HBO and Showtime that might have earned him an additional $70 million to $80 million on a multifight deal, most of which would have been guaranteed money.

When the extremely fit and highly motivated Lewis – who had scuffled with Rahman during a joint appearance on ESPN in which Rahman had derisively hinted that Lewis was gay – exacted his revenge with a fourth-round knockout at the Mandalay Bay, connecting with the same sort of overhand right to the jaw that Rahman had landed on him seven months earlier, it seemed as though Rahman’s giddy time in the spotlight had come to an end. But such a presumption would prove to be at least somewhat premature. “Rock” did have another reign as a world champion, by decree of the WBC after Vitali Klitschko suffered a knee injury and subsequently retired late in 2005. (The elder of the two fighting Klitschko brothers returned to the ring in 2008, regained the WBC title and held it until he retired again, this time for good, in 2012.) Rahman relinquished the strap he had been given without ever having to throw a punch in his first defense, when he was stopped by Oleg Maskaev in the 12th round on Aug. 12, 2005, and he later came up short in title shots against Wladimir Klitschko and Alexander Povetkin, both inside the distance. He called it quits after a three-round unanimous decision loss to fledgling pro Anthony Nansen on June 4, 2014, in Auckland, New Zealand, finishing with a record of 50-9-2 (41) and six KO losses.

It is highly unlikely that Rahman ever will be inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame, but a plausible case can be made that he was the most legitimate of the alphabet American heavyweight champions not named Evander Holyfield from 2001 to 2008, a fallow time for U.S. big men in which the other temporary claimants included the likes of John Ruiz, Chris Byrd, Lamon Brewster and Briggs. You say that future Hall of Famer Roy Jones Jr. held a heavyweight title during the referenced period? True, but RJJ was not a real heavyweight, just a one-and-done visitor to the division who beat the eminently beatable Ruiz and immediately went back down to light heavyweight. Byrd was a slick southpaw who could give anyone fits, but he was actually a bulked-up super middleweight who always seemed like a point guard trying to post up power forwards.

Rahman, on the other hand, could take his man out with a single shot, as evidenced by his turn-out-the-lights drilling of Lewis, and when he put his mind to it, box intelligently and execute fight plans mapped out for him by the more astute members of an assembly line of nine trainers, the better-known of the group being Mack Lewis, Kevin Rooney, Janks Morton, Thell Torrence and Bouie Fisher. He also was quick with a quip, making him popular and accessible to the media, and he had the kind of back story that made for good copy. There was that jagged scar on the right side of his face, a conversation piece that was the result of a 1991 accident in which he was a passenger in a truck whose drunk driver was speeding and ran a stop sign. The driver was killed, but Rahman was thrown clear, only to have his head pinned under the gas tank until help arrived after 20 agonizingly long minutes. Then again, living dangerously was a part of his daily existence in Baltimore, whose inner-city perils were explored in depth during the 1993 to ’99 run of NBC’s gritty series, Homocide: Life on the Street. For a time, he served as muscle for some neighborhood drug dealers. He also survived a shooting in which he was struck by five bullets.

“I felt like I was in a maze with no exit,” Rahman said in 2014. “There were only two ways out, death or the penitentiary.”

But Rahman’s life changed when he was 20 and flattened a former pro boxer in a street fight. The beaten ex-pro directed Rahman to a gym and told him he would make a million dollars in the ring if applied himself with the proper dedication. “He didn’t need to say no more,” Rahman recalled.

Of course, Rahman didn’t make a million dollars, and would not for a long time. But the big break he had been waiting for came when Lewis, who was angling for a megafight with Mike Tyson, decided to fill in some of his down time by accepting a $7 million payday for a stay-busy fight in South Africa against Rahman, who, despite a 35-2 record that included 28 KOs, had been stopped by both Oleg Maskaev and David Tua. Lewis apparently felt so certain of victory that he did not fly into Johannesburg, where the elevation is 5,200 feet above sea level, until just 12 days before the fight. He instead put in most of his moderately exerting training in Vegas, where he had a cameo role in the remake of an old Frank Sinatra heist movie, Ocean’s 11, in which he and Klitschko were to engage in a reel fight instead of a real one. Rahman understood the importance of training at altitude and adjusting to the time change (the fight would take place at 5 a.m. local time, or seven hours later than on U.S. East coast to accommodate the HBO telecast, and he arrived a month in advance.

