Canada and USA

Requiem for a Heavyweight: The ‘Fighting Bob’ Martin Story

The boxer — once a promising prospect — is petrified as the world of the prize ring is the only world that he has ever known.

In Rod Serling’s “Requiem for a Heavyweight,” a washed-up boxer is told that he must quit the sport immediately as he risks going blind, or worse, if he has one more hard fight. The boxer — once a promising prospect — is petrified as the world of the prize ring is the only world that he has ever known.

The washed-up boxer Harlan “Mountain” McClintock (played by Jack Palance in the teleplay and Anthony Quinn in the movie version) is a fictional character, but one with hundreds of real-life counterparts. The history of boxing is replete with stories of broken-down fighters with little to show for their exertions struggling to maintain their dignity as they transition into the life of an ex-boxer.

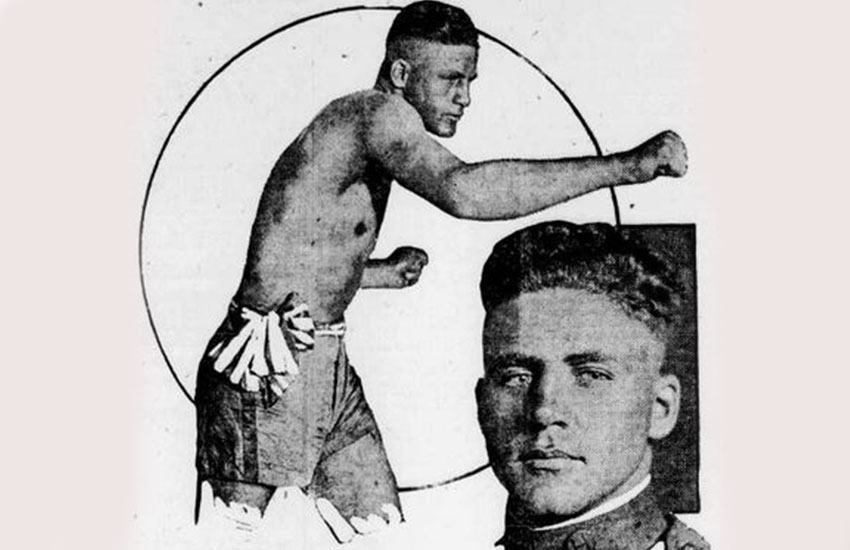

Bob Martin fit the narrative, but his story is yet unique. Few boxers were as exalted when their careers were just taking flight. And Martin flamed out in a hurry. He was all washed-up by his mid-twenties.

Of Scotch-Irish descent with a Cherokee strain, Martin was born on a farm near Clarksburg, West Virginia. In 1917, when the United States joined the war in Europe on the side of the Allies, he was working in a rubber plant in Akron, Ohio. He probably could have gotten a draft deferment had he been so inclined. Rubber was one of the greatest of military necessities and rubber plant workers were integral to the war effort. But Martin wasn’t so inclined. Akron produced more World War I soldiers than any city in Ohio other than Cleveland and Cincinnati, nearly 9,000 soldiers in all, and Bob Martin was one of them.

Boxing was part of the regimen at military camps. In Europe, competitions between regiments were arranged as morale boosters. Martin had engaged in a handful of fights before joining the Army and volunteered to compete at every opportunity. It would be written that Martin scored 66 knockouts in servicemen’s bouts, which is nonsense, but it is a fact that he concussed so many opponents that he became a cult figure. He also picked up a nickname of sorts. He came to be referenced as Fighting Bob Martin, not simply Bob Martin.

The best of the boxers stayed on in Paris for a time after the Armistice was signed to continue their fistic endeavors at pre-arranged tournaments. Fighting Bob had several fights in Paris that would eventually find their way into BoxRec, the sport’s preeminent record-keeper. One of these bouts was a four-round match with Gene Tunney that he lost. Another was a 10-round contest with Fay Keiser to determine the heavyweight champion of the American Expeditionary Forces. The bout went the full distance with Martin winning the decision. He was the bigger man but Keiser, a soldier from Cumberland, Maryland, was vastly more experienced. Back in the states, Fay Keiser had won a newspaper decision over the great Harry Greb in the third of their seven meetings.

