Featured Articles

Rocky Lockridge’s 20-Year Battle With Drugs Was Tougher Than Any 15-Round Fight

“Live fast, die young and leave a good-looking corpse” is a 1950s mantra often, and wrongly, attributed to actor James Dean, star of Rebel Without a Cause and the iconic symbol of the era’s youthful angst. Regardless of the authorship of that fatalistic sentiment, Dean seemingly made it his own during a brief, turbulent life: he was speeding when, at 24, he crashed his car and succumbed to his injuries on Sept. 30, 1955, indeed leaving a good-looking corpse in the casket that was lowered into his grave. More than 63 years later, devotees of all ages continue to mourn the premature passing of the forever-cool Dean, who was spared the reality of growing old gracefully, or at all.

Boxing’s James Dean equivalent was WBC featherweight champion and Mexican national hero Salvador Sanchez (44-1-1, 32 KOs), who was 23 when, driving far too fast, he crashed his land rocket of a car and perished on Aug. 12, 1982. At the time of his death, Sanchez, the perpetually young and fresh embodiment of a magnificent fighter whose career might have been even more celebrated had he lived longer, had a signed contract to fight Rocky Lockridge, another young, exciting and gifted practitioner of the pugilistic arts, in what would have been one of the most-anticipated matchups of the decade.

Perhaps, had he and Sanchez actually squared off, and particularly if Lockridge (44-9, 36 KOs) had come away with a victory that would have surpassed even his signature one-punch knockout of Roger “The Black Mamba” Mayweather, things would have turned out differently for the Tacoma, Wash., native who might also have achieved the legendary status that will forever cloak fans’ cherished memories of Sanchez. But there was an opponent, more insidious than any he ever faced or might have in the ring, that served to strip Rocky Lockridge of his wealth, pride and dignity during a 20-year descent into a nightmarish existence in which he got his ass kicked daily by the twin scourges of drug and alcohol addiction.

Live fast? Die young? Leave a good-looking corpse? None of the outcomes on James Dean’s figurative wish list happened for Lockridge, who, despite his finally being able to kick his drug habit in the last few years of his life, was mostly a broke and broken man when he passed away, at 60, on Feb. 7. At the time of his death, Lockridge – who had suffered a series of strokes that slurred his speech and limited his mobility – was a ward of the State of New Jersey, in hospice care. Despite the no-frills circumstances of his passing, it was nonetheless better than the two decades he spent trapped in the depths of despair. During those lost years the onetime champion was a veritable shadow of his former self, scuffling along on some of the meaner streets of Camden, N.J., and subsisting on whatever he was able to scrounge through charity, panhandling or theft (he was arrested several times for burglary).

“I’ve been down to the pits of hell. I ain’t going back, no way,” Lockridge said in October 2011, after he had gotten himself clean during two very public years as the subject of an A&E reality television show, Intervention, which profiles the struggles of addicts to find sobriety. The ex-champ’s angels of mercy were Jacquie Richardson, executive director of the Retired Boxers Foundation, who put A&E in touch with Lockridge, and Candy Finnigan, the intervention specialist who handled his case for the television program.

But as far as he had fallen, and as disgraced as he felt for having made the poor choices that led to his tumble from grace, there was enough of the personable Lockridge to remind those who cared to remember that there was still a kind and decent human being existing in the hollowed-out shell of what he had become.

“When you’re a kid, everyone has a Superman,” Bobby Toney, who idolized Lockridge when he was on top and befriended him when he was homeless in Camden and most in need of assistance, said in 2009. “I feel like my Superman just went and sat himself down on a big block of kryptonite. He couldn’t get off of it himself. He just needs some people to lift him up.”

Lockridge was a phenom as an amateur, compiling a 210-8 record for the Tacoma Boys Club and winning two national AAU championships and one national Golden Gloves title. Identified as a future professional standout by the Duva family, he and another hot prospect from Tacoma, Johnny Bumphus, came east to New Jersey to be headliners in the early rise of what would become the Main Events promotional dynasty, predating the then-fledgling operation’s signing of 1984 Olympic medalists Evander Holyfield, Pernell Whitaker, Meldrick Taylor, Mark Breland and Tyrell Biggs.

“Rocky was always a low-key person with an easygoing personality,” recalled Kathy Duva, now Main Events’ CEO but then a publicist and wife of the company founder, the now-deceased Dan Duva. “He was quiet, articulate … just a wonderful guy.”

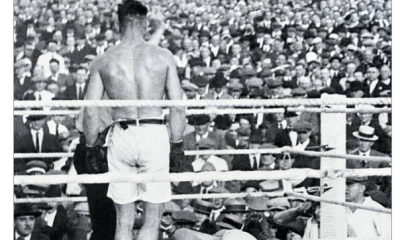

Twice losing bids for the WBA featherweight championship, both defeats coming on points to future Hall of Famer Eusebio Pedroza, Lockridge’s third attempt for a world title proved the charm when he journeyed to Beaumont, Texas, to challenge favored WBA super featherweight ruler Roger Mayweather, who would later gain acclaim as the trainer of his nephew, Floyd Mayweather Jr., on Feb. 26, 1984. Only 25 and 32-3, Lockridge announced himself as not only a star of the moment, but maybe one for years to come, when he required only 91 seconds to starch the “Black Mamba,” the putaway coming on as emphatic a single shot as it ever gets inside the ropes.

