Featured Articles

When Fighting in a Ballpark Really Meant Something

Nowadays, in the technologically advanced age of satellite communications and pay-per-view, live attendance at a boxing match is not nearly as consequential to the bottom line as it once was. Remember when the guaranteed purses of $2.5 million apiece for Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier, for the first of their three epic fights, on March 8, 1971, in Madison Square Garden, was as jaw-dropping as the action in the ring? There were fighters – superb, Hall of Fame fighters — who never came close to grossing that kind of money in their entire careers. The “Fight of the Century” was seen via closed-circuit in 50 countries by 300 million people, which largely contributed to total revenues of nearly $20 million, also numbers that were then record-shattering and considered astounding.

But the sellout, in-house crowd of 20,455, all of whom paid premium prices to be in attendance for Smokin’ Joe’s rousing, 15-round unanimous-decision victory, left the arena with the satisfaction of having experienced something that could not possibly be matched by those watching in a movie theater in, say, Shreveport, Louisiana.

From the giddy heights of Ali-Frazier I, let us flash forward to the most financially profitable boxing event of all time, the much-anticipated, long-delayed pairing of welterweight superstars Floyd Mayweather, Jr. and Manny Pacquiao on May 2, 2015, at the MGM Grand Garden in Las Vegas. Mayweather’s 12-round unanimous decision, a relative exercise in tedium compared to the mega-wattage generated by Ali and Frazier 44 years earlier, was of more interest to readers of Forbes than of The Ring, with 4.6 million pay-per-view buys, $600 million in gross revenues and a live gate of $72,198,500 on a paid attendance of 16,219, according to records furnished by the Nevada State Athletic Commission. For a night’s work, Mayweather came away with roughly $250 million before taxes and Pacquiao with somewhere between $160 million to $180 million.

Recent bouts in soccer stadiums involving WBA, WBO and IBF heavyweight champion Anthony Joshua have served to remind the boxing world that, despite the convenience of someone being able to kick back in his living room to watch a fight on large-screen, high-definition television, there still is nothing quite like the sense of purpose that comes from sharing the moment with tens of thousands of fellow fans. And make no mistake, performing before massive crowds can be as much of an aphrodisiac to a fighter as it is to a rock musician, calling to mind the sad lament of Marlon Brandon’s ex-pug Terry Malloy character in the 1954 Academy Award-winning film, On the Waterfront.

“Remember that night in the Garden you came down to my dressing room and you said, `Kid, this ain’t your night. We’re going for the price on Wilson,’” Malloy tells his mobbed-up brother Charley, played by Rod Steiger. “You remember that? This ain’t your night? My night! I coulda taken Wilson apart! So what happens? He gets the title shot outdoors in a ballpark and what do I get? A one-way ticket to Palooka-ville!”

Outdoors in a ballpark.