BoxRec, although a wonderful treasure trove, indispensable to boxing historians, is, and undoubtedly always will be, a work in progress. Thousands of fights remain buried in the rubble of time awaiting excavation by dogged researchers. Bob Martin’s best win in France is among the missing.

You won’t find it in BoxRec and there was virtually no mention of it in American papers as it rubbed against the transcendent Dempsey-Willard fight in Toledo, but on or about July 4, 1919, Martin knocked out an Australian identified as Captain Cowgill in the very first round (some say the first minute) of the final round of the heavyweight competition at an Inter-Allied tournament at a stadium named for Gen. John J. Pershing in Joinville, France.

That made Fighting Bob Martin the topmost champion of all the conquering armies.

The American troops returned from “Over There” to a grateful nation. More than 150 cities commissioned statues of the doughboy. There’s no evidence that Bob Martin saw combat duty, but he had the patina of a war hero. “Out of the war had come no finer fighting type, no better specimen of physical perfection,” wrote syndicated sportswriter Joe Williams.

The A.E.F. and Inter-Allied tournaments were sponsored by the Knights of Columbus and their point man in France was Jimmy Bronson. A great ambassador for boxing who would be involved in the sport for six decades, Bronson had managed a handful of fighters before the war, most notably Jeff Clark, the Joplin Ghost. He would be waiting at the dock when Martin returned.

Bronson could have had his pick of the litter and in the ensuing years he would be ragged unmercifully for bypassing Gene Tunney in favor of Bob Martin. But hindsight is 20-20 and Bronson would say that it was a no-brainer. Tunney was then a middleweight and his style wasn’t fan-friendly. Martin carried about 190 pounds on his six-foot-two frame, dimensions considered optimal for a heavyweight, and was far more marketable because he had a sledgehammer for a right hand and fight fans were partial to knockout artists.

In his first ring engagement back in the U.S., Martin knocked out two men on the same night. Details are sketchy, but it appears that neither man survived the opening round. The matches were held in conjunction with a county fair in Clarksburg; an auspicious homecoming for the West Virginian. Five weeks later, he met Joe Bonds in Akron in a fight scheduled for 15 rounds. Bonds, a 74-fight veteran, had fought all the good white heavyweights of the era and had once gone 10 rounds with Jack Dempsey. He lasted ten with Martin too, but Fighting Bob took him out in the 11th.

Martin had 12 fights in the next seven months, winning 11. Arthur Pelkey, considered the best Canadian heavyweight, fell in three. Tom McMahon, the Pittsburgh Bearcat, fell in five and never fought again.

Pelkey and McMahon had names that resonated with casual fight fans, but both were tattered remnants of the White Hope era. To raise his stature with hardcore fans, Martin would need to defeat someone like himself; a rising contender. Martin Burke, a New Orleans man, 24 years of age, fit the bill.

Martin vs. Burke, staged on Burke’s turf in New Orleans, was a crossroads fight for both men. Fighting Bob put Burke away in the fifth round and that propelled him on to a bigger stage. On Feb. 18, 1921, he met Bill Brennan at Madison Square Garden. The fight was scheduled for 15 rounds.

Two months earlier, Brennan had given defending heavyweight champion Jack Dempsey a rough go of it for 11 rounds before Dempsey knocked him out in the 12th. ”If Martin can beat Brennan,” wrote a reporter, “he will bounce right into Dempsey’s back yard.” But it was not to be. Fighting Bob had the best of the exchanges through the first five rounds despite bleeding profusely from his mouth, but he faded down the stretch and Brennan won the decision.