“In a stunner, Rocky Lockridge has knocked out Roger Mayweather in round one!” blow-by-blow announcer Marv Albert excitedly informed television viewers.

Many years later, the $3 million fortune he had accrued through boxing long since vanished to his addiction and the sponging of hangers-on who partied with him for however long he could pay for the kind of good times that never last, Lockridge and a friend watched a TV replay of his victory over a Mayweather. It was if Lockridge was reliving a magical moment he wished could have forever been frozen in time.

“You see that man right there, Roger Mayweather?” Lockridge inquired of his guest. “You know who knocked him out? Rocky Lockridge!”

After starching Mayweather, Lockridge retained his title with defenses against Tae Jin Moon and Kamel Bou-Ali before being dethroned on a 15-round majority decision by another future Hall of Famer, Wilfredo Gomez, on May 19, 1985, in San Juan, Puerto Rico. Lockridge reportedly earned a career-high $275,000 for that bout, on whose outcome hinged the kind of fat paydays that would have helped certify him as the great fighter his handlers believed he was on the verge of becoming.

“There are some good purses out there for him,” Lockridge’s manager, Lou Duva, said of what awaited had his guy gotten past Gomez. “All those years are now wrapped up in one night’s battle. Everything is wrapped up in the Gomez fight.”

Not that there wouldn’t be more good times and commendable victories for Lockridge, but already shadows were beginning to shade what should have been a bright and extended run at the top. He received $200,000, his second-highest purse, for an Aug. 3, 1986, shot at WBC super featherweight champ Julio Cesar Chavez, but he came up just short, losing a 12-round majority decision. He rebounded to lift Barry Michael’s IBF super feather belt on an eighth-round stoppage on Aug. 9, 1987, and held it with victories over Johnny De La Rosa and Harold Knight, but lost a 12-round unanimous decision, and his title, to Tony “The Tiger” Lopez on July 23, 1988, in Lopez’s hometown of Sacramento, Calif. That barnburner of a scrap went on to be named Fight of the Year by The Ring magazine. But the exciting setback to Lopez was the beginning of a career-ending downward spiral in which Lockridge lost four of his final five bouts.

When did Lockridge begin to cede portions of his life and talent to the ravages of crack and booze? Even the man himself was uncertain of an exact date, but he knew he was still an active fighter when he began to celebrate victories, or to console himself in defeat, by partying. Fix by fix, drunken stupor by drunken stupor, he lost himself in a befuddled haze that ultimately left him without his wife, who divorced him, and his three sons, one of whom he fathered with a different woman.

“I’m bitter, I’m very bitter,” Lockridge once said of his personal dissolution. “I made some mistakes, a whole lot of mistakes, but they were beyond my imagination. The blow that was put upon me was harder to take than the blows, or any blow, for that matter, that I received in the fight game.”

But there are those, despite Lockridge’s many travails, who believe his career still is worthy of consideration for induction into the International Boxing Hall of Fame. He fought nine current, former or future world champions, almost always holding his own and in more than a few instances prevailing.

George Benton, Lockridge’s trainer and a pretty fair middleweight in his own right who was inducted into the IBHOF, as a trainer, in 2001, always said that the best of Rocky was a marvel to behold.

“He’s beautiful to watch,” said Benton, who was 78 when he passed away on Sept. 19, 2011. “He’s the type of fighter who holds your interest. You know when you go to see him you can’t get up out of your seat to go to the rest room. If you do, it might be all over when you get back.”

The 1980s, and the decade’s alarming legacy of rampant drug use, passed into history nearly 30 years ago. There were fatalities among the world-class athletes and entertainers who did not survive long enough to make it to middle age, and others, like Lockridge, who might have wished for the eternal peace that dying young would have meant. Additional names, like that of Johnny Bumphus, now 58, Lockridge’s Main Events stablemate and a onetime WBA super lightweight champion, are likely to remain on the future casualty list until they aren’t.

“This is as low as I’ve ever been,” Bumphus said in May 1990 of the loss of his sense of self that mirrored his friend and fellow Tacoma native Lockridge. “I’m a drug addict. I’m out of money. I don’t have a job or a house or a car. I had it all and then I smoked it all up, or gave it all away to cocaine.

“I want to apologize to all my fans, all my friends and family, anybody who ever saw me box, anybody I’ve ever known. I made them all proud of me, and now I’ve done this.”

Bernard Fernandez is the retired boxing writer for the Philadelphia Daily News. He is a five-term former president of the Boxing Writers Association of America, an inductee into the Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Atlantic City Boxing Halls of Fame and the recipient of the Nat Fleischer Award for Excellence in Boxing Journalism and the Barney Nagler Award for Long and Meritorious Service to Boxing.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

To comment on this story on The Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Book Review4 weeks ago

Book Review4 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Debunking Two Myths and Other Notes

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoNikita Tszyu and Australia’s Short-Lived Boxing Renaissance

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoKotari and Urakawa – Two Fatalities on the Same Card in Japan: Boxing’s Darkest Day

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoIs Moses Itauma the Next Mike Tyson?

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRamirez and Cuello Score KOs in Libya; Fonseca Upsets Oumiha

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoBoxing Odds and Ends: Paul vs ‘Tank,’ Big Trouble for Marselles Brown and More