Book Review

Robert DeArment’s Book on Bat Masterson Will Delight Boxing History Buffs

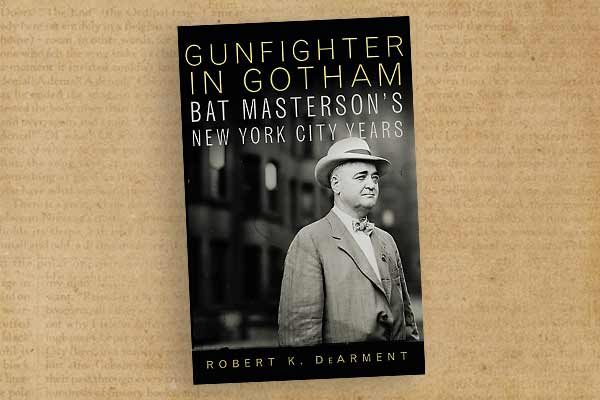

One of the best boxing history books that I have ever read has been around since 2005 and I just stumbled on it. You wouldn’t guess from the title but Robert K. DeArment’s “Broadway Bat: Gunfighter in Gotham” is a book that ought to be on the bookshelf of every serious boxing history buff.

DeArment, a World War II veteran, is recognized as one of America’s leading authorities on life in the Old West, in particular the lives of famous lawmen and outlaws. His 1979 book, “Bat Masterson: The Man and the Legend” (University of Oklahoma Press) is considered one of the best books of the genre.

At various times, Bat Masterson was a County Sheriff and U.S. Marshall in several western hot spots, most famously Dodge City, Kansas, where his legend was born. Dodge City back then, circa 1875, was a wild and wooly town where cattlemen brought their herds and then sowed their wild oats like sailors on shore leave. When Bat said “get out of Dodge,” he did it while pointing his trusty six-shooter at the miscreant.

In truth, however, during his days out west Masterson occupied more of his time as a professional gambler than a peace officer. He ran gambling saloons, invested many hours at faro and poker, and backed other professional gamblers. DeArment’s 1979 book debunked many of the myths about Bat Masterson that were set down in magazine articles and in books aimed at young readers.

Bat Masterson’s life had a second act and the second act could not have been more different than the first. He lived the last 19 years of his life in New York City, spending the first four of those years residing with his wife, a former chorus girl, in a Times Square hotel. He hired on as a sports columnist for The New York Morning Telegraph, rose to the position of sports editor, and had the added duty of handling the accounts of racing tipsters who comprised a good portion of the paper’s advertisers.

The Morning Telegraph, the third oldest daily in New York when it folded in 1972, was part Daily Racing Form, part Variety, part Wall Street Journal, and part scandal sheet. Clergymen denounced the paper from their pulpits which, if anything, was a circulation-booster. Several notable journalists (e.g. Heywood Broun, Louella Parsons) earned theirs spurs at the Morning Telegraph but Masterson never left. He died at his desk in 1921 at age 67.

Masterson cranked out three columns a week that eventually appeared under the heading “Masterson’s Views on Timely Topics.” He had the freedom to write whatever struck his fancy but his forte was boxing, a sport with which he was associated before he arrived in New York. He didn’t like baseball or collegiate sports and had no interest in the new sport of auto racing. As for thoroughbred horse racing, he tended to ignore the subject except during his yearly pilgrimages to Saratoga and Hot Springs. He was particularly fond of Hot Springs, a wide-open town in Arkansas until the reformers clamped down on gambling.

This reporter knew the general particulars of Bat Masterson’s days in New York, but had never seen more than a few snippets of columns he had written. With the help of friends in New York, author DeArment was able to access the full catalog of Masterson’s newspaper stories and present a fuller picture of the man. He was a cantankerous SOB, constantly at war with boxing writers from rival papers and with certain members of the boxing establishment. Fight managers in general, he once wrote, were “a low conniving set of unprincipled cheats.”

A common theme in Bat’s writings was a defense of pugilism. Boxers, he argued, were in less danger than jockeys, professional bicyclists, and football players. But boxing in Masterson’s day was rife with fixed fights and Bat took it upon himself to act as something of an ombudsman for the fans. Exposing the underbelly of boxing was his way of defending the sport which, he wrote, was “a most desirable sport enjoyed by all wholesome and virile men.”

One would have thought that Bat would have supported those empowered to reform the sport, but just the opposite. Masterson, notes DeArment, repeatedly directed his ire at “onerous state laws regulating boxing, the politicians who enacted the laws and the commissioners appointed to administer them.”

This was in character as Masterson detested reformers in general. He viewed the self-appointed guardians of public virtue as mischief-makers who created more problems than they solved. In a column about boxing he might digress to take a swipe at the famous evangelist Billy Sunday or at a well-known feminist stumping for the right to vote. After a convention of suffragettes left Saratoga’s United States Hotel, Bat wrote that the hotel had to be thoroughly fumigated.

Masterson thought the fighters of his day were inferior to their antecedents, an opinion that hardened during the White Hope craze. Although Bat was no fan of Jack Johnson the man, he came to Johnson’s defense when Johnson was found guilty of violating the Mann Act, forcefully expressing the very unpopular opinion that Johnson was railroaded. He came down hard on the New York boxing commission when it banned interracial fights in 1913, likely hastening the fast turnabout; the edict was lifted in 1916. But Bat, like many of his fellow scribes, was guilty of using racial and ethnic epithets in his columns.

Masterson refused to join the Sporting Writers’ Association of Greater New York which was probably a good thing as his presence at its get-togethers would have discomfited a lot of the members. Although he didn’t name names, he was forever using his poison pen to barb boxing writers that took money from promoters and managers in return for favorable write-ups, a practice that was rampant in his day.

Masterson bumped into a lot of these writers, or at least writers that he presumed fit the profile, at the 1919 Dempsey-Willard fight in Toledo where promoter Tex Rickard had set up a free bar at the writers’ hotel. “Some of them got drunk as soon as they hit Toledo and remained in that condition until they left it. And all the time they were sending out their maudlin inventions to the papers they represented.”

Masterson bet big on Willard. For all his knowledge of the Sweet Science, he was a terrible handicapper, going back to the days of John L. Sullivan. He allowed his personal opinion of a fighter’s character to cloud his judgment.

Masterson had no need to take money under the table because he was well-heeled thanks to his friend President Theodore Roosevelt who gifted him with a juicy sinecure shortly after Bat moved to New York, a well-paying post as a federal marshal that didn’t require any work; Bat merely showed up on payday to collect his check. And so, when Masterson attacked corruption, he was a man throwing bricks in a glass house. “While he viciously attacked hypocrites and greedy public servants,” says DeArment, “he himself hypocritically held a no-show, grossly overpaid, taxpayer funded, patronage position for more than four years.”

Masterson’s best friend in New York was Damon Runyon who would immortalize him as the Sky Masterson character in “Guys and Dolls.” Runyon took money from boxing promoter Tex Rickard, but Masterson was fond of both and looked the other way. Likewise, he never railed against the racing tipster industry. As has always been true, those that marketed their product most aggressively were running a scam, but their advertising dollars helped keep his paper afloat.

Masterson was working on his next column when he slumped over his typewriter and died. Just before drawing his final breath, he was inspired to make a snarky observation about social inequality: “The rich and the poor get the same amount of ice in this world. The rich get theirs in the summer and the poor get theirs in the winter.” (In actuality, as DeArment notes, this isn’t word-for-word what Masterson wrote; his cerebration — his most famous line — would be edited to make it punchier.)

Masterson’s protégé, Sam Taub, succeeded him as the Morning Telegraph sports editor. Taub went on to achieve fame as a blow-by-blow man on radio, calling an estimated 1700 fights.

In 1982, the Boxing Writers Association of America created the Sam Taub Award to recognize excellence in boxing journalism. Twelve years later, Taub was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame. Perhaps Bat Masterson will join him there some day.

—

“Broadway Bat: Gunfighter in Gotham,” was released in 2005 by a publishing house in Hawaii that specialized in Western Americana and reissued in 2013 under a slightly different title (as shown in the graphic accompanying this story) by the University of Oklahoma Press. The book, copiously footnoted, has 30 pages of illustrations. It’s a fun read and essential reading for serious students of the sweet science.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

To comment on this article in The Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Book Review4 weeks ago

Book Review4 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Debunking Two Myths and Other Notes

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoNikita Tszyu and Australia’s Short-Lived Boxing Renaissance

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoKotari and Urakawa – Two Fatalities on the Same Card in Japan: Boxing’s Darkest Day

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoIs Moses Itauma the Next Mike Tyson?

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoBoxing Odds and Ends: Paul vs ‘Tank,’ Big Trouble for Marselles Brown and More

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 340: MVP in Orlando This Weekend