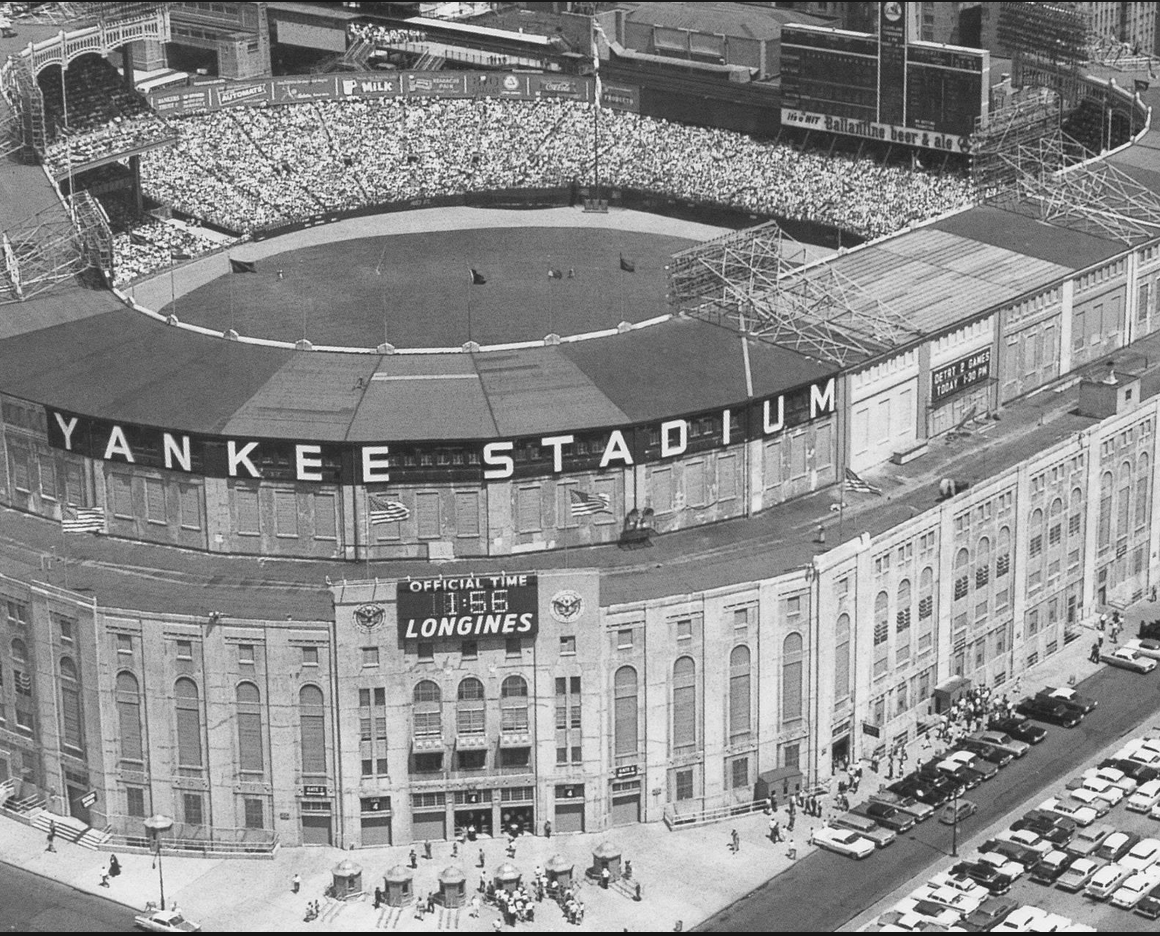

That line calls to mind boxing’s glory days, before television and even to some extent afterward, when the most compelling fights almost necessarily had to be staged in baseball or football venues such as Yankee Stadium, the Polo Grounds, Soldier Field in Chicago and long-gone Sesquicentennial Stadium in Philadelphia. Spectators were like moths drawn to a flame because the mere fact of being there was important to them, even if it required binoculars for those in the cheap seats to see what was taking place down in the ring.

For a fight to be staged “outdoors in a ballpark” – or even indoors, after the advent of domed stadiums or those with retractable roofs – usually required the participation of two elite fighters, or just one, if he was prominent enough or popular enough to draw in the masses on his own. But sometimes there are other factors involved, as was apparently the case on Oct. 20, 1979, when white South African Gerrie Coetzee (then 22-0, 12 knockouts) squared off against black American “Big” John Tate (19-0, 15 KOs), a bronze medalist at the 1976 Montreal Olympics, for the vacant WBA title which had been relinquished by Muhammad Ali.

Apartheid was still the official national policy in South Africa then, which no doubt played as much a factor in a huge – and segregated – crowd of 86,000 packing Loftus Versfeld Stadium in Pretoria, South Africa. Although each fighter was undefeated, Coetzee had never fought outside his home country, with the exception of a one-round stoppage of washed-up former champion Leon Spinks in Monte Carlo, which led to his being paired with Tate. It could be argued that neither man had established himself as a fully legitimate aspirant to a throne only recently vacated by the great Ali. Coetzee’s most significant wins had come against fellow white South Africans Pierre Fourie and Kallie Knoetze, as well as one against former world title challenger Ron Stander, who had been beaten to a pulp by Joe Frazier. Tate’s resume was similarly thin, buoyed somewhat with wins over Knoetze and the overrated Duane Bobick.

What happened throughout the remainder of their careers stamps their confrontation as an outlier in the otherwise significant history of major fights contested before exceptionally large stadium crowds. Although Tate won a 15-round unanimous decision over Coetzee, in his first title defense he was dethroned on a 15th-round knockout by Mike Weaver in a bout Tate was winning handily on points, and even as his promoter, Bob Arum, was negotiating at ringside for him to be matched with Ali in his next outing. It was a fight that never would happen; Tate basically unraveled in finishing with a career mark of 34-3 (23) and weighing a jiggly 281 pounds for his final bout, losing on points to Noel Quarless on March 30, 1988. Even before then, Tate had fallen victim to cocaine addiction and constant scrapes with the law. His boxing earnings gone, he panhandled on the streets of his hometown of Knoxville, Tenn., and reportedly ballooned to over 400 pounds. He was just 43 when he died on April 9, 1998, of a massive stroke.

Coetzee fared somewhat better. He wangled two more shots at a world title; a 13th-round knockout loss to Weaver in Sun City, South Africa, that preceded an upset, 10th round KO of WBA champ Michael Dokes on Sept. 23, 1983, in Richfield, Ohio. Alas, Coetzee would hold onto the title as briefly as Tate had, losing on an eighth-round knockout by Greg Page on Dec. 1, 1984, in Sun City. The “Boksburg Bomber” would retire with a 33-6-1 (21) record.

