Featured Articles

Jonathan Eig’s Biography of Muhammad Ali Distorts Ali’s Post–Exile Fights

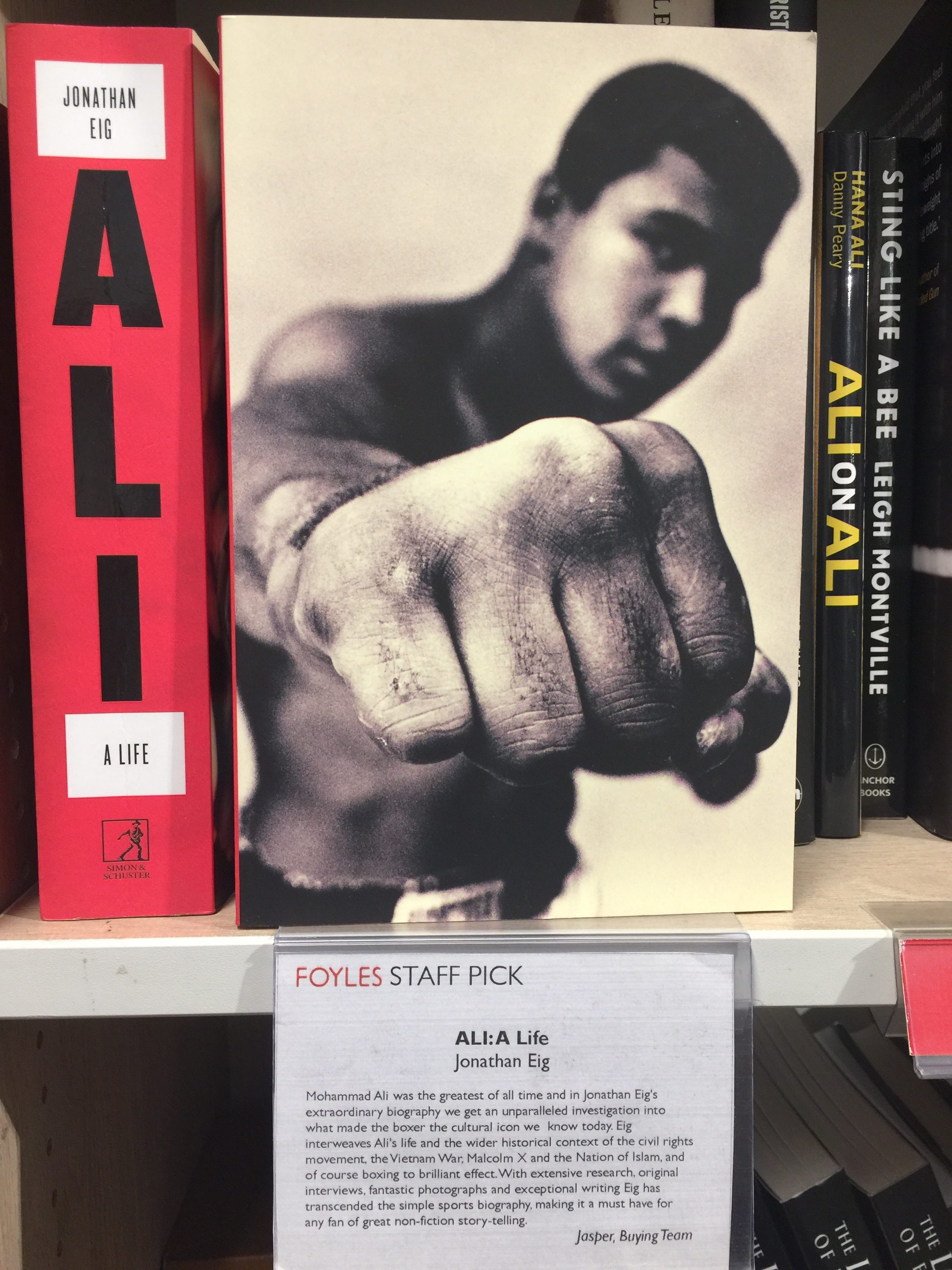

BOOK REVIEW BY SPECIAL CORRESPONDENT MIKE CAHILL — I just finished reading Jonathan Eig’s “Ali: A Life.” Although I enjoyed the first half of the book, after finishing the second half I was greatly troubled. Two things gnawed at me: his view of Ali the man and his opinion of Ali the boxer.

Thomas Hauser in his review of Eig’s book for The Ring addressed both of these deficiencies. “There are times when Eig doesn’t give Ali full credit for his ring skills when he was near his peak,” wrote Hauser. What I would add is that much of what Eig wrote about Ali’s post-exile fights was also off base.