South African promoter Rodney Berman, who was instrumental in bringing the fight, which was being hyped as “Thunder in Africa,” to Carnival City, said “there is no doubt that (Lewis) will suffer from jet lag when he arrives,” a prediction that proved accurate when a physician who examined Lewis shortly after his plane touched down said the champion was “extremely jet-lagged” and was having difficulty breathing the thin air. And if all that weren’t enough, Lewis came in at a then-career-high 253½ pounds for the weigh-in, another warning sign that he had forgotten the lesson he should have learned on Sept. 24, 1994, when he took Oliver McCall lightly and got starched in the second round in London.

When Rahman dropped the hammer on Lewis in a virtual repeat of the McCall bout, HBO commentator Larry Merchant wryly observed that the dethroned WBC, IBF and lineal titlist “just drowned in Ocean’s 11.”

The unexpected emergence of a unified American heavyweight champion in a division that was increasingly dominated by foreign fighters stamped Rahman as the fight game’s hero du jour in the U.S. He became the subject of two documentaries, the principal in numerous lawsuits, made the rounds of the late-night talk shows and, relishing his first taste of affluence, purchased five luxury cars. HBO was prepared to offer him $14 million for a rematch with Lewis, and Showtime was going to go even higher, $19 million, for a bout with Mike Tyson.

So why did Rahman meet with King in that New York hotel room on the sly and sign for a $5 million title defense against Denmark’s Brian Nielsen, which was to be on the undercard of an Aug. 4, 2001, show in Beijing, China, headlined by WBA ruler Ruiz’s rubber-match defense against Evander Holyfield? Pending a victory over the oafish Nielsen, which was a virtual given, Rahman then was to move on to a bout with the Ruiz-Holyfield III winner for the fully unified championship.

It was a Rubik’s Cube of maybes that quickly fell apart. Nielsen fell out and his slot was filled by David Izon, another kind-of-decent fighter floating along on the periphery of actual contention. He, too, was out of the picture when negotiations to stage the Beijing card collapsed. Ruiz and Holyfield did fight for a third time, on Dec. 15, 2001, with Ruiz retaining his version of the title on a split draw in Mashantucket, Conn. But the biggest impediment to King’s purported plan for Rahman was when the lawsuits began being filed, as they surely had to, with Lewis demanding that his rematch clause be fulfilled and Kushner claiming that his promotional rights to Rahman had been infringed upon.

But questions continued to hang in the air like Los Angeles smog. Why would Rahman, despite his unfamiliarity with the high-finance aspects of boxing, accept pennies on the dollar to go with King when the other options available to him would have brought him so much more money and, were he to beat Lewis again or maybe Tyson, far greater prestige? Maybe it was because he figured that, with Kushner’s deliverance to him of a $75,000 payment before the first Lewis fight but after the contracted deadline, he was at liberty to go in whichever direction he chose. It’s possible he figured that by taking a much easier bout with Nielsen or, later, Izon, he could enjoy the status of being a world champion longer before the harsh reality of a rededicated Lewis or a snarling Tyson set in. And, who knows, perhaps it was simply the sight of that half-million bucks piled on that hotel-room table that made him reach for the pen that made him a bystander to the negotiations instead of the person driving them.

Whatever the reason, Rahman comes off looking the worse for comparison to Douglas, who got knocked out by Holyfield in his first post-Tyson defense but at least had the satisfaction of being paid $23 million. Rahman eventually sued to gain his release from his contract with King, and got it in December 2005, but his new deal with Top Rank did not yield the benefits either side had hoped for. Rahman filed for bankruptcy, citing debts of more than $5 million, including $2.1 million to the Internal Revenue Service.

There is an old saying: a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush. Hasim Rahman mistakenly figured $500,000 in his hand might turn out to be better than $85 million stashed somewhere in that proverbial bush. As financial gambles go, it was a doozy of a miscalculation, but it’s a mistake that has been made before in boxing and will again, human nature being what it is. The gut instinct fighters rely on in plying their brutal trade does not always play out so well when it comes to reading and understanding the fine print.

Here’s hoping the memory of the moment when Rahman’s right hand exploded on Lewis’ chin is enough to salve the disappointment of the duffel bag that did not prove to be quite as full as he once thought. Here’s also hoping that Rahman’s son, 26-year-old heavyweight Hasim Rahman Jr. (4-0, 3 KOs), should he ever give signals that he has the stuff to be a true contender, can avoid the financial pitfalls that have kept his dad from receiving all the rewards he should have reaped from a career mostly well spent.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Book Review4 days ago

Book Review4 days agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoOleksandr Usyk Continues to Amaze; KOs Daniel Dubois in 5 One-Sided Rounds