Canada and USA

Literary Notes: “Joshua” — Book Review by Thomas Hauser

Given the popularity of boxing in England, we can expect a stream of books about Anthony Joshua from across the pond. Joshua by John Dennen (Yellow Jersey Press) is one of the early arrivals.

Given the popularity of boxing in England, we can expect a stream of books about Anthony Joshua from across the pond. Joshua by John Dennen (Yellow Jersey Press) is one of the early arrivals.

Dennen has had access to Joshua from Anthony’s early days as an amateur. The book is a thorough recounting of AJ’s life in the ring from his first visit to a boxing gym in 2004 through his April 29, 2017, conquest of Wladimir Klitschko.

Joshua was widely hailed after winning a gold medal in the super-heavyweight division at the 2012 London Olympics. Most people forget how close he came to defeat. In the first round, he squeaked by Cuba’s Erislandy Savon by a 17-16 margin. In the gold-medal bout, he was dead even with Roberto Cammarelle of Italy at 18 points apiece and prevailed on the basis of supplemental points. His other two Olympic bouts (against Ivan Dychko of Kazakhstan and Zhang Zhilei of China) were decided by two and four points respectively.

An Olympic gold medal gives a fighter the economic advantage of being fixed in the public consciousness before he turns pro. Cassius Clay (soon to be Muhammad Ali), Joe Frazier, George Foreman, Lennox Lewis, and Wladimir Klitschko all capitalized on their Olympic fame. Super-heavyweight gold-medalists Audley Harrison and Tyrell Biggs met with far less success in the aftermath of their amateur years.

Combining his natural ability and work ethic with the guidance of promoter Eddie Hearn, Joshua has climbed steadily through the professional ranks as a fighter and as a commercial attracton. Dennen takes us on this journey.

There are some evocatively written passages. One that comes to mind is the description of Dominic Breazeale after his seventh-round knockout loss to Joshua.

“Breazeale,” Dennen writes, “was no longer the enemy. He was just a man cutting a forlorn figure as he picked himself off the canvas. A man who had come up against the limits of his ambition. At a time like that, you remembered that his wife and child were in the crowd. You hoped Breazeale had been well paid for what he suffered. You hoped he’d be the same afterwards.”

Dennen has a nice feel for boxing. Among the thoughts he shares are:

* “The boxing ring is a lonely place. In few other areas are limitations of skill and character so painfully and so publicly exposed. In no other sporting endeavor is a small lapse so brutally punished. Miss your attack, drop your guard, and prepare to eat a fist thrown by a man whose business is knowing how to hurt.”

* “In many ways, boxing is a simple morality tale. Nothing comes for free. If you want something, by all means take it. But you can’t take it without the work.”

* “In professional boxing, pain is constant. Boxers suffer. No other sport compares.”

* “You can’t live a normal life and box.”

Dennen’s insights into the essence of boxing are so on the mark that it’s frustrating when he lapses into what seems like hero-worship of his subject. The cover of Joshua proclaims that it’s “the unauthorized biography.” This suggests a warts-and-all exploration. But at times, the book has the feel of a look through rose-colored glasses.

Also, the portrait of Joshua as a person apart from his identity as a fighter is superficial. His relationships with his parents and the other important non-boxing people in his life are given short shrift. So are the years Anthony spent in Nigeria during early childhood.

Similarly, Joshua’s experiences with the criminal justice system in 2009 and 2011 for what AJ later called “fighting and other crazy stuff” are treated in a single paragraph. The “other crazy stuff” (not fully discussed by Dennen) includes an arrest after Anthony was stopped for speeding in North London and the police found eight ounces of cannabis in a sports bag in the car he was driving. Joshua was charged with possession of a controlled drug with intent to distribute, an offense that carried a maximum 14-year sentence. A guilty plea to a lesser charge followed.

Joshua today gives every indication of being a model citizen. But it’s important to acknowledge the valleys he passed through on the way to his current place in society, not just the mountains he has climbed.

At one point, talking generically about boxing, Dennen quotes Charlotte Leslie, a former member of Parliament who once chaired the All Party Parliamentary Group for Boxing.

“What do human beings need to be happy?” Ms. Leslie asked. “They need a sense of identity. Who am I? A sense of purpose. What am I here for? And a sense of community. Who am I with? If kids are not given that through mainstream society, they’ll find that somewhere else. If a gang says, ‘You are for this and you are with us,’ they go there. But that’s exactly what boxing clubs provide. So for the kids who haven’t got any of those things in their lives, the boxing club is there. Boxing clubs provide them with identity, community, and purpose.”