Correcting this matters a great deal because often the last word in biography becomes the standard by which a public figure is judged. If Eig can falsely diminish Ali on his platform – boxing — it makes his social, political, and spiritual legacy easier to diminish, as well. So let’s set the record straight.

The best place to start is with a critique of what evidence Eig chooses to use — and, more importantly, not to use — in judging Ali’s fights. As Hauser noted, Eig is enthralled with CompuBox. Even if one concedes that the CompuBox punch counts are accurate (which they often are not), Eig consistently uses the total number of punches landed as proof of which fighter was superior. But boxing matches aren’t scored by punches landed across the entire spectrum of a fight; they are scored by round. A fighter could conceivably give away a couple rounds (as Ali, maddeningly, sometimes did) and thus get hit more often than his opponent. But if that fighter won eight rounds or more of a 15-round fight, the grand total of punches is irrelevant.

This is obvious to all true fight fans, but what about other readers of Eig’s book, less familiar with the scoring of boxing, who are now left with a false impression?

Let’s examine one group of fights and then five individual fights to make the point.

In 1972 Ali fought six times, winning by KO or TKO four times and twice by one-sided decisions, including his second fight against George Chuvalo that was widely regarded as his best fight since 1967. Ali’s weight was coming down for most of the 1972 fights compared to his 1971 bouts, and he was finding most of his old skills returning, if not his speed.

Eig devotes one paragraph to these fights while later noting that they helped him recover some of his finesse as a boxer. Well, yes — enough that The Ring named him their Fighter of the Year! Yet, in a supreme irony, Eig ends his chapter on this period quoting Bob Foster, who was knocked out in the eighth and was down seven times in all, saying Ali never hurt him.

Ali’s second fight with Joe Frazier in 1974 produced a unanimous decision. The scores of the three officials were 8-4, 7-4-1, and 6-5-1. In addition, the following scorecards are public record:

- Associated Press: 8-4 for Ali

- United Press International: 7-4-1 for Ali

- World Boxing: 6-5-1 for Ali

- International Boxing: 7-4-1 for Ali

Despite this, Eig chooses to tell his readers that Red Smith, who despised Ali, once comparing him to “unwashed punks,” had scored the fight for Frazier. (Who cares?) He then paraphrases Smith who suggested that judges were giving Ali rounds. Eig concludes his section on this fight by saying, “Whether the judges were biased or not,” they named Ali the winner. Here begins a pattern, seen at least three more times, of Eig associating Ali’s wins with biased judges.

Eig also gets mostly wrong his description of the famous 1974 Rumble in the Jungle. He claims Ali’s Rope-a-Dope was “a feat of masochism” and, quoting boxing writer Mike Silver, “a non-strategy.” And he wrote that “Ali lacked the speed to escape and lacked the power and stamina to fight back for more than a fraction of each round.”

He may have lacked speed, but certainly not power, not in this fight. Did Eig see Foreman’s battered face? And no one had more stamina than Ali. In fact, in this fight, the man lacking speed, power, and stamina was George Foreman, not Ali.

Ali’s strategy involved laying against the ropes, yes, but it was brilliant. What Eig misses here is that Ali was not just resting; he was counterpunching like crazy – from the ropes – and then coming off those ropes to pummel Foreman even more. The official cards had Ali comfortably ahead through the completed rounds: 4-2-1, 4-1-2, and 3-0-4.

Boxing author Michael Ezra wrote: “You very well may hear that Ali scored a dramatic victory by backing against the ropes, weathering a brutal battering, and then delivering a sudden knockout. They’d be wrong, though, because what really happened was that Ali whipped Foreman comprehensively from start to finish.” Eig seems only partially to grasp this. At the end of the year, The Ring once again named Ali its Fighter of the Year on the strength of his two strong victories against the two best heavyweights around other than himself. He had won back his title. Reading Eig, you’d never know it.

Now we come to Ali’s 1976 defense against Jimmy Young. In this instance, Eig was correct in that the judges seemed biased for Ali, at least the two that had Ali winning by the scores of 11-4 and 10-3-2. (The third judge also scored it for Ali, but more reasonably at 7-5-3.)

Ali may well have lost that fight; I’m not arguing it either way. Young clearly won the first three rounds and he finished strong. But in the middle rounds, in the eyes of many, Ali had the best of it. “Most ringside writers seemed to agree with the verdict,” wrote Ron Rapoport in the Los Angeles Times. Sports Illustrated’s Mark Kram, noting that Young ducked his head out of the ropes on six occasions, said the decision was correct.