Martin rebounded nicely. He was 6-0-1 in his next seven starts including a third round knockout of once-formidable Gunboat Smith and a seventh round knockout of Frank Moran, a two-time world title challenger who had lasted 20 rounds with Jack Johnson.

Martin vs. Moran was staged at an outdoor velodrome in the Bronx before an announced crowd of 20,000 that included Georges Carpentier; the band played “Marseillaise” in his honor. It was a fierce fight, a wild slugfest, and although Fighting Bob scored a clean knockout, he left something of himself in that ring. History would show that he was never the same.

His next fight was a rematch with Fay Keiser, the man he had outpointed to win the A.E.F. title in France. They fought 12 rounds at an armory in Baltimore and Martin received such a severe drubbing that he took the next six months off. During this downtime he had a bad car accident — driving too fast around a curve he wound up in a ditch – and he would come to number this incident as a contributing factor to his downfall as a fighter.

When Martin resumed boxing he took the low road, a conventional tonic calculated to restore his confidence while serving the dual purpose of gilding his record. He hit the tank town circuit where he scored eight fast knockouts over no-name opponents interrupted by a misstep in Akron where he lost a newspaper decision to a fighter of little repute. Then it was time to renew acquaintances with Bill Brennan.

They met on the Fourth of July of 1922 at an amusement park in Ashland, Kentucky. The fight went the full 12 rounds and in contrast to the first meeting it was Martin who had the best of it in the homestretch. But by then he was so far behind that the verdict was a foregone conclusion. Despite the best efforts by the local papers which lathered the event with thick draughts of hype, the promoter took a bath. Rubberneckers watched the fight for free on a hill and on the rooftops of boxcars rather than pay their way into the arena. For them, the fight was less alluring than the fireworks show that would follow it. Fighting Bob was thought to have a large regional following – the amusement park sat across the Ohio River from Huntington, West Virginia – but the turnout bore witness that his following had thinned out.

Fighting Bob Martin had two more noteworthy fights and both ended badly. Very badly.

On Oct. 6, 1922, he was back at Madison Square Garden. In the opposite corner was a strapping 22-year-old lad from out west, Floyd Johnson, who had been lured to New York to serve as a sparring partner for Jack Dempsey. Johnson had come to the fore in the San Francisco Bay Area where he had cleaned up the competition in 4-round fights, the only kind that were then allowed in California.

Fighting Bob was reportedly chalked the favorite. If true, the price-makers could not have been more wrong; he was beaten to a pulp. In the ninth round, the crowd exhorted the referee to stop it, but he let it continue. Finally, in the 10th, Martin’s corner threw in the towel.

When Martin left the ring, said the New York Times, he was a pitiful sight. He had a deep gash over his left eye and the whole left side of his face was swollen. He was taken to a hospital where he was treated for what was described as an internal hemorrhage over the affected eye.

Things have a way of coming full circle in the Queensberry jungle. The young lions build their reps by preying on their elders until the roles are reversed and they become prey for a new generation of young lions. Martin was only 26 years old, but he was old for his years and he should have quit right there. But he didn’t.

Bob had no fear of Martin Burke who he had knocked out in January of 1921, and when Burke proposed a rematch he was all in. What ensued was a sad spectacle. Martin’s offense was non-existent. “His legs trembled, his breath came in short gasps, and he had no capacity for punishment,” wrote an observer. Scheduled for 15 rounds, the bout was halted in the seventh. Bob was still on his feet, but there was no point in continuing.

When Martin fought Bill Brennan in Madison Square Garden, he was accorded a warm ovation when he left the ring, not because his showing was stirring, because it was hardly that, but because he was Bob Martin, a soldier man. When he left the ring in New Orleans after his hollow effort against Martin Burke, he was cursed. “An infuriated mob,” said a report in the Joplin Globe, “hurled ‘Yellow Dog’ and ‘Quitter’ and other such epithets at him.” He was banned from fighting again in New Orleans and the president of the fledgling National Boxing Association sent a letter to all of the major boxing clubs in the country beseeching them to honor the ban “to protect Martin from himself.”

