Canada and USA

27 Years Later, Toney’s Late KO of Nunn Not Such a Shocker

The passage of time has a way of providing perspective to events that once seemed unimaginable. One such event took place on May 10, 1991

The passage of time has a way of providing perspective to events that once seemed unimaginable. One such event took place on May 10, 1991, at a minor league baseball stadium in Davenport, Iowa, when a 20-1 underdog named James Toney, too far behind on the scorecards to have any chance of winning on points, dethroned hometown hero and seemingly invincible IBF middleweight champion Michael Nunn with a bolt-from-the-blue, 11th-round knockout that then seemed almost as big an upset as Buster Douglas over Mike Tyson in Tokyo 15 months earlier.

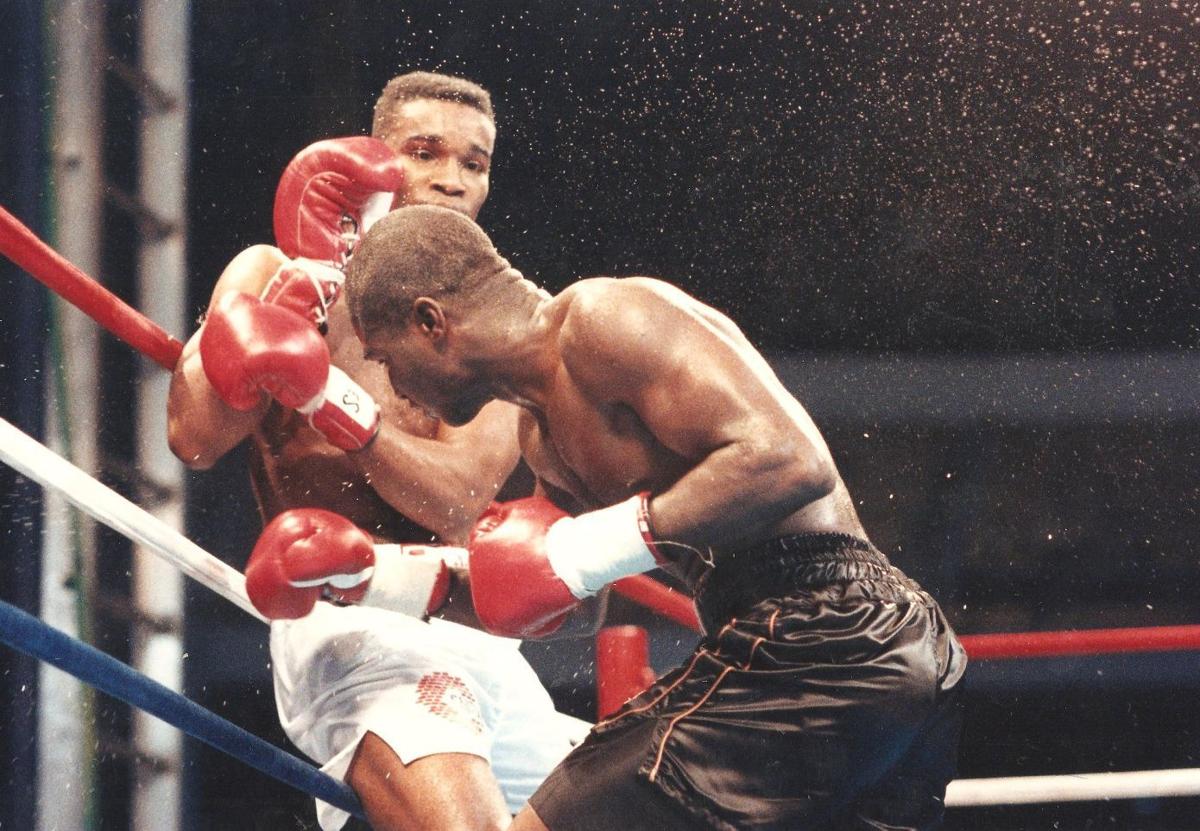

Had Nunn (pictured in the white trunks) played keep-away for another three minutes, 24 seconds, maybe boxing history as currently written would be forever altered for both the winner and the loser of a fight that has largely come to define the divergent careers of both participants. It’s all a matter of conjecture and speculation, of course, but Jackie Kallen, who then managed Toney, has her own ideas of what it meant in real time and for Toney moving forward in a 29-year pro career that may or may not have concluded when he stopped journeyman Mike Sheppard in six rounds in Ypislanti, Mich., on May 13, 2017.