Clearly, Joshua (22-0, 21 KOs), the WBA/IBF/WBO champion and a super-heavyweight gold medalist for England at the 2012 London Olympics, is a significantly superior talent to Tate and Coetzee, and enough of a national hero in the United Kingdom to fight before 90,000 for his 11th-round stoppage of Wladimir Klitschko on April 29, 2017, in London’s Wembley Stadium. He since has posted victories over Carlos Takam (TKO10) and Joseph Parker (UD12) that each drew more than 78,000 in Wales’ Principality Stadium, and another 80,000 for his seventh-round stoppage of Alexander Povetkin on Sept. 22 in Wembley Stadium. If and when he takes on WBC champ Deontay Wilder, that unification extravaganza likely will take place in Wembley before another capacity-straining throng of 90,000-plus.

Almost single-handedly, Joshua has revived the tradition of fighting “outdoors in a ballpark” (although Principality Stadium has a roof), which largely owes, if not exclusively, to the generational allure of history’s finest heavyweights.

Although the largest live attendances for boxing matches involved non-heavyweights – middleweight champion Tony Zale knocked out Billy Pryor in nine rounds in a free, non-title bout staged by the Pabst Brewing Company before a crowd of 135,000 at Milwaukee’s Juneau Park on Aug. 16, 1941, and WBC super lightweight titlist Julio César Chávez stopped Greg Haugen in five rounds with 132,274 in the stands at Mexico City’s Azteca Stadium on Feb. 20, 1993 – the big boys otherwise rule supreme.

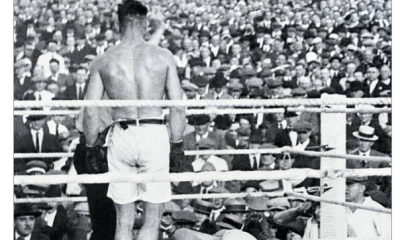

There were 120,757 on hand at Sesquicentennial Stadium on Sept. 23, 1926, to watch Gene Tunney lift the legendary Jack Dempsey’s heavyweight crown on a 10-round unanimous decision. A year less a day later, Tunney retained the title on another 10-round unanimous decision in the famous “Long Count” bout, before 104,943 at Soldier Field.

Dempsey, along with baseball’s Babe Ruth, football’s Red Grange, golf’s Bobby Jones and tennis’ Bill Tilden, was one of the seminal figures in sports’ “Roaring ’20s” golden age. Dempsey drew 91,613 for a fourth-round knockout of George Carpentier in Jersey City, N.J., on July 2, 1921, and 80,000-plus for bouts with Luis Angel Firpo (KO2) at the Polo Grounds on Sept. 14, 1923, and Jack Sharkey (KO7) in Yankee Stadium on July 21, 1927.

Former world champion Max Schmeling kayoed fellow German Walter Neusel in nine rounds before a crowd of 102,000 on Aug. 26, 1934, at Hamburg’s Sandbahn Loksgtedt, a European attendance record for boxing attendance that still stands and may be out of the range of even Anthony Joshua, unless a more spacious stadium than Wembley is constructed. Schmeling was on the wrong end of his one-round beatdown by Joe Louis in their much-anticipated rematch on June 23, 1938, in Yankee Stadium, which drew 70,043 and held the world’s attention to a degree that few if any fights before or since could approach.

Rocky Marciano’s largest live crowd was the 47,585 that showed up on Sept. 21, 1955, for the final fight of his career, a ninth-round knockout of Archie Moore in Yankee Stadium.

Ali, of course, was no stranger to fights that filled stadiums. The largest attendance for any of his ring appearances was the 63,350 that filed into the Louisiana Superdome in New Orleans to see him become a three-time world champion when he avenged an earlier upset loss to Leon Spinks by scoring a 15-round unanimous decision on Sept. 15, 1978. However, of far greater significance to his legacy was his stunning, eighth-round knockout of seemingly invincible champion George Foreman in their “Rumble in the Jungle” fight on Oct. 30, 1974, in Kinshasa, Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo). That fight was seen by “only” 60,000 spectators in Stade du 20 Mai, but in truth the entire world was watching by whatever means were available.

There are drawbacks, of course, to stadium fights, particularly those without a roof. Such fights have been staged in blistering heat, numbing cold, and sometimes pelting rain. It also stands to reason that the larger the crowd, the more difficult it is to later work your way free of the exiting masses in a reasonable amount of time. The trade-off is the sense of community when attending a sold-out event in a massive venue, which contributes to the electricity that one feels emanating from the event itself. That’s the way it is for Super Bowls, World Series and the World Cup, and it’s the way it should be, at least occasionally, in boxing.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

-

Book Review4 weeks ago

Book Review4 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Debunking Two Myths and Other Notes

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoNikita Tszyu and Australia’s Short-Lived Boxing Renaissance

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoKotari and Urakawa – Two Fatalities on the Same Card in Japan: Boxing’s Darkest Day

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoIs Moses Itauma the Next Mike Tyson?

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRamirez and Cuello Score KOs in Libya; Fonseca Upsets Oumiha

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoBoxing Odds and Ends: Paul vs ‘Tank,’ Big Trouble for Marselles Brown and More