Dennen then writes, “If you have standing within your peer group, you don’t have to do other things to get standing. You don’t have to do criminal stuff, you don’t have to vandalize things, because you have that standing.” But he never applies these thoughts directly to Joshua’s personal journey.

The best writing in the book is a chapter that recounts Dennen’s own abbreviated experience as an amateur boxer.

“I tried boxing myself,” Dennen reminisces. “It was a joyful as well as a hurtful experience. In training, I could haul myself round the Oxford University track where Roger Bannister broke the four-minute mile. I got to try to punch people in the head. I took plenty of blows myself. I bled. I felt the pain. I felt fear. I felt free. I heard the sound, briefly, of a crowd shouting my name. Boxing, for the short time I did it at the low level I did it, let me feel like someone bigger, someone better. Made me feel like I was getting something done. It was a strange kind of magic.”

“The sport may be called amateur boxing,” Dennen continues, “but the name is deceptive. The standard gets very high very quickly. After ten bouts, if you’re not good enough, you can start getting hurt. It’s a dangerous sea if you swim too far out of your depth. I had five bouts in total. Then the coaches advised me to pack it in, to give it up before I came up against someone who knew how to handle themselves and I contrived to get myself hurt. My attempt to box had not been successful, but nevertheless it was a great gift to me.”

“Boxing matters,” Dennen concludes. “It’s dangers can’t be ignored. There is an ugliness to it, in wrong decisions, in the damage, in the bad deals. But there is a beauty to the sport.” And reflecting on the end of his own in-ring experience, he writes, “I could only imagine what it took to make it in boxing, to keep driving yourself into that place. I could imagine it. I couldn’t do it. And it left me in awe of those who could.”

* * *

Madame Bey’s Home to Boxing Legends by Gene Pantalone (Archway Publishing) tells the tale of Hranoush Sidky Bey.

Born in Constantinople circa 1881, Bey came to the United States as the wife of a Turkish diplomat, lived an adventurous life, and, in 1923, opened a training camp for boxers.

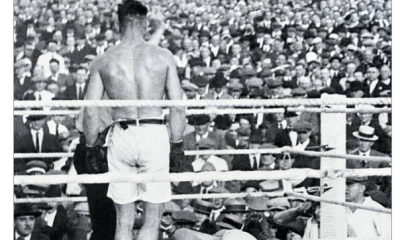

“It was the Madison Square Garden of boxing camps,” Pantalone writes. “No fewer than seventy-eight inductees into the International Boxing Hall of Fame and twelve world heavyweight champions came to the camp in a pastoral town in the deep woods on a mountainside in New Jersey.”

She maintained the camp until her death from a heart attack in 1942.

Pantalone is a great admirer of Madame Bey. He calls her “a pioneer of women in business and sport,” and adds, “She shattered the men-only mentality in the institution of boxing. She understood the physical and mental preparations needed to participate in such battles. Her ability to connect with people without preconceived notions was her greatest strength. She stood tall with the giants of the sport.”

But the book is too long. At times, it seems as though Pantalone is determined to tell readers everything he knows about Madame Bey and anyone who was remotely connected to her. Thus, the book devolves into an endless stream of fighters who trained at, or briefly visited, Bey’s camp. After a while, the sketches blur together.

That said; Madame Bey’s Home to Boxing Legends is exhaustively researched with some interesting biographical material on men like Tex Rickard and Mike Jacobs. And there’s a nice touch when Pantalone writes, “Only the heart of a fighter can carry a battered man to the end.”

Thomas Hauser can be reached by email at thauser@rcn.com. His most recent book – There Will Always Be Boxing– was published by the University of Arkansas Press. In 2004, the Boxing Writers Association of America honored Hauser with the Nat Fleischer Award for career excellence in boxing journalism.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

-

Book Review4 weeks ago

Book Review4 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Debunking Two Myths and Other Notes

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoNikita Tszyu and Australia’s Short-Lived Boxing Renaissance

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoKotari and Urakawa – Two Fatalities on the Same Card in Japan: Boxing’s Darkest Day

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoIs Moses Itauma the Next Mike Tyson?

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRamirez and Cuello Score KOs in Libya; Fonseca Upsets Oumiha

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoBoxing Odds and Ends: Paul vs ‘Tank,’ Big Trouble for Marselles Brown and More