“It made all the difference in the world,” the always fashionable Kallen, who was having her nails professionally done when contacted for this story, said of the left hook that Toney — aptly nicknamed “Lights Out” — landed to instantly darken Nunn’s senses while at the same time putting into place the cornerstone of a highly burnished legacy that should result in Toney becoming a first-ballot inductee into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 2023. The actual induction year could be pushed back until who knows when should Toney decide to keep lacing up the gloves, which is always a possibility for someone who loves to fight even more than he enjoys the carbohydrate-loaded fast food that eventually transformed him from a lean, mean middleweight into a rotund and still-mean heavyweight.

“I expected a decision win for James,” recalled Kallen, which put her in a distinct minority among those in the sellout crowd of 8,000-plus in John O’Donnell Stadium, home of the Class A Quad City River Bandits, and no doubt most viewers of the TVKO telecast, as HBO’s pay-per-view arm was then known. “I thought James would outbox Nunn and win seven or eight rounds, something like that. But through eight I realized he couldn’t win a decision. That’s when it got a little nerve-wracking. But in the ninth and 10th rounds I could see things begin to turn around a little bit, and I knew James had the power to take him out.

“And then that left hook came along, and that was all she wrote.”

The beauty of boxing is that hopelessly lost causes can be reversed with a single bomb of a punch, no matter how late the detonation occurs. Through 10 completed rounds, the 28-year-old Nunn, who was being touted in some quarters as a potential all-time great, was on virtual cruise control, leading by respective margins of 99-91, 98-92 and 97-93 according to the judges’ tabulations. But Nunn, a slick southpaw who tended to carry his hands low and always had been able to get away with it because of his preternatural reflexes, made the mistake of again dipping his right glove. Just 22 but already a veteran of 26 pro bouts, Toney capitalized on the opening by delivering the hook that sent a discombobulated Nunn crashing to the canvas like a load of bricks. Although Nunn staggered to his feet at the count of nine, Toney was like a shark frenzied by blood in the water. He drove Nunn into the ropes, where he landed a right to the chin and another left hook that again put Nunn down. Referee Denny Nelson looked at the stricken and about-to-become former champ, on his hands and knees and with glazed eyes, and dispensed with the formality of a count.

Was it just one of those answered prayers that occasionally turn a signed, sealed and almost-delivered boxing match into a wild scene in the theater of the unexpected? Or was it the sort of transformative moment that can set one fighter on a path to glory and the other on journey into oblivion? Well, maybe in this instance it was a little bit of both.

Nunn recovered from the loss to Toney to become a world champion again two fights later, dethroning WBA super middleweight titlist Victor Cordoba of Panama on a split decision on Sept. 12, 1992. He successfully defended that strap four times before losing to unheralded Philadelphian Steve Little on a split decision on Feb. 26, 1994, in London, an outcome that was much more stunning than was the loss to Toney. Little came into that bout as an absolute no-hoper, with a 22-13-2 record and only five wins inside the distance.

There would be one more bid for a world championship for Nunn, but it also proved to be a disappointment as he dropped a split decision to Graciano Rocchigiani for the vacant WBC light heavyweight crown on March 21, 1998. His final record was 58-4, with 38 KOs and only that solitary flattening by Toney ending in abbreviated fashion. It is a career that upon inspection would seem to be as good or better than those of several fighters who have been inducted into the IBHOF, yet Nunn remains on the outside looking in, his name not even on the ballot, perhaps because he is on the inside looking out, having been convicted of drug trafficking in 2004. Sentenced to 24 years, which would keep him incarcerated until 2028 if maxed out, with time off for good behavior he is now scheduled for release on Dec. 19, 2019.

Is Nunn’s crime against society sufficiently severe to forever bar him from the gate to official immortality in Canastota, N.Y.? It is a question worthy of discussion, given that more than a few Hall of Famers have been guilty of their own moral and legal transgressions, boxing as a whole not being a sport densely populated by choirboys. Which brings us back to Toney (77-10-3, 47 KOs, with no KO losses), who used the watershed conquest of Nunn as a springboard into a boxing life that has since taken on the trappings of legend.