The point is that when Eig states that “everyone but the judges thought Ali had lost,” that simply is not true. A journalist or a historian shouldn’t change facts to fit a narrative.

On page 442 of his book, Eig describes the Ali-Norton rubber match. “Norton was doing most of the punching. He was the busier fighter, the more aggressive fighter, the more artful fighter.” He then claims Ali finished strong in the last minute of the final round.

Ironically, it was actually Norton who opened up in the final 20 seconds of the fight. Eig’s description of Round 15 makes me wonder if he actually watched the round.

If we accept the CompuBox stats of which Eig is so fond (which I do here solely for the sake of argument) they show that Ali landed and threw more punches in Rounds 1, 3, 7, 9, and 13. Norton did so in rounds 2, 5, 6, and 8. Not surprisingly, those rounds were scored unanimously for Ali and Norton respectively, with the exception that one of the supposedly biased judges scored the third round for Norton. In the remaining six rounds, according to CompuBox, Ali threw 404 punches to Norton’s 280, more than 20 more punches per round. CompuBox records Norton as out-landing Ali 108 to 80, a mere 4 punches per round.

Even assuming those numbers are correct, (which is highly doubtful; watch the fight and draw your own conclusion), one can see why Eig — who considers the percentage of punches landed to be the overriding factor in judging a fight — gravitated to those who thought Norton was robbed.

One thing is clear: Ali was busier and more aggressive. In fact, in the last six rounds, Ali out-threw Norton by almost 25 punches per round, while Norton supposedly out-landed Ali by less than three punches per round. I don’t claim Ali definitively won Ali/Norton III (for example AP scored it 9-6 Ali, while UPI had it 8-7 Norton). What I’m arguing is that Eig has ignored the clear evidence that this was a close fight and no one was robbed.

As to the charge that judges in this and other fights were loath to score rounds against Ali, the reality is different. Other than the Young fight, there is no reason to support this theory. At the end of six rounds, the Ali/Norton III fight was scored 5-1, 4-2, and 4-2 in favor of Norton. Had Norton continued to out-box Ali, nothing suggests that the judges wouldn’t have continued to score rounds for him.

It’s important to remember that Ali had by this time already lost decisions to Joe Frazier and Ken Norton. As for the argument that things changed when he became champion, the 1975 Ali-Lyle fight is instructive. Before the fight was stopped in the 11th round, Ali was tied on one scorecard, behind one round on another card and behind 49-43 on another. The 49-43 card gave Ali only one of the 10 completed rounds while scoring two rounds even.

Finally, let’s look at Ali’s 1977 fight with Earnie Shavers. Once again, Eig skews the evidence to support his theory of a fading fighter being carried by the judges. He again writes about percentages of punches landed and thrown, and about how hard Ali was hit in this fight, which he was. But except for acknowledging Ali’s “astonishing” final round, he has nothing positive to say about Ali’s performance. “Once again, perhaps not surprisingly, the judges gave Ali the win,” says Eig.

Where is the evidence? Eleven of the 15 rounds had unanimous scoring, seven of those going to Ali, four to Shavers. In other words, very few rounds were in doubt and the doubtful rounds were split pretty evenly. The official scoring was 9-5-1, 9-6, 9-6. Both wire services, AP and UPI, had it for Ali, respectively 10-5 and 8-6-1. Earnie Shavers himself, in his biography, said Ali was deservedly victorious.

Muhammad Ali won this fight. As Michael Ezra wrote, “In that 15 round struggle, Ali’s ability, confidence, character and intelligence were all on display.”

As mentioned in my opening paragraph, I was also troubled by Eig’s depiction of Ali the man. I was gratified to read Hauser’s comments in his review of Eig’s book that Ali was not only a genuinely nice man, but a spiritual man, perhaps especially in his later, so-called diminishing years. My wife, Cathy, and I have an adult son and daughter who we raised to try to live a spiritual life based on love, service, acceptance of others, learning to rise above adversity, and standing up for what you believe. Although we are Catholic (and white), one of the prime examples of the kind of life worth living that I held up to them was the very imperfect, but yet very beautiful life of Muhammad Ali.

Editor’s note: Author Mike Cahill resides in Chicago.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

To comment on this article in The Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Book Review2 weeks ago

Book Review2 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles6 days ago

Featured Articles6 days agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRahaman Ali (1943-2025)

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoTop Rank Boxing is in Limbo, but that Hasn’t Benched Robert Garcia’s Up-and-Comers