Martin left the sport with a record of 45-12-1 with 42 knockouts. An MP in the Army, he found employment as a West Virginia state trooper but that didn’t last long and then re-enlisted in the Army but that didn’t last long either. When he was mustered out, he spent 64 days at Walter Reid Hospital where physicians diagnosed his neurological deficits as incurable.

In July of 1928, a reporter for a Sandusky, Ohio, paper had a chance encounter with Martin in Huntington, West Virginia. Martin, he informed his readers, had the rolling zig-zag gait of a sailor stepping off the boat after a long sea voyage. He couldn’t perform any activity at a rapid pace without becoming dizzy. Martin was then a father of five, the youngest of whom was only a few months old, and was subsisting on his government disability check. “I can’t find a job,” he told a Charleston Daily Mail sportswriter who wrote under the pen name Cam. “I go to somebody, ask them for a job. ‘Sure’, they say, ‘what’s your name?’ When I tell them ‘Bob Martin’, they find they haven’t anything today.”

If things had been different, if, say, he had been matched more judiciously, would Martin have achieved a lot more as a pro? That’s doubtful. He was slow on his feet, somewhat robotic, and never cultivated a good left hand to complement his money punch. His left, rued Jimmy Bronson, was primarily good for holding his hat. But oh my goodness how he could crack.

In his 1932 book, “A Man Must Fight,” serialized in Colliers magazine, Tunney, the ex-Marine, re-visited their 1919 match at the Salle Wagram in Paris. Martin, he said, hit him with the two hardest punches he ever received, the second of which “felt as though a crossbeam over the ring had snapped and fallen on me.”

When Tunney’s book came out, Bob Martin was 37 years old. The days of his life hadn’t yet reached the midpoint, but from hereon he pretty much falls off the map. Rummaging through old newspapers one searches for information about Bob Martin as a middle-aged and then an old man, but draws only blanks. There’s a note saying that a son is a good high school football player, and that’s about it. One wonders if Bob attended his son’s games and, if so, whether his son would have been embarrassed to see him there.

It remained for Bob Martin to die to become newsworthy once again. He passed away in 1980 in a West Virginia nursing home at age 82. Stubby Currence, a sportswriter for the Bluefield (WV) Daily Telegraph, talked to some of the nurses at the home where he died. The nurses told him that they used to ask Bob who was the heavyweight champion of the world. He would raise both his arms in a victory gesture, and then usually turn over and go to sleep.

Perhaps there’s a special place in heaven for boxers who took punches that never went away, punches with after-shocks, as it were, subtle little after-shocks that over time take a terrible toll. If there is such a place, Muhammad Ali would be there and he would find a kindred soul in Bob Martin. Fighting Bob went off to fight in the war that was ostensibly the war to end all wars; Ali refused to go to war and they were so different in so many other ways. But at the core, they were so very much alike.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

-

Book Review4 weeks ago

Book Review4 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Debunking Two Myths and Other Notes

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoNikita Tszyu and Australia’s Short-Lived Boxing Renaissance

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoKotari and Urakawa – Two Fatalities on the Same Card in Japan: Boxing’s Darkest Day

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoIs Moses Itauma the Next Mike Tyson?

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

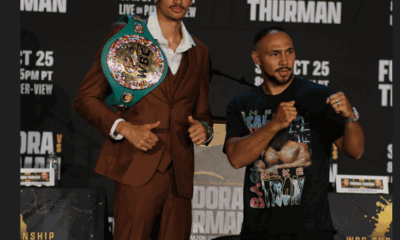

Featured Articles2 weeks agoBoxing Odds and Ends: Paul vs ‘Tank,’ Big Trouble for Marselles Brown and More

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 340: MVP in Orlando This Weekend