There is, of course, the sort of longevity for which fight fans revere Bernard Hopkins, Archie Moore and George Foreman. But there is also the question of weight, with Toney’s incredible fluctuations – he has fought at poundages as low as 157 and as high as 257 – that put him in a category whose only other members might be Roberto Duran and Manny Pacquiao, similar freaks of nature who persistently demonstrated they could fight and fight well above their supposedly “natural” fighting weights.

“To this day, people come up to me and say, `How much do you weigh?’”, Toney said when asked for what must seem like the millionth time about his addiction to fattening foods. “It’s none of their damn business, and it don’t matter anyway. I could always fight, whatever weight I came in at.”

A star quarterback at Huron High in Ann Arbor, Mich., the 5-10 Toney was then a 205-pounder who said he was offered football scholarships to several colleges, including the University of Michigan. He turned them all down because the idea of kowtowing to screaming coaches was a turn-off to someone whose personality was better suited for individual expression. He preferred to box, anyway.

“I told everybody right from the get-go I wanted to fight as a heavyweight,” Toney said. “Everybody said my body type was too small, that those big guys would knock me out. So my trainer, Stacy McKinley, who I was with then, trained me down to 150. I said OK, but let me tell you, it was killing me. The only way I was able to keep my weight down was to stay in the gym all the time and fight as often as I did.”

Toney was busy, all right, fighting in old-school fashion with 11 bouts in 1989, 10 in 1990 and six in ’91. His most distinctive feature was the rage with which he fought, from those early days right up to his final fight (maybe) against Sheppard. He said whenever he looked at the guy in the other corner, he’d see the face of the abusive father who abandoned him and his mother when he was just seven years old.

“I’m still angry about how me and my mom were treated,” he said. “You never lose that At least I never did. I’d look at my opponents, every one of them, and I’d see my dad. Then I’d try to rip their heads off.”

He came close to ripping Nunn’s head off, but along with the rage he also felt a mounting frustration, saying that for the first five rounds of that fight “it was a damn track meet. All the guy did was slap and run.” And, of course, pile up points.

“They had me as a 20-1 longshot,” Toney continued. “What a slap in the face. I always fight mad, and I did then, but that put an extra-big chip on my shoulder. I wanted to get him out of there so bad. But I think I might have wanted it too bad. I didn’t do what I had trained to do until, like, the sixth round.

“The longer the fight went, I knew I was in trouble. I thought I could still get him out of there, but I was in his hometown. Bill (Miller, Toney’s trainer) kept telling me I was falling more and more behind on points. But I knew that sooner or later I would catch up with him, and then boom! I did.”

Some interesting sidelights on the fight that led, more than anything, to Toney being named Fighter of the Year for 1991 by both the Boxing Writers Association of America and The Ring magazine:

*Nunn’s chief second that night was Angelo Dundee, who famously told his fighter, Sugar Ray Leonard, “You’re blowing it, son! You’re blowing it!” after the 13th round of Leonard’s Sept. 16, 1981, welterweight unification showdown with Thomas Hearns. Leonard promptly went out and stopped Hearns in the 14th round. Well, guess what? Miller, after the 10th round, relayed virtually the same desperate message to Toney, saying, “You’re running out of rounds! You’re going to have to fight him hard the rest of the way!” Bingo.

*Toney grew up in Ann Arbor, but he trained in Detroit, where his manager, Kallen, had served as a publicist for esteemed trainer Emanuel Steward and the top guy in his Kronk Gym stable, Hearns, making for another parallel to the historic first meeting of Leonard and the “Motor City Cobra.”

*Nunn had come up as a pro as the chief attraction for Van Nuys, Calif.-based Ten Goose Boxing, but he had an acrimonious split with the Goossen family, including his one-time trainer, Joe Goossen, who was at ringside as a color commentator for the TVKO telecast. Toney said, prior to the fight with Nunn, several members of the Goossen family came to his hotel room and told him to “kick this guy’s ass for us.”

*Not only did Toney kick Nunn’s ass as requested, but later in his career he was promoted by the now-deceased Dan Goossen, then with Goossen-Tutor Promotions.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Book Review3 days ago

Book Review3 days agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoOleksandr Usyk Continues to Amaze; KOs Daniel Dubois in 5 One-Sided Rounds