Canada and USA

The Once Vibrant Atlantic City Boxing Scene Looks Poised for a Rebound

At least that’s the hope of all those who have vintage Nehru jackets, loud Madras trousers and the lapel-less suit coats once favored by the Beatles stashed in their attics should those trends ever come full circle.

In the world of fashion, it has been said that what was “in” and then “out” eventually becomes “in” again. At least that’s the hope of all those who have vintage Nehru jackets, loud Madras trousers and the lapel-less suit coats once favored by the Beatles stashed in their attics should those trends ever come full circle.

The same might be said of certain cities as destinations for big-time and not-so-big-time boxing. Was it only 1993 that Madison Square Garden Boxing shut down after 110 years, in response to the fight game increasingly having forsaken the “world’s most famous arena” for casino towns such as Las Vegas and Atlantic City? But after a dry spell in part of its own making the Garden is back and again happily splashing in the deep end of the pool, competing for major boxing events with its crosstown rival, the Barclays Center, in an updated version of the 1950s-era Subway Series rivalry involving the lordly New York Yankees and lovably scruffy Brooklyn Dodgers.

In April 2005, Bobby Goodman, the former director of Madison Square Garden Boxing then with Don King Promotions, offered his opinion as to why the Garden’s honchos basically decided to quit on the stool. “There was some bleeding in a financial sense,” he theorized, “and I guess someone decided it would be easier to kill the patient than to come up with a larger Band-Aid.” The big fights, he continued, simply would find a way to “go where the wild goose goes.”

If recent events are any indication, the wild goose is flapping its wings and headed back to Atlantic City, N.J., which is, or soon will be, enjoying the sort of revival that the Big Apple did when the decision-makers at the Garden and new-kid-on-the-block Barclays Center came to the conclusion that New York had too much boxing tradition for the sport of Joe Louis, Sugar Ray Robinson and Muhammad Ali to be put on the curb for collection like yesterday’s trash.

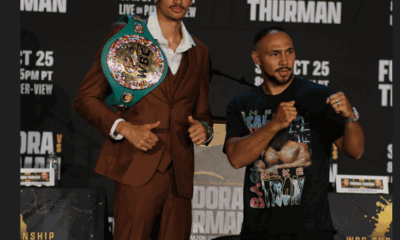

An encouraging sign that Atlantic City’s long-dormant boxing scene was about to be resuscitated came on May 12 in New York when a press conference was held at the Hard Rock Café to announce that the first significant fight card in the Jersey shore resort town in nearly four years would take place on Aug. 4 at the Hard Rock Hotel & Casino, which will officially open on June 28 after a $500 million transformation of the former Trump Taj Mahal. In a nod to the past as well as to the future, the HBO-televised main event will find WBO light heavyweight champion Sergey “Krusher” Kovalev (32-2-1, 28 KOs) defending his title against Eleider “Storm” Alvarez (23-0, 11 KOs). Perhaps not coincidentally, Kovalev appeared in the most recent big fight in Atlantic City, on Nov. 8, 2014, in which the WBO light heavy ruler, in the first of his two reigns, annexed Bernard Hopkins’ WBA and IBF 175-pound belts on a wide unanimous decision.

Kovalev said the matchup with Alvarez is “much more interesting to me now” due to the site, and because Atlantic City has “a special place in my boxing history.”

But the surest sign that Atlantic City will again enjoy a place of prominence in boxing circles came two days later, when the United States Supreme Court voted, 6-3, to strike down the Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act, a 1992 federal law that effectively banned legalized sports gambling in every state other than Nevada. Although the procedures that necessarily must be put into place to make sports betting legal in other gambling-friendly states could take months or even years to enact, then-New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie began a concerted push in 2012 to bring it to his state whenever the Supremes cracked open the gate to a potentially huge revenue stream. Look for Jersey to be at or near the front of the line at whichever point Nevada’s very profitable monopoly comes tumbling down.

Whether or not Bernie Dillon, the Atlantic City Hard Rock’s vice president of entertainment, had advance information that the SCOTUS was going to issue a favorable ruling on the matter before it, is uncertain. But as a long-time advocate of boxing as a means of luring high rollers to the company’s various casino properties, he might have been inclined to proceed in any case.

“Boxing is an important part of our entertainment package,” said Dillon, a former executive with the Caesars and Trump organizations who was there at the dawn of casino gaming in Atlantic City in 1978. “We all grew up on boxing in those days. Jim Allen, who’s the CEO of Hard Rock International, was part of the Trump organization during the heyday of boxing in Atlantic City. He and I remember that period well. We all believe that there can be another revival of the sport there.

“I’ll stop short of calling the boxing part of it a renaissance, but I will say that when the right opportunities come around, we’re going to take a shot at them. Boxing gives us great exposure, it brings in a lot of fans, it creates excitement and electricity. We can put on bigger concerts – we’ve got Maroon 5 coming in, as well as Florida-Georgia Line, Blake Shelton and a lot of others – but there’s nothing like the buzz created the night of a big fight.”

Kathy Duva, CEO of New Jersey-based Main Events, which promotes Kovalev, is as staunch an advocate as Dillon of boxing’s return to Atlantic City on a regular basis. Even when the cupboard was virtually bare on the boardwalk, Jersey girl Duva made the Prudential Center in Newark the de facto home base for one of her company’s headliners, Polish heavyweight contender Tomasz Adamek. But in her heart, the urge to return to her preferred fight destination never abated.

“This is the fun part. The rebirth,” Duva gushed at the New York press conference to formally announce Kovalev-Alvarez, which will be co-promoted in association with Groupe Yvon Michel. “It’s the phoenix rising from the ashes. The city had gone through a period of creative destruction. But the Hard Rock is a big, valuable, established brand. They’re betting on Atlantic City. I’m certainly not going to say they’re wrong.

“This totally feels like I’m going home. It feels so comfortable, so right. And if I’ve learned one thing in boxing, it’s to not ever discount anybody making a comeback. Back when we had a fight scheduled between George Foreman and Evander Holyfield, the gentleman who now runs our country was the host and he told us he wasn’t going to pay the amount he had agreed to and threatened to sue us if we took the fight somewhere else. Mike Marley, who was then with the New York Post, wrote a story and the last line was `No one’s ever going to hear from Donald Trump again.’ So don’t ever count anybody out. Things can happen if you have enough ambition and drive. Clearly, the people who are coming into Atlantic City now have that. Hey, this is Jersey. We don’t ever give up.”

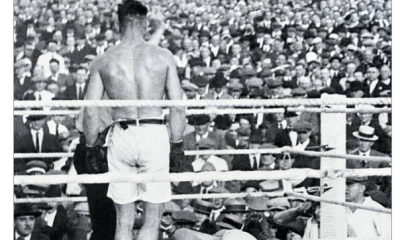

During the halcyon era that began in the late 1970s and continued well into the ’90s, Atlantic City was such a primal force that from 1982 to 1985, it averaged over 130 fight cards a year, with a ridiculous 145 in ’85. It was not unusual during certain weeks for three and even four nationally televised shows to originate there, a smorgasbord of the sweet science that seemed as if it might endure forever at that fevered pitch. Atlantic City, which immodestly billed itself as the “world capital of boxing,” gorged on the sport like a ravenous man at an all-you-can-eat buffet, with the high point of the boom period coming the night of June 27, 1988, when Mike Tyson required only 91 seconds to destroy Michael Spinks in one round of arguably the most anticipated heavyweight bout since Muhammad Ali-Joe Frazier I on March 8, 1971. A live audience of 21,785 packed Boardwalk Hall for Tyson-Spinks, and attendance would have been much higher had the building enough seating capacity to satisfy all ticket requests.

“It was the biggest event in the world at that time – not just in this country or in boxing,” the late Butch Lewis, who managed Spinks, said in 2009. “I’m talking the entire f—— world. If there was a Superdome in Atlantic City, we could have filled that sucker up twice over.”

But the good times stopped rolling, until the runaway train that had been Atlantic City boxing lost so much momentum it all but stopped on the track. There were only five fight cards staged in 2009, the culmination of a deep recession brought about by a variety of factors. The main attraction, Tyson, by and by had lost his zest for combat and took his act on the road; Trump overextended himself with his creditors, and Las Vegas ramped up its game to meet the challenge from the East. Gaming jurisdictions in Connecticut, Pennsylvania, Mississippi, West Virginia and elsewhere began to open, siphoning away some of Atlantic City’s overall and boxing business.

“Atlantic City didn’t fall off the boxing map all at once,” Dillon said in 2009. “The scaling back was kind of gradual.”

While the slippage might have occurred in bits and pieces, there can be no denying that over time it took a heavy toll on the financially strapped municipality. Five of Atlantic City’s 12 casinos closed between 2014 and 2016, and the number of casino workers employed there declined from a high of 49,123 in 1997 to 21,615 as of May 1, 2018. Not surprisingly, casino revenue plunged by nearly half, from $5.2 billion in 2006 to $2.7 billion in 2017.

Ensnared in the throes of that economic downturn, a proponent of what remained of Atlantic City’s fraying boxing ties attempted to gamely soldier on. Jonathan Diego, a former city prosecutor, staged something called the Atlantic City All Star Boxing Gala in 2012, but the venture fizzled after its second annual salute to past glories.

Another bid to re-ignite a bonfire that had been reduced to a few glowing embers was launched in 2017 by Ray McCline, president of the Atlantic City Boxing Hall of Fame, which held its first three-day festival from May 26 to 28 which included an induction class of 24 topped by Tyson, Spinks, Larry Holmes, Dwight Muhammad Qawi, Mike Rossman and posthumous selections Arturo Gatti, Matthew Saad Muhammad and Leavander Johnson.

At the time, McCline insisted he did not want the ACBHOF to be only a celebration of what had been, but of what still might be. “I like to say Atlantic City is recalibrating,” he said. “It’s getting its footing back. Without question, we want to reflect on some of the glory days of Atlantic City boxing, but also to talk about its future. Boxing played a pivotal role in Atlantic City’s best period, and I think it can play a pivotal role again.”

Maybe, just maybe, McCline’s hopeful vision of the future is as feasibly optimistic as those held by Dillon and Duva. Since its 2017 inaugural event – the second such affair is to be staged June 1-3 at the Claridge, whose 25-member induction class includes Evander Holyfield, Bobby Czyz, Jeff Chandler, Vinny Paz, Bruce Seldon, Ray Mercer, Richie Kates and posthumous honoree Hector “Macho” Camacho – AC’s once-faint boxing pulse has gained noticeable strength. Two of the once-shuttered casino hotels have or soon will re-open, with the Hard Rock joined by the Ocean Resort Casino Hotel at what was once the Revel. A third, the Showboat, is operating again as a non-casino hotel.

Also encouraging is the fact that three – count ’em, three! – fight cards will be held during the ACBHOF festivities. Two are set for June 1, one at the Showboat staged by Rising Star Promotions in association with the ACBHOF, the main event of which is a scheduled 10-rounder pitting Philadelphia welterweight Jaron Ennis (19-0, 17 KOs) against Atlantic City’s Mike Arnaoutis (26-10-2, 13 KOs). The other, at the Claridge, staged by Mis Downing Promotions in association with Holyfield and Roy Jones Jr., is topped by the eight-rounder between super middleweight Derrick Webster (25-1, 13 KOs) and Mexico’s Oscar Riojas (16-7-1, 5 KOs).

Boxing returns to Boardwalk Hall – well, to its smaller room, the Adrian Phillips Theater – with a CBS Sports Network-televised 10-round featherweight bout involving Tora Kahn Clary (24-1, 17 KOs), from Providence, R.I., by way of his native Liberia, and Mexico’s Emmanuel Dominguez (22-6-2, 14 KOs), for the fringe NABA title. That show will be a joint collaboration of Holyfield’s The Real Deal Boxing and Mis Downing Promotions.

Those cards, however, are merely appetizers in advance of the Aug. 4 entrée. If Kovalev-Alvarez draws a large and boisterous enough audience, reminiscent of a time when boxing and Atlantic City went together like peanut butter and jelly, it could serve as the impetus to bring more high-visibility fights to a place that has been starving for more filling fisticuff fare.

“It looks good for us,” said Larry Hazzard Sr., the commissioner of the New Jersey State Athletic Control Board who knows what it is like to be there through thick as well as thin. “It’s almost like a perfect storm. Everybody’s efforts have been moving in the same positive direction. It seems as if everyone wants to be a part of what’s coming back around again. A lot of people are getting on the bus.”

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

To comment on this article at The Fight Forum, CLICK HERE.

-

Book Review4 weeks ago

Book Review4 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Debunking Two Myths and Other Notes

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoNikita Tszyu and Australia’s Short-Lived Boxing Renaissance

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoKotari and Urakawa – Two Fatalities on the Same Card in Japan: Boxing’s Darkest Day

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoIs Moses Itauma the Next Mike Tyson?

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoBoxing Odds and Ends: Paul vs ‘Tank,’ Big Trouble for Marselles Brown and More

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 340: MVP in Orlando